World War I teaches the lesson that a limited conflict can escalate into a nightmare of millions of deaths and unspeakable suffering for which no rational explanation could be found. Military aims and strategies gained priority over meaningful political goals. Although the generals of the German Empire believed that they were relying on Clausewitz’s theory, they actually perverted it. Tactics replaced strategy, strategy replaced politics, politics replaced policy, and policy was militarized.

The same occurred in the interval between the first and second wars in Iraq (1991 and 2003), which have seen a remarkable shift from Clausewitz to Sun Tzu in the discourse about contemporary warfare. Clausewitz enjoyed an undreamed-of renaissance in the USA after the Vietnam War and seemed to have attained the status of master thinker. On War enabled many theorists to recognise the causes of America’s traumatic defeat in Southeast Asia, as well as the conditions for gaining victory in the future. More recently, however, he has very nearly been outlawed. The reason for this change can be found in two separate developments. First of all, there has been an unleashing of war and violence in the ongoing civil wars and massacres, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, in the secessionist wars in the former Yugoslavia, in Syria and Yemen and in the persistence of inter-communal violence along the fringes of Europe’s former empires. These developments seemed to indicate a departure from interstate wars, for which Clausewitz’s theory appeared to be designed, and the advent of a new era of civil wars, non-state wars, and social anarchy. Sun Tzu’s The Art of War seemed to offer a better understanding of these kinds of war, because he lived in an era of never ending civil wars.

The second reason for the change from Clausewitz to Sun Tzu is connected with the ‘Revolution in military affairs’ (RMA). The concepts of Strategic Information Warfare (SIW) and 4th generation warfare have made wide use of Sun Tzu’s thought to explain and illustrate their position. The ‘real father’ of ‘shock and awe’ in the Iraq war of 2003 was Sun Tzu, argued one commentator. Some pundits even claimed triumphantly that Sun Tzu had defeated Clausewitz in this war, because the US army seemed to have conducted the campaign in accordance with principles of Sun Tzu, whereas the Russian advisers of the Iraqi army had relied on Clausewitz and the Russian defence against Napoleon’s army in his Russian campaign of 1812. The triumphant attitude has long been abandoned, since it is now apparent that there is much to be done before a comprehensive approach of the Iraq War will be possible. Yet it seems fair enough to say that, if Sun Tzu’s principles are seen to have been of some importance for the conduct of the war, he must also share responsibility for the problems that have arisen afterwards.

Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, as well as the theoreticians of Strategic Information Warfare, network centric warfare and 4th generation warfare, lack the political dimension with respect to the situation after the war. They concentrate too much on purely military success and undervalue the process of transforming military success into true victory.

And this is exactly the problem. Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, as well as the theoreticians of Strategic Information Warfare, network centric warfare and 4th generation warfare, lack the political dimension with respect to the situation after the war. They concentrate too much on purely military success and undervalue the process of transforming military success into true victory. The three core elements of Sun Tzu’s strategy could not easily be applied in our times: a general attitude to deception of the enemy runs the risk of deceiving one’s own population, which would be problematic for any democracy. An indirect strategy in general would weaken deterrence against an adversary who could act quickly and with determination. Concentration on influencing the will and mind of the enemy may merely enable him to avoid fighting at a disadvantageous time and place, and make it possible for him to choose a better opportunity as long as he is in possession of the necessary means – weapons and armed forces.

One can win battles and even campaigns with Sun Tzu, but it is difficult to win a war by following his principles. The reason for this is that Sun Tzu was never interested in shaping the political conditions, because he lived in an era of seemingly never-ending civil wars. The only imperative for him was to survive while paying the lowest possible price and avoiding fighting, because even a successful battle against one foe might leave one weaker when the moment came to fight the next one. As always in history, if one wishes to highlight the differences to Clausewitz, the similarities between the two approaches are neglected. For example, the approach in Sun Tzu’s chapter about ‘Moving swiftly to overcome Resistance’ would be quite similar to one endorsed by Clausewitz and was practised by Napoleon.

But the main problem is that Sun Tzu is neglecting the strategic perspective of shaping the political-social conditions after the war and their impact ‘by calculation’ on the conduct of war. As mentioned before, this was not a serious matter for Sun Tzu and his contemporaries, but it is one of the most important aspects of warfare of our own times.

Finally, one has to take into account the fact that Sun Tzu’s strategy is presumably successful against adversaries with a very weak order of the armed forces or the related community, such as warlord-systems and dictatorships, which were the usual adversaries in his times. His book is full of cases in which relatively simple actions against the order of the adversary’s army or its community lead to disorder on the side of the adversary, to the point where these are dissolved or lose their will to fight entirely. Such an approach can obviously be successful against adversaries with weak armed forces and a tenuous social base, but they are likely to prove problematic against more firmly situated adversaries.

Clausewitz: a new Interpretation

Nearly all previous interpretations have drawn attention to the importance of Napoleon’s successful campaigns for Clausewitz’s thinking. In contrast, I wish to argue that not only Napoleon’s successes but also the limitations of his strategy, as revealed in Russia and in his final defeat at Waterloo, enabled Clausewitz to develop a general theory of war. Clausewitz’s main problem in his lifelong preoccupation with the analysis of war was that the same principles and strategies that were the decisive foundation of Napoleon’s initial successes proved inadequate in the special situation of the Russian campaign and eventually contributed to his final defeat at Waterloo. Although Clausewitz was an admirer of Napoleon for most of his life, in his final years he recognised the theoretical significance that arose from the different historical outcomes that followed from the application of a consistent, but nevertheless single military strategy. He finally tried desperately to find a resolution that could reconcile the extremes symbolised by Napoleon’s success at Jena and Auerstedt, the limitations of the primacy of force revealed by the Russian campaign, and Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo.

Therefore there can be found four fundamental contrasts between the early and later Clausewitz that need to be emphasised, because they remain central to contemporary debates about his work:

a. The primacy of military force versus the primacy of politics.

b. Existential warfare, or rather warfare related to one’s own identity, which engaged

Clausewitz most strongly in his early years, as against the instrumental view of war that

prevails in his later work.

c. The pursuit of military success through unlimited violence embodying ‘the principle

of destruction’, versus the primacy of limited war and the limitation of violence in war,

which loom increasingly large in Clausewitz’s later years.

d. The primacy of defence as the stronger form of war, versus the promise of decisive

results that was embodied in the seizure of offensive initiative.

Clausewitz’s final approach is condensed in his Trinity, which comes at the end of the first chapter of book I. The Trinity, with all its problems by its own, is the real legacy of Clausewitz and the real beginning of his theory, as he emphasised himself: ‘At any rate, the (…) concept of war [the Trinity, AH-R] which we have formulated casts a first ray of light on the basic structure of theory and enables us to make an initial differentiation and identification of its major components.’

Clausewitz describes the trinity as follows: ‘War is more than a true chameleon that slightly adapts its characteristics to the given case. As a total phenomenon its dominant tendencies always make war a paradoxical Trinity – composed of primordial violence, hatred, and enmity, which are to be regarded as a blind natural force; of the play of chance and probability within which the creative spirit is free to roam; and of its element of subordination, as an instrument of policy, which makes it subject to pure reason.’

The first chapter of On War, and the Trinity as Clausewitz’s result for theory at its end, are an attempt to summarise these quite different war experiences, and to analyse and describe a general theory of war on the basis of Napoleon’s successes, the limitations of his strategy, and his final defeat.

Although Summers referred to Clausewitz’s concept of the Trinity in his very influential book about the war in Vietnam, he falsified Clausewitz’s idea fundamentally.

Clausewitz’s Trinity is quite different from so-called ‘trinitarian war’. This concept is not derived from Clausewitz himself but from the work of Harry G. Summers Jr. Although Summers referred to Clausewitz’s concept of the Trinity in his very influential book about the war in Vietnam, he falsified Clausewitz’s idea fundamentally. Clausewitz explains in his paragraph about the Trinity that the first of its three tendencies mainly concerns the people, the second mainly concerns the commander and his army, and the third mainly concerns the government. On the basis of this ‘mehr’ (mainly), we cannot conclude that ‘trinitarian war’ with its three components of people, army, and government is Clausewitz’s categorical conceptualisation of how the three underlying elements of his Trinity may be embodied.

Since Summers put forward this conception it has been repeated frequently, most influentially by Martin van Creveld. On the contrary, it must be concluded that these three components of ‘trinitarian war’ are only examples of the use of the more fundamental Trinity for Clausewitz. These examples of its use can be applied meaningfully to some historical and political situations, as Summers demonstrated for the case of the war in Vietnam with the unbridgeable gap between the people, the army and the government of the USA. Notwithstanding the possibility of applying these examples of use, there can be no doubt that Clausewitz defined the Trinity differently and in a much broader, less contingent and more conceptual sense.

Looking more closely at his formula, we can see that he describes war as a continuation of politics, but with other means than those that belong to politics itself.

Clausewitz’s concept of the Trinity is explicitly differentiated from his famous formula of war, described as a continuation of policy by other means. Although Clausewitz seems at first glance to repeat his formula in the Trinity, this is here only one of three tendencies which all have to be considered if one does not want to contradict reality immediately, as Clausewitz emphasised. Looking more closely at his formula, we can see that he describes war as a continuation of politics, but with other means than those that belong to politics itself. These two parts of his statement constitute two extremes: war described either as a continuation of politics, or as something that mainly belongs to the military sphere. Clausewitz emphasises that policy uses other, non-political means. This creates an implicit tension, between war’s status as a continuation of policy, and the distinctive nature of its ‘other’ means.

In the present discourse on the new forms of war Clausewitz stands representatively for the “old form” of war. One of the most common criticisms is that Clausewitz’s theory only applies to state-to-state wars. Antulio Echevarria, to the contrary, stated that “Clausewitz’s theory of war will remain valid as long as warlords, drug barons, international terrorists, racial or religious communities will wage war.” In order to harmonize this position with Clausewitz’s very few statements concerning state policy, his concept of politics must be stretched a long way. In this interpretation, it must mean something like the political-social constitution of a community. This interpretation is based on an often-neglected chapter in On War, in which Clausewitz deals with the warfare of the “semi barbarous Tartars, the republics of antiquity, the feudal lords and trading cities of the Middle Ages, 18th Century kings and the rulers and peoples of the 19th Century.” All these communities conducted war “in their own particular way, using different methods and pursuing different aims”. Despite this variability, Clausewitz stresses that war is also in these cases a continuation of their policy by other means.

However, this makes it impossible to express the difference between the policy of states and the values, intentions and aims of the various communities waging war. Therefore, it would make sense to supplement the primacy of politics as a general category by the affiliation of the belligerents to a warring community. If these communities are states, one can speak of politics in the modern sense; if they are racial, religious or other communities, the value systems and goals of these communities (i.e. their “culture”) are the more important factors. Based upon this proposal, we could replace Clausewitz’s meaning of state with the notion of it being that of the intentions, aims or values of the “warring community,” thus remaining much more faithful to his understanding of what a state embodies. Otherwise, we would implicitly express a modern understanding of Clausewitz’s concept of state.

Whereas Sun Tzu was generalising strategic principles for use against weak adversaries, which may lead to success in particular circumstances, Clausewitz developed a wide-ranging political theory of war by reflecting on the success, the limitations, and the failure of Napoleon’s way of waging war.

Taken into account this small change in understanding what Clausewitz was endorsing when speaking of “state policy” his trinity is the starting point for a general theory of war and violent conflict. Whereas Sun Tzu was generalising strategic principles for use against weak adversaries, which may lead to success in particular circumstances, Clausewitz developed a wide-ranging political theory of war by reflecting on the success, the limitations, and the failure of Napoleon’s way of waging war. Although he might have reflected merely a single strategy, he was able by taking into account its successes, limits, and failure to develop a general theory of war, which transcended a purely and historically limited military strategy.

Clausewitz formulates also a crucial reminder. He stressed that, in his Russian campaign, Napoleon Bonaparte—who Clausewitz sarcastically called the “God of War”—won each individual battle of the war. At the end of this war, he was nevertheless the defeated one and had to return to Paris like a beggar, without his destroyed army. Altogether, in almost twenty years of war, Napoleon lost only three large battles—and nevertheless lost everything, since he provoked by the primacy of military success more resistance than his still very large army, the largest which the world at that time had seen, could fight. Despite his military genius, Napoleon was missing a fundamental characteristic: He was not a great statesman. Both qualities collected would have been necessary, in order to arrange from military strength a durable order of peace.

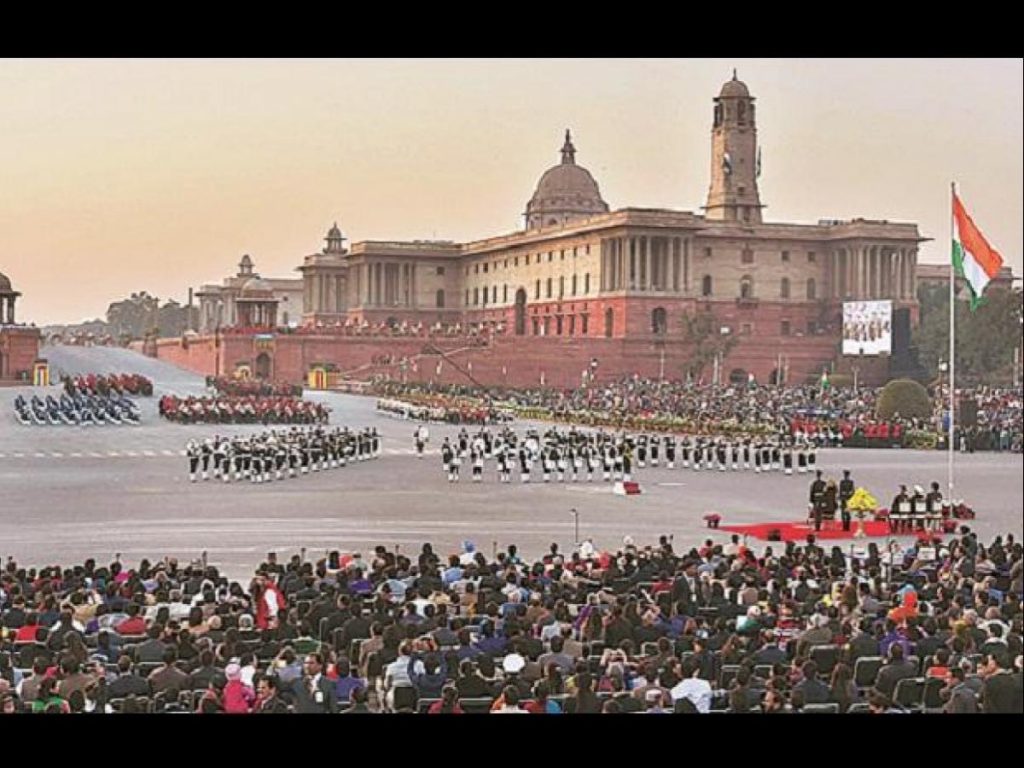

Feature Image Credit: Battle of Jena – Wikimedia Commons

Sun Tzu Image: Sun Tzu – The Art of War

Clausewitz Image: historynewsnetwork.org