Mohan Guruswamy Apr 19, 2019/Commentary

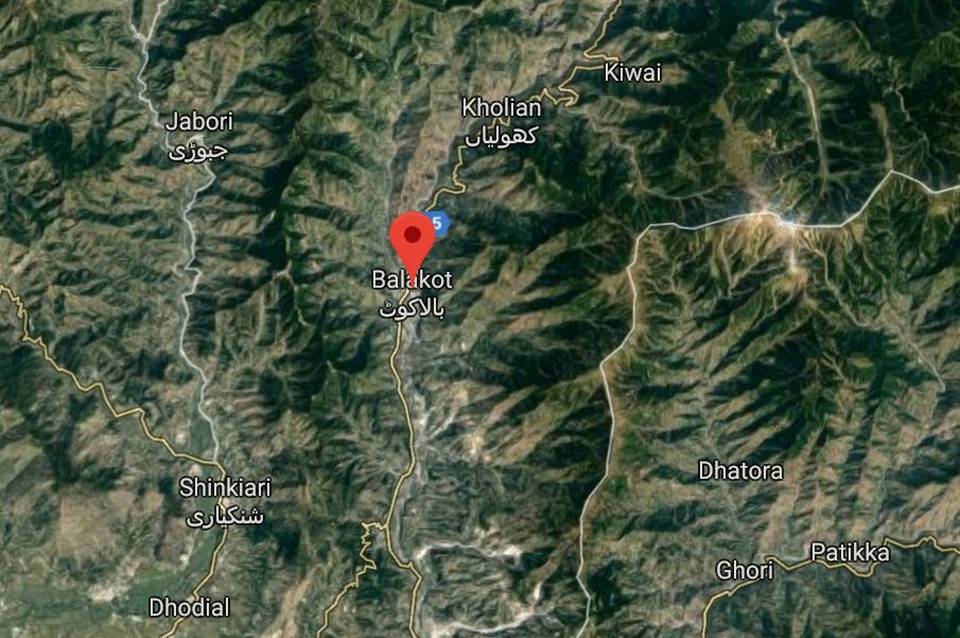

We know that in the aftermath of the Balakot airstrikes, India and Pakistan went into some form of nuclear readiness. The Indian Navy quietly announced last week that all its crucial assets, including the nuclear missile-launching INS Arihant, were deployed in the Arabian Sea. Unlike the United States and the erstwhile Soviet Union (now Russia), which had several stages of nuclear readiness to signal intent and gravity, India and Pakistan have no such signalling language. So, when it comes, it comes.

Politicians on both sides of the border are prone to loose talk and nuclear sabre-rattling is part of their lexicon. But this is not without some reason and purpose. Even though there is little risk of a nuclear world war any longer, because of their awesome power and potential to inflict sudden and massive violence on large populations, nuclear weapons inspire tremendous and often irrational fear, however infinitesimal the probabilities of their use. When both adversaries have nuclear weapons, you have a balance of terror.

As a matter of fact, in the prevailing international situation, any war involving even conventional forces cannot remain a local affair for long, to be sorted out by just the two adversaries. Where there is even the smallest risk of an escalation to nuclear conflict, that intervention could be quite quick. This is what the Pakistanis are counting on.

But since nuclear weapons cannot be used, their only utility lies in the mere threat of their use. In nuclear theology, this has come to be known as “the utility in non-use”. From time to time declared and undeclared nuclear powers have tried to use nuclear weapons in this manner. The Pakistanis are only travelling down a well-trod path. Each time the Pakistanis threaten us with nuclear war, what they are in fact doing is semaphoring to the rest of the world, particularly those of the West, that have taken it upon themselves to supervise the international regime, to intervene.

In the early days of the Yom Kippur war of 1973, an incident occurred which tells a great deal about how the game of nuclear diplomacy is played. The sudden and successful attack by Egyptian troops under the command of Gen. Saaduddin Shazli not only put the Egyptians back on the Sinai Peninsula but also unveiled a new generation of Soviet weapons and tactics to match. At the northern end of Israel, a Syrian armored attack under Gen. Mustafa Tlas was threatening to push the surprised Israelis down the slopes of the Golan Heights. In just the first three days of the conflict, the highly regarded Israeli Air Force lost over 40 fighter aircraft and a huge number of tanks to the new generation of Soviet anti-aircraft and anti-tank missiles. The panicked Israelis turned to the United States for assistance but found Washington quite reluctant. Both President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser Henry Kissinger till then were of the opinion that a degree of battlefield reverses was needed to get an increasingly intransigent Israel to the conference table. Caught, in a manner of speaking, between the devil and the deep sea, the Israelis then played their nuclear card.

American surveillance satellites and high-flying reconnaissance aircraft suddenly began to pick up unusually heightened activity around the Israeli nuclear facility at Dimona near the Negev desert. Israeli defence minister Moshe Dayan, while imploring Dr Kissinger to start the airlift of urgently-needed weapons and military technical assistance, told him about how desperate their situation actually was and had already hinted that Israel might have to resort to nuclear weapons to halt the Arab armies. The alarmed Americans sent a SR-71 Blackbird reconnaissance aircraft fitted with special sensors to detect nuclear material over Dimona. The SR-71’s sensors picked up the signature of nuclear material on a bomb conveyor apparently loading an Israeli fighter-bomber. Whether the nuclear flare registered was from an actual nuclear weapon or radioactive material in a container to simulate a weapon will never be known.

To the advantage of Israel, the Americans read this as preparations for an imminent nuclear attack. Would the Soviets sit quietly when their allies were subjected to a nuclear attack — would have been their immediate thought? Was this going to be the beginning of World War III? Within minutes, President Nixon was on the line to Prime Minister Golda Meir, telling her that a massive US airlift bearing much-needed weapons and military advisers was ordered and that the supply would begin within hours.

In early 1952, as the Chinese poured in troops into Korea to grind to a halt the advance of the American-led UN forces, a highly placed US diplomat in Geneva conveyed through Indian diplomat K.M. Pannikar a warning to China that the United States will use nuclear weapons on it unless it agreed to talks immediately. China soon afterwards agreed to hold talks, which soon resulted in the armistice that holds till today.

Others have done this somewhat differently. During the 1982 Falklands War, the British quietly deployed the nuclear submarine HMS Conqueror, armed with nuclear missiles, off the Argentine coast. As the fighting raged and the Argentines scored some naval victories by sinking the destroyer HMS Sheffield and the converted Harrier jet carrier Atlantic Conveyor, the Royal Navy revealed the presence of its nuclear submarine. The presence of the Conqueror with nuclear weapons was to tell its somewhat lukewarm ally, the United States, that if the war went badly for it Britain would be forced to use even nuclear weapons. It was therefore in America’s interest to not only using its enormous clout with the Argentines to end its occupation of the Falkland Islands but to also assist Britain. Soon after this the US tilted fully in favour of the British by giving it critical intelligence and political support.

In 1992, then US President George H.W. Bush conveyed to Saddam Hussein that a poison gas attack on Israel using its Scud missiles would invite a nuclear strike upon it. The Iraqis fired several Scuds on Israel, but none with poison gas. After the war, UN inspectors scouring Iraq for weapons capable of mass destruction detected huge quantities of poison gas in ready to use explosive triggered canisters. Obviously, the threat had worked.

Clearly, the threat of the first use of nuclear weapons, if provoked beyond a point, could be often as effective as nuclear deterrence. In recent times, to give credence to its irrationality, Pakistan has deployed or claims to have deployed tactical nuclear weapons to some of its formations. Since a tactical nuclear weapon has a much smaller destructive power, its use is considered somewhat more likely and hence more credible than a strategic nuclear weapon. A strategic weapon is a city or area-buster, whereas a tactical weapon is said to have only a battlefield application. But India’s response to this is that whatever the weapon, and wherever it is used, if it is used it will invite a full-scale retaliation. Many analysts think this is not credible, and India needs a flexible policy that will allow it to also match escalation up the ladder.

But the frequent Pakistani outbursts that nuclear war can happen here if the Kashmir situation boils over is an addition to the known nuclear semaphoring practices. Here the Pakistanis are using the Western abhorrence of nuclear war to influence Indian policy. They are not threatening India, because that is not credible, more so since India has a far bigger nuclear arsenal. They are in fact threatening the world that the balance of terror might be breached, and inviting it to intervene. Whatever the nature of this intervention, it is deemed to be in its favour. We saw this happen in 2008 when within minutes of the 26/11 Mumbai attacks Presidents and Prime Ministers from all over began calling our Prime Minister calling for restraint. We have a somewhat ironical situation here. A cruel and ruthless military presiding over a notoriously lawless and corrupt nation is pleading for Kashmir’s supposed right to self-determination and is blackmailing the world to come to its assistance.

The author is a Trustee and Distinguished Fellow of ‘The Peninsula Foundation’. He is a prolific commentator on economic, political, and security issues. The views expressed are his own.

This article was published earlier in Deccan Chronicle.

Photo Credit: PTI