Book Name: The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths

Author: Mariana Mazzucato

Publisher: Anthem Press (10 June 2013)

Page Count: 266

Price: INR 2,020.00

Written against the backdrop of the recovery period of the financial crisis of 2008, Mariano Mazzucato’s ‘The Entrepreneurial State’, came at a critical point, arguing against the widely accepted belief of the self-correcting nature of the markets, and the austere state measures of limited intervention, which in the case of the financial crisis, referred to injecting large sums of capital in banks to rescue them from collapsing. The book is an expanded version of a 2011 report which laid down policy proposals for the UK government post the crisis.

Divided into ten chapters, the book focuses on the need for the institutionalization of innovation and lays down two main arguments. First, state investment is a necessary pre-condition for any long-term innovation, and growth, and requires a steady flow of funds. Arguing that governments must move beyond spending solely on infrastructural development, Professor Mazzucato extensively explains how the state and the industry are interwoven together, and cannot be looked at, in isolation. She draws her examples from a wide spectrum of industries in the United States, covering the pharmaceutical companies, to big tech companies, while also linking the state and industry to public schools, and foreign and defence policies of the United States.

Second, the book argues that the companies funded by the state should return a part of their profit to the state for investment in other innovative technologies. Here, it is important to note that while the book has been targeted by neo-liberals for suggesting socialization through increased state intervention in the market, the author, however, does not question the right of private companies to accumulate profits, and asks only a proportion of it to be redistributed to the state for further investment.

A major part of the book is devoted to addressing the illusion that entrepreneurship and innovation come from the private sector alone. Debunking this myth, Professor Mazzucato cites extensive evidence of impatient venture capitalists who have historically depended upon the government support for expensive and ambiguous investment risk, and of companies that have historically preferred to repurchase their shares to increase their stock prices instead of investing in research. She highlights the role of the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) in the US which was set up to provide the country with technological superiority. Arguing that the agency played a critical role in funding computer and internet technology, she illustrates how its contribution to the success of companies in the Silicon Valley, is often overlooked by institutions seeking to get away from the long arm of the state’.

The author draws inspiration from Keynes’ advocacy of increased government expenditures, and Karl Polanyi’s research on central organization and state’s policies of controlled interventionism, where he argued that it was the state-imposed conditions that made a conducive environment for markets to come into existence. She also draws some of her important arguments from Schumpeter’s idea of entrepreneurial innovation and experimentation which paves the way for innovation by constantly destroying the old ones. Throughout her book, Mazzucato argues for a symbiosis of Keynesian fiscal spending, and Schumpeter’s investments in innovation.

The book challenges the widely promoted concept of a free market based on limited state intervention, by the United States. Claiming that the US has itself invested heavily into its research and industrial sector, the author looks into the role played by programs and agencies like DARPA, Small Business Innovation Research (required large companies to designate a proportion of their funding to small for-profit firms), the Orphan Drug Act (provides tax incentives, subsidies, and intellectual and marketing rights to small firms dedicated to developing products for the treatment of rare diseases) and the National Nanotechnology Initiative. Further, after comparing the data of several countries, the author argues that states like Portugal and Italy are lagging not because of high state presence, but rather due to lack of state investment in research and development.

The author builds up her argument upon the foundation that the state lacks confidence in its abilities to fund innovation. She argues that an increasing number of research and financial institutions have wrongfully come to regard the state as the ‘enemy of the enterprise’, which should be kept away from meddling in the market to ensure efficiency. Although she does briefly mention that the citizens are often unaware of how their taxes foster innovation, her analysis does not delve into the reason behind the state’s lack of confidence in itself, making it difficult for the reader to grasp the reason behind the state’s as well as the society’s lack of trust in a public-funded healthcare system, despite most new radical drugs have been coming out of public labs.

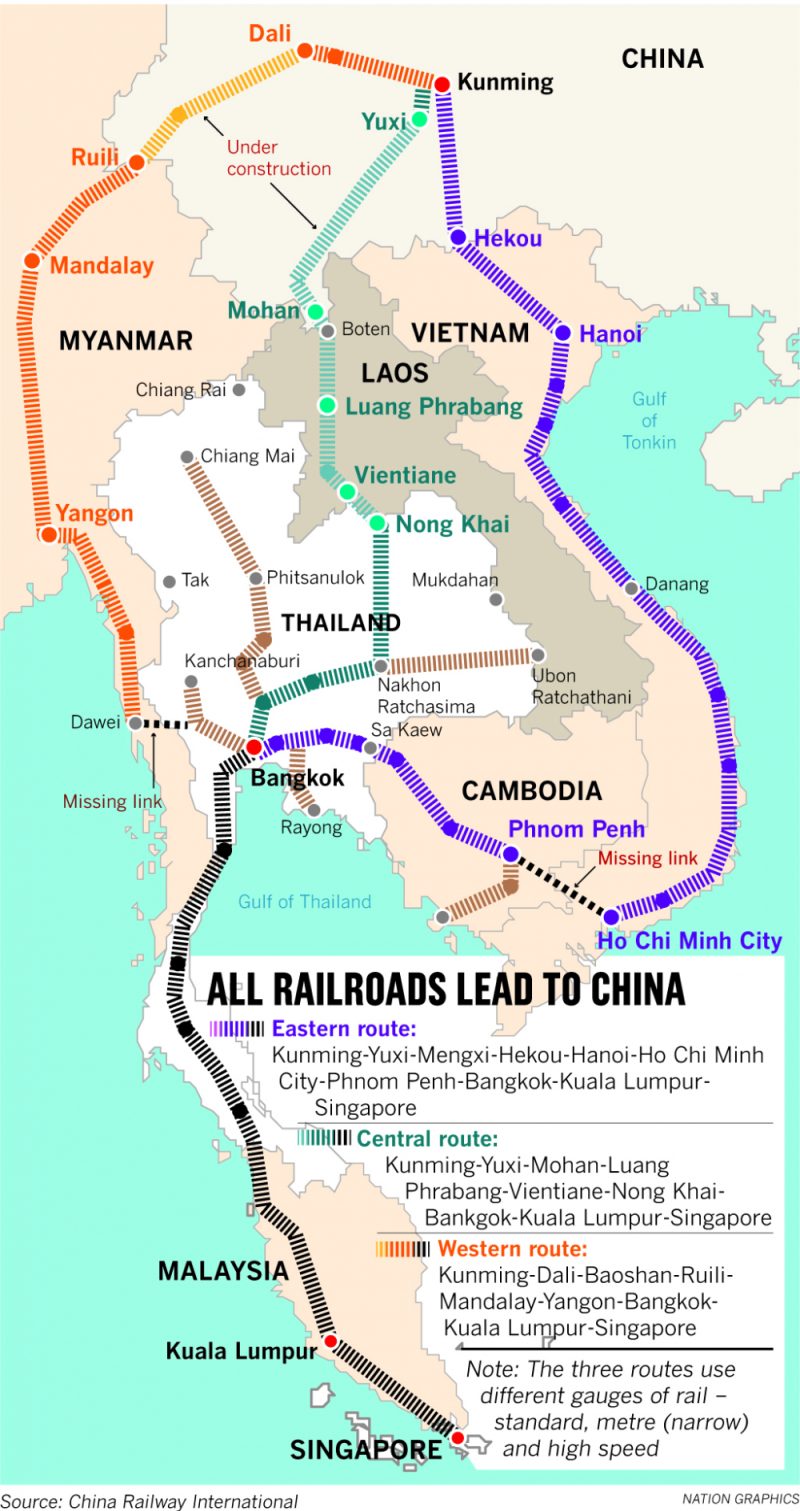

Writing on the importance of green technology, Mazzucato holds that any ‘green revolution’ would depend upon an active risk-taking state. While comparing the green economic policies of China, Brazil, the US, and Europe, she elucidates how the state investment banks in China and Brazil act as a major source of funding for clean and solar technology. On the other hand, Europe’s approach to clean technology funding has been weakened by its attempt to present ‘green’ investments as a trade-off for growth, consequently resulting in a lack of support.

Towards the latter part of her book, Professor Mazzucato presents her hypothesis of the risk-taking state, where both the state, and the market are interwoven to generate growth, and innovation. Her proposal is supported by numerous examples of state-sponsored innovative technology which emerged in the last century, implying that the state may have always been entrepreneurial. However, she argues that countries like India have performed worse than others because of their over-expenditure on several small firms, which have low productivity and output. The focus of state investment, thus, should be placed not on its quantity, but rather on its distribution amongst different sectors of the economy.

Mazzucato claims that since the traditional tax system cannot provide the state with funds to invest in the innovation system because of tax avoidance and evasion, she suggests a three-step framework to support state-funded innovation. First, the state should extract royalties from the application of a technology that was funded by the state itself, which should be put into a ‘national innovation fund’ for future investment. Second, the state should put conditions on the loans it offers, a part of which should be returned to the state when the company starts to earn profits. And finally, she argues for the establishment of a State Investment Bank, like those in China and Brazil.

The relevance of her hypothesis increases significantly as one witness the market value of Apple moving past the mark of $3 trillion, and surpassing the GDP of countries like the UK, Italy, Brazil, and Russia.[i] The author debunks the overestimated role of the big private companies like Apple and Google being at the forefront of generating innovative technologies by themselves alone. In doing so, she argues that Apple has received state funds from various channels, including direct investments in their early stage of development under the government programs like the Small Business Innovation Research; through access to technologies that emerged primarily because of state funding; and through the tax policies which benefit the company. Most of the elements used by the Apple, including high-speed internet, SIRI, touch-screen displays have been a result of risky investments by the state.

Scholars[ii] have argued that the book does not consider the ‘productivity paradox’, which reflects low productivity in times of emerging innovative technologies, as during the IT revolution of the 1970s in the United States. However, it is important to note, that Mazzucato argues against the endogenous growth theory, where the output is taken as a function of capital, and labour, with technology assumed as an exogenous variable. She targets the theory for assuming certainty in growth after investment in technology, and research and development. Taking inspiration from Schumpeter, she asserts that investment in technology and innovation involves high uncertainty, and the growth, thus, cannot be measured using a linear model like the endogenous theory, which does not take into account the social factors responsible for growth (education, design, training, etc.).

One of the limitations of the book is its lack of analysis on the underlying structural inequality and the impact of technological change on income disparities. Instead of delving further into controversies of value creation, the author cites an example of the wage-disparity between Apple’s broader employee base and its top executives and observes that the process of innovation can go ahead simultaneously with inequality. In the case of Apple, the products of which are considered as global commodities, a major part of the workforce come from countries providing cheap labour. These offshore jobs mostly take place in the low-wage manufacturing industries, and the resulting profit margins are counted as ‘value added’ generated within the United States[iii]. While Mazzucato argues for redistribution of profit between Apple and the US government, her analysis ignores the role played by the globalized workforce in generating the said profits.

Lastly, the case for a risk-taking entrepreneurial state has been made solely based on politically stable, high-income countries of the West. The author does not address whether high-scale state investments would be viable in situations where governments’ primary focus is placed on maintaining domestic stability and security, as in the case of Afghanistan, Somalia, or Yemen. Thus, one cannot be fully convinced about whether the prescribed model would fit well into the low-income countries of the South, many of which continue to witness high levels of instability, corruption, and violence.

Overall, in using over three hundred different sources, Professor Mazzucato’s book provides the reader with an extensive critical insight into the working of the state, and the industry. By addressing the various myths associated with industries in each of her chapters, the author makes the reader question the fundamentals of the free-market system and makes one interrogate the existence of such a system. The book also attempts at breaking the cultural hegemony of the United States, by challenging their mainstream narrative of high-scale privatization and limited government presence. By covering a vast ground of industries, the book pushes the reader to delve into further research to investigate the role of the state in funding other technologies and innovations.

[i] Bursztynsky, J. (2020, August 19). Apple becomesfirst U.S. company to reach a $2 trillion market cap. Retrieved August 20, 2020, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/08/19/apple-reaches-2-trillion-market-cap.html and Smith, Zachary Snowdon. (2022, Jan 03). Apple becomes 1st company worth $ 3 trillion – Greater than the GDP OF UK. Retrieved March 08, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/zacharysmith/2022/01/03/apple-becomes-1st-company-worth-3-trillion-greater-than-the-gdp-of-the-uk/?sh=6142c7b25603

[ii] Pradella, L. (2016). The Entrepreneurial State by Mariana Mazzucato: A critical engagement. Competition & Change, 21(1), 61-69. doi:10.1177/1024529416678084

[iii] Greg Linden, Jason Dedrick, and Kenneth L. Kraemer, Innovation and Job Creation in a Global Economy: The Case of Apple’s iPod, Personal Computing Industry Center, UC Irvine, January 2009, http://pcic.merage.uci.edu, 2.

Feature Image Credit: Mariana Mazzucato Quartz