Summary

Sri Lanka sits at a strategic crossroads, with geography that positions it at the heart of global trade and regional security. Yet economic vulnerability, political inconsistency, and limited strategic clarity have constrained its influence. As global power fragments and the Global South rises, the island faces a choice: remain reactive and peripheral or leverage its location, strengthen its economy, and build stable institutions to become a neutral logistics hub, a trusted diplomatic partner, and an active contributor to the emerging multipolar order. Acting decisively now will transform strategic opportunity into lasting national influence.

Over the past four years, geopolitical, economic, and technological shifts have progressed at a pace unmatched in the previous three decades. The world we face today is fundamentally different from the one we knew before. War has returned to Europe, shattering the assumption that major interstate conflict on the continent was a thing of the past. The Middle East is once again engulfed in overlapping crises that draw in both regional actors and global powers. Across Africa—from the Sahel to the Horn—coups, insurgencies, and persistent violence are eroding state institutions and deepening humanitarian emergencies. The impact of Trump’s tariffs threatened many sectors globally.

At the same time, trust in multilateral institutions, long the guardians of global order, is fading. The UN struggles to act decisively, the WTO is weakened, and even climate negotiations are increasingly shaped by national interests rather than collective responsibility. The consensus that once underpinned global cooperation is fragmenting.

Meanwhile, technological disruption is accelerating competition. Artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and strategic supply chains have become the new battlegrounds for influence. Nations no longer compete only for territory or ideology; they compete for data, minerals, energy, and technological dominance.

The post–Cold War optimism that once promised a borderless world of global democracy and free markets has evaporated. In its place has emerged an era defined by political fragmentation, economic rivalry, and strategic competition. Great-power tensions are rising, regional blocs are hardening, and smaller states are being compelled to navigate an increasingly complex and divided international landscape.

The rules-based order that emerged after World War II is weakening, and neither the United States nor China can dictate the future alone. Instead, a triangular contest among the global West, global East, and the global South is shaping a new geopolitical reality.

In addition, the Indo-Pacific has become the central arena of strategic competition between the United States and China. As China expands its economic reach, military power, and political influence, the U.S. seeks to uphold a free, open, and rules-based regional order. This rivalry now shapes security, diplomacy, trade, and technology across the entire region, with flashpoints such as the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea posing the greatest risks of confrontation and global economic disruption.

Where does Sri Lanka stand

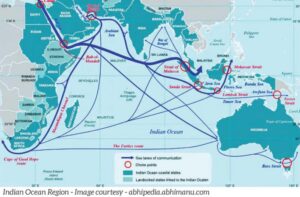

Sri Lanka is a small island nation, but one with a singular and powerful advantage: its geography. Positioned at the center of the world’s busiest East–West maritime corridor, the island lies along sea lanes that carry nearly two-thirds of global oil shipments and almost half of all container traffic. In an era when supply chains, shipping routes, and energy pathways are becoming strategic assets in their own right, Sri Lanka’s location is not merely convenient—it is consequential.

This makes the island strategically valuable to every major power. For India, Sri Lanka’s stability is essential to security in its immediate neighbourhood and to its ambitions in the wider Indian Ocean. For China, the island is a vital node in the Belt and Road Initiative, linking the maritime silk route to broader trade and energy networks. For the United States, Sri Lanka is central to its Indo-Pacific strategy, where freedom of navigation, open sea lanes, and counter-balancing rival influences are paramount.

Beyond the great powers, there is a range of middle powers, which includes Japan, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and even Turkey. These countries are deepening economic, maritime, and diplomatic engagement across the Indian Ocean. Their interests converge on Sri Lanka not merely because of geography, but because of the island’s potential as a stable partner, a logistical hub, and a platform for regional connectivity. Collectively, these factors position Sri Lanka as not just a nation-state but a geopolitical crossroads, where the interests of global and regional actors meet, overlap, and at times compete.

Yet, despite this inherent strategic value, Sri Lanka continues to struggle in transforming geography into meaningful geopolitical influence. The island’s location offers an extraordinary opportunity, but opportunity alone does not translate into power.

Policy inconsistency—driven by frequent political turnover, short-term decision-making, and competing domestic priorities—has created persistent uncertainty that discourages long-term investment and undermines Sri Lanka’s international credibility. At the same time, an overly cautious geopolitical posture, often bordering on indecision, has prevented the country from defining a clear strategic identity in the Indian Ocean.

As a result, Sri Lanka has too often been a reactor rather than an actor: responding to external pressures instead of anticipating them, accommodating the interests of major powers instead of assertively advancing its own. Although global actors are drawn to the island because of its strategic location, Sri Lanka has not consistently leveraged that interest to secure lasting economic, diplomatic, or security advantages.

The task ahead is to break this cycle. Sri Lanka must transition from being merely a geographical point of convergence to becoming a strategic participant capable of shaping outcomes that affect its future. This requires strengthening the domestic economic base, setting coherent long-term foreign policy priorities, and building the institutional stability needed to negotiate with confidence. Only then can Sri Lanka convert its location into lasting influence—anchoring its long-term security, enhancing its prosperity, and securing a respected place within a rapidly reordering world.

For countries like Sri Lanka, the challenge is to navigate this environment with careful diplomatic balance—leveraging economic opportunities from both the U.S. and China while preserving strategic autonomy and avoiding undue dependency. At the same time, Sri Lanka’s trade-driven economy relies heavily on stable, rules-based maritime routes across the Indian Ocean and the wider Indo-Pacific, making regional peace and open sea lanes essential for national economic stability.

The Weak Link in Sri Lanka’s Strategy.

The 2022 economic crisis significantly weakened Sri Lanka’s geopolitical standing. A nation’s foreign policy is only as strong as the economic foundation beneath it. When an economy collapses, sovereignty is not formally lost, but it is quietly constrained. Sri Lanka’s reliance on external lenders, bilateral creditors, and major-power investments has narrowed its strategic flexibility and limited its ability to negotiate from a position of strength.

Instead of shaping regional agendas, we increasingly find ourselves adjusting to those set by others. Unless Sri Lanka restores economic resilience and rebuilds fiscal credibility, the country risks becoming a pawn in a larger great power contest rather than a strategic actor capable of advancing its own interests.

Real impact on Sri Lanka

The Trump administration’s imposition of tariffs on Sri Lankan exports functioned as a form of trade restriction rather than a targeted sanction or financial embargo. Nevertheless, the measures had material implications for the country’s economy. The garment sector, which constitutes the backbone of Sri Lanka’s foreign-exchange earnings and employment, was particularly exposed. Given that the United States represents a significant share of Sri Lanka’s export market, the tariffs threatened to impede post-2022 economic recovery and constrain critical foreign-exchange inflows. Beyond immediate economic effects, the episode highlights Sri Lanka’s structural vulnerability to shifts in global trade policy, revealing a broader strategic challenge: without enhanced economic resilience and proactive engagement in international trade frameworks, Sri Lanka risks being perpetually reactive rather than an influential actor in the global economic system.

The Global South Is Rising

One of the most consequential geopolitical shifts of our time is the emergence of middle powers within the Global South as influential actors in global affairs. Countries such as India, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey, Nigeria, Indonesia, and Mexico are no longer peripheral participants in a system dominated by the West. They possess the economic weight, demographic scale, technological ambition, and diplomatic confidence to reshape global institutions, from trade and finance to climate governance and security frameworks.

This rise is visible everywhere. India is now the world’s fastest-growing major economy and a central player in the G20 and Indo-Pacific. Brazil shapes global environmental and agricultural policy. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are redefining energy geopolitics and investing heavily across Asia and Africa. South Africa and Nigeria influence continental politics, peacekeeping, and resource diplomacy. Turkey has become a pivotal actor in West Asia, Central Asia, and global mediation efforts. Together, these countries are forming new coalitions, from BRICS+ to the G20’s expanded role, challenging the old North–South divide and demanding a more equitable international order.

And yet, amid this global transformation, Sri Lanka remains largely absent from the strategic conversation. We participate in international forums, but seldom shape their agendas. We attend summits, but rarely articulate a coherent long-term national strategy. The country possesses clear potential, but lacks the strategic clarity and diplomatic consistency required to convert that potential into influence.

Sri Lanka belongs to the Global South by geography, history, and shared developmental challenges—but not yet by strategic weight or leadership. At a time when emerging powers across Asia, Africa, and Latin America are redefining global governance, Sri Lanka risks remaining on the sidelines. Unless we strengthen our capacity to articulate priorities, build alliances, and engage proactively, we may become spectators in a moment when others are reshaping the international order.

If the Global South continues its ascent as current economic, demographic, and diplomatic trends indicate, it will become a decisive force in global negotiations on climate, trade, energy, technology, and security. The question then becomes: Where will Sri Lanka stand? We must choose whether to meaningfully align with this emerging bloc, articulate our own national priorities, and build partnerships that reflect our strengths or risk being left behind, irrelevant in a world that is rapidly reorganising itself.

Opportunities in the New Disorder

Disorder brings danger, but it also brings opportunity. History shows that moments of global turbulence create openings for small, agile states to elevate their influence. Finland, Singapore, Qatar, and the UAE are prime examples—nations that turned geography, diplomacy, and strategic clarity into disproportionate global relevance. They became connectors, mediators, hubs, and conveners at a time when great powers were distracted by rivalry. Sri Lanka, too, possesses the attributes to rise in this emerging landscape, if we choose to act with purpose.

As a Maritime and Logistics Hub, Sri Lanka sits along the world’s most important East–West maritime highway, yet has not fully realised the potential of this position. With the right investment climate, regulatory consistency, and diplomatic balance, the island can become an efficient, neutral logistics hub serving all blocs: West, East, and South. This includes strengthening ports, aviation links, and digital infrastructure to support regional supply chains and trans-shipment networks.

As a Diplomatic Bridge in the Indian Ocean Geopolitics in the Indo-Pacific is increasingly defined by competition, mistrust, and strategic ambiguity. Amid this environment, Sri Lanka can offer what few others can: a neutral, trusted venue for dialogue, confidence-building, and conflict prevention. By convening maritime security forums, climate adaptation roundtables, and regional economic dialogues, Sri Lanka can redefine itself as a facilitator rather than a battleground for competing interests. This diplomatic role, rooted in neutrality and credibility, can become a cornerstone of the island’s long-term relevance.

The global transition to clean energy is rewriting economic and political priorities across continents. Sri Lanka’s hydropower, solar, and wind capacity create an opportunity to position the country as a renewable energy partner for the region. Expanding grid connectivity, attracting green financing, and partnering on technology transfers can anchor national energy security while forging deeper alliances with both great powers and rising middle powers as a Renewable Energy Partner.

As the Global South demands a fairer international order, Sri Lanka has the opportunity to join voices calling to democratise global governance, from the UN Security Council to the IMF and World Bank. Smaller nations deserve equitable representation and greater institutional responsiveness. By aligning with reform-oriented coalitions, Sri Lanka can gain diplomatic visibility and credibility that far exceeds its size, as a Voice for Reform in Global Institutions.

But seizing these opportunities requires qualities we have not consistently demonstrated: political stability, coherent foreign policy, and economic credibility. These are the foundations upon which successful small states build influence, and they are the areas where Sri Lanka has repeatedly stumbled. If Sri Lanka can correct this trajectory, through disciplined governance, strategic clarity, and long-term national planning, then the disorder of today’s world need not be a threat. Instead, it can become the opening through which the island finally realises its potential as a regional connector, a diplomatic actor, and a resilient nation in a rapidly changing global order.

The Path Forward

Choosing Influence Over Vulnerability Sri Lanka must urgently embrace a new strategic mindset built on five pillars: Balanced Foreign Policy, Avoiding entanglement in rival blocs. Economic Transformation, Strengthening the economy to regain autonomous decision-making. Indian Ocean Strategy, Leveraging geography as a national asset, not a bargaining chip. Institutional Reform, building trustworthy governance that inspires investor and diplomatic confidence. Most importantly engagement with the Global South, positioning Sri Lanka as an active contributor to the emerging world order. The next decade will determine the shape of global power for a generation. If Sri Lanka hesitates, the world will move forward without us.

A Moment of Choice

Sri Lanka stands at a historic juncture. We possess strategic advantages that many nations envy, yet economic vulnerabilities limit our choices. The world is being reordered, messily, rapidly, irreversibly. The question is not simply Where does Sri Lanka stand today? The real question is: Where will Sri Lanka choose to stand tomorrow? In a world drifting toward rivalry and fragmentation, Sri Lanka must choose to be not a pawn, but a purposeful small power—neutral, stable, connected, and confident. This is our moment to reclaim agency. If we fail, the new world order will be written around us, not with us. The choice before us is stark, to remain a spectator in a world that is rapidly changing—or to step forward, with clarity and purpose, as a nation that shapes its own destiny.

References:

Alexander Stubb, The West’s Last Chance How to Build a New Global Order Before It’s Too Late January/February 2026 Published on December 2, 2025 https://www.foreignaffairs.com/

Rizwie, Rukshana; Athas, Iqbal; Hollingsworth, Julia “Rolling power cuts, violent protests, long lines for basics: Inside Sri Lanka’s unfolding economic crisis” (3 April 2022).

Wignaraja, Ganeshan (16 February 2025). “Sri Lanka struggles to deliver a new era of post-crisis growth | East Asia Forum”. East Asia Forum. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-17/shock-waves-from-the-war-in-ukraine-threaten-to-swamp-sri-lanka

https://www.reuters.com/markets/rates-bonds/sri-lankas-ambitious-governance-macro-linked-bonds-2024-12-17/#:~:text=LONDON%2C%20Dec%2017%20(Reuters),ever%20arranged%20in%20a%20restructuring.

https://www.voanews.com/a/india-feels-the-squeeze-in-indian-ocean-with-chinese-projects-in-neighborhood-/6230845.html

Reuters+2isas.nus.edu.sg+2

https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/tracking-impact-of-us-tariffs-on-apparel-footwear-supply-chains-wpftc/

Author:

Air Chief Marshal Gagan Bulathsinghala RWP RSP VSV USP MPhil MSc FIM ndc psc.

Formerly Commander Sri Lanka Air Force & Ambassador to Afghanistan

Director, Charisma Energy

Director, Strategic Development, WKV Group

President, Association of Retired Flag Rank Officers

Senior Fellow South Asia Foresight Network

Feature Image Credit: ndtv.com