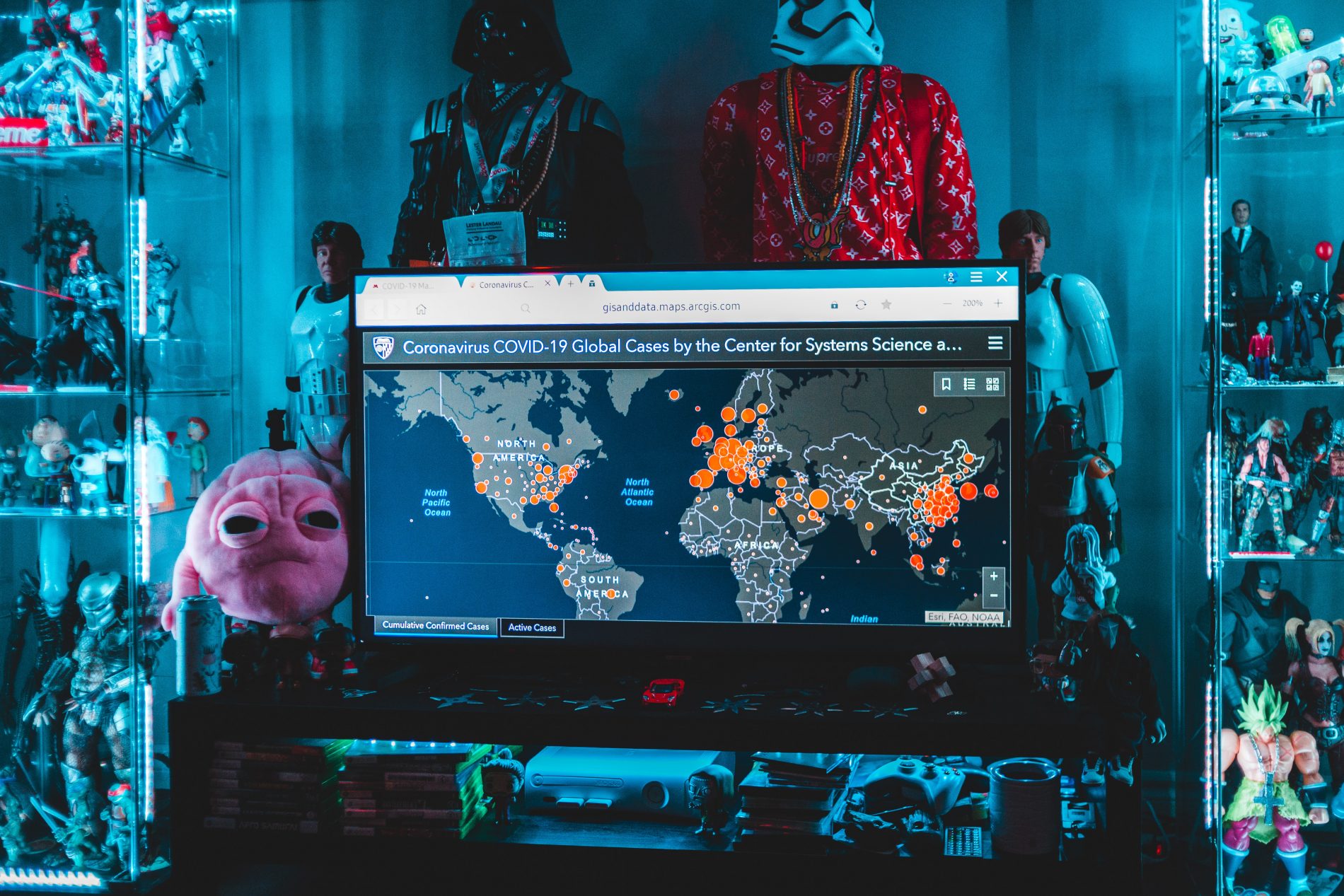

The Union budget 2020 was heavily criticized for allocating only INR 60,000 crore on the UPA flagship program, Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGA). Discontent continues even after the relief package mentioned INR 200 per person will be paid for the next three months. With 7.6 crore workers registered under MGNREGA program – around one trillion (INR) would be required to fulfill the promise. The pandemic has disrupted almost every physical activity, thereby disrupting the physical labour economy. The unfolding crisis across the country and the poor health infrastructure especially in rural areas poses a major challenge to combat the spread of the virus . According to the National Health Report, India’s government hospitals average a low figure of one bed per 1844 patients. The magnitude of the health crisis becomes apparent with the inadequacy in health infrastructure in rural India. The ongoing COVID-19 crisis is reshaping the entire global economy and is expected to be a stress test for government institutions. Even after the crisis, policy making and social programs will remain the key areas in which continuous revision must happen – to build a resilient economy in the long run. As the pandemic influenced financial crisis looms large, it is opportune to discuss public employment programs in bridging infrastructure gaps and financial losses.

Demand driven workfare programs intend to provide 100 days of employment for rural households. This scheme was launched with an objective to alleviate poverty and create public assets. Recognising the vagaries of the agriculture sector to provide stable employment, the program sought to guarantee minimum income for subsistence level labourers and also internalized short term shocks in the rural economy. In principle, the ‘right to work’ element offered a legitimate progress in public-policy discourse by empowering women and marginalized communities to work. The laudable results of the employment program have more or less achieved its social objectives by increasing individual asset creation and enhancing savings rate. Almost 50 percent of the population dependent on agriculture fall back to government employment schemes in times of labour market failure. Low productivity, inadequate modern technology, high dependence on rainfall and bottlenecks to reach the market are primary sources of such failures. Execution of public employment in India is plagued by rampant corruption and efforts to effectively implement the scheme faces hurdles and results in marginal progress. In the wake of economic slump with falling consumption in rural India and high unemployment rates, infusing cash in the hands of people is always the priority. However, marginal increase in budget allocation for public work programs has invited criticism from the economists – expecting the rural economy to struggle with slow recovery. With acute shortage of skilled labourers and an education system failing to impart quality skill education, a public employment program can be more dynamic in resolving the socio-economic and food security problems. The primary objective is to offset short term economic disturbance and smoothen consumption expenditure, but the development of the program in responding to the needs of the community is also important. Successful implementation of an employment program must factor-in convergence with other departments, quality of assets created and skill levels imparted under the program. .The three-week lockdown due to covid-19, further extended by two weeks, has exposed the inadequacy of public health infrastructure, more so in rural areas and for informal labour groups, to address their health and the resulting financial hardship. Converging the needs of villages to enhance better response during a crisis with the employment program would result in bringing accountability and creating assets.

India has experimented with a plethora of universal public programs such as Public Distribution System and Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS). In a similar vein, MGNREGS has been an important public work programme with the aim of reducing poverty and enhancing income levels. At this juncture, revising and reviewing MGNREGA scheme with the objective to reduce leakage in the system is a priority. A clear balance between the twin objective of providing employment and creating infrastructure has been missing in the literature. The gap between theoretical policy and reality has raised concern and the need to review the current approach . The obvious gap in infrastructure requirements identified during the time of crisis must converge with public programs. Such carefully designed schemes with tangible objectives will provide economic security in the short run and improve rural infrastructure in the long run.

Work completion rate can be used as a proxy for productivity because individual labour productivity is hard to ascertain with heterogeneous work projects. Although the official MGNREGA website suggests an average of 90 percent of work completion, open government data shows a decline in work completion rate from 43.8 percent in 2008-09 to 28.4 percent in 2015-16. Financial support through employment should account for both quality of assets created and the process of such creation. This would internally check and balance the operation of the scheme and intuitively bring in accountability. At present, the scheme contains the above mentioned elements but has not been used to evaluate the execution of the program. Convergence between departments to create assets and the work completion rate might explain the effectiveness of a program in physical terms.

An efficient model should enhance the skill levels of rural youth and is more than necessary to counter the loss of jobs already happening due to coronavirus lockdown. Unskilled and semi-skilled labourers will face lay-offs as industries with the recent norm on social distancing adjust to capital intensive businesses. The percentage of rural population in the age group of 15-59 receiving vocational training has reduced from 1.6 percent in 2011 to 1.5 percent in 2015-16. Unemployment rate among rural youth (15 to 29) has increased from 5 percent in 2011 to 17.4 percent in 2017-18. Although the highest unemployment rate is observed among rural females, the employability of rural youth reduces as education increases. The paradox of educated unemployment is not complex to decode, but a significant skill gap is the fundamental problem from the labour supply side. The Expanded Public Works Program (EPWP) introduced in South Africa to address the skill gap among the youth has succeeded in reducing poverty and unemployment rates. The program has been designed to create labour intensive projects not limited to infrastructure but extends to social, cultural and economic activities. The percentage of young workers under this scheme witnessed a rise from 7.73 % in 2017-18 to 10.06 % in 2019-20 in reference to the low levels of employment. This would mean the nature of the guarantee program has shifted from giving opportunities for seasonal unemployed to educated unemployed. The change is indicative of the deeper crisis faced in the rural economy and calls for a sustainable plan to use public programs as a tool to also impart skill training for the rural youth. State’s increasing dependence on work programmes to create employment needs to be revised based on community requirements. While enhancing rural employment is the immediate concern, the process of achieving it suffers from various executive problems such as corruption among government staff and individual’s lack of willingness to work. Amidst the lockdown situation due to COVID-19, unemployment will increase sharply. A well-devised strategy to address economic losses on priority and emphasis on health infrastructure through public employment must resonate in policy-making after the impact of the coronavirus crisis subsides.