The Houthis started in the 1990s as an armed group in Yemen, fighting against corruption. They belong to a community called Zaidis, who are a part of the Shia-Muslim minority. Along with Hamas and Hezbollah, the Houthis have declared themselves to be a part of the Iranian-led “axis of resistance” against Israel, the US, and the larger West.1 The Houthis have been attacking commercial ships passing through the lower Red Sea, and this has dramatically increased since mid-November in retaliation to Israel’s bombardment of Gaza. Due to these events, the Red Sea trade route is significantly affected, impacting the flow of global trade and having the potential to cause further damage. With ships attacked and stranded in one of the leading shipping routes of the world, countries seem to find themselves in yet another geopolitical fix. As the war continues between Israel and Gaza, the Red Sea has become a renewed hotspot for geopolitical and military tensions.

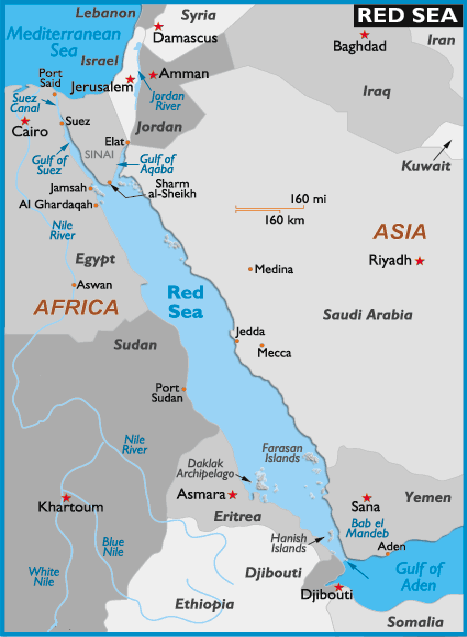

Situated between Africa and West Asia, the Red Sea is a seawater entrance to the Indian Ocean in the south and goes through the Gulf of Aden and the Bab El Mandeb Strait, meeting the Gulf of Suez in the north. Countries like the US, France, Japan, and China have military bases in the region, including in Djibouti and many along the Horn of Africa, with considerable deployment of ships, weapons, and personnel. Establishing such bases conveys how critical it is to have control of the area as a measure of regional power and as a way of asserting their dominance internationally. Big players, including the Cold War rivals, have long struggled to gain presence and influence in West Asia. Having a military and economic presence in Africa with proximity to the Red Sea was necessary, for it provides access to almost 12% of the world’s trade, including nearly 40% of the trade between Europe and Asia.2

Until recently, the Houthis had been targeting ships heading towards Israel or ones that Israelis owned. However, recent developments showing attacks on ships bound for Israel with flags of various countries have raised grave concerns for global trade and security in the immediate future. The US, along with countries like the UK, France, and Bahrain, have tried to stop Houthi attacks on ships passing through the Red Sea under what Washington calls the “Operation Prosperity Guardian”. On the first day of the new year, The US military released a statement conveying that they killed at least 10 Houthi rebels and sabotaged three Houthi ships. Although the US was successful in deterring the Houthis from their attempt to attack, it did not do much to stop the group from being involved in disrupting peaceful navigation through the Red Sea.

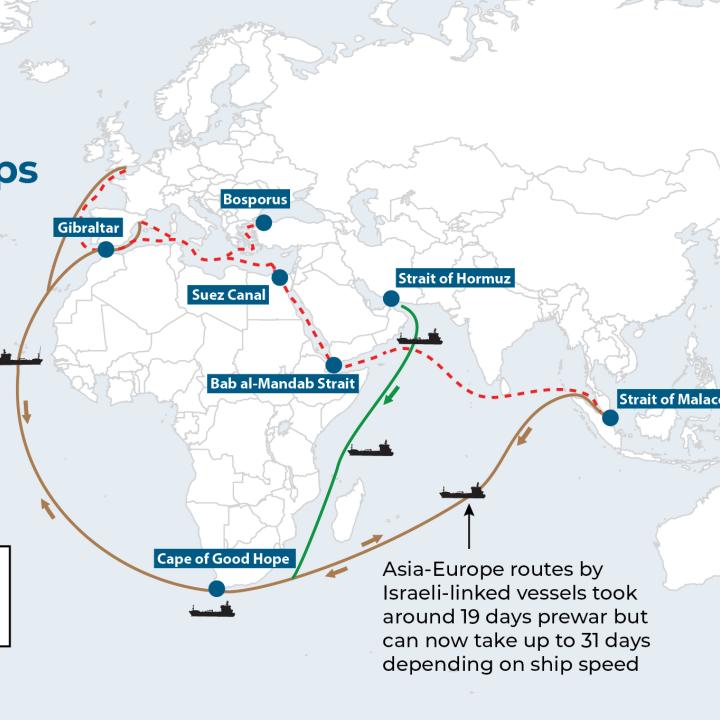

Private shipping companies such as Maersk, CMA CGM, Hapag-Lloyd, and MSC have begun to avoid using the Red Sea route due to the imminent threat from Houthis.3 The ongoing supply chain disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could further escalate due to the Red Sea crisis and cause severe concerns for world trade and consumer goods supply. With the suspension of trade via the Suez Canal, traffic through the Red Sea has dropped by 35%.4 The Houthis have raised the shipping cost internationally, imposing additional costs on commerce when trouble at the Panama Canal due to low water levels has already made shipping more complicated and central banks worry about a new inflationary spike. While trade hasn’t wholly stopped, most ships can choose the longer but safer route around Africa through the Cape of Good Hope to reach Europe and Asia from either side. This option imposes significant costs on shipping and, therefore, to consumers and affects local states in the region if the Houthi “blockade” persists. In the worst-case scenario, crude oil prices would rise in 2024 if oil shipments through the canal were stopped entirely, and this could cause a significant disturbance.

Image Credit: washingtoninstitute.org

Surprisingly, though, Russian ships have enjoyed free navigation through the Red Sea. Russian ships travel to Asia through the Black Sea, connecting to the Mediterranean Sea, passing through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea, and joining the Indian Ocean. With sanctions from Europe and the US amid the war in Ukraine, Russia cannot afford to lose its markets in Asia, particularly India and China, since these two countries buy almost 90% of Russia’s oil exports.5 The free navigation of Russian ships could possibly be due to its close relationship with Iran or due to the adoption of a similar stance with the Houthis on the war between Israel and Gaza. In the unlikely scenario that Russia does not have access to the Red Sea, it leaves them with the only other option of travelling through the Cape of Good Hope, adding 8,900 kilometres with an additional two weeks of travel. Such delays in oil shipments and a highly possible hike in price may prompt countries like India and China to start looking for other alternatives to their oil requirement, given the pre-existing energy crisis. Most probable alternatives include Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries that do not need to pass the Red Sea to reach the Indian Ocean and thus Asian markets since they have ports in the Persian Gulf with access to the Arabian Sea.

The disruption in trade has caused an impact on Indian imports and exports as well. Indian exports traverse the Indian Ocean and reach the Suez Canal through the Arabian Sea to reach European markets. Trade between India and Europe has been rising, at an all-time high in 2022, with goods traded worth $130 Billion.6 As of 2021, India engaged in trade worth $200 Billion through the Suez Canal, making the EU one of India’s main export destinations, with a Free trade agreement in the talks.7 India also procures its oil from Russia using the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. A slowdown or possible pause of oil imports may cause severe concerns amid the ongoing energy crisis. At such a juncture for the Indian economy, if the situation persists, trade will likely take a hit along with India’s domestic economy. If the condition fails to change decisively, the higher fees and the expense of prolonged travel duration will also put inflationary pressure on the global economy and India.

The Houthis will most likely continue to put pressure on Israel to stop its onslaught in Gaza, and they are likely to keep attacking until they reach their goal. By taking control of the Red Sea and indirectly and directly hurting countries irrespective of their size and power, Houthis pressurize the international community to, in turn, put pressure on Israel. This also means that the group is unlikely to agree on any other way of settlement. Not only does this fall on Israel to stop their attacks but also on the US since the latter has always portrayed itself as a peace negotiator in the Middle East and, therefore, has the responsibility to restore order in the region. The Houthis possess a plethora of Iranian-supplied weaponry, ranging from precision drones to anti-ship cruise and ballistic missiles that can strike a moving vessel hundreds of kilometres away. What makes the Houthis more dangerous is the enormous stockpile that can help them continue their campaign indefinitely.

The attacks have also prompted an unanticipated return of Somali piracy in international seas. As a result, increased expenses are now a worry for merchant shipping lines and seafarer safety for governments worldwide. The ship Lila Norfolk, under the Liberian flag and carrying six Filipinos and fifteen Indians, was taken over by Somali pirates on January 4th, 2024. The Indian navy had already deployed four warships patrolling the Indian Ocean, including INS Chennai, which was involved in the rescue operation during the recent highjack of ship Lila Norfolk. Even though the Indian Navy’s intervention allowed for the sailors’ rescue, it caused further concerns for India’s security and economy. The spill over of these attacks onto the Indian Ocean may threaten India’s security.

Countries must monitor developments in the Red Sea and, for India, the Indian Ocean. Although India has not joined any Western-led operations on this matter, the country must push the international community to ensure freedom of navigation and the territorial integrity of countries over their sea is upheld under the UN Convention on the Law of the Seas.

References

[1] Who are the Houthi rebels and why are they attacking Red Sea ships? (2023, December 23). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-67614911

[2] Yerushalmy, J. (2023, December 19). Red Sea crisis explained: what is happening and what does it mean for global trade? The Guardian.

[3] A new Suez crisis threatens the world economy. (2023, December 16). The Economist. https://www.economist.com/international/2023/12/16/a-new-suez-crisis-threatens-the-world-economy

[4] Graham, R., Murray, B., & Longley, A. (2023, December 19). Houthi Red Sea Attacks Start Shutting Down Merchant Shipping. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-12-18/houthi-attacks-start-shutting-down-red-sea-merchant-shipping

[5] Russia: crude oil shipments by destination 2023 | Statista. (2023, September 14). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1350506/russia-crude-oil-shipments-by-destination/

[6] I. (n.d.). First India-EU Trade and Technology Council: Significant Milestone in India-EU Relations – Indian Council of World Affairs (Government of India). https://www.icwa.in/show_content.php?lang=1&level=3&ls_id=9416&lid=6112#:~:text=The%20EU%20is%20India’s%202nd,EU%20total%20trade%20in%20goods.

[7] Ibid.

Feature Image Credit: dailynewsegypt.com

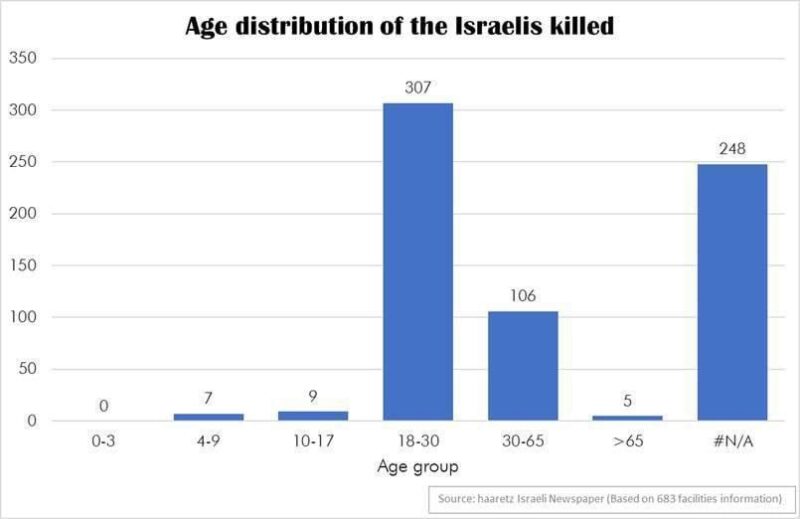

Age Distribution of the Israelis killed during Hamas’ October 7 operation (as of 23 October)

Age Distribution of the Israelis killed during Hamas’ October 7 operation (as of 23 October) Aftermath or Be’eri Kibbutz after the fire power of the two sides cease

Aftermath or Be’eri Kibbutz after the fire power of the two sides cease