Contrary to the realist belief, international states co-exist in a world order of hierarchy rather than anarchy. Ikenberry presents this hierarchical world order and the cyclical rise and fall of hegemonic powers. Early 20th century witnessed the shift from Pax-Britannica to Pax-Americana that was complete by 1945, from which point the US defended its position during the Cold War with the erstwhile USSR. It exercised its hegemonic influence even more aggressively after the Cold War. However, US dominance of the world order has been diminishing owing to the Trump administration’s isolationist approach to foreign policy, and the increasing influence of China in world politics. This article examines the catalysing effect of Covid-19 and the rise of China on the current World Order.

Trump’s policy of disregarding multilateralism and imposing its unilateralism on the world has catalysed into an involuntary retreat, protectionism, and isolationism for the USA with dire consequences for its foreign policy effectiveness.

Trump’s policy of disregarding multilateralism and imposing its unilateralism on the world has catalysed into an involuntary retreat, protectionism, and isolationism for the USA with dire consequences for its foreign policy effectiveness. The net result is that the world is witnessing an abdication of leadership by America in a world disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic. A clear pattern of isolationism can be seen in various actions of the Trump Administration since it’s assumption of the Office. In 2017, the US withdrew from the Paris Agreement, in 2018 it unilaterally reneged from the JCPOA, re-imposed sanctions on Iran and threatened sanctions on allies who supported Iran. In 2019, it withdrew troops from Syria, which led to subsequent Turkish incursion on Rojava Kurds, and in early 2020 it negotiated with the Taliban to enable withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan. With the onset of Covid19 global pandemic, the Trump administration has accused the WHO of protecting China. In a unilateral action not endorsed by its allies, USA first stopped its funding for WHO and then terminated its relationship with the UN institution. This comes as a blow to multilateralism since the US was WHO’s largest donor, contributing about $440 million yearly. In addition to this, the US has failed to provide the lead in the global response to tackle the virus despite its initiatives in the past pandemics such as H1N1, Ebola and the Zika virus. The US was absent from the WHO initiative – Global Coronavirus Response Summit (before its withdrawal from the association). In addition, the US has been unable to provide external aid to combat the virus due to domestic shortages, which explains its restraint to guide an international response in the absence of a coherent domestic plan of action. Thus, the coronavirus pandemic has acted as a catalyst in increasing the pace of US isolationism from world politics.

China has turned the tide on its previous missteps in containing the virus by publicising its governance model as the most effective way to combat the pandemic.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has established firmly China’s rise in the international stage. Though China is facing backlash for suppressing details about the virus, it is battling to overcome this criticism by providing international aid and stepping up to lead a global response using Beijing’s success as a template to overcome the novel virus. China has contributed significantly to the global response by providing materials such as ventilators, respirators, masks, protective suits and test kits to Italy, Iran, Serbia, and the whole of Africa. Grabbing its opportunities to lead international responses, China hosted Euro-Asia conference, participated in the Global Coronavirus Summit where it pledged an emergency funding of $20 million to WHO, and pledged $ 2 billion to the WHO (equalling its annual budget) to be disbursed over the next two years, thus contrasting sharply with the US behaviour of withdrawing from the WHO. China has turned the tide on its previous missteps in containing the virus by publicising its governance model as the most effective way to combat the pandemic. It continues to highlight the inadequacies and shortfalls in healthcare systems of the western world as against the success of its governance model, Beijing Consensus, and variations of it in East Asia. It is clear that China has seized the Covid-19 pandemic as a huge opportunity to establish its global leadership.

Taking advantage of the global disarray due to the pandemic, China has taken strong actions to deflect global criticism of its initial handling of the virus. Two prominent examples of this being, European Union watering down the report on Covid19 disinformation owing to pressure from Beijing, and the passing of the controversial Hong Kong security law. While the US has taken initiative in cracking down on China by repealing the special privileges to Hong Kong, other countries were cautious in retaliating against China significantly and limited their actions to sympathetic support for pro-democracy protestors. The exception to this was Britain, which offered UK citizenship to British National Overseas Passport holders in Hong Kong, despite seriously offending China. Despite the global backlash against Chinese diplomacy in the form of generous aids, international actors have expressed limited concerns through action against Chinese domination. This is due to the circumstantial mismatch in global balancing against China’s rise. The US uses unilateral actions and ‘expects’ its allies to follow, while its allies despite their serious concern over China’s rise, remain vary of following in the American footsteps. This is because US allies treat coronavirus as an immediate threat as opposed to China’s rise. The US being a status quo power is more threatened by China’s rise since it posits as a revisionist state. However, in view of China’s proactive efforts in leading global contributions to battle the coronavirus, US allies remain tolerant of China’s dominance.

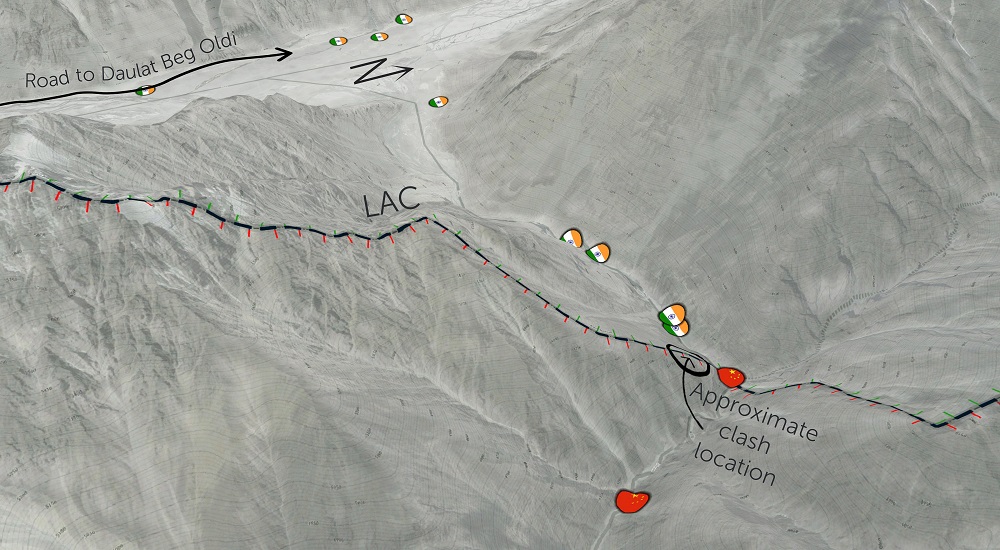

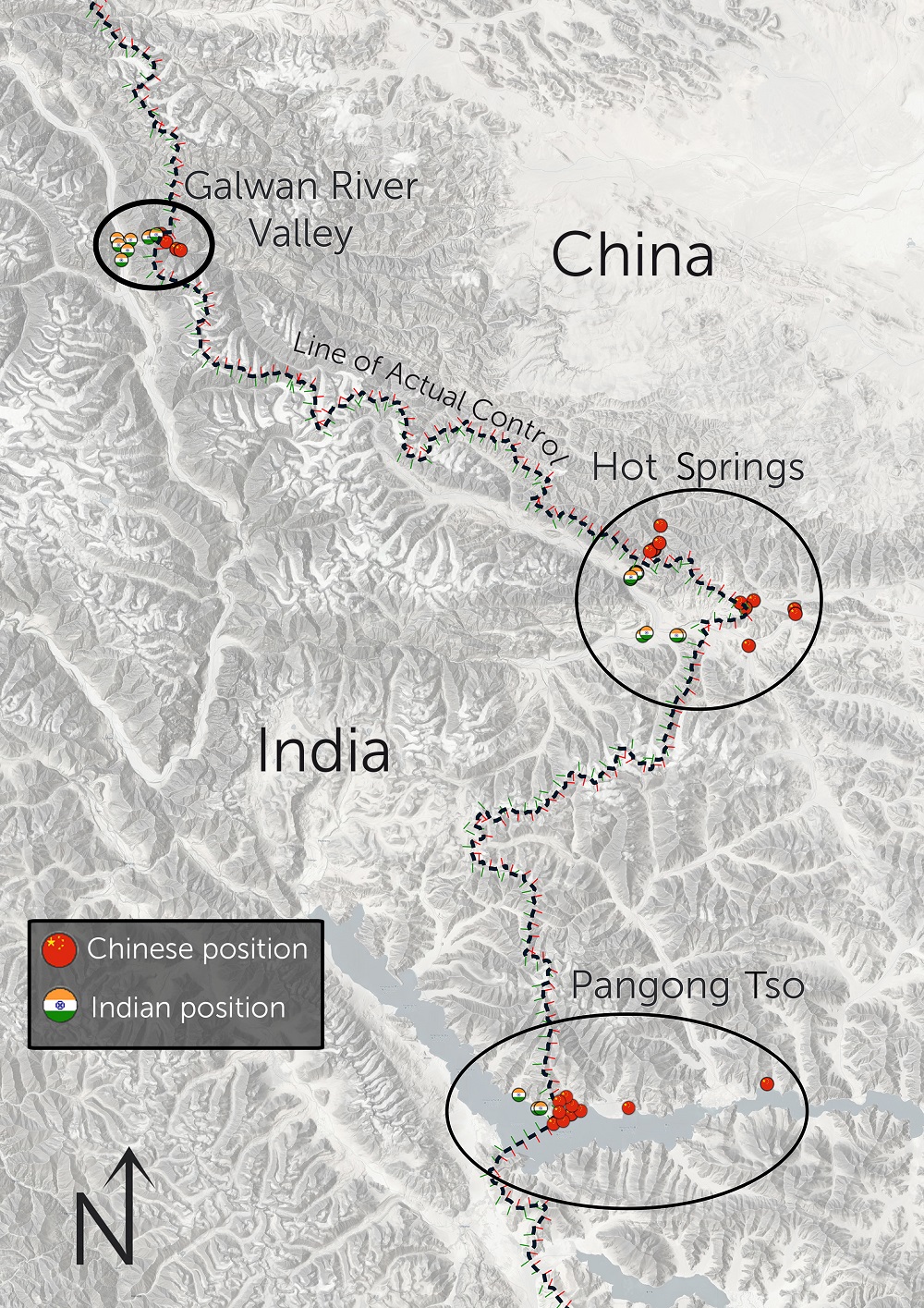

The passive and fractured response to China’s aggressive exploitation of the pandemic to establish its global leadership is a concern for India. The recent setting up of Chinese military camps in Indian controlled territory of Ladakh is a manifestation of China’s complex strategy. India has, true to its traditional policy, opted out of involving the United Statesin the ‘bilateral issue. However, it would be beneficial to be united in balancing against China’s rise. While it is necessary to work together to utilise Global Supply Chains (GSC) during the pandemic to battle the coronavirus pandemic, it is equally important to look at global balancing against China to ensure its compliance to rules-based world order. Since China’s power is derived from its economic strength, balancing strategy against China should focus on trade and economy. Chinese foreign policy depicts a pattern of economic coercion to reward or punish its counterparts. This can be tackled through concerted global action. India is, as one of the largest producer of pharmaceuticals, playing a crucial role in global efforts to fight the pandemic by providing Hydroxychloroquine globally. However, given that most raw materials are sourced from China, balancing against China requires a favourable movement of GSC diversification. US-China trade war has, encouraged companies to move production out of China and into Asian countries such as Vietnam and Taiwan. As a result of the coronavirus crisis and the global backlash, companies look to further diversify their resources and supply chains. India and other Asian countries could benefit from this if they adapt their policies suitably.

Global backlash against China’s handling of the virus in Wuhan is still a challenge for China’s geopolitical strategy. Its foreign policy is seen more as displaying aggressive and coercive approach than persuasive diplomacy.

It is difficult to estimate whether China would aspire for hegemonic leadership. Global backlash against China’s handling of the virus in Wuhan is still a challenge for China’s geopolitical strategy. Its foreign policy is seen more as displaying aggressive and coercive approach than persuasive diplomacy. Given the current volatile scenario most countries have, in the absence of US leadership, increased their dependence on China as it is now the largest provider of aid. While all this tips the scale in China’s favour, it’s hegemonic ambitions can be countered through trade strategies as its weakness stems from the fact that it is a hugely export driven economy. Global diversification of supply chains would reduce the world’s increasing dependency on Chinese manufacture and products. The world will need to be cautious as the pandemic has provided China an opportunity to tighten its grip on the global economy as the world’s workshop and technology provider. Here on, international efforts to bandwagon or balance will become a decisive factor in determining China’s rise to apex position in the world order.