The modern world is a product of intense competition and conflict that evolved from the European ‘system of states’ propensity and greed for the acquisition of territory and resources through colonialism and imperialism. The post-1945 world continues to suffer the ills of Western domination and exploitation as is evidenced by the innumerable number of wars, conflicts, and interventions….supposedly part of the imperial civilising missions. As the non-Western world rises the choices are either conflict or cooperation. The G20 Summit 2023 being held in New Delhi is an opportunity to recognise and chart a new path for the world. The authors, Andreas Herberg-Rothe and Key-young Son, emphasise the importance and need for cooperation and harmony amongst the civilisations of the world.

G20 Summit 2023 in New Delhi is underway on September 9-10, 2023.

We propose the non-binary concepts of Clausewitzian floating equilibrium, Confucian harmony, and Arendtian politics of plurality as key ideas to avert and mitigate contemporary conflicts.

In many of the world’s hot spots, both civil and governmental combatants have become embroiled in unending conflicts based on a binary position: “us against the rest.” After two hundred years of imperialism and Euro-American hegemony that have produced varying degrees of adaptation or rejection of Western modernity, it may be time for the world’s great civilizations to learn how to live harmoniously with one another. The world order of the twenty-first century will not be based entirely on modernist ideas and institutions such as nation-states, laissez-faire capitalism, individualism, science and technology, and progress. How then can we accommodate other civilizations and cultures?

We propose mediation, recognition, harmony and floating balance as key principles for inter-civilizational and inter-cultural dialogue and conviviality, accompanied by the awareness that we are all descended from a small group of African ancestors. Mediation and recognition between friends and enemies will be the initial recipes for transforming hostility into partnership, while harmony and floating balance between and within opposites, such as individual versus community, freedom versus equality, will help sustain the momentum for forging constructive relationships.

After the process of political decolonization in the twentieth century, we still need to decolonize our way of thinking. The values of the East and the West cannot survive in their absolute form in this globalized world.

As former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin put it, “You don’t have to make peace with your friends; you have to make peace with your enemies. As a legacy of previous centuries, however, the binary thinking of “us against them” has paradoxically retained a strong presence in twenty-first-century international relations. If this thinking continues to be the decisive force, we could repeat the catastrophes of the twentieth century. After the process of political decolonization in the twentieth century, we still need to decolonize our way of thinking. The values of the East and the West cannot survive in their absolute form in this globalized world. It is our deepest conviction that the Western and like-minded states could only hold on to values such as freedom, equality, emancipation and human rights if they could be harmoniously balanced with the contributions of other civilizations and cultures.

The concept of floating equilibrium, derived from our interpretation of the “wondrous trinity” of the Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz, means not relativity, but relationality and proportionality. At the end of his life, Clausewitz drew the conclusion for the theory of violent conflict that every war is composed of the three opposing tendencies of primordial violence, which he compared to hatred and enmity as a blind natural force, to chance and probability, and to the subordination of war as a political instrument, which makes war subject to pure reason. With Clausewitz’s concept, it is clear that war involves two extreme opposites – primordial violence on the one hand and pure reason on the other. By adding the third tendency, chance and probability, wars become different in their composition.

We use Clausewitz’s concept as a methodological starting point to find a floating balance between various contrasts and contradictions that are evident in the current phase of globalization, which Zygmunt Bauman calls “liquid modernity”. These contrasts include those between the individual and the community, equality and freedom, war and peace, and recognition and disrespect. We argue that Clausewitz’s wondrous trinity and “floating equilibrium” can be used as a way to interpret and mitigate today’s conflicts, although Clausewitz developed these notions to analyze the warfare of his time.

Globalization has led to the “rise of the rest” or Amitav Acharya’s “multiplex world” of nation-states, NGOs, global institutions, global terrorism, and violent gangs of young people from the suburbs of Paris to the slums of Rio who are excluded from the benefits of globalization. This includes both of the following macro developments:

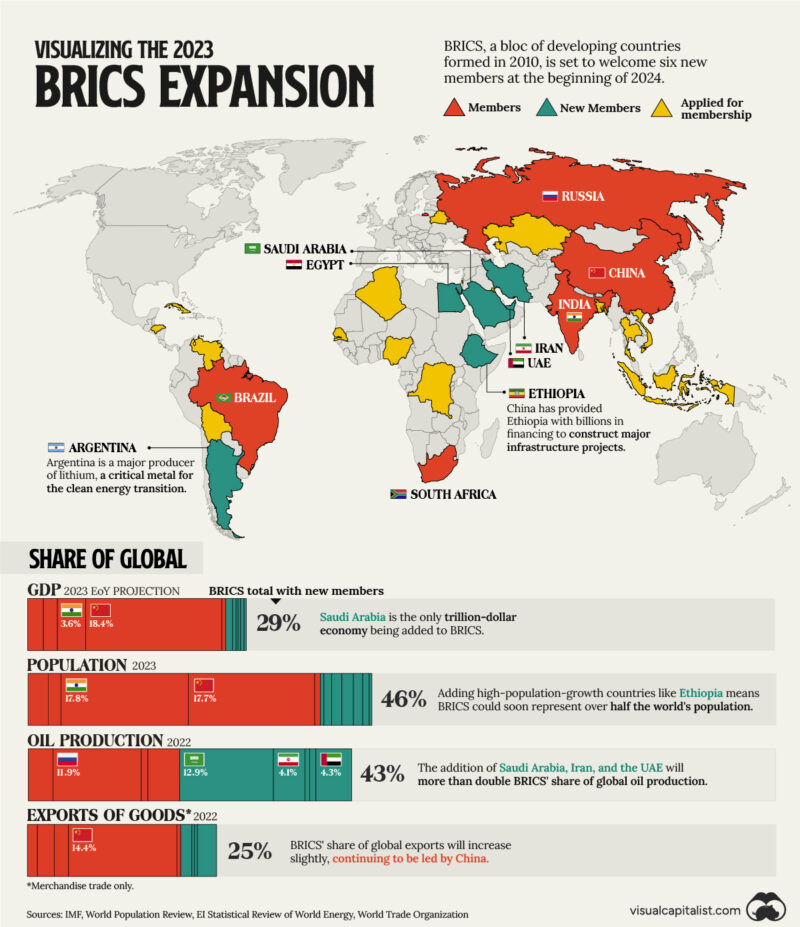

On the one hand, globalization allows the former empires (China, Russia and India) and some developing countries with large populations (Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa) to regain their status as great powers. This development could lead to a global network of megacities competing on connectivity rather than borders, as in China’s efforts to reestablish the ancient trade routes of the Silk Road. On the other hand, it dissolves traditional identities and forms of governance to some extent as a result of social inequality, leading to fragmented societies and a re-ideologization of domestic conflicts, as already seen with the rise of the far right in the US, Europe and Russia, but also Salafism, exaggerated Hindu and Chinese nationalist movements.

the terrible inequalities in this world, where 1% of the world’s population has as much as 99% of the “rest”, or 62 billionaires own as much as 3.5 billion people, are the result of unrestricted and unbalanced freedom. We need to reinvent a balance between freedom and equality so as not to legitimize the inversion of freedom in the name of freedom by the aristocracy of property owners.

Failed states, the wave of migrants and refugees around the world, climate catastrophes, and growing inequalities are the result of the “liquid modernity” that accompanies the dissolution of individual, community, and state identities. Ideologies did not dissolve with the end of the twentieth century or the advent of globalization but rather shifted from modern, utopian ideologies such as socialism and democracy and their aberrations such as Nazism and Stalinism to postmodern ones. The rise of postmodern ideologies such as Salafism is the result of globalization and the West’s refusal to recognize other civilizations and cultures. Moreover, the terrible inequalities in this world, where 1% of the world’s population has as much as 99% of the “rest”, or 62 billionaires own as much as 3.5 billion people, are the result of unrestricted and unbalanced freedom. We need to reinvent a balance between freedom and equality so as not to legitimize the inversion of freedom in the name of freedom by the aristocracy of property owners.

In short, we propose the non-binary concepts of Clausewitzian floating equilibrium, Confucian harmony, and Arendtian politics of plurality as key ideas to avert and mitigate contemporary conflicts. Both Confucian harmony and Hanna Arendt’s concept of plurality are based on the harmonious relationship between different actors, or the floating balance of equality and difference, given that all human beings are similar enough to understand each other, but each is an individual endowed with uniqueness.

Due to the speed and scale of information processing and transmission, the contemporary world is turning much faster than the commonly known modern world. If modernity is a temporal and spatial playground for rationality, the contemporary world is rather a playground for the mixture of the Clausewitzian trinity: reason, emotion, and chance. This means that while we would like to use reason in making decisions, we are often swamped by emotion and ultimately forced to take chances, given the short time frame available for any reasonable calculation and the ever-changing, chameleon-like internal and external environments. As an analyst of war, Clausewitz had long studied this trinity, for war, as a microcosm of human realities, is where reason, emotion, and chance play their respective roles.

In this everyday situation of war, Clausewitz’s revived ideas can offer his posterity many valuable insights. All in all, Clausewitz diverts our attention from the unbalanced diet of the modernists in favour of rationality and offers a healthy recipe for analyzing contemporary problems where reason, emotion, and chance intersect, often with an unexpected outcome.

No matter how powerful a single state may be, it will remain a minority compared to the rest of the world. In this globalized world, there would be no room for any kind of exceptionalism, American or Chinese, but only a floating balance between the world’s great civilizations.

It is a choice between repeating the same mistake of forcibly imposing our own values on the rest of the world, as we did in the twentieth century, or embarking on a new civilizational project of harmony and co-prosperity. No matter how powerful a single state may be, it will remain a minority compared to the rest of the world. In this globalized world, there would be no room for any kind of exceptionalism, American or Chinese, but only a floating balance between the world’s great civilizations. Such a floating balance is a kind of mediation between the opposites of Huntington’s clash of civilizations on the one hand and the generalization of the values of only one civilization on the other. A mere multiplicity of approaches would only lead to a variant of the clash of civilizations. The first step in this direction is to recognize that in a globalized world, great civilizations must learn from each other for their own benefit and interest. If the values of the Western world lead to such terrible and immoral inequalities, we need to rethink our value systems – and if the concept of hierarchy in the Eastern world leads to violations of a harmoniously balanced society, we need to rethink those value systems as well. Whereas in classical Confucianism harmony was based on strict hierarchical oppositions, in a globalized world we need a floating balance between hierarchical and symmetrical social relations, combining Clausewitz and Confucius.

Feature Image Credit: Storming of the Srirangapattinam Fort by the British. Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, 1799. Consolidation of colonialism and imperialism. www.mediastorehoise.com

Mission map for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945. Scale is not consistent due to the curvature of the Earth. Angles and locations are approximate. Kokura was included as the original target for Aug. 9 but weather obscured visibility; Nagasaki was chosen instead. (Mr.98, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Mission map for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945. Scale is not consistent due to the curvature of the Earth. Angles and locations are approximate. Kokura was included as the original target for Aug. 9 but weather obscured visibility; Nagasaki was chosen instead. (Mr.98, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

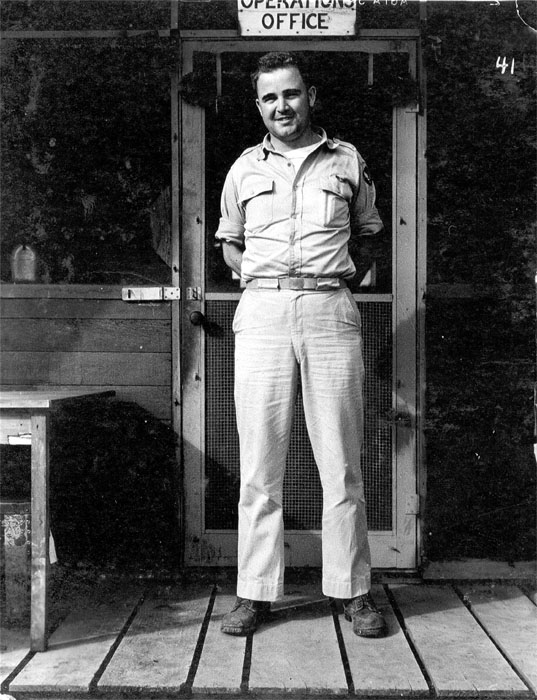

Brigadier General Charles W. Sweeney, pilot of the aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. (Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)

Brigadier General Charles W. Sweeney, pilot of the aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. (Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)