Energy is crucial for a country’s growth and sustainable development. But over one-third of the world’s population, mostly consisting of people in rural areas of developing countries, do not have access to clean, affordable energy.

The climate crisis is a battle that countries have been fighting for decades now. The policies and strategies developed by different countries have helped in small ways in achieving their energy and climate goals. One strategy among all countries is the development and improvement in the use of renewables. Various studies, across different fields, have shown us the need for countries to shift to this alternative set of energy sources that will sustain life in the long run. The use of renewable energy in both urban and rural areas should be monitored and developed to achieve the sustainable development goals that countries have vowed to achieve.

Energy is crucial for a country’s growth and sustainable development. But over one-third of the world’s population, mostly consisting of people in rural areas of developing countries, do not have access to clean, affordable energy. This is an important factor contributing to the low standards of living in rural areas of developing countries.

In India, more than two-thirds of the population live in rural areas whose primary source of income is agricultural activities. But a large proportion of the rural population does not have consistent access to energy. To this population, new alternative sources of energy remain unaffordable and inaccessible due to poverty and lack of adequate infrastructure, respectively. Hence, we find that the rural populations continue to use traditional sources of energy such as coal, fuelwood, agricultural waste, animal dung, etc. Not only do these cause pollution and quick erosion of natural resources, but they impact negatively on people’s health. The need for transitioning to the use of renewable energy, especially in the country’s rural areas is of prime importance. But, to achieve this, the government must bring out policies that will guide this transition. Moreover, it is important that the government positively supports companies – both private and public – that generate the required technology and research that transforms the available renewable energy sources into energy that the public can consume.

Rural Electrification in India

The Electricity Act of 2003 enabled the building of electricity infrastructure across the rural and remote regions of the country and thus, easy access to electricity for most of the people. The Indian Government launched the Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vidyutikaran Yojana (RGGVY) in 2005, to extend electricity to all unelectrified villages. The programme focused largely on developing electrification infrastructure across villages in India and providing free connections to all rural households living below the poverty line. Further, state governments received a 90% grant from the central government which aided in extending electrification infrastructure to over one lakh villages during the period 2005–2013. Moreover, the central government worked towards increasing implementation efficiencies by engaging central PSUs in some states.

In 2015, the NDA Government launched the Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana (DDUGJY) under which, the villages that remained un-electrified under the RGGVY, were electrified. The scheme has also been significant in supporting distribution networks in rural areas, largely concerning metering distribution transformers, feeders, and consumers in rural areas (Gill, Gupta, and Palit 2019).

The central government further introduced standalone mini-grids programs, under the DDUGJY in 2016. Guided by the National mini-grid policy, State governments also contributed through various mini-grid policies to promote decentralised renewable energy solutions. Further, the Unnat Jyothi Affordable LEDs for All was introduced to encourage the efficient use of energy and under this scheme, LED bulbs were distributed to all households with a metered connection at subsidised rates. The Ujwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana was also introduced under the DDUGJY to allow a financial turnaround and operational improvement of Discoms. According to the UDAY scheme, discoms were expected to improve operational efficiency and bring AT&C losses down to 15%.

While the schemes were successfully implemented then, the rate of rural household electrification was still slow. Evaluations of the schemes found various limitations, such as high upfront connection costs, poor quality of supply, poor maintenance services, to name a few. Additionally, some states had also started initiating their electricity-access programmes to accelerate the electrification process, such as the West Bengal Rural Electrification Programme, the Har Ghar Bijli scheme in Bihar, the Bijuli Bati mobile-based app to enable last-mile connectivity and household connections in Odisha (Gill, Gupta, and Palit 2019). To address this issue, the central government then launched the Pradhan Mantri Sahaj Bijli Har Ghar Yojana (PM Saubhagya) in September 2017, with the ambitious target of providing electricity connections to all un-electrified rural households by March 2019. Under this scheme, the government has electrified all of 597,464 census villages in the country (Bhaskar 2019).

Barriers to adopting Renewable Energy in Rural Areas

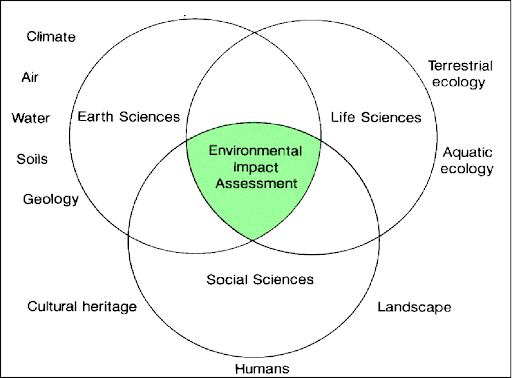

This section focuses on the issues that restrict the efficient adaptation of renewable energy in rural areas. As the government continues to promote renewable energy in rural communities, it should keep in mind these following limitations and develop mechanisms to overcome them as and when they arise. While employing renewables to supply electricity, the problem of grid integration arises. Most electricity grids and the technology used, are designed and placed around fossil fuels. However, when they transition now to more non-conventional forms of energy such as wind and solar, the designs and placements of power generation systems have to change rapidly. Thus, heavy emphasis should be placed on improving the research and infrastructure required to make this transition as smooth as possible. That is, the government should research the most optimal locations for wind turbines and solar panels, as not all lands in rural areas can be employed for this purpose. Otherwise, it may negatively impact the quality of agricultural lands. Upon conducting the required research, the infrastructure to connect all areas to the electricity grids must be developed and well-financed by the government to satisfy the energy demands of the rural population. For instance, in Germany, while the wind power potential is in the northern regions, major demand for it is in the southern region. Thus, the country’s energy transition process emphasizes upgrading the electricity grid infrastructure that would make it possible for power to flow from north to south (UNCTAD 2019). Further, the planning should also focus on balancing the energy mix in the power grid. The transition to renewables will not be a quick one, which implies that for the short term the power grid will be a mix of different sources of energy. Thus, the plans should design the grids in such a way that the proportion of each energy source balances one another so that there is no leakage or wastage in the system, especially given the fact that energy storage technology is still underdeveloped in the country.

For many years now, there has been an emphasis on the potential of decentralised electricity comprising off-grid or mini-grid systems to help with rural electrification. The government introduced a national mini-grid policy in 2016 to promote decentralised renewable energy. With the increase in the use of solar energy, solar-powered mini-grid systems were found to be more economical and accessible to rural households (Comello et al. 2016). These systems could substantially improve the people’s standard of living and eliminate the use of harmful fuels such as kerosene oil for simple household appliances such as lamps and cooking stoves. However, an IEA report found evidence that this potential is limited, and would not be beneficial for large, productive, income-generating activities. Thus, mini-grids are often considered a temporary solution, until grid connectivity is achieved (IEA 2017).

Whether a grid system or an off-grid system is implemented, high connection charges will automatically limit the rural population’s ability to connect to the grid.

A major challenge that the government must keep in mind is affordability. Whether a grid system or an off-grid system is implemented, high connection charges will automatically limit the rural population’s ability to connect to the grid. On the one hand, better access to electricity will increase productivity and lead to the growth and development in the region but on the other hand, most of the rural communities live below the poverty line and will not be able to afford the connection, even if they have access to it. While decentralised energy sounds economical and sounds like an obvious solution, it is also limited in capacity.

Another factor that the government must keep in mind for the adaptation of renewable energy in rural areas is the situation of state and private distribution companies (discoms) in India that play a pivotal role in the rural electrification process. While the government set the goals and adopted a strategy to electrify all rural households under the Saubhagya scheme, it was the discoms’ responsibility to implement these strategies and achieve the goals. A TERI report found that the discoms had difficulty carrying out the electrification process because the strategy adopted by the government had not considered the difference in demographics in the rural areas (Gill, Gupta, and Palit 2019). That is, each area differs in population size, density, and topography and the discoms found it hard to implement a similar strategy to all places alike. Moreover, the financial status of many state-run discoms has been stressed over the past year due to increasing losses and lack of adequate support from the respective State governments. Over the past year, dues to power generators have increased to Rs 1.27 trillion (Economic Times 2021). The annual 2021 budget’s outlay of over Rs 3 trillion, to be spent over five years, to improve the viability of state-run discoms, is a step in the right direction. The TERI report also found that discoms face institutional burdens in the electrification process (Gill, Gupta, and Palit 2019). The companies are most often strapped for time and must deal with huge amounts of paperwork. Simultaneously, they have to be physically present to install the necessary infrastructure and manage the labour employed in different states. In the end, it remains to be seen how the discoms will manage to monitor and review the electricity infrastructure in the rural areas, especially given the huge amounts of debt that they are trapped in.

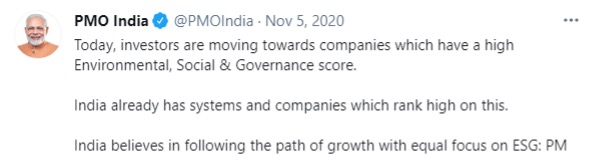

The government must also work towards increasing and incentivising private sector participation. While the private companies were interested in taking up tenders for the production of electricity through renewable energy sources in the past, the recent withdrawal of benefits such as accelerated depreciation has been a cause for concern. Companies like Suzlon Energy Ltd. face lower returns on their investment, thus deterring them from investing in future projects. Removal of benefits also discourages smaller companies that are looking to invest in this sector as it increases not only the cost but uncertainty about the government’s policies. Companies will refrain from investing if they do not anticipate a high return in the future. For grid connection systems to be successful and efficient in the long term, the government must ensure a strong governance structure, and a stable and enabling policy environment that constantly encourages fresh private sector participation. Concerning the rural electrification process, the government must encourage private sector participation because it would complement the public sector companies thus sharing the burden of production, installations, and technology as well as the process of maintenance and regular checks once the grid connection is complete.

A shift to renewable energy in rural areas will no doubt have a positive impact on the health and well-being of the population. It will also improve the standard of living and in most cases, the productivity of the people. But the change has to be a gradual process. Even if renewable energy and electricity are affordable and accessible to the people, alternative cooking fuels and technology will take time to be accepted in practice as they may not have the same performance quality as traditional stoves and appliances that the people are used to. To overcome this hurdle, the government must ensure that the policies formed will guide the adjustment to renewables for many years to come. Moreover, the government must spread knowledge and awareness about the benefits of shifting to appliances that are sourced through renewable sources of energy. Besides, some rural households collect firewood for not just individual consumption but also to sell it (IEA 2017). This is a source of income for these households hence, the government should tread carefully when they implement programs that seek to reduce the collection and use of firewood. For years now, the government has promoted and subsidised the use of LPG within rural communities, as an alternative for other harmful sources of energy. While it has helped improve people’s health to some extent, it would be beneficial for the government to gradually nudge the decrease in the use of LPG and increase the use of renewable alternatives. Apart from the definite benefits to the environment, such a change would serve to reduce the rural-urban energy gap in India.

The shift to renewable energy sources holds huge amounts of risks and uncertainty. But, despite this, there is a need to make long-term, accurate forecasts of energy demand and develop drafts of policies beforehand that would guide the process of supplying energy to satisfy the demand. Energy supply projects necessitate this because they have long gestation and implementation periods. With the climate crisis advancing rapidly, it would serve the government well to be prepared.

International Collaboration

International cooperation can play a crucial role in expanding the distribution of renewables. It can help countries benefit from shared infrastructure, technology, and lessons. The challenge thus lies in designing policies that will facilitate this technology and infrastructure transfer, especially in countries where the renewable energy sector is emerging. International organizations such as the Commission on Science and Technology for Development can play an important role in supporting such collaborations. Policies should also facilitate mechanisms that will help improve the current capabilities in developing countries.

For instance, the Indo-German Energy Programme – Access to Energy in Rural Areas was signed to create a favourable environment for rural renewable energy enterprises so that they can provide easily accessible energy services to the rural population.

The bilateral collaboration brought in local and international professional expertise to support private sector development, to identify and improve viable sources of finance, and to help design government schemes to achieve sustainable energy security and provide clean cooking energy solutions to the rural population. The GIZ – the German Corporation for International Cooperation – worked closely with India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) to successfully implement the program. The program succeeded in training more than 10,000 professionals to qualify as energy auditors. It has also helped increase private sector investment and develop a calculation to determine the CO2 emissions for the Indian electricity supply grid.

Way Forward

Research and innovation are essential to improve renewable options for producing clean cooking fuel. There is also a need for location-based research to produce appropriate workable technologies. Long-term policies and outcomes are important to consider. So, conducting significant research will not only help understand the present conditions but will also help policymakers make informed decisions in the future. It is also important to educate and communicate to the rural population about the relative advantages of using modern energy sources over traditional sources. For instance, consumers may be unaware of the health impacts of using traditional sources of energy for cooking. Moreover, they may distrust conventional alternatives due to their unfamiliarity with them. Thus, the responsibility falls on the government to properly inform them of the need for the shift to renewables and curb the spread of misinformation.

Further, alternative solutions will only succeed if they are established in cooperation with the local users. “The women in rural areas play an important role when it comes to energy transition” (IEA 2017). Several initiatives such as the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves, SEforALL, and ECOWAS address the joint issues of gender empowerment, energy poverty, health, and climate (IEA 2017). Training and capacity building are key to the shift to renewable sources of power. And in rural energy applications, this can be improved by taking into account the gender issues that plague society. There is a high possibility that rural engineers, once trained, might migrate to urban areas in search of more lucrative work. In response to this, the Barefoot College International Solar Training Programme takes a different approach to capacity-building in rural areas and trains the grandmothers in villages who are more certain to stay and help develop the community.

a shift to clean energy in rural areas that houses the section of the population that lives below the poverty line will be more successful if it is seen as a strategy to broaden community development.

Thus, a shift to clean energy in rural areas that houses the section of the population that lives below the poverty line will be more successful if it is seen as a strategy to broaden community development. This includes higher employment, better infrastructure, roads, and telecommunications. This process requires careful design of policies and the establishment of a supportive environment that includes not just innovative business models but also maintenance systems that will sustain the development in the long run.

Conclusion

To summarize, rural electrification and the transition to renewable energy in rural areas have been a part of the government’s agenda for many years now, irrespective of the ruling party at the centre. Necessary policies have been introduced to guide the process. While it is great that the government recently achieved universal electrification, it remains to be seen whether the quality of power provided to these villages meets the needs of the population. Further, in this process, state-owned discoms have taken a serious financial hit and it is a tough road to recovery from here. Adding on, the COVID pandemic has slowed down the development and recovery of these discoms. The government should first increase budget outlays in the following years and create a system to monitor the use of these finances. Second, it could turn to privatisation. Privatising discoms on a larger scale would reduce the financial and risk burden on the government and ensure efficient functioning of the companies. Additionally, it is important that while policies are being designed, the deciding parties have a complete understanding of the socio-economic situation of the communities within which they will make changes. To do this, experts who have studied the layout of these rural areas extensively should be involved in the process, along with leaders from the respective districts who are bound to be more aware of the situation and the problems in their areas. More importantly, the government should keep the process of the transition to alternative energy sources transparent and keep an open line of communication with the rural population to earn their trust before they make significant changes. Finally, India is one of the largest consumers of different renewable sources of energy. While it is important to make changes to the policies in this sector, it is also imperative that the government tries to maintain stability in policies that support the companies which help satisfy the growing energy demand in the country.

References

- Bhaskar, Utpal. 2019. “All villages electrified, but last-mile supply a challenge.” mint, December 29, 2019. https://www.livemint.com/industry/energy/all-villages-electrified-but-last-mile-supply-a-challenge-11577642738875.html.

- Comello, Stephen D., Stefan J. Reichelstein, Anshuman Sahoo, and Tobias S. Schmidt. 2016. “Enabling Mini-grid Development in Rural India.” Stanford University. https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/IndiaMinigrid_Working_Paper2.pdf

- Economic Times. 2021. “Discom debt at Rs 6 trillion; negative outlook on power distribution: ICRA.” The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/energy/power/discom-debt-at-rs-6-trillion-negative-outlook-on-power-distribution-icra/articleshow/81431574.cms?from=mdr.

- Gill, Bigsna, Astha Gupta, and Debajit Palit. 2019. “Rural Electrification: Impact on Distribution Companies in India.” The Energy and Resources Institute. https://www.teriin.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/DUF%20Report.pdf.

- IEA. 2017. “Energy Access Outlook: From Poverty to Prosperity.” International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-access-outlook-2017.

- UNCTAD. 2019. “The Role of Science, Technology and Innovation in Promoting Renewable Energy by 2030.” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/dtlstict2019d2_en.pdf.

Feature Image: The Better India

Image 1: www.alliancemagazine.org

Image 2: indiaclimatedialogue.net