It goes without saying that at one time or the other we have all been victims of that old adage “20/20 hindsight”– the ability to clearlypick holes on past choices! Incidentally, the phrase was first used in 1962, when the British aeronautical journal, Flight International, noted “the newest expression in the US air transport business– namely, 20/20 hindsight”. While hindsight is a wonderful prism to critique the past, we cannot ignore the fact that inevitably, every choice is predicated on the situation being faced and the consequences of earlier choices. Moreover, it’s worth remembering that in choosing, as American lawyer and politician Joe Andrews so aptly put it, “the hardest decisions in life are not between good and bad or right and wrong, but between two goods or two rights”, which in some cases may well be choosing the lesser evil. Of course, it also goes without saying that the choices we make are to a great extent intrinsically moulded by our personalities, life experiences, ideological beliefs and preferences, and ‘primordial biases’.

Blog

-

What the Global Economy and Security Require

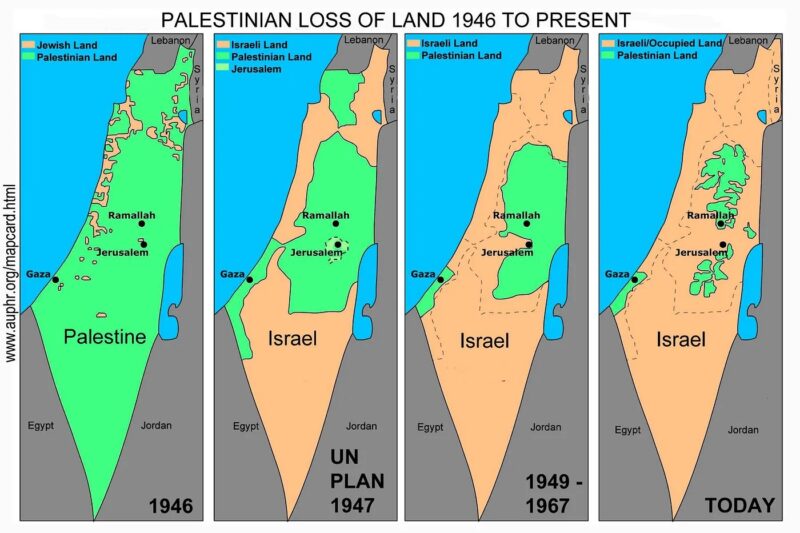

With the new year 2024 well underway, the world is afflicted with wars, economic challenges, and the larger issues of climate change impact that threaten the very survival of the planet. It is paradoxical to see that great powers are still focused on competition and conflict. The year ahead portends continued conflicts, wars, and the weaponisation of economic infrastructures, demonstrated by Israel’s genocidal war against the Palestinians. Carla Norrlof highlights the increase in geopolitical conflicts and the complex relationship between economics and security. The article, like most Western academics, looks from the American perspective. and may miss the larger worldview.

– Team TPF

This article was published earlier in Project Syndicate.

If America and its allies are to maximize both security and prosperity in the coming years, policymakers and strategists will have to understand the complex interplay of forces that is making the world more adversarial and fraught with risk. The global environment demands a comprehensive new economic-security agenda. The global order is undergoing significant changes that demand a new economic-security agenda.

From hot wars and localized insurgencies to great-power standoffs, geopolitical conflict has made the complex relationship between economics and security a daily concern for ordinary people everywhere. Complicating matters even more is the fact that emerging markets are gaining economic clout and directly challenging traditional powers’ longstanding dominance through new networks and strategic alliances.

These developments alone would have made this a tumultuous period marked by economic instability, inflation, and supply-chain disruptions. But one also must account for rapid technological advances – which have introduced new security risks (such as arms races and cyber threats) – as well as natural risks such as pandemics and climate change.

To navigate this dangerous new world, we must reckon with three interrelated dimensions: the effects of geopolitics on the global economy; the influence of global economic relations on national security; and the relationship between global economic competition and overall prosperity.

Each pathway sheds light on the multifaceted interplay between economics and security. We will need to understand all of them if we are to tackle the varied and complex challenges presented by our highly interconnected global system.

As recent years have shown, geopolitics can profoundly affect the global economy, reshaping trade, investment flows, and policies sometimes almost overnight. Aside from their devastating human toll, wars like the Russian invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s campaign in Gaza often reverberate far beyond the immediate theater of conflict.

For example, Western-led sanctions on Russia, and the disruption of Ukrainian grain exports through the Black Sea, caused energy and food prices to soar, resulting in supply insecurity and inflation on a global scale. Moreover, China has deepened its economic relationship with Russia following the mass exodus of Western firms in 2022 and 2023.

Similarly, Israel’s bombing of Gaza has destabilized the entire Middle East, especially tourism-dependent neighbouring countries such as Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon. Meanwhile, Yemeni Houthi rebels, long supplied by Iran, have been attacking cargo ships in the Red Sea, leading international shipping firms to suspend or adjust their routes and directly impeding trade through the Suez Canal – a major artery of global commerce.

We are witnessing the destabilizing effects of natural threats as well. The COVID-19 pandemic drove a massive shift away from cost-effective “just-in-time” supply chains to a “just-in-case” model aimed at strengthening resilience during disruptions. And, more recently, an El Niño-induced drought has diminished the capacity of the Panama Canal – another major artery of global commerce. Whether for geopolitical or ecological reasons, rerouting around these new bottlenecks inevitably increases shipping costs, causes delivery delays, disrupts global supply chains, and creates inflationary pressure.

Turning to the second dimension – the implications of global economic relations for national security – it is clear that countries will be more likely to adopt bold or aggressive security policies if they already have a web of economic ties that can either attract support or dampen opposition. China, for example, is counting on economically dependent countries within its Belt and Road Initiative to accept its political influence and longer-term bid for hegemony. Many countries also now rely on China for critical defence-related supply-chain components, which leaves them vulnerable diplomatically and militarily.

More broadly, global connectivity, in the form of economic networks and infrastructure, is increasingly being weaponized for geopolitical ends. As Russia’s war on Ukraine shows, economic ties can create dependencies that raise the cost of opposing assertive security policies (or even outright aggression). The implicit threat of supply disruptions has a coercive – sometimes quite subtle and insidious – effect on a country’s national security objectives. Owing to the network effects of the dollar system, the United States retains significant leverage to enforce international order through coercive sanctions against states that violate international norms.

Trading with the enemy can be lucrative, or simply practical, but it also alters the distribution of power. As Western governments learned over the past two decades, the advantages conferred by technological superiority can be substantially offset by forced technology transfers, intellectual property theft, and reverse engineering.

The third dimension – the relationship between global economic competition and prosperity – has been complicated by these first two dynamics, because the pursuit of material well-being now must be weighed against security considerations. Discussions in this area thus centre around the concept of economic security, meaning stable incomes and a reliable supply of the resources needed to support a given standard of living. Both Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan and President Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan reflect concerns that economic relations with China harm US prosperity.

The challenge for the US and its allies is to manage the tensions between these varying economic and security objectives. There is a potential conflict between adapting to market- and geopolitically-driven shifts in economic power and sustaining the economic strength to finance a military force capable of protecting the global economy. The US, as the dominant power, must remain both willing and capable of preserving an open, rules-based global economy and a peaceful international order. That will require additional investments in military capabilities and alliances to counteract territorial aggression and safeguard sea lanes, as well as stronger environmental policies and frameworks to distribute global economic gains according to market principles.

By attempting to mitigate security risks through deglobalization (reshoring, onshoring, and “friend-shoring”), we risk adding to the economic and security threats presented by a more fragmented world. Though economic ties with rivals can create dangerous dependencies, they also can act as a safeguard against hostility.

All governments will need to grapple with these tensions as they develop a new economic-security agenda. The world is quickly becoming more adversarial and fraught with risk. To maximize both security and prosperity, we will have to understand the complex interplay of forces that are creating it.

Feature Image Credit: India Today

-

Our Nearest Neighbours

In anticipation of a holiday gift, I kept asking members of my research team every week whether they noticed any anomalous object among the nearly hundred thousand objects imaged by the Galileo Project Observatory at Harvard University over the past couple of months. The reason is simple.

Finding a package from a neighbour among familiar rocks in our backyard is an exciting event. So is the discovery of a technological object near Earth that was sent from an exoplanet. It raises the question: which exoplanet? As a follow-up on such a finding, we could search for signals coming from any potential senders, starting from the nearest houses on our cosmic street.

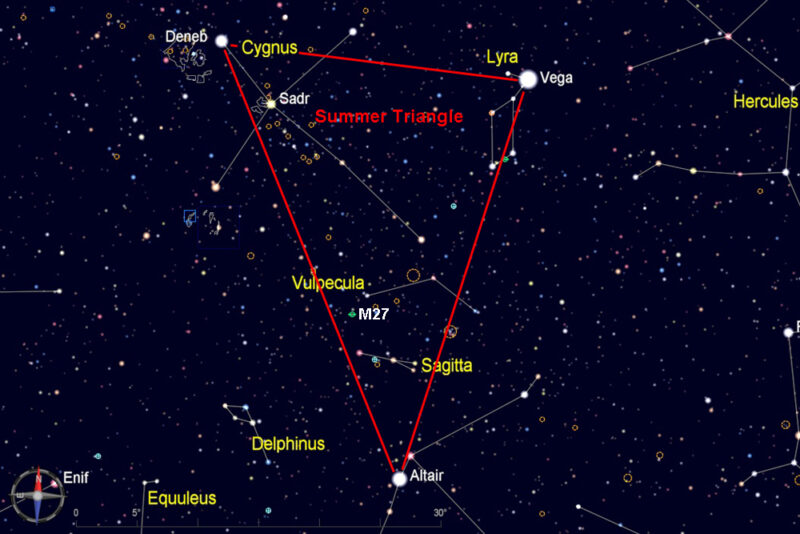

Summer Triangle, which consists of the three of the brightest stars in the sky–Vega, Deneb, and Altair. The Summer Triangle is high overhead throughout the summer, and it sinks lower in the west as fall progresses. For this star hop, start from brilliant blue-white Vega (magnitude 0), the brightest of the three stars of the Summer Triangle.

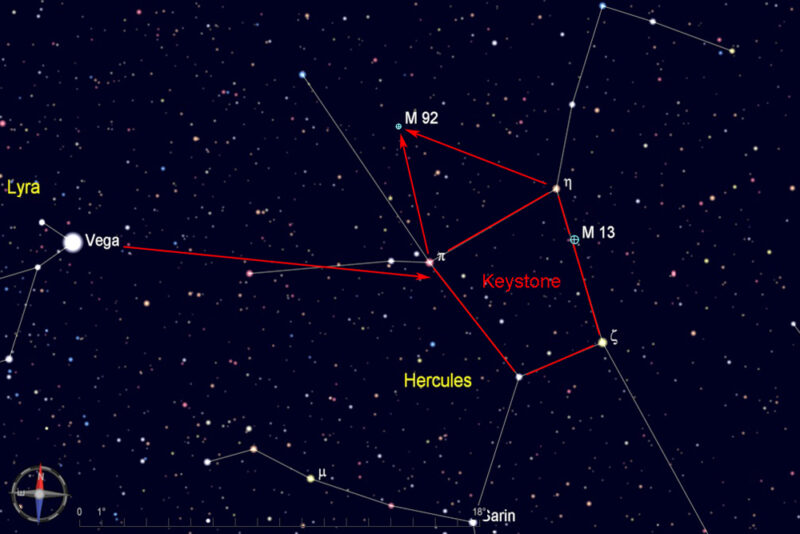

Summer Triangle, which consists of the three of the brightest stars in the sky–Vega, Deneb, and Altair. The Summer Triangle is high overhead throughout the summer, and it sinks lower in the west as fall progresses. For this star hop, start from brilliant blue-white Vega (magnitude 0), the brightest of the three stars of the Summer Triangle. From Vega, look about 15 degrees west for the distinctive 4-sided figure in the centre of Hercules known as the keystone. On the north side of the keystone, imagine a triangle pointing to the north, with the tip of the triangle slightly shifted toward Vega (as shown in the chart below). This is the location of M92.

From Vega, look about 15 degrees west for the distinctive 4-sided figure in the centre of Hercules known as the keystone. On the north side of the keystone, imagine a triangle pointing to the north, with the tip of the triangle slightly shifted toward Vega (as shown in the chart below). This is the location of M92.The opportunity for a two-way communication with another civilization during our lifetime is limited to a distance of about thirty light years. How many exoplanets reside in the habitable zone of their host star? This zone corresponds to a separation where liquid water could exist on the surface of an Earth-mass rock with an atmosphere. Also known as the Goldilocks’ zone, this is the separation where the temperature is just right, not too cold for liquid water to solidify into ice, and not too hot for liquid water to vaporize.

So far, we know of a dozen habitable exoplanets within thirty light years (abbreviated hereafter as `ly’) from Earth. The nearest among them is Proxima Centauri b, at a distance of 4.25 ly. Farther away are Ross 128b at 11 ly; GJ 1061c and d at 11.98 ly, Luyten’s Star b at 12.25 ly, Teegarden’s Star b and c at 12.5 ly, Wolf 1061c at 14 ly, GJ 1002b and c at 15.8 ly, Gliese 229Ac at 18.8 ly, and planet c of Gliese 667 C at 23.6 ly. These confirmed planets have an orbital period that ranges between a week to a month, much shorter than a year because their star is fainter than the Sun. This list must be incomplete because two-thirds of the count is within a distance of 15 ly whereas the volume out to 30 ly is 8 times bigger. Given that the nearest habitable Earth-mass exoplanet is at 4.25 ly, there should be of order four hundred similar planets within 30 ly. We are only aware of a few per cent of them.

But even if we identified all the nearby candidate planets for a two-way conversation, they would constitute a tiny fraction of the tens of billions of habitable planets within the Milky Way galaxy. Having any of the nearby candidates host a communicating civilization would imply statistically an unreasonably large population of transmitting civilizations for SETI surveys.

Most likely, any visiting probe we encounter had originated tens of thousands of light-years away. In that case, we will not be able to converse with the senders during our lifetime. Instead, we will need to infer their qualities from their probes, similarly to the prisoners in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, who attempt to infer the nature of objects behind them based on the shadows they cast on the cave walls.

It is better not to imagine your neighbours before meeting them because they might be very different than anticipated. My colleague Ed Turner from Princeton University, used to say that the more time he spends in Japan, the less he understands the Japanese culture. According to Ed, visiting Japan is the closest he ever got to meeting extraterrestrials. My view is that an actual encounter with aliens or their products would be far stranger than anything we find on Earth.

Personally, I am inspired by the stars because they might be home to neighbours from whom we can learn. The stars in the sky look like festive lights on a Christmas tree which lasts billions of years. A few days ago, a woman coordinated dinner with me as a holiday gift to her husband, who follows my work. At the end of dinner, they gave me a large collection of exceptional Japanese chocolates, which I will explore soon. In return, I autographed my two recent books on extraterrestrials for their kids with the hope that they would inherit my fascination with the stars.

Here’s hoping that our children will have the opportunity to correspond with the senders of an anomalous object near Earth. During this holiday season, I wish for a Messianic age of peace and prosperity for all earthlings as a result of the encounter with this gift.

Feature Image Credit: Messier 92 is one of two beautiful globular clusters in Hercules, the other being the famous M13. Although M92 is not quite as large and bright as M13, it is still an excellent sight in a medium to large telescope, and it should not be overlooked. The cluster is about 27,000 light years away and contains several hundred thousand stars. www.skyledge.net

Other Two Pictures in Text: www.skyledge.net

This article was published earlier in medium.com

-

How viable is Gandhi’s village today?

In a deeply troubled world, M.K. Gandhi’s vision for the village may offer a viable alternative, but is it too idealistic a solution?

THE world is in flux. Climate change-induced extreme weather events such as cyclones, forest fires, droughts, and unseasonal heavy rains have increased in number and intensity. Old wars are becoming chronic and new ones are breaking out at a worrying pace. Inequality is becoming even more extreme, which is clearly visible.

The world is looking for an alternative. Could Gandhian thought provide a way out?

In this context, the Gramshilpi programme of Gujarat Vidyapith, based on Gandhian thought, is worth studying to understand whether a non-violent development path based on a bottom-up approach can provide a viable alternative.

The author Neelam Gupta, a journalist by trade, was commissioned by Gujarat Vidyapith to study the programme and write about it. The book under review is the result of that effort.

Gandhi, in Hind Swaraj, calling Western Civilisation “evil”, said that Indian civilisation could provide an alternative. He suggested that the alienating Western education system had to be replaced by ‘nai talim’ (new education).

He set up Gujarat Vidyapith in Ahmedabad in 1920 to teach an alternative curriculum in tune with his conception of education. He believed that this could lead to more meaningful higher education in India. If it succeeded, it could be replicated and change India’s education system.

The Gramshilpi programme of Gujarat Vidyapith based on Gandhian thought is worth studying to understand whether a non-violent development path based on a bottom up approach can provide a viable alternative.

Did he succeed?

In a world that is increasingly following the principles of marketisation that run contrary to Gandhian principles, the experiment has faced huge difficulties.

Between 1920 and 1965–70, around 100 youth who graduated from the Vidyapith went to remote and backward areas and lit the flame of new thinking. After 1965–70, even though the number of graduates increased, fewer and fewer of them went to the villages and, finally, the flow stopped.

The Vidyapith becoming a University Grants Commission (UGC) institution in the 1960s changed the composition of teachers as they had to be selected as per the UGC norms and often were not in tune with Gandhian ideas.

The emergence of foreign-funded non-governmental organisations (NGOs) engaging in projects-based work changed the attitude of the students. They did not want to stay in the villages to bring about change through collective endeavours. Students from the villages who came to the cities did not want to go back. Even their parents did not want them to return to the villages.

Start of the programme

The triumvirate of Arun Dave, Sudershan Ayengar and Rajendra Khimani was in place in Vidyapith in 2005. They felt that an attempt should be made to change the thinking of the youth via appropriate training.

The result was the start of the Gramshilpi Yojana in 2007. The Centre for Environment Education was also roped into the scheme since it had been working in the rural areas. The programme design evolved over the next five years to take its final shape.

The scheme had three important components. First, the gramshilpi (literally village sculptor, as in, shaper of the village) would stay in a village of his choice for the rest of his life. Second, their expenses of stay would be borne by the village. Third, Gujarat Vidyapith would always stand by the gramshilpi. The goal of the scheme was to transform the village as per Gandhi’s vision of Gram Swaraj.

Author’s experience

The author has produced the book based on an extensive survey of the work of the Vidyapith and visits to the villages of the gramshilpis. The project started in 2018. She wanted to understand the motivation of these people who were foregoing a comfortable city life for one of struggle in a village.

She faced difficulties in assessing the impact of the work of gramshilpis since there was no primary or secondary data. The gramshilpis did not remember the details of the work done earlier and language was a barrier in talking with the villagers to get their perspective.

The Vidyapith assigned Praveen Dulera to travel with the author and help her. This, to an extent, helped overcome the language barrier. However, the villagers were often reluctant to talk or could not explain what they had in their minds.

Gandhi, in Hind Swaraj, calling Western Civilisation “evil”, said that Indian civilisation could provide an alternative. He suggested that the alienating Western education system had to be replaced by ‘nai talim’ (new education).

Three to four days were spent in the village of each gramshilpi. The author felt this was inadequate to interview the gramshilpi, and meet the villagers and the officials to get their feedback and perspective.

Achievements of the programme

Some of the achievements of the programme listed by the author are:

a) Decrease in the dropout rate of children

b) Higher retention by children

c) Change in the way teachers teach

d) Parents understanding the importance of education, especially for girls

e) Positive impact on the life of abandoned children

f) Reduction in poverty as a result of mixed cropping

g) Reduction in indebtedness and suicide among farmers

h) Improvement in the status of farmers as their income increased.

This is an impressive list of impacts on the life of the villages where gramshilpis were working.

The gramshilpis and their work

Between 2007 and 2015, 52 people came to join the Gramshilpi programme, 37 took instructions, but only 10 became gramshilpis. Most left within two to three years, and a few were found to be unsuitable and asked to withdraw. Those who left did so since economic security was not assured and life would be one of struggle.

Most of the pages of the book describe the experiences of the gramshilpis. It emerged that there was no one model of development that the gramshilpis followed since the situation faced by each of them varied from village to village. So, the programme for each had to be tailor-made to the prevailing village conditions.

The work of nine of the gramshilpis is described in detail. Their personal challenges, the village situation and the challenges, and how they were met are well described.

So, who are these courageous and determined people?

Jaldeep Thakur and Dashrath Vaghela are based in North Gujarat in areas close to the Rajasthan desert. These are poor and backward areas. Ashok Chaudhury, Ghanshyam Rana, Jettsi Rathor, Gautam Chaudhury, Neelam Patel and Mohan Mahala are based in South Gujarat, which has plenty of rain and is hilly. This is also the area from where Gandhi emerged. Radha Krishna is based in Agra district of Uttar Pradesh.

Assessment of the programme

The author says that though the programme is only 13 years old, the period is long enough to assess it. The most important issue was, how much has the programme enhanced peoples’ awareness? Especially since the idea underlying the programme was to do social work via social involvement.

She finds that the inspiration to join the programme came from Gandhi’s thought which the gramshilpis became aware of in the Vidyapeeth. The training turned the idea into a resolve to go to the villages. Broadly speaking, the gramshilpis worked on two fronts— social and economic.

The emergence of foreign funded non-governmental organisations (NGOs) engaging in projects-based work changed the attitude of the students. They did not want to stay in the villages to bring about change through collective endeavours.

The education of children was a major component of social activity. Not only did this impact the children, but even the attitude of the parents changed. The educational programme was based on Gandhi’s nai talim.

But the author rues that the education did not prepare the children to work in the forest and in agriculture and, through that make a living.

Health and cleanliness was another important social issue. However, the author says that consciousness about keeping the entire village clean could not be created. On the health front also, there was a limited success, with women continuing to suffer and superstition (andhvishwas) persisting. Limited success was achieved in improving nutrition and reducing addiction to drinking and smoking.

The work on the economic front helped improve family incomes and the way work was traditionally done. For instance, farming changed to mixed cropping. Consequently, indebtedness decreased.

Adulteration of mustard oil decreased when one Radhakrishan set up a mill at home and sold the oil at a lower profit margin. Other suppliers changed their approach. A person named Jaldeep set up a women’s milk cooperative, which gave women self-confidence, and this changed the attitude of the entire village. Violence towards women declined, and in Gandhi’s words, ‘the mute got a voice’.

Other economic activities included making pickles, producing organic manure, preparing youth for facing interviews for jobs, forming youth self-help groups for farming and creating minor irrigation facilities.

However, the author points out that while the farmers came together, they did not get organised. Further, due to rising expectations, marketisation, taking of loans and changes in food habits increased.

Conservation of water could not be made a part of good practices. Rather than making people independent, many became dependent on the gramshilpis for help. Though in some villages, the situation of women improved in totality, they remained at the margins.

The author asks, “Gramshilpis have done great work, but why are there deficiencies?”

She identifies several causes. Setting up trusts by gramshilpis for their work made the villagers dependent on outside donations.

Next, she identifies several shortcomings in the training imparted to gramshilpis. First, they needed more hands-on experience in village life. Second, gramshilpis were not trained in self-assessment. They did not keep a diary of their work which could help them assess their progress and failures. Thus, they did not prepare an annual report. They did not often remember what they had done earlier. Third, they were not trained to become economically self-sufficient in the village. Finally, they did not develop a holistic perspective of village life.

Conservation of water could not be made a part of good practices. Rather than making people independent, many became dependent on the gramshilpis for help. Though in some villages the situation of women improved in totality they remained at the margins.

The author also points to the positives of the programme. First, the autonomy that the gramshilpis had in pursuing their goals. This helped in commitment, creativity, self-correction and leadership.

Second, the flexibility of the programme. Gujarat Vidyapith kept changing its view as difficulties arose. For instance, initially, it had decided to support the gramshilpis for two years only, but later as difficulties arose, this period was extended.

Third, guidance from Vidyapith was always available in case of difficulties. Three meetings of all gramshilpis are held annually to collectively exchange ideas and assess the difficulties.

The author says that at the end of the process, she could appreciate the importance of Gandhi’s work. She also understood that with commitment and principles, even in today’s materialistic world, educated youth can work in the villages with the idea of service.

Further, if the basis of development is swavalamban and atmanirbharta, solutions to the country’s and world’s problems can be found.

The author says that at the end of the process, she could appreciate the importance of Gandhi’s work. She also understood that with commitment and principles even in today’s materialistic world, educated youth can work in the villages with the idea of service.

The author offers constructive suggestions to improve the programme. These relate to improvements in training, arrangements for stay in the village, how to organise and create cooperatives, creation of leadership among women and how to improve marketing skills.

There are also suggestions regarding education, health, nutrition, protection of the environment and an increase in local production.

The book is about the difficulties in the present-day world in fulfilling Gandhi’s idea of creating swaraj due to the dominant process of marketisation. So, it is a must-read for all those interested in alternatives to the present systems.

This Review was published earlier in theleaflet.in

Feature Image Photo: from Sabarmati Ashram Museum

-

Strategies: hierarchy or balancing Purpose, Aims and Means?

At the beginning of his famous first chapter, Clausewitz defines war as mentioned above within a hierarchy of purpose, aims, and means. His renowned formula is related to this definition. At the end of the same chapter, nevertheless, he introduces the consequences for the theory of war from this initial reasoning about the nature of war and states: “Our task, therefore, is to develop a theory that maintains a balance between these three tendencies, like an object suspended between three magnets”

Strategy Bridge

“The Strategy Bridge concept leads to battle-centric warfare and the primacy of tactics over strategy.”

At the outset, I would like to emphasise that in war and in violent action, justifiable ends do not legitimate all means. But I won’t solely treat the means applied by Hamas on October 7th, nor that of the Israel defence forces afterwards. Nevertheless, if someone argued that the ends justify all means, this would have to be applied to both sides. I want to highlight more principal arguments concerning the ‘end-aims-means’ relationship by contrasting a mere hierarchical approach, which is, in my view, leading to a reversal of ends and means, and a floating balance of them. The task of coming to a proper appreciation of Clausewitz’s thoughts on strategy is actually to combine a hierarchical structure with that of a floating balance. This article examines the relation of purpose, aims and means in Clausewitz’s theory and highlights that this relation is methodologically comparable to the floating balance of Clausewitz’s trinity. Modern strategic thinking is characterised by the end, way (aim), means relationship and the concept of the ‘way’ as the shortest possible connection between ends and means (consider, for instance, Colin Gray’s concept of a strategy bridge[1]). This notion stems from a very early text of Clausewitz: ‘As a result each war is raised as an independent whole, whose entity lies in the last purpose whose diversity lies in the available means, and whose art therein exists, to connect both through a range of secondary and associated actions in the shortest way.’

Nevertheless, here we can detect the fundamental difference in many of Clausewitz’s interpretations, which understand strategy as the shortest way of connecting purpose and means (battle and combat). Within this quote, Clausewitz speaks of war as an independent whole, a notion which he later rejects fervently. A central distinction is the concept to which the means attaches: the Taoist tradition and Sun Tzu hold that the means connects directly to the political purpose of the war; in contrast, for Clausewitz, the means attaches to an intermediary aim within a war, which must be sequentially achieved prior to the fulfilment of the war’s political purpose. The distinctive feature of the Taoist tradition is that strategy as a “way” effectively becomes tactics, in the sense that there exists no “strategic” aim, in the meaning of an intermediate military “strategic” war aim inserted between the political purpose of the war and tactical combat.

Battle-centric Warfare: Winning battles and losing the War

If strategy is nothing else than the direct way of linking the political purpose with the means, understood as combat, this understanding results in a ‘battle-centric’ concept of warfare that privileges tactical outcomes. One might attribute the loss of the Vietnam War, as well as the defeat of the US in Afghanistan and Iraq, to this misunderstanding about battle. In the early 1980s, Colonel Harry G. Summers Jr wrote a most influential work about the faults made in the Vietnam War. He observed that the US Army won every battle in Vietnam but finally lost the war. Summers recounts an exchange between himself and a former North Vietnamese Army officer some years after the war. It went something like this: Summers: ‘You never defeated us in the field.’ NVA Officer: ‘That is true. It is also irrelevant.’ [2]Winning battles does not necessarily lead to winning the war, and not only in this case. The same point can be made about Napoleon’s campaign in Russia. Napoleon won all the battles against the Russian army but lost the campaign. It was precisely this observation that led Clausewitz to denounce battle-centric warfare.

‘War is thus an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will,’ Clausewitz wrote at the beginning of his famous first chapter of On War (75).[3] ‘Force … is thus the means of war; to impose our will on the enemy is its purpose’, he continued. ‘To secure that purpose, we must make the enemy defenceless, which, in theory, is the true aim of warfare. That aim takes the place of the purpose, discarding it as something not actually part of war’ (75). This seemingly simple sentence reveals the core problem: what does it mean that the aim ‘takes the place’ (in German: vertritt) of the purpose? Are they identical or different? To put it bluntly, At the beginning of his famous first chapter, Clausewitz defines war as mentioned above within a hierarchy of purpose, aims, and means. His renowned formula is related to this definition. At the end of the same chapter, nevertheless, he introduces the consequences for the theory of war from this initial reasoning about the nature of war and states: “Our task, therefore, is to develop a theory that maintains a balance between these three tendencies, like an object suspended between three magnets” (89).[4] In relation to the concept of strategy, we must combine a hierarchical understanding of the purpose-aims-means-rationality with that of a floating balance of all three.

Presenting any of these elements as an absolute would be artificially to delimit the analysis of war, as the components are interdependent. Clausewitz’s solution is the ‘trinity’, in which he defined war by different, even opposing, tendencies, each with its own rules. Nevertheless, since war is ‘put together’ in this concept of three tendencies, it is necessary to consider how these tendencies interact and conflict simultaneously rather than one being absolute. Clearly, if we go to war, there is a purpose for that war, and different purposes for war are possible. Each of these possible purposes is connected with different achievable military aims, and finally, each aim can be achieved by various means. The question, therefore, is whether all three are incorporated into a hierarchy or whether their relationship must be understood as a floating balance among them.

Purpose, Aims, and Means in War

Clausewitz explains this dynamic relationship of purpose, aims and means in war in Chapter Two of Book One. At the beginning of Book One, Chapter Two, Clausewitz writes that ‘if for a start we inquire into the [aim] of any particular war, which must guide military action if the political purpose is to be properly served, we find that the [aim] of any war can vary just as much as its political purpose and its actual circumstances’ (90). The consequence of this proposition is that not every aim and means serves a given purpose. The problem of the relationship between purpose and aims is that each element of the purpose-aims-means construct has a rationality of its own, which Clausewitz emphasises in his proposition that war has its own grammar, although not its own logic. He writes, for example, ‘we can now see that in war many roads lead to success, and that they do not all involve the opponent’s outright defeat.’ Clausewitz then summarises that there exists a wide range of possible ways (94) to reach the aim of war and that it would be a mistake to think of these shortcuts as rare exceptions (94). For example, Clausewitz wrote: ‘It is possible to increase the likelihood of success without defeating the enemy’s forces. I refer to operations that have direct political repercussions, that are designed in the first place to disrupt the opposing alliance’ (emphasis in the original) (92).[5]Another prominent example, Clausewitz emphasised, was the warfare of Frederick the Great. He would never have been able to defeat Austria in the Seven Years’ War if his aim had been the outright defeat of Austria. Clausewitz concludes if he had tried to fight in this manner, ‘he would unfailingly have been destroyed himself.’ (94). After explaining other strategies besides the destruction of the enemy armed forces, he concludes that all we need to do for the moment is to admit the general possibility of their existence, the likelihood of deviating from the basic concept of war under the pressure of particular circumstances (99). But the main conclusion is that in war, many roads may lead to success – but the reverse is true, too, not all means are neither guaranteeing success nor are legitimate.[6]

But the main conclusion is that in war, many roads may lead to success – but the reverse is true, too, not all means are neither guaranteeing success nor are legitimate.

Why is that so? Although Clausewitz finishes Chapter 2 of Book I with the notion that the ‘wish to annihilate the enemy’s forces is the first-born son of war’ (99), he emphasises that at a later stage and by degrees’ we shall see what other kinds of strategies can achieve in war’ (99). Nevertheless, he gives us two clues in this chapter. First, that war is not an independent whole but – an extension of the political sphere: that war has its own grammar but not its own logic.[7] Second, in my interpretation of Clausewitz, the difference between attack and defence represents a distinction between self-preservation and gaining advantages in warfare. Already in Chapter Two, he articulates the ‘distinction that dominates the whole of war: the difference between attack and defence. We shall not pursue the matter now, but let us just say this: that from the negative purpose [comes?] all the advantages, all the more effective forms, of fighting, and that in it is expressed the dynamic relationship between the magnitude and the likelihood of success’ (94).

My thesis is that Clausewitz is trying to combine the Aristotelian difference between poieses and praxis in his writings – an instrumental view of war for political purposes with the performance of the conduct of war, not just with the execution of the political will. Whereas for the early Clausewitz, the ‘purpose’ is a moment within the war, he later opposes this position, emphasising that this purpose is located outside of the actual warfare. With this differentiation of purposes in war and the purpose of war, Clausewitz covers a fundamental difference between various forms of action, which was initially developed by Aristotle and remains even today. The practical philosophy of Aristotle is based on the basic distinction of techne, as based on poiesis and phronesis, and praxis, based on performance and practical knowledge. Techne is technical, instrumental knowledge.

In contrast, phronesis or praxis of action can be characterised as performance in warfare. If we compare different purposes for going to war with each other, we are close to what Max Weber called the “value rationality” of purposes. Although Max Weber sometimes seems to overemphasise the difference between the rationality of purposes and military aims, his differentiation is useful to shed light on Clausewitz’s theory. Value rationality is primarily about the relationship of different purposes to one another, which can be classified into a hierarchy of purposes. The subordination of warfare to the shaping of international order, as Clausewitz puts it, is ‘value-rational’ as defined by Max Weber. By contrast, “action rationality” is a principle of action exclusively oriented to achieving a particular military aim through the most effective means and rational consideration of possible consequences and side effects.

Clausewitz initially makes a two-fold distinction between the purpose-aims-means relationship: first, as a value rationality, in which we find a hierarchical relationship starting from the purpose at the top, with aims and means subordinated respectively; second, as a process rationality, in which the military aim as the object of practical action is the output of the purpose-aim-means relationship.

He made this distinction at times only implicitly based on the different connotations of the concept of purpose. In part, Clausewitz differentiates between the purpose of war and the purpose in war. He used the same terms throughout, providing various contents from which this distinction could be deduced. Henceforth we need to have a further look at his use of terms and concepts.

Beginning with his earliest writings, Clausewitz asserted that war has a purpose. In his Strategie (Strategy), written in 1804, he wrote that the ‘purpose of the war’ can be: ‘Either to destroy the enemy completely, to remove their sovereignty, or to prescribe the conditions for peace.’ The destruction of the enemy forces is the ‘more present purpose’ of war. If the purpose of war, however, is the destruction of the enemy forces, is it a purpose that is realised within warfare?[8] The problem is that the destruction of the enemy moves from being a means to an aim in and of itself. In contrast to such an understanding of the purpose-aims-means rationality, for Clausewitz, the military aim within the war is an intermediary dimension between purpose and means. In his later writings, Clausewitz replaces the term’ purpose in war’ through the terms’ aims’ and ‘goals in warfare’ [(he uses the same German term Ziel for both aim and goal).

The late Clausewitz emphasises that the purpose of war lies outside the boundaries of the art of warfare. He argues that one must always consider peace as the achievement of the purpose and the end of the business of war. (215) ‘Even more generally, the consideration of the use of force, which was necessary for warfare, affects the resolution for peace. As the war is not an act of blind passion but is required for the political purpose to prevail, this value must determine the size of our own sacrifices. Once the amount of force and thus the extent of the applied force is being so large that the value of the political purpose was no longer held in balance, the violence must be abandoned, and peace be the result.’ (217)

Additionally, one has to take into account the counter-actions of the opponent. Clausewitz emphasises this difference in his chapter about the theory of war, Book Two: ‘The essential difference is that war is not an exercise of the will directed at inanimate matter, as in the case with the mechanical arts, or at matter which is animate but yielding, as in the case with the human mind and emotions in the fine art. In war, the will is directed at an animate object that reacts’. (149). Hence, Clausewitz’s final achievement is not a strategy that could be applied to all kinds of war but a reflection on the art of warfare, the performance of warfare within a political purpose.

If, as it seems to Clausewitz, the purpose of war lies outside of warfare and war is determined only as means for this purpose, then a technical, instrumental understanding of the war is thereby intended. But this is not the whole of Clausewitz. He also emphasises praxis, performance and practical knowledge. If the purpose lies within warfare, this does not contain a complete identity of the goal of martial action with its execution. In this case too, the purpose is not war for war’s sake. My conclusion is that Clausewitz is really trying to combine the Aristotelian difference between poieses and praxis in his writings – an instrumental view of war for political purposes with the performance of the conduct of war, not just with the execution of the political will.

Further dimensions of the concept of Purpose in Clausewitz

According to Herfried Münkler, Clausewitz makes a distinction between an existential and instrumental view of war. If purpose exists at the top of a hierarchy in the purpose-aims-means relationship, there is an assumption that war is instrumental, in the sense that there is a choice between different purposes, thus identifying the purpose in terms of Max Weber’s value rationality. However, if war is “existential”, in that the only purpose is the survival of the state, the hierarchy of the relationship is reversed, as the means by which the enemy is defeated gains primacy, which accords with a process of rationality. Clausewitz summarised the difference between both concepts of purpose: ‘Where there is a choice of purpose, one may consider and note the means, and where only one purpose may be, the available means are the right ones.’[9]

A pure process of rationality can lead to the fact that the military aim and means of warfare become the purpose in themselves. It is for characterising war in this manner, as an instrument facing inwards on itself, rather than outwards to a wider political purpose, that the early Clausewitz can be criticised. He adopted the Napoleonic model from Jena, trying to seize its successes systematically and, without considering the social background of France, to generalise it as an abstraction. In his critique of Clausewitz, Keegan wrote that the military develops war cultures, which correspond with their social environment. If, however, war is seen as purely instrumental and the connection to this environment is cut, then the danger of blurring the military boundaries threatens potentially endless violence. In this view, the roots of Clausewitz’s image of war refer back to the origins of the modern age, which was characterised by the full possession of civil rights, the general right to vote and compulsory military service, all of which completed the portrait of the citizen soldier and the ‘battle scenes’ of the people’s army.

The question for today is whether the revolution in military affairs as well as fourth and fifth-generation warfare (5th generation warfare is partisan warfare applied by states or state-like entities like Hamas) are tempting to a primacy of the means and aims over meaningful purposes, a primacy of tactics over strategy and the ‘art of war’, which is in Clausewitz’s view even surpassing strategy.

The French model was, in fact, adapted for the Prussian circumstances: a revolutionary people’s army in the service of the raison d’ état – but without ‘republic’ (meaning a democratically constituted system of government). In this form, Clausewitz’s theory was proved and began to be used later for multiple purposes. It started its triumphant advance through the general staff throughout the war ministries of the world. In Keegan’s view, the result of this process was the general armament of Europe in the 19th century and its excessive increase in the 20th century.[10] Keegan left unmentioned that Clausewitz’s theory of war had yet to be bisected to fulfil this function, especially by the German general staff in the First World War. Nevertheless, his criticism revealed a fundamental problem of modern war: the separation of potential options for warfare from socially meaningful purposes. In World War I, tactics replaced strategy.

Although the understanding of the strategy of the early Clausewitz was, in fact, one of an aim or goal independent from the political realm within warfare, the definition of purpose of the later Clausewitz is based on the political purpose outside of warfare. There are still passages in the final version of On War in which Clausewitz does not differentiate clearly between purpose and aims. The question for today is whether the revolution in military affairs as well as fourth and fifth-generation warfare (5th generation warfare is partisan warfare applied by states or state-like entities like Hamas) are tempting to a primacy of the means and aims over meaningful purposes, a primacy of tactics over strategy and the ‘art of war’, which is in Clausewitz’s view even surpassing strategy.

Notes:

[1] The relevant discussions may be found in the following books: Echevarria, A. 2007. Clausewitz and Contemporary War. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Gray, C. 1999. Modern Strategy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Herberg-Rothe, A. 2007. Clausewitz’s Puzzle: The Political Theory of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Keegan, J. 1994. A History of Warfare. London and New York: Vintage; Simpson, E. 2012. War from the Ground Up: Twenty-First Century Combat as Politics. London: Hurst; Strachan, H. 2007. Clausewitz’s OnWar. Atlantic Monthly Press, New York; von Ghyczy, T., Bassford, C. and von Oetinger, B. Clausewitz on strategy. Inspiration and insight from a master strategist. Hoboken: Wiley; Heuser, B., 2010, The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Heuser, Beatrice 2010, The Strategy Makers: Thoughts on War and Society from Machiavelli to Clausewitz. Praeger Security International:

[2] For details, see Herberg-Rothe, Andreas, Clausewitz’s puzzle. Oxford University Press: Oxford 2007. Clausewitz, Carl von; 1990. Schriften, Aufsätze, Studien, Briefe, vol. 2, ed. W. Hahlweg. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck&Ruprecht.; Clausewitz, Carl von, 1992. Historical and Political Writings, ed. P. Paret and D. Moran, 1992. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; Clausewitz, Carl von, Politische Schriften [Political Literature], ed. H. Rothfels. Munich: Drei Masken Verlag. 1922.

[3] The numbers in brackets are references to Clausewitz, Carl von, On War. Translated and edited by Peter Paret and Michael Howard. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1984. As translation is a highly tricky process, I have tried to make some translations of my own only in some cases, especially in trying to distinguish the German terms „Zweck“ and „Ziel“. These terms have been translated as purpose, object, objective, ends, and as aims, goals and sometimes even ways by Howard and Paret. My main intention in this article is to distinguish between purpose and aims. It might be that the great variety of the translations has contributed to the underestimation of the difference between the purpose of the war and the goal within the war. Although they are closely connected with each other, I follow Clausewitz’s assertion that the same purpose could be reached by pursuing different goals.

[4] With this notion, we can explain the difference between Clausewitz’s real concept of the trinity and trinitarian warfare, which is not directly a concept of Clausewitz, but an argument made by Harry Summers, Martin van Creveld and Mary Kaldor. In trinitarian warfare, the three tendencies of war are understood as a hierarchy, whereas Clausewitz describes his understanding of their relationship as a floating balance In my view, each war is differently composed of the three aspects of applying force, the struggle or fight of the armed forces and the fighting community the fighting forces belong to; based on this interpretation I define war as the violent struggle of communities; see Herberg-Rothe, Clausewitz’s puzzle.

[5] This reference seems to strengthen the difference made by Emile Simpson between the use of armed force within a military domain that seeks to establish military conditions for a political solution on one side and the use of armed force that directly seeks political as opposed to specifically military outcomes; Simpson, War from the ground up, p. 1.

[6] The confusion about the difference between Zweck (purpose) of and Ziel (aims) in warfare concerning Clausewitz might be additionally caused by his own insufficient differentiation in this chapter.

[7] For Clausewitz’s concept of Policy and politics, see Herberg-Rothe, Clausewitz’s puzzle, chapter 6.

[8] Clausewitz, Carl von, Strategie aus dem Jahre 1804 mit Zusätzen von 1808 und 1809 (Strategy from the Year 1804 with Additions from 1808 and 1809). In EB, Verstreute Kleine Schriften (Small Scattered Writings), pp. 3-61, here pp. 20-21.

[9] Clausewitz, Carl von, Historisch-politische Aufzeichnungen von 1809 (Historical-Political Records of 1809). In: Clausewitz, Carl von, Politische Schriften (Political Literature), p. 76.

[10] . Keegan, Kultur des Krieges (The Culture of War), in particular, p. 543; Naumann, Friedrich, An den Ufern des Oxos (On the banks of the Oxos). John Keegan corrects Carl von Clausewitz. In: Frankfurter Rundschau from 17.6.98, p. ZB 4.

Feature Photo Credit: Dennis Jarvis – War on the Rocks

-

The Philippines’ History Curriculum: Origins and Repercussions

Background

The Philippines, a twice-colonized archipelago that achieved its complete independence in 1946, is a member of the ASEAN and an essential player in the geopolitics of the Southeast Asia region. Its status is owed mainly to its rapidly growing economy, of which the services industry is the most significant contributor, comprising 61% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bajpai, 2022). Services refer to various products – for example, business outsourcing, tourism, and the export of skilled workers, healthcare workers, and labourers in other industries. In recent years, a growing demand for qualified professionals has grown as the economy has grown, thus necessitating more robust educational systems (Bajpai, 2022). Although the Philippines has a high literacy rate, hovering at around 97%, the efficacy of its educational system is often called into question (“Literacy Rate and Educational Attainment”, 2020). Administration oversight, infrastructural deficiencies, and pervasive corruption in the government that seeps into the entities responsible for educational reform are significant issues that legitimize these doubts (Palatino, 2023). However, reforming the current flaws in the system requires an understanding of the basic underlying structure of the country’s educational system as it is today. This fundamental understanding can help clarify specific political trends in the status quo and highlight the importance of proper historical education in developing a nation. Despite its ubiquity in nearly every curriculum, the study of history as a crucial part of the education system is often not prioritized, leading to an underdeveloped understanding of the society’s culture and previous struggles with colonial exploitation. Though it is present in the Philippines’ education today, it continues to change because of its historically dynamic demographic and political atmosphere.

The Philippines, a twice-colonized archipelago that achieved its complete independence in 1946, is a member of the ASEAN and an essential player in the geopolitics of the Southeast Asia region. Its status is owed mainly to its rapidly growing economy, of which the services industry is the most significant contributor, comprising 61% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bajpai, 2022). Services refer to various products – for example, business outsourcing, tourism, and the export of skilled workers, healthcare workers, and labourers in other industries. In recent years, a growing demand for qualified professionals has grown as the economy has grown, thus necessitating more robust educational systems (Bajpai, 2022). Although the Philippines has a high literacy rate, hovering at around 97%, the efficacy of its educational system is often called into question (“Literacy Rate and Educational Attainment”, 2020). Administration oversight, infrastructural deficiencies, and pervasive corruption in the government that seeps into the entities responsible for educational reform are significant issues that legitimize these doubts (Palatino, 2023). However, reforming the current flaws in the system requires an understanding of the basic underlying structure of the country’s educational system as it is today. This fundamental understanding can help clarify specific political trends in the status quo and highlight the importance of proper historical education in developing a nation. Despite its ubiquity in nearly every curriculum, the study of history as a crucial part of the education system is often not prioritized, leading to an underdeveloped understanding of the society’s culture and previous struggles with colonial exploitation. Though it is present in the Philippines’ education today, it continues to change because of its historically dynamic demographic and political atmosphere.Origins of the Education System

To begin with, the educational system, and especially the modes of linguistic and history education in the country, have been heavily influenced by the major powers that occupied it – namely, the Spanish Empire and the United States. The impact of these periods of colonization can be seen most significantly in the historical education and consciousness of the general population, as well as the propagation of the English language. The Philippines possesses a great deal of linguistic diversity, especially among indigenous groups – an estimated 170 distinct languages in the country today (Postan, 2020). However, even in pre-colonial times – typically considered by historians to be the years before 1521 – the most common language in the country was Old Tagalog, and other indigenous languages are still spoken today (Stevens, 1999). Records suggest that the Spanish did not forcefully erase indigenous languages spoken in the country. However, they did conduct business and educational institutions in Spanish, leading to the language being used almost exclusively amongst the upper classes – the colonizers, business people in the country, and other influential figures in the empire. Though there were attempts to conduct education in Castilian Spanish, priests and friars responsible for teaching the locals preferred to do so in local languages as it was a more effective form of proselytization. This cemented the reputation of Spanish as a language for the elite, as the language was almost exclusively limited to those chosen to attend prestigious institutions or government missions that operated entirely in Spanish (Gonzales, 2017). In terms of popularising education to expose a broader audience to Christianity, the Spanish also established a compulsory elementary education system. However, restrictions existed based on social class and gender (Musa & Ziatdinov, 2012). Because of this, although the influence of Spanish on local languages can be seen through the borrowing of certain words, indigenous and regional languages were not supplanted to a large extent, though their scripts were Latinised in some instances to make matters more convenient for the Spanish (Gonzales, 2017). However, the introduction of Catholicism to a large segment of the population and a more organized educational system are aspects of Spanish rule that remain in Philippine society today, as do the negative ramifications of the social stratification that was a significant element of its occupation (Herrera, 2015).

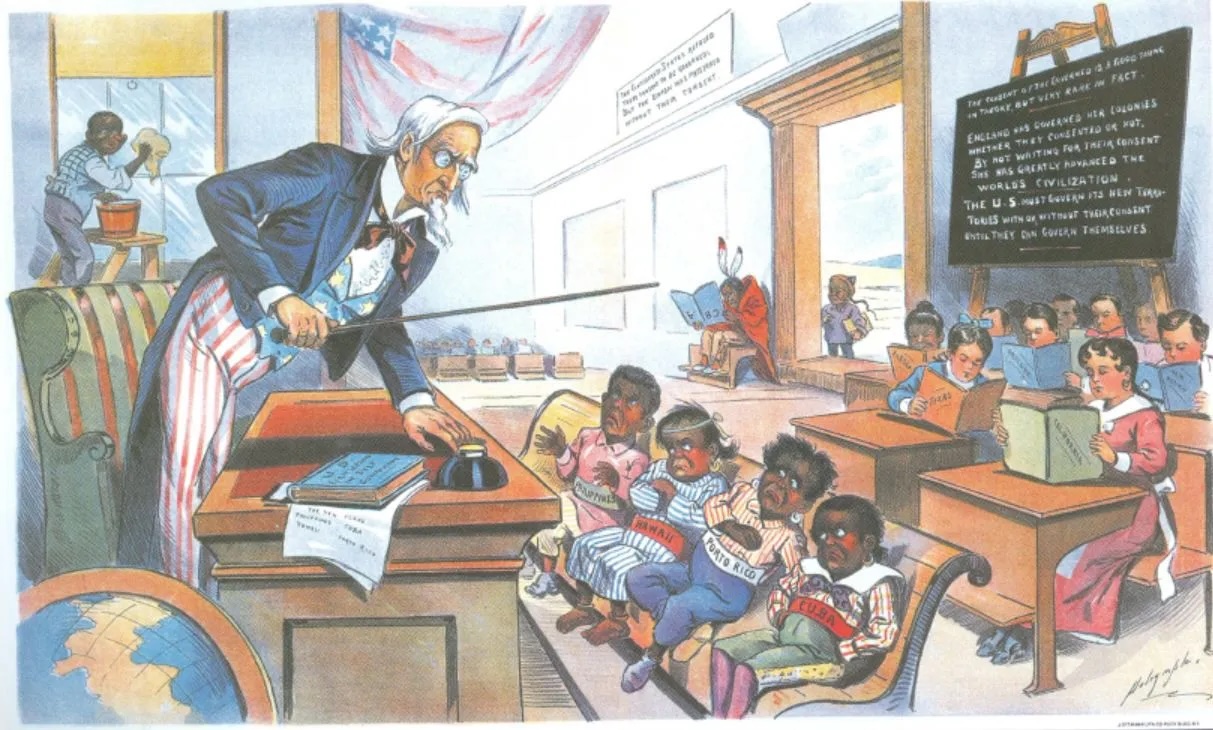

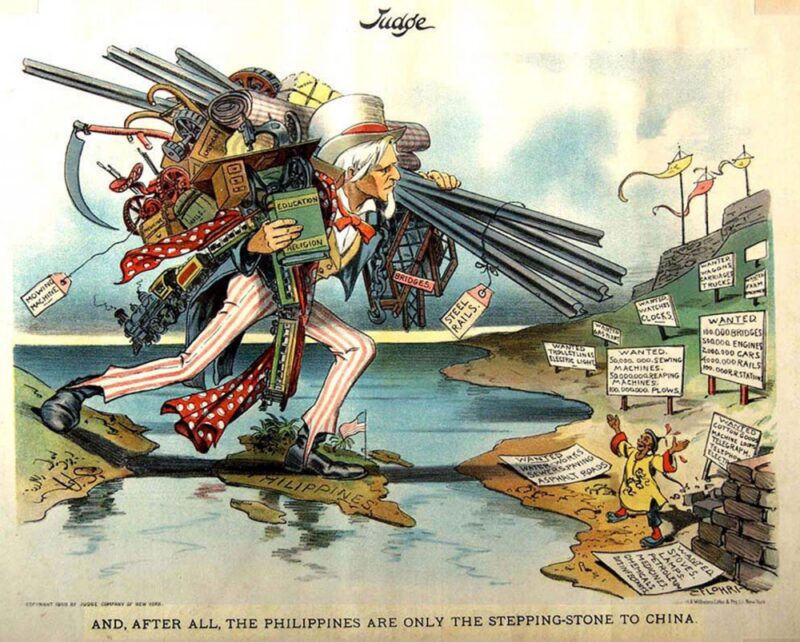

Uncle Sam, loaded with implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to get across the Pacific to China (represented by a small man with open arms), who excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. With the expansionist policy gaining greater traction, the possibility for more imperialistic missions (including to conflict-ridden China) seemed strong. The cartoon might be arguing that such endeavours are worthwhile, bringing education, technological, and other civilizing tools to a desperate people. On the other hand, it could be read as sarcastically commenting on America’s new propensity to “step” on others. “AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA,” in Judge Magazine, 1900 or 1902. Wikimedia.

Uncle Sam, loaded with implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to get across the Pacific to China (represented by a small man with open arms), who excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. With the expansionist policy gaining greater traction, the possibility for more imperialistic missions (including to conflict-ridden China) seemed strong. The cartoon might be arguing that such endeavours are worthwhile, bringing education, technological, and other civilizing tools to a desperate people. On the other hand, it could be read as sarcastically commenting on America’s new propensity to “step” on others. “AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA,” in Judge Magazine, 1900 or 1902. Wikimedia.In contrast, the American occupation following Spain’s defeat in the Spanish-American War in 1898 significantly changed the country’s linguistic patterns and revolutionized the education system. Upon arriving in the country, the Americans decided to create a public school system in the country, where every student could study for free. However, the medium of instruction was in English, given that they brought teachers from the United States (Casambre, 1982). This differed from the Spanish system in that social class and gender did not influence students’ access to education to the same extent. Furthermore, the Americans brought their own material to the country due to a lack of school textbooks. As the number of schools in the country and the pedagogical influence of American teachers increased, the perception of the Americans’ role as colonizers ultimately changed. Education became a tool to exert cultural influence, leading to the propagation of American ideals like capitalism, in addition to subverting separatist tendencies that were cropping up in the country as one colonizer was replaced by another. It also led to the suppression of knowledge concerning the US’ exploitation of the nation. Ultimately, the colonizers’ influence on the linguistic and educational landscape of the nation manifests itself in the general population’s understanding of their country’s history.

The Current History Curriculum

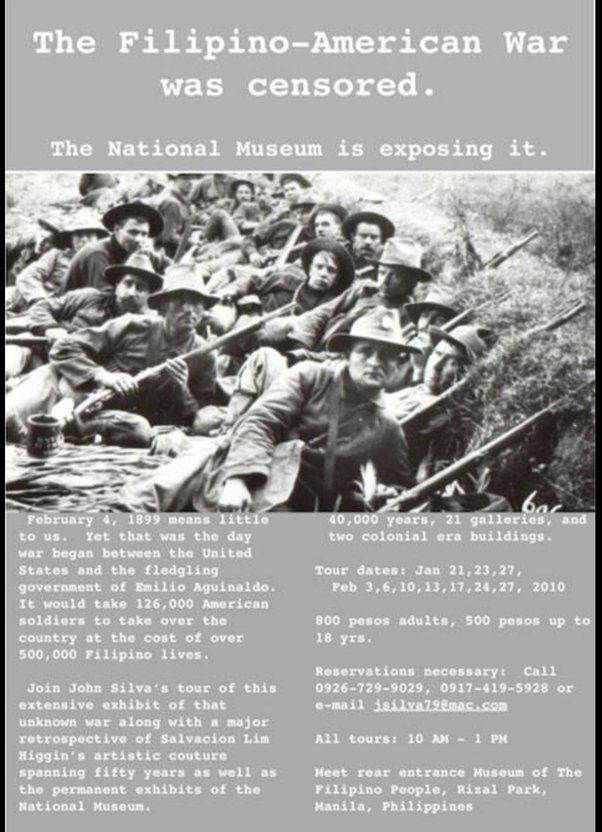

The social studies curriculum in the Philippines, called Araling Panlipunan (AP), is an interdisciplinary course that combines topics of economics and governance with history, primarily post-colonial history (“K to 12 Gabay Pangkurikulum”, 2016). The topic of World War II takes up nearly 50% of the course, while other aspects of indigenous and pre-colonial history are included to a limited extent (Candelaria, 2021). This act of prioritization is a colonial holdover. Although the Philippines indubitably played a crucial role in the Pacific Theatre during WW II, its massive presence in the AP course signals the nation’s continued alliance with the US and reinforces a mentality amongst the general public that favours it. This bias occurs as a singular American perspective is promoted by the course, wherein the actions of other countries against the Philippines are highlighted. At the same time, the exploitation of the Philippines by the Spanish and Americans is not as widely discussed. For example, although the atrocities committed by the Japanese during World War II are taught extensively as part of the curriculum, the American actions during the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), during which the Americans burned and pillaged entire villages, are not emphasized (Clem, 2016). Furthermore, it leads to the sidelining of historical events that have created the political situation in the country today, such as the issue of the current president being related to the former dictator, Ferdinand Marcos.

As the course is conducted chronologically, discussions of topics such as the Marcos Regime are left up to teachers’ discretion due to the subject’s controversial nature, given that the dictator’s son is the current president (Santos, 2022). This means that as much or as little time can be spent on it is as decided. Because of the American influence, even citizens who are taught about the atrocities that occurred during the dictatorship are not informed of the support provided to the Marcos dictatorship by the US government. During his presidency, which lasted from 1965 to 1986, the Philippines received significant economic aid from the US government in exchange for the continuation of its military presence in the country, which proved helpful to the US during the Vietnam War as it was able to utilize its bases in Subic Bay and Clark air base(Hawes, 1986). As a result of the necessity of these bases, a 1979 amendment to the 1947 Military Bases Agreement was signed, which increased the US’ fiscal contributions to security assistance. To further support this military objective, the Carter and Reagan administrations showed their diplomatic support to Marcos by visiting the Philippines and inviting him to Washington.

Additionally, when Marcos was ousted from power in 1986 by the People Power Revolution, he spent his exile in ‘Hawaii’, in the US (Southerl, 1986). Therefore, while the US is credited for introducing democratic principles to the country through its program for expanding education while occupying the archipelago, it also played a significant role in supporting a despotic government that is not as widely acknowledged. Because of this, the Filipino perception of and relationship with the US has been heavily influenced by a lack of awareness amongst the general public about its involvement in a massively corrupt administration.

Significant Developments

Despite the importance of a robust historical education in improving the public’s awareness of their own culture and geopolitical relationships, history as a subject has been transformed into a political tool in the Philippines, twisted when it can be useful and neglected when it does not support an agenda. Various bills passed in the House of Representatives (the lower house of parliament in the Philippines, below the Senate), as well as decisions taken by the Department of Education, have diminished the significance of history in the overall school curriculum and reinforced an American perspective in the historical content that continues to be taught. Department of Education Order 20, signed in 2014, removed Philippines History as a separate subject in high school (Ignacio, 2019). The argument for this decision was that Philippines History would be integrated within the broader AP social studies curriculum under different units, such as the Southeast Asian political landscape. However, educators opposing the abolition of Philippine History as a separate subject state that due to fewer contact hours being allocated for AP in total compared to English, maths, and science, it is unlikely that Philippine history can be discussed in adequate depth, considering the other social science topics mandated by the AP curriculum. In addition, House Bill 9850, which was passed in 2021, requires that no less than 50% of the subject of Philippine history centres around World War II (Candelaria, 2021). The bill’s primary concerns mention that it prioritizes the war over other formative conflicts in the nation’s history, such as the Philippine Revolution against Spain or the Philippine-American War. Furthermore, it requires modifying or reducing discussions surrounding other vital events in the Philippines, such as agrarian reforms and more recent developments like the conflict in Mindanao.

Both of these policies face significant opposition. For example, a Change.org petition demanding the return of the subject of Philippine history in high schools has garnered tens of thousands of signatures. At the same time, numerous historical experts and teachers have spoken against HB 9850 (Ignacio, 2018). Despite this resistance from academics and teaching professionals, it is unlikely that history will be prioritized unless the general public also learns to inform itself. Around 73% of the total population (approximately 85.16 million people) have access to the internet, of which over 90% are on social media (Kemp, 2023). Because of the large working population in the country, social media companies like Facebook have set up offices there. Programs that offered data-free usage in 2013 have made the Philippines a huge market for Facebook, and many Filipinos trust the news they find on the website more than some mainstream media sources (Quitzon, 2021). Even though internet access is relatively widespread, signifying that information is readily available to the average Filipino, social media, especially Facebook, often functions as a fertile breeding ground for misinformation.

Repercussions of the History Curriculum

In recent years, misinformation has become an important political tool to propagate ignorance and manipulate historical and current events to promote specific agendas. The most relevant example was the mass historical revisionism campaign leading to the 2022 general elections (Quitzon, 2021). Given that Bongbong Marcos, Ferdinand Marcos’ son, was running for president alongside vice presidential candidate Sara Duterte (former president Rodrigo Duterte’s daughter), the campaign focused on changing the public perception of both families and their period of rule. Preceding the elections, social media trolls and supporters of the campaign spread videos, doctored images, and fake news that minimized the atrocities and scale of theft that occurred throughout the Marcos regime and the Duterte administration, instead highlighting and exaggerating the perceived benefits they brought to the country. The prioritization of these political agendas is reflected in the history curriculum, as it does not sufficiently cover critical areas of Philippine history that have directly led to the political situation of today and the pre-colonial era that is an inseparable part of Filipino culture.

Recommended Policy Measures

However, another by-product of this absence of consciousness is that the general public is desensitized to poor governance and neocolonialism as their education systems and news sources constantly feed them biased and inaccurate information about the history of their own country and its relationship to others. When dictators are portrayed as good rulers and previous colonizers are portrayed as historical allies, it results in a population that unknowingly votes against its interests as they are unaware of the past events that have shaped the current political atmosphere and the various deficiencies in the system. Considering that these political campaigns rely on the general public not having a solid understanding of historical events, especially those about the martial law era, it is unlikely that politicians will take meaningful steps to improve historical education in the country since they benefit from citizens lacking awareness. As such, the onus must, unfortunately, be placed on the general public to educate themselves on good citizenship and exercise their right to vote at the grassroots level responsibly so that future local politicians and members of parliament may at least be able to encourage the study of history in the government. Additionally, teaching students how to use the internet to conduct reliable research is imperative to reduce misinformation so they can counter the misinformation they find online.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Philippine education system has been shaped by the periods of colonization the country has experienced. This has led to a history curriculum favouring the American perspective and thus disadvantages crucial elements of local history. The consequences of the lack of awareness this has caused in the general public are manifold: it has made them more susceptible to misinformation and historical revisionism. It has worked to the advantage of politicians who take advantage of it. Nevertheless, the Philippines can still reverse this trend by utilizing its high literacy rates and social media presence to promote reliable historical education. They can also push for better historical education policies through petitions and appeals to local government agencies and Senate committees related to education – such as the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the Committee on Basic Education and Culture, and the Committee on Education, Arts and Culture – amongst others (Ignacio, 2018). Overall, there are many deficiencies in the current history education system in the Philippines, but they still coexist with the potential for change. Citizens have the power to advocate and must continue using it to usher forth a more well-informed society and nation.

References

Bajpai, Prableen. “Emerging Markets: Analyzing the Philippines’s GDP.” Investopedia, 12 July 2023, www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/091815/emerging-markets-analyzing-philippines-gdp.asp#:~:text=The%20country.

Casambre, Napoleon. The Impact of American Education in the Philippines. Educational Perspectives, scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/f3bbc11f-f582-4b73-8b84-76cfd27a6f77/content#:~:text=Under%20the%20Americans%2C%20English%20was.

Clem, Andrew. “The Filipino Genocide.” Series II, vol. 21, 2016, p. 6, scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1138&context=historical-perspectives.

Constantino, Renato. “The Miseducation of the Filipino.” Journal of Contemporary Asia, vol. 1, no. 1, 1970, eaop.ucsd.edu/198/group-identity/THE%20MISEDUCATION%20OF%20THE%20FILIPINO.pdf.

Department of Education. K To12 Gabay Pangkurikulum. 2016, www.deped.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/AP-CG.pdf.

“Education Mass Media | Philippine Statistics Authority | Republic of the Philippines.” Psa.gov.ph, 28 Dec. 2019, psa.gov.ph/statistics/education-mass-media.

Gonzales, Wilkinson Daniel Wong. “Language Contact in the Philippines.” Language Ecology, vol. 1, no. 2, Dec. 2017, pp. 185–212, https://doi.org/10.1075/le.1.2.04gon.

Hawes, Gary. “United States Support for the Marcos Administration and the Pressures That Made for Change.” Contemporary Southeast Asia, vol. 8, no. 1, 1986, pp. 18–36, www.jstor.org/stable/25797880.

Herrera, Dana. “The Philippines: An Overview of the Colonial Era.” Association for Asian Studies, vol. 20, no. 1, 2015, www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/the-philippines-an-overview-of-the-colonial-era/.

Ignacio, Jamaico D. “[OPINION] The Slow Death of Philippine History in High School.” RAPPLER, 26 Oct. 2019, www.rappler.com/voices/ispeak/243058-opinion-slow-death-philippine-history-high-school/.

—. “We Seek the Return of ‘Philippine History’ in Junior High School and Senior High School.” Change.org, 19 July 2018, www.change.org/p/we-seek-the-return-of-philippine-history-in-junior-high-school-and-senior-high-school.

John Lee Candelaria. “[OPINION] The Dangers of a World War II-Centered Philippine History Subject.” RAPPLER, 20 Sept. 2021, www.rappler.com/voices/imho/opinion-dangers-world-war-2-centered-philippine-history-subject/.

Kemp, Simon. “Digital 2023: The Philippines.” DataReportal – Global Digital Insights, 9 Feb. 2023, datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-philippines#:~:text=Internet%20use%20in%20the%20Philippines.

Musa, Sajid, and Rushan Ziatdinov. “Features and Historical Aspects of the Philippines Educational System.” European Journal of Contemporary Education, vol. 2, no. 2, Dec. 2012, pp. 155–76, https://doi.org/10.13187/ejced.2012.2.155.

Quitzon, Japhet. “Social Media Misinformation and the 2022 Philippine Elections.” Center for Strategic & International Studies, 22 Nov. 2021, www.csis.org/blogs/new-perspectives-asia/social-media-misinformation-and-2022-philippine-elections.

Santos, Franz Jan. “How Philippine Education Contributed to the Return of the Marcoses.” Thediplomat.com, 23 May 2022, thediplomat.com/2022/05/how-philippine-education-contributed-to-the-return-of-the-marcoses/.

Southerl, Daniel. “A Fatigued Marcos Arrives in Hawaii.” Washington Post, 27 Feb. 1986, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/02/27/a-fatigued-marcos-arrives-in-hawaii/af0d6170-6f42-41cc-aee8-782d4c9626b9/.

Stevens, J. Nicole. “The History of the Filipino Languages.” Linguistics.byu.edu, 30 June 1999, linguistics.byu.edu/classes/Ling450ch/reports/filipino.html.

Stout, Aaron P. The Purpose and Practice of History Education: Can a Humanist Approach to Teaching History Facilitate Citizenship Education? 2019, core.ac.uk/download/pdf/275887751.pdf.

Feature Image Credit: actforum-online.medium.com Filipino Education and the Legacies of American Colonial Rule – Picture from ‘Puck’ Magazine

-

Is Singularity here?

One of the most influential figures in the field of AI, Ray Kurzweil, has famously predicted that the singularity will happen by 2045. Kurzweil’s prediction is based on his observation of exponential growth in technological advancements and the concept of “technological singularity” proposed by mathematician Vernor Vinge.

The term Singularity alludes to the moment in which artificial intelligence (AI) becomes indistinguishable from human intelligence. Ray Kurzweil, one of AI’s fathers and top apologists, predicted in 1999 that Singularity was approaching (Kurzweil, 2005). In 2011, he even provided a date for that momentous occasion: 2045 (Grossman, 2011). However, in a book in progress, initially estimated to be released in 2022 and then in 2024, he announces the arrival of Singularity for a much closer date: 2029 (Kurzweil, 2024). Last June, though, a report by The New York Times argued that Silicon Valley was confronted by the idea that Singularity had already arrived (Strifeld, 2023). Shortly after that report, in September 2023, OpenAI announced that ChatGPT could now “see, hear and speak”. That implied that generative artificial intelligence, meaning algorithms that can be used to create content, was speeding up.

Is, thus, the most decisive moment in the history of humankind materializing before our eyes? It is difficult to tell, as Singularity won’t be a big noticeable event like Kurzweil suggests when given such precise dates. It will not be a discovery of America kind of thing. On the contrary, as Kevin Kelly argues, AI’s very ubiquity allows its advances to be hidden. However, silently, its incorporation into a network of billions of users, its absorption of unlimited amounts of information and its ability to teach itself, will make it grow by leaps and bounds. And suddenly, it will have arrived (Kelly, 2017).

The grain of wheat and the chessboard

What really matters, though, is the gigantic gap that will begin taking place after its arrival. Locked in its biological prison, human intelligence will remain static at the point where it was reached, while AI shall keep advancing at exponential speed. As a matter of fact, the human brain has a limited memory capacity and a slow speed of processing information: About 10 Hertz per second (Cordeiro, 2017.) AI, on its part, will continue to double its capacity in short periods of time. This is reminiscent of the symbolic tale of the grain of wheat and the chess board, which takes place in India. According to the story, if we place one grain of wheat in the first box of the chess board, two in the second, four in the third, and the number of grains keeps doubling until reaching box number 64, the total amount of virtual grains on the board would exceed 18 trillion grains (IntoMath). The same will happen with the advance of AI.