Abstract

The Indian Political climate is always one of enormous diversity and vibrancy. In recent times it has tended to become politically charged with extreme ideologies. In 2014, the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power with a landmark majority, which it sustained in the following 2019 general elections. In the time that the Bhartiya Janata Party has been in power, there have been popular protests and reports that give rise to apprehensions that the democratic practices of India are in serious decline. This paper analyses whether the government led by the BJP is functioning more as a majoritarian entity that disregards democratic norms. In doing so it aims to answer the primary question of whether there is erosion in adherence to constitutional mechanisms in policymaking and carries out a review of the educational realm with regards to allegations of bypassing democratic and constitutional norms. The research is based on primary and secondary sources and mixed methodology: collation and analysis are based on already existing data with a mixed focus on quantitative and qualitative aspects. For the former, numerical data has been gathered from official government sites while the latter is drawn from pre-existing literature, published research papers and journal articles. The paper concludes by affirming the thesis and supports the argument that anti-democratic trends are indeed present in the Indian Governmental apparatus.

Introduction

Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power gaining a spectacular single-party majority in the general elections of 2014, the first in nearly three decades (Jaffrelot, 2019). This success was replicated in the Lok Sabha elections of 2019 which marked two full consecutive terms of the BJP regime for the first time. This is also the first time in nearly three decades that a single-party majority government is in power since 2014.

India is, for long, seen as the World’s largest Democracy. Although this is a well-known tag bestowed to India, with the vast diversity of thought, ideologies and practices adopted by different governments there have been times in Indian political history where the actions of governments do not align with the overarching democratic values at large.

A relevant instance of the same is the 1975 declaration of Emergency under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Dubbed as one of the darkest times of Indian democracy, this period witnessed civil liberties being harrowingly curbed and journalistic freedom and opposition faced a draconian crackdown. Gyan Prakash, a historian and a scholar, reflects upon this event under Congress rule in a way that has significance when analysing the political happenings of contemporary times. The essence of his work is that the Emergency was brought on by a larger reason than an individual’s quest for power (Prakash, 2019); he asserts that Indian democracy’s strained relationship with popular politics is to blame. There is then merit in assessing how Indian Democracy may be vulnerable to subversion and the extent to which structural issues in the democratic framework are being exploited currently by the BJP, the party in power.

The decline in adhering to Democratic norms under the BJP Rule

In the recent past, three international reports have suggested that the democratic nature of the Indian nation-state is on a decline.

Freedom House, a non-profit think tank located in the United States, downgraded India from a free democracy to a “somewhat free democracy” in its annual report on worldwide political rights and liberties. The V-Dem Institute, based in Sweden, in its most recent study on democracy, claimed that India has devolved into an “electoral autocracy. Additionally, India fell two spots to 53rd place in The Economist Intelligence Unit’s recent Democracy Index (Biswas, 2021).

These reports, however, are of international origins and subject to an ethnocentric view of what constitutes democracy and democratic practices. Although they are worth mentioning, their evaluation cannot be fully accepted at face value.

The sentiments of this report however do find echoes on the national front. A recent event wherein the ruling government was criticised internally for showcasing a lack of democratic conduct was with regards to the new National Education Policy.

National Education Policy 2020 was unveiled on July 30, 2020. In 2017, the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) formed a committee chaired by Dr K. Kasturirangan (former chairman of ISRO) to review the existing education policy and submit a new proposal (Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, 2020). The committee circulated a draught NEP for public comment in the year 2019, the edited version of the same is expected to replace the decades-old 1986 Policy on Education.

Some key features of the NEP 2020 include restructuring and reform of school curriculum, changes to curriculum content, the aim to achieve foundational literacy, and ensure that the children who enrol in schools are retained in the system and finish their schooling rather than dropping out and more (Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, 2020) .

The reforms and restructuring that the NEP suggests have the potential to elevate India to the status of a desirable educational hub. It offers a welcome and refreshing change from the rote learning patterns and administrative limitations that have so far dominated the educational realm.

The policy thus cannot be denied credit where it is due. There are, however, some strong critiques levelled against the NEP by scholars, educators, opposition and students alike. The nature of these critiques signals the idea that some anti-democratic elements underlie the policy and its construction.

The first of these criticisms is against the centralisation of education while the second criticism concerns itself with the lack of commitment to a secular curriculum. The Constitution had mandated education as a state subject, which was later amended to make it a concurrent subject thus bringing in a stronger role for the Union government. This amendment is seen as a blow to the federal structure of the country. The NEP is fully dominated by the Centre thus making the states mere bystanders.

Opposition ruled states have questioned the need for the NEP to take effect during the Covid 19 pandemic and levelled a range of accusations. The Delhi Education Minister stated that the NEP lacks mention of the government-run school system and that he believes the policy will pave the way to privatize education, which is a concern as it will create a situation where not all can have access to high-quality education. The Chhattisgarh chief minister commented along similar lines alleging that the fine print of the NEP displayed no space for state concerns nor any tangible improvement in educational quality. In Rajasthan, a three-member committee was formed to analyse and evaluate the NEP, working off their findings Rajasthan’s Education minister expressed concern regarding the funding of the policy and raised the question of lack of clarity regarding the 6% GDP being attributed to the educational realm (Sharma, 2020).

The contention regarding NEP also stems from the fact that Education is on the concurrent list. The Sarkaria commission, set up in 1983 by the central government stated that to pass a law on a concurrent list subject, the union government should ensure that the states have been adequately brought into the folds of discussion and weight is given to their opinions during consultation. The NEP 2020 is, however, not a law and is a policy, therefore it does not fully fit into the ambit of this suggestion. It is perhaps the content of the policy that has created furore from the states regarding not being adequately consulted (Menon, 2020).

The educational sector is one where the states have had tremendous sway and many practicalities fall within the state jurisdiction, additionally, 75-80 per cent of the expenditure is accounted for by the state (Jha, 2019).

The NEP in contrast to previous national policies was approved by the Union Cabinet and did not go through the parliament. Thus, the level to which states accept it and subsequently the larger question of how well Indian federalism is operating comes under scrutiny.

Prior to the 42nd Amendment in 1976- Education remained on the state list. Through an amendment made in 1976 to Schedule VII of the constitution, education was shifted to the concurrent list upon the recommendation of the Swaran Singh Committee. This move was regarded as an avenue to empower the centre with centralised policymaking advantages.

Some experts find parallels between the dark Era of Democracy, the period of emergency under Indira Gandhi, and the current government under the BJP. The 1976 provisions under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi saw the transfer of five state subjects to the concurrent list, including the education sector. This has been identified as the foundation on which NEP stands and thereby has been interpreted as having a basis that does not align with constitutional democratic values (Raveendhren, 2020).

The relationship between the States and the Union government concerning all educational policies from the eve of independence until the NEP 2020 has undergone noticeable changes. NEP 1968 gave a primary role to the state while the union government committed to assisting states (Menon, 2020). On the other hand NEP 1986, in the aftermath of the Emergency and on the recommendation of the Sarkaria committee, put forth a vision for partnership between the union and the states. NEP 2020, mentions neither of these, assumed to have taken the approval of the states for granted.

The second major critique of NEP that implies an anti-democratic approach brings to the forefront the proposed curricula for moral values. The Indian Nation state adopted a form of secularism that rested on the strategy of non-interference. This form of secularism espouses that the state and religion are not completely and wholly separated. Instead, it proposes an equidistance of the state from all religions and accordance of equal respect to them without favour or priority being given to one over another.

One of the ways in which the ideal of Indian secularism is affirmed is through the education system. According to article 28 of the Indian constitution Governmental educational institutes in India do not permit the dissemination of religious instruction, however, they do not prohibit religious text or books from being used in the classroom (Gowda C. , 2019). This is most often noticeable in the literature curriculum where devotional poetry is present. Tulsidas, Kabir to Malik Muhammad Jayasi to even John Henry Newman are all often included and studied. The inclusion of various religious poets and works from a variety of religions reflects the attempt made by the Indian educational system to embody the constitutional ideal of secularism. It is of course debatable and subject to change the extent to which each school adheres to upholding this secular and diverse teaching, although there is a commitment to the ideal, nonetheless.

The second critique against NEP can be understood against this background. In a section termed inspiring lessons from the literature and people of India, stories of Panchatantra, Jataka, Hitopadesha etc are mentioned. Critics assert that these stories come from an unequivocal Hindu background and a secular curriculum should ideally have included Aesop’s Stories and Arabian Nights as an equal part of Indian folklore.

They emphasize the importance of this measure to ensure that all students, no matter their faith feel represented and included in the classroom and the moral imagination of pupils are shaped to respect diversity and tolerance.

Education: Policy Changes in Academia

The NEP controversy hints at some concerns in the larger system of education. The BJP government which has been in power since 2014 has enacted several policies, laws and acts, and much like all governments has garnered appreciation and criticism alike. It is the content of the critical claims that warrant discussion, for much of the disapproval claims that democratic and secular ideals of the Indian nation are being cast aside.

A recent contention arose due to the decision of CBSE to reduce the curriculum to alleviate student pressure on the line forum. The Central Board of Secondary Education announced a 30 per cent reduction in the curriculum. One of the concerns is that under this provision, chapters on federalism, secularism, democratic rights need not be taught in class 12 (Sanghera, 2020). Class 10 political science syllabus also saw the removal of chapters such as “popular struggles and movements” and “democracy and diversity”.

These omissions have invited considerable disapproval from scholars and experts across fields. The former director of the National Council of Education Research and Training commented that the cuts have rendered some remaining topics “incomprehensible”. Educators on the ground state discontent with the removal of topics for they believe it to promote self-reflection and criticality (Sanghera, 2020).

The rewriting of textbooks has persisted at state levels before the 2014 elections and is not a novel phenomenon. In BJP ruled states it can be noted that a counter idea of history is underway in educational texts. In this exercise, some ideologically conservative Hindu organisations have been accorded more space and appreciation for their contributions, however, the educational attention accorded to ideals of secularism and so forth has been minimized.

In Gujrat for instance as far back as 2000, there was a move that made it compulsory for teachers to attend Sanskrit training camps in preparation for when the subject would be made mandatory.

The focus on the educational sphere and the changes that occur in it are of significance because the policies of the state in such realms are not divorced from the Indian climate and foster a culture of tolerance at large.

In recent times, experts have raised some concerns regarding the qualifications of those in high governmental positions. The Prime Minister of the country stated his belief regarding the roots of cosmetic surgery and reproductive advancements of modern times as having already existed in ancient India (Rahman, 2014). Drawing upon the Sanskrit epic of Mahabharata, he spoke of genetic science as an explanation for the birth of Karna and cosmetic surgery as an explanation for the physique of Ganesha- an elephant-headed Hindu God. The Minister of Science and technology in 2018 stated at the 105th edition of the Indian Science Congress, that Stephen Hawking went on record to assert that the Vedas, a body of Indian scripture, had a theory that superseded Einstein’s famous E=mc2 theory of relativity (Koshy, 2018).

In contrast, the first National Democratic Alliance headed by Atal Bihari Vajpayee demonstrated an affinity for learning and scientific rigour. M.M. Joshi, the Human Resource Development Minister for instance had completed a doctorate in physics. George Fernandes, Yashwant Sinha and Lk Advani are among some other examples of cabinet ministers who were profoundly involved with academia on public policy and history. Some members of the government such as Jaswant Singh and Arun Shourie also authored some works (Guha, 2019).

Since it is noticeable that some policies of the ruling government have garnered critique, perhaps the logical next step is to evaluate the process of policymaking as it has shaped up in the last 7 years.

Institutional norms and parliamentary procedures in India, especially for legislation making are designed to ensure space for debate, discussion and dissent. This operates as a system where all decisions are subjected to scrutiny by the people’s representatives. To that end, adherence to parliamentary procedure is an indicator of a government’s treatment of and respect for democracy. To carry out any analysis of this sort in an objective manner, one must first ascertain what exactly constitutes an ideal parliamentary procedure.

Parliamentary Procedure on Legislation Making: How Does A Bill Become An Act?

Acts usually start as bills which simply put, is the draft of a legislative proposal. This bill may be introduced by public members or private members and requires passing in the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha as well as the president’s assent to become a law.

There are (Lok Sabha Secretariate, 2014) three stages through which a bill is passed in the parliament: these are known as the first, second and third reading respectively.

For the First Reading, the speaker puts forth the request for leave of the house, which if granted is used to introduce the bill. Following this stage is the second reading which entails general discussion. It is during this stage that the House may choose to refer the bill to a parliamentary committee for further input or even circulate it to gauge public opinion. During the second reading, parliamentary procedure states that a clause-by-clause reading must proceed, and it is during this time amendments are moved. The second reading concludes with the adoption of ‘Enacting Formula’ and ‘Long Title of the Bill’. The next stage is the third and the last reading. At this Juncture, debates for and against the bill take place. For an ordinary bill, only a simple majority of the members present, and voting suffices, however for a constitutional amendment bill, in keeping with article 368 of the constitution, a majority of the house’s total members and at least 2/3rd members present, and voting is deemed necessary. Once this process is complete, the bill is sent to the other house of the parliament and goes through the same stages after which is referred to the president for his assent.

Analysis of Parliamentary Procedure under the BJP Government

With the great furore over the recent Monsoon session of the parliament, opposition leaders and journalists have expressed dissatisfaction with the government’s treatment of parliamentary procedure.

The monsoon session of the parliament is one example where a couple of mechanisms that have increasingly been used as of late signify a subversion of the democratic process (Brien, Autocratic Government doesn’t want Parliament to Function, 2021).

The first of these is the misuse of Article 123 also known as the Ordinance Route. Article 123 of the constitution permits the president to enact a temporary law in the event of urgent and unavoidable circumstances.

During the first 30 years of our parliamentary democracy, for every 10 bills in the parliament, one ordinance was issued. In the following 30 years, this number went to 2 ordinances per every 10 bills. In the BJP Government’s first term from 2014-2019, this number went up to 3.5 ordinances per every ten bills. For perspective, while 61 ordinances were issued under the UPA government spanning ten years the BJP-led NDA government issued 76 ordinances in a time frame of 7 years spanning from May 2014 to April 2021. It is also useful to note that ten of these ordinances were issued right before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections (Gowda M. R., 2021).

As many as 11 ordinances have been passed since March 24th, 2020, which is when the lockdown was imposed. Five of these relate to covid 19, two to the health sector, every other ordinance such as the Banking Regulation Amendment and the Agriculture bills do not have anything to do with the coronavirus pandemic (Brien, The ordinance raj of the Bharatiya Janata Party, 2020).

Another practice that raises serious concern relates to the issue of repromulagation. However, it is important to note that the recourse to ordinance route and repromulgation is not an exclusively BJP action. Before the year 1986, no central government was known to have issued a repromulagation and this method came into view during the Narasimha Rao government in 1992. This was the landmark time frame that one can trace the trends of repromulagation as originating from.

As far as the ordinances are concerned, they are an emergency provision, however, many governments have used them with an almost immoral frequency (Dam, 2015). According to PRS Legislative Research’s reports, average ordinances issued could be placed at around 7.1 per year in the 1950’s while in the 1990s there was a marked increase to an average of 19.6 per year. The 2010s witnessed a dip in the trend with an average number of ordinances being 7.9 per year (Madhvan, The Ordinance route is bad, repromulgation is worse, 2021). This number has unfortunately risen again in recent years with an average number of ordinances numbering 16 in 2019 and 15 in 2020.

The issue of repromulagation of ordinances was brought up in the Supreme Court and was deemed as an unconstitutional practice in January of 2017 by a bench of seven judges. This judgement decisively stated that repromulagation of ordinances was an unconstitutional practice that sought to subvert the constitutionally prescribed legislative processes (Madhvan, The Ordinance route is bad, repromulgation is worse, 2021).

States have also used ordinances to pass legislation. A non-BJP ruled state Kerala, for example, published 81 regulations in 2020, whereas Karnataka issued 24, and Maharashtra issued 21. Kerala has also re-promulgated ordinances: between January 2020 and February 2021, one ordinance to establish a Kerala University of Digital Sciences, Innovation, and Technology was repromulgated five times (Madhvan, The Ordinance route is bad, repromulgation is worse, 2021).

Although previous administrations and other states have utilized ordinances to undermine the constitutional process, the problem is decidedly amplified under the present rule with regards to the number of ordinances produced per given period.

This sort of rise in ordinances being issued points to a trend of avoiding in-depth critical evaluation and discussion on proposals by rushing them into becoming acts.

One of the most controversial ordinances in the recent past pertains to the three farm laws which now stand repealed after year-long demonstrations and protests at the Singhur border by farmers. The reason for not introducing these proposals in the parliament and instead enacting ordinances is unclear for there seems to be no urgent link to the covid 19 pandemic. Additionally, the farm bills not being subjected to any discussions nor being referred to parliamentary committees for any further report making has led to removing any possibility for amendment. These laws provide a useful avenue to assess why the bill was not passed through a proper parliamentary process and instead rushed through the ordinance. This assumes critical relevance since agriculture is essentially a state subject, and the States were not consulted on the farm laws.

The ordinance culture has also extended to BJP run states, for instance, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat adopted ordinances weakening labour laws without consulting workers’ unions or civil rights organisations during the lockdown. Moreover, this was followed up on 15th March 2020, when colonial-era legislation was enacted as an Ordinance. This was the Uttar Pradesh Recovery of Damages to Public and Private Property ordinance which would heavily fine any damage to property, public or private during a protest.

Under the BJP-led NDA rule, there has been slim or no involvement of parliamentary committees. Parliamentary committees are key in assessing a proposal with necessary scrutiny and expertise. These committees provide a place for members to interact with subject experts and government officials while they are studying a bill (Kanwar, 2019).

60 per cent of proposals were referred to Standing or Select Committees during the United Progressive Alliance’s first term. During the UPA-II administration, this rose to 71 per cent. Modi’s first term from 2014-19 had a 27 per cent reference rate, while his second term so far has only a 12 per cent rate (Gowda M. R., 2021). Not only is there a blatant and marked disregard for referring bills to parliamentary committees, but the administration has also actively worked to hinder committee work. A meeting of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Information Technology on July 28, 2021, had to be cancelled owing to a lack of quorum when 15 BJP members refused to sign the attendance register. It is speculated this was to avoid the discussion on the Pegasus scandal.

Monsoon Session of Parliament 2021 and other Statistics

Adherence to the parliamentary procedure can be gauged through a wide avenue of categories including but not limited to hours lost to disruptions, adjournments, the productivity of each session, time spent on deliberation and so on.

A record number of 12 bills were passed by the parliament in the first 10 days of the monsoon session. All these bills were passed by a voice vote which is widely viewed as a largely inaccurate mechanism to assess supporters of a particular proposal. None of these 12 bills nor the overall 14 bills was referred to standing committees for in-depth analysis. According to TMC leader (Brien, 2021), Derek O’Brien in the monsoon session bills were rushed through and 12 bills were passed at an average time of under 7 minutes per bill (Brien, Indian Express, 2021). In the same vein, BSP MP Danish Ali commented that the Essential Defence Services Bill was passed in less than 10 minutes (Nair, 2021).

Since 2014, the 2021 monsoon session of the parliament ranks the third highest in terms of time lost to forced adjournments and interruptions. In this session, the number of sitting hours was, unfortunately, lower than the number of hours lost to disruptions which came to be around 74.46 hours.

The lack of debates on bills has become a major controversy. With a per bill time of fewer than 10 minutes, 14 new bills were passed in the monsoon session, a worrying number that indicates no involvement of the parliamentary committees, and no sustained debates, a feature essential to provide checks to freehand power (Radhakrishnan, 2021).

The time accorded to bill discussion is another avenue to assess the functioning of parliamentary procedure. In 2019, the average time spent on bill discussion stood at 213 minutes. At present, it stands at 85 minutes. Furthermore, in the 16thand 17th Lok Sabha, which subsumes the two terms of the Bhartiya Janata Party, 27% and 12% bills respectively were referred to parliamentary committees. In contrast during the 14th Lok Sabha (17 May 2004 – 18 May 2009) 60% of the bills were referred to parliamentary committees, and 71% of the bills were referred to the parliamentary committees for discussion in the 15th Lok Sabha (2009-14).

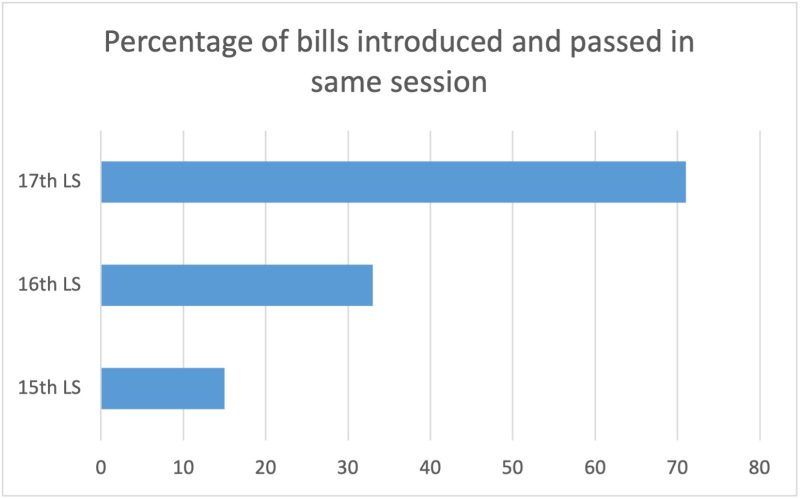

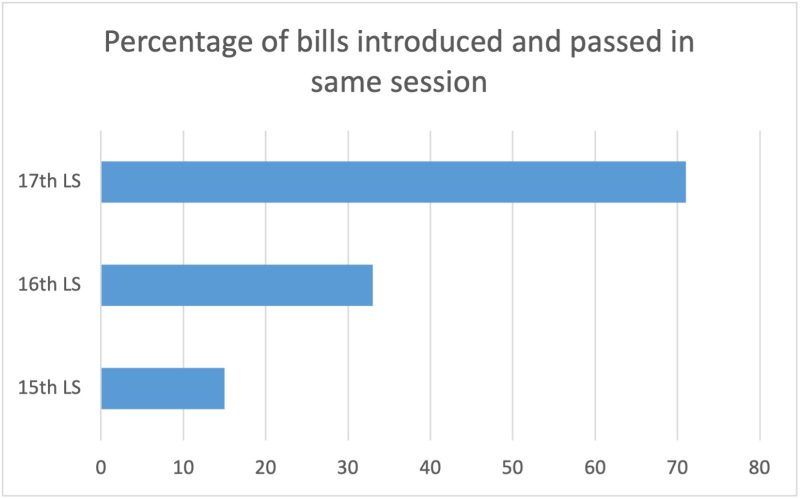

With regards to the passing of bills, around 18% of the bills were introduced and passed in the same session in the 15thLok Sabha. In the 16th Lok Sabha (2014-2019) this number jumped to 33 per cent while in the 17th one it increased drastically to 70%, indicating the lack of debate.

Conclusion

This paper has attempted to evaluate primarily the basic question of whether constitutional methods have been followed in policymaking under the Bhartiya Janata Party’s tenure. In doing so it has analysed the educational realm beginning from the recent criticisms against the NEP. These critiques highlighted that a centralised decision-making structure that is detrimental to federal values is visible alongside a lack of focus on secular education. Additionally, statements from top officials, policies of CBSE, and those responsible for the change in curriculum hint that policies of late seem to have an aim of fostering educational sensibilities that further an ideological agenda of the ruling party. The paper also attempted to broaden its lens to assess the larger process of policymaking and legislation. Herein it was determined that there is an incongruity between the parliamentary procedures of recent years and the constitutional norms. This includes the statistics that highlight a growing recourse to ordinances, the curtailing of question hour, minimal involvement of parliamentary committees and the excessive use of voice vote. The state of affairs in India at the moment stands to suggest that parliamentary procedures do not adhere to constitutional norms, and thus there is a reason for apprehension as this trend could give way to majoritarian politics and set precedent for unethical conduct in the political realm at large.

Works Cited:

Biswas, S. (2021, March 16). Electoral autocracy’: The downgrading of India’s democracy. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-56393944

Brien, D. O. (2020, September 11). The ordinance raj of the Bharatiya Janata Party. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://www.hindustantimes.com/analysis/the-ordinance-raj-of-the-bharatiya-janata-party/story-NlVvn0pm6updxwYlj0gSvJ.html

Brien, D. O. (2021, August 7). Autocratic Government doesn’t want Parliament to Function. (NDTV, Interviewer)

Brien, D. O. (2021, August 5). Indian Express. Retrieved October 31, 2021, from https://indianexpress.com/article/india/parliament-monsoon-session-bills-passed-derek-obrien-7440026/

Dam, S. (2015, June 3). Repromulgation Game. Retrieved October 30, 2021, from https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/columns/legal-eye-column-repromulgation/article7275518.ece

Gowda, C. (2019, June 26). Missing secularism in National Education Policy. Retrieved November 7, 2021, from https://www.livemint.com/education/news/missing-secularism-in-new-education-policy-1561564775831.html

Gowda, M. R. (2021, August 16). The 2021 Monsoon Session Is Proof of Modi Govt’s Disregard for Parliament. Retrieved October 31, 2021, from https://thewire.in/government/the-2021-monsoon-session-is-proof-of-the-modi-govts-disregard-for-parliament

Guha, R. (2019, April 28). Modi Government’s surgical strike against science and scholarship. Retrieved November 10, 2021, from https://thewire.in/education/the-modi-governments-surgical-strike-against-science-and-scholarship

Jaffrelot, C. G. (2019). BJP in Power: Indian Democracy and Religious Nationalism. Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Jha, J. a. (2019, September 10). India’s education budget cannot fund proposed education policy. Retrieved November 1, 2021, from https://www.indiaspend.com/indias-education-budget-cannot-fund-proposed-new-education-policy/

Kanwar, S. (2019, September 19). Importance of Parliamentary committees. Retrieved November 1, 2021, from https://prsindia.org/theprsblog/importance-parliamentary-committees

Koshy, J. (2018, March 16). Stephen Hawking said Vedas had a ‘theory’ superior to Einstein’s thesis, says Harsh Vardan. Retrieved November 10, 2021, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/stephen-hawking-said-vedic-theory-superior-to-einsteins-science-minister-claims/article23272193.ece

Lok Sabha Secretariate, N. D. (2014, May). How a bill becomes an act. Retrieved October 28, 2021, from Parliament of India – Lok Sabha: http://164.100.47.194/our%20parliament/How%20a%20bill%20become%20an%20act.pdf

Madhvan, M. (2021). Ordinance route is bad repromulgation is worse. PRS Legislative research. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from https://prsindia.org/articles-by-prs-team/the-ordinance-route-is-bad-repromulgation-worse

Madhvan, M. (2021, April 19). The Ordinance route is bad, repromulgation is worse. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from https://prsindia.org/articles-by-prs-team/the-ordinance-route-is-bad-repromulgation-worse

Menon, S. (2020, August 11). Imposing NEP on the states. Retrieved October 30, 2021, from https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/comment/imposing-nep-on-states-124964

Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. (2020). National Education Policy 2020. New Delhi: MHRD, Government of India.

Nair, S. K. (2021, August 3). The Hindu. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/opposition-cries-foul-as-12-bills-were-passed-in-10-days-of-monsoon-session/article35707105.ece

Prakash, G. (2019). Emergency Chronicles. Princeton University Press.

Radhakrishnan, V. S. (2021, August 17). 2021 Monsoon session: LS passed 14 Bills after discussing each less than 10 minutes. Retrieved October 30, 2021, from The Hindu: https://www.thehindu.com/data/data-2021-monsoon-session-ls-passed-14-bills-after-discussing-each-less-than-10-minutes/article35955980.ece

Rahman, M. (2014, October 28). Indian prime minister claims genetic science existed in ancient times. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/28/indian-prime-minister-genetic-science-existed-ancient-times

Raveendhren, R. S. (2020, August 19). New education policy and erosion of state powers. Retrieved November 1, 2021, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/new-education-policy-and-erosion-of-states-powers/articleshow/77624663.cms

Sanghera, T. (2020, August 6). Modi’s textbook manipulations. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/08/06/textbooks-modi-remove-chapters-democracy-secularism-citizenship/

Sharma, N. (2020, August 18). New Education Policy an attempt to centralise education: Opposition-ruled states. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/new-education-policy-an-attempt-to-centralise-education-opposition-ruled-states/articleshow/77604704.cms