That Israel, in addition to being an apartheid state, has gone completely rogue is no longer in doubt. As Israel digs itself into a deeper hole, in the belief that it can kill its way to success, it finds that this year its GDP has collapsed from 4.8% in 2022 to 1.5%, with over 46000 small businesses having shut down. By some estimates, between 500,000 to 1 million Israelis have permanently emigrated.

Approximately 7 million Jewish Israelis and an equal number of Palestinians live cheek-by-jowl between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. The area encompasses Israel, the occupied territories of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. Nominally, the Palestinians in the West Bank do have limited self-rule, but defacto have no control over the movement of people and goods, or taxes. Agreements signed in the 1990’s, permit the Israeli Government to collect taxes on behalf of the Palestinian Authority (PA), which it then disburses to the PA for its use. These taxes make up over 65-70% of the PA’s public budget and have a critical impact on the quality of life of ordinary Palestinians.

As has been the norm with Israel, it has used every means, including financial control, to inflict collective punishment on the Palestinians at any attempt by them to free themselves from Israeli occupation. In May this year, for example, it withheld disbursal of all taxes collected over the past three months on grounds that Spain, Ireland and Norway had announced they would recognise the Palestinian State. This resulted in the breakdown of municipal services and widespread loss of jobs. Subsequently, in June it indulged in blatant blackmail when it agreed to disburse withheld funds, provided the PA retroactively approved five settlements in the West Bank that had been illegally established earlier, despite condemnation by Palestinians and the international community.

While the Hamas attack of 7 October 2023, especially their despicable actions against women, children and civilians, has been widely condemned, the fact that over half of the 1200 Israelis killed, were by their own military in pursuant of the reprehensible “Hannibal Directive”, continues to be glossed over. Oddly enough, over the course of that year, prior to the attack, the fact that over 200 Palestinians had been killed by the Israeli military and settlers for a variety of reasons has simply been ignored by the international media and not been seen as the immediate provocation for the attack, especially its ferocity.

It now emerges, that the numbers of Palestinians killed by the Israeli response has been grossly underestimated. As per a study dated 10 July 2024 in the Lancet, a respectable and authoritative medical journal, an estimated 186000-200,000 Palestinians have been killed in Gaza, directly or indirectly. This is approximately 9% of the total population, the overwhelming majority of them being women and children.

The Israeli response to this attack was disproportionate, to put it mildly, but it still continues to receive full support from Western Governments. It now emerges, that the numbers of Palestinians killed by the Israeli response has been grossly underestimated. As per a study dated 10 July 2024 in the Lancet, a respectable and authoritative medical journal, an estimated 186000-200,000 Palestinians have been killed in Gaza, directly or indirectly. This is approximately 9% of the total population, the overwhelming majority of them being women and children.

The difference between these estimates and the official figures released by the Gaza Health Ministry, which presently stands at approximately 43000, is explained by the fact that the Ministry only accounts for bodies that have been found and not for those remaining under the rubble, that the cities have been reduced to. Nor does it account for the indirect deaths due to hunger, non-availability of medical help etc. Studies suggest that these tend to be between 5-10 times higher than the official figures.

Israel’s inhuman and deliberate response has been decried by experts, governments, United Nations Agencies and NGOs. They have gone on to accuse Israel of carrying out a genocide against the Palestinian population in Gaza, and more recently, in the West Bank. What is even more horrific, if that is even possible, are the accusations made by Dr. Feroze Sidhwa, an American trauma surgeon, on his return from Gaza. In his devastating op-ed in The New York Times, titled “65 Doctors, Nurses and Paramedics: What We Saw in Gaza”, he recounts harrowing stories from dozens of healthcare workers and CT scans of children shot in the head or the left side of the chest. The Times called the corresponding images of the patients too graphic to publish. In his words, “44 doctors, nurses and paramedics saw multiple cases of preteen children who had been shot in the head or chest in Gaza… He personally identified 13 such cases in his two weeks there”.

That Israel, in addition to being an apartheid state, has gone completely rogue is no longer in doubt. In July this year, for example, a video was leaked of the gangrape of a male Palestinian prisoner by guards of the IDF at the Sde Teiman detention facility in Southern Israel. Commentators in Israel referred to this video as just the tip of the iceberg, but what followed is instructive. Ten soldiers were arrested and faced trial for this act, but not before a mob, led by government ministers, attempted to free them forcibly from detention. Another minister demanded an investigation to identify the individual who had leaked the video so that he could be tried for treason. An MP from the governing Likud Party defended the actions of the guards in Parliament, responding to a question by an Arab-Israeli MP with “If he is a Nukhba (Hamas militant), everything is legitimate to do! Everything!” Even the Minister responsible for Prison Services, Ben-Gvir, told Israeli media on the day of the reservists’ arrest that it was “shameful for Israel to arrest our best heroes”.

This race to the bottom doesn’t end there of course, and as the saying goes, the best is yet to come. As is well known, the Holy City of Old Jerusalem is home to the “Temple”, or as it is now known the Temple Mount. It refers to the two existing Islamic religious structures, the Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque, collectively known as Haram al-Sharif, and considered the third holiest site in Islam. However, according to the Tanakh or the Hebrew Bible, prior to these structures, the ‘First Temple’ was supposedly built on that very site in the 10th century BCE by King Solomon, and stood for five hundred years before being destroyed by the Babylonians. Almost a century later, it was replaced by the ‘Second Temple’ built by Cyrus the Great, only for it to be destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE. The New Testament holds that important events in Jesus’ life took place in the Temple, and the Crusaders attributed the name “Templum Domini” to the Dome of the Rock.

However, many Jews see the building of a “Third Temple” in Jerusalem as an object of longing and a symbol of future redemption, as it would announce the arrival of a new Messiah who would unite the flock and lead them to salvation. Incidentally, the promised land would incorporate the whole of Palestine, along with parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

Thus the religious significance and sensitivity of Temple Mount cannot be underestimated. Fortunately, as things stand Non-Muslims are not permitted to enter the two structures, while Jews are only allowed to pray at the Western Wall that runs along the side of the hill and is thought to be a remnant of the Second Temple. However, many Jews see the building of a “Third Temple” in Jerusalem as an object of longing and a symbol of future redemption, as it would announce the arrival of a new Messiah who would unite the flock and lead them to salvation. Incidentally, the promised land would incorporate the whole of Palestine, along with parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

But before its construction can be undertaken, it would require purification of the site and of the construction crew. That would, however, only be feasible, by sacrificing a red heifer, specifically bred to meet stringent biblical requirements. It would be required to be burnt alive at the Mount of Olives, adjacent to the Al Aqsa Mosque, and its ashes used to consecrate the holy ground and the people. The stuff of hopes and dreams for a tiny minority, with little hope of fulfilment in the modern world, or so one thought.

These cows represent a tangible step towards the construction of the Temple and fulfilment of the prophecy. The next obvious step in this tragedy will be the demolition of the Haram al-Sharif, for which dry rehearsals have already been undertaken. The consequences of such a step in the region are not difficult to visualise, but will it stop the extremists? Very unlikely.

However, in September 2022, an unprincipled collaboration between extreme Zionist religious leaders, Right-Wing Christian Evangelicals and the present Israeli Government allowed for five red heifers to be flown from Texas to Israel. Ironically enough, despite the Evangelicals being well-known for their antisemitic beliefs. Brought in as pets, to avoid existing restrictions on livestock, they are now kept in an archaeological park in Shiloh, an illegal Israeli settlement, near the Palestinian city of Nablus. These cows represent a tangible step towards the construction of the Temple and fulfilment of the prophecy. The next obvious step in this tragedy will be the demolition of the Haram al-Sharif, for which dry rehearsals have already been undertaken. The consequences of such a step in the region are not difficult to visualise, but will it stop the extremists? Very unlikely.

As Israel digs itself into a deeper hole, in the belief that it can kill its way to success, it finds that this year its GDP has collapsed from 4.8% in 2022 to 1.5%, with over 46000 small businesses having shut down. By some estimates, between 500,000 to 1 million Israelis have permanently emigrated. In addition, it finds itself short of weapons, ammunition, tanks and manpower as heavy casualties in the ongoing conflict have taken their toll. Yet, its arrogant leadership refuses to pay heed to that one cardinal rule about tackling insurgencies; they are a political problem and can only be resolved politically.

The question that it raises for us is do we really need such friends, and more importantly, are our commercial interests so important that we are willing to forego all that we hold sacred?

Clearly, if Israel refuses to change direction its days are numbered. After all its most steadfast ally, the United States, can only support so many losing causes. With Ukraine on the brink, an ascending Russo-China coalition to deal with and Taiwan increasingly under threat, an intransigent Benjamin Netanyahu is a liability, who may well find himself the target of a drone, be it American or Iranian. This is very likely despite Trump’s victory to become the 47th President of the United States. The question that it raises for us is do we really need such friends, and more importantly, are our commercial interests so important that we are willing to forego all that we hold sacred?

Feature Image Credit: Middle East Eye

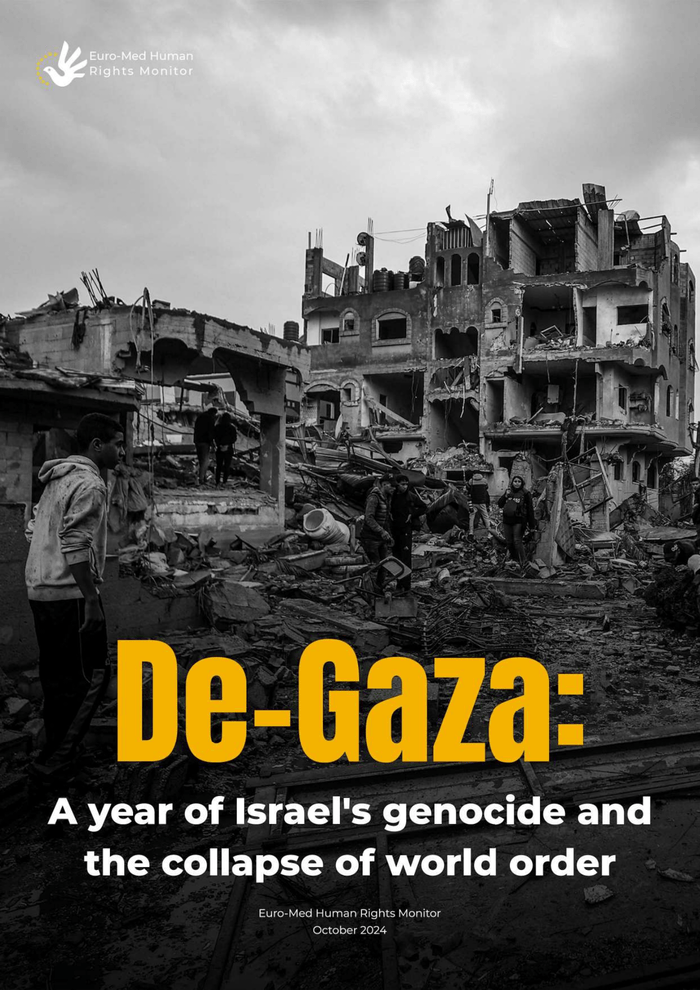

Image – De Gaza: reliefweb.int

Children of Gaza Image Credit: Middle East Eye – How Israel’s Genocide in Gaza sparked a protest movement in the UK.

Wailing Wall and Al Aqsa Mosque: Tourist Israel

Red Heifer Sacrifice Ritual Image: thetorah.com

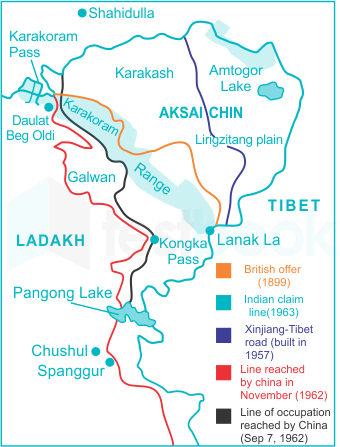

The opening skirmish of that conflict occurred in the North East with the capture, on 8th Sept, of the isolated Assam Rifles post at Dhola, on the southern slopes of the Thag La ridgeline. This post was surrounded and completely dominated by PLA positions on higher ground, and its loss was a foregone conclusion. The actual conflict commenced at approximately 0500 hours on 20th October, when the PLA launched a massive infantry attack, supported by artillery, on the 7 Infantry Brigade positions. The Brigade was deployed in a tactically unsound manner on direct orders of GOC 4 Corps, Lt Gen B M Kaul, along the Southern banks of the Namka Chu River over a 20 Km frontage instead of on the heights overlooking the river.

The opening skirmish of that conflict occurred in the North East with the capture, on 8th Sept, of the isolated Assam Rifles post at Dhola, on the southern slopes of the Thag La ridgeline. This post was surrounded and completely dominated by PLA positions on higher ground, and its loss was a foregone conclusion. The actual conflict commenced at approximately 0500 hours on 20th October, when the PLA launched a massive infantry attack, supported by artillery, on the 7 Infantry Brigade positions. The Brigade was deployed in a tactically unsound manner on direct orders of GOC 4 Corps, Lt Gen B M Kaul, along the Southern banks of the Namka Chu River over a 20 Km frontage instead of on the heights overlooking the river.