China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), initially known as One Belt One Road (OBOR), was first announced in 2013 by President Xi Jinping. It aims to interconnect Asia, Europe, and Africa through two interlinked projects: the Belt as the land route, and the Road as the maritime route. The BRI aims to contribute significantly to overall economic or monetary development, as well as in the power generation area, it can further develop energy access and unwavering reliability in regions with quickly developing energy demand. Nonetheless, the BRI’s financial advantages and development of power frameworks might come at the cost of significant environmental degradation. The sheer size of the BRI has ignited increasing global concerns about the potential environmental damage. These concerns include ecologically sensitive areas, concern about the large amounts of raw materials needed, and locking in of various environmentally detrimental forms of infrastructure, for example, non-renewable energy (fossil fuel) related framework.

The BRI projects are instrumental in meeting the global CO2 emission targets; if all the BRI member states fail to reach the CO2 emission targets, that would result in a 2.7° C increase in the average global temperature.

There are numerous BRI projects which would pass through ecologically sensitive areas, thus compromising on such fragile regions. Some have even described BRI as the “riskiest environmental project in history”. The BRI has far-reaching influence, and it is estimated that the BRI investments are impacting over 60 per cent of the global population. The BRI projects are instrumental in meeting the global CO2 emission targets; if all the BRI member states fail to reach the CO2 emission targets, that would result in a 2.7° C increase in the average global temperature.

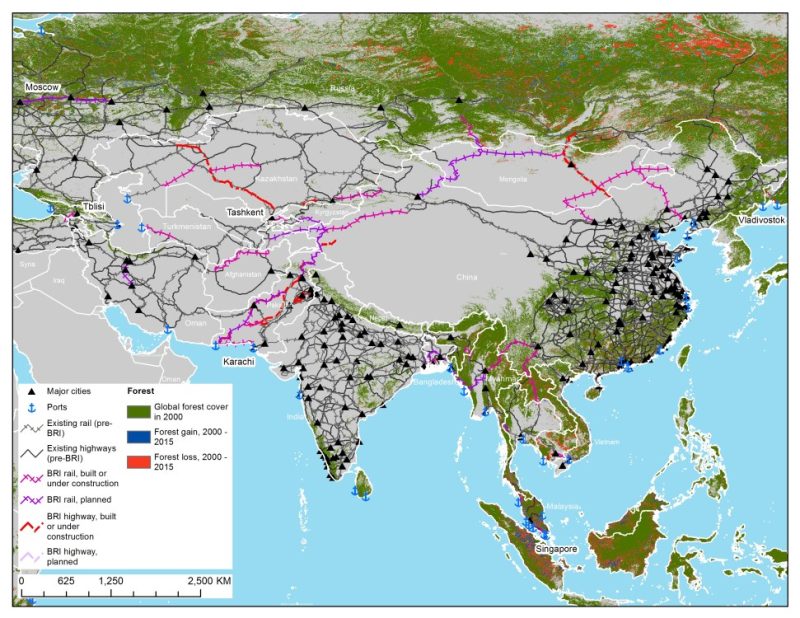

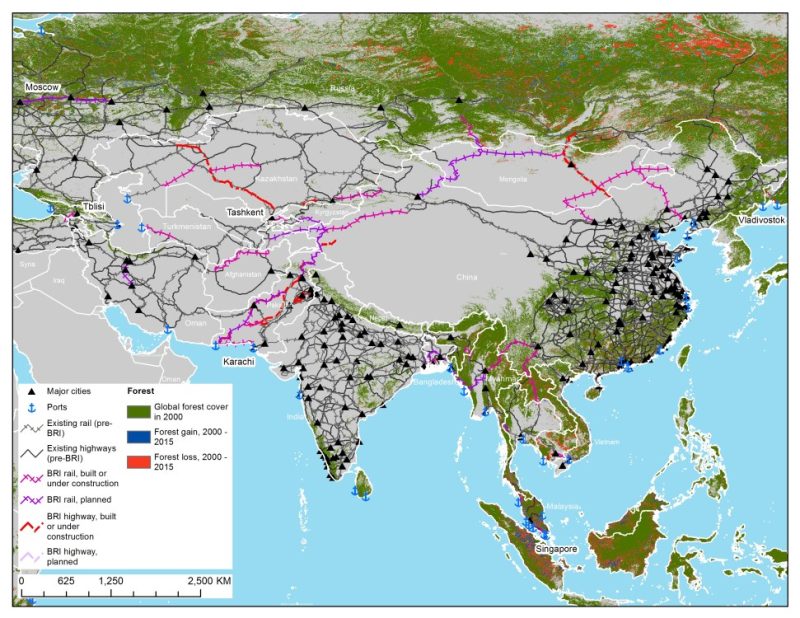

Securing and protecting the environment while encouraging financial advancement under the BRI will be extremely difficult and challenging, as the initiative crosses a different scope of fragile and delicate environments. Biophysical conditions range from woods and steppes in Russia; to ice, snow, and permafrost across the Tibetan Plateau; and tropical rainforests in Malaysia. Observers are worried about the natural threat that the BRI presents. Infrastructure advancement, trade, and investment ventures under the BRI could bring negative ecological impacts that might offset its economic gains. The possible effects of the BRI are complex and manifold. Foundation projects affect biological systems and wildlife, yet in addition aberrant impacts like logging, poaching, and settlement, adding to deforestation and other land related changes. The BRI could result in biodiversity loss because of fragmentation and debasement of various habitats, and cause increment in greenhouse gas emission due to the development and upkeep of transportation infrastructures and further Chinese interest in coal-terminated power plants. It could likewise speed up extraction of natural resources, like water, sand, and ferrous metal minerals and ores in nations along the BRI.

One such danger from BRI is the Russia–China Amur Bridge transport corridor, which takes apart two nature reserves with old growth forests. BRI framework will influence practically all of Eurasia’s biggest stream frameworks. Also, numerous BRI courses, for example the Karakoram Highway, go through geo-dynamically active regions. The Karakoram Highway linking the Xinjiang province in China to Gwadar Port in Pakistan, goes through Himalayan areas known for “extremely high geodynamic action” like seismic tremors, avalanches, frigid disintegration and erratic storms, but alternative pathways are even worse. In the Aral Sea, Central Asia, combined effects from the socio-ecological communications between misadministration, over-water system and serious contamination causing water shortage are amplified by truly dysfunctional transboundary management which can possibly result in armed conflicts. Heavily polluting Chinese concrete plants migrating to Tajikistan has been referred to as one illustration of this. Also, a logging ban in China’s Heilongjiang area caused spill-over impacts for forests overseas. Additionally, trade changes methods of production and utilization, changing income and along these lines contamination levels. As indicated by the Kuznets curve, pollution increments at first as income develops, yet over a defining moment, contamination falls as higher earnings bring innovative upgrades and expanding interest for ecological conveniences. Financial development might build the modern contamination base, known as scale effects. Negative scale effects and positive effects for the climate are hard to separate observationally, and quantitative examinations differ on whether the scale or procedure impact is bigger. Various toxins likewise respond diversely to exchange related changes. For instance, a Chinese report joining scale and method effects proposed that trade expanded SO2, and dust fall, however, decreased substance oxygen interest, arsenic and cadmium.

Arranging and resolving natural issues related with the BRI is colossally complex and multi-scaled. Understanding the attributes of the effects of BRI on the environment is the initial step for conceiving strategy and plans for addressing its effects on guaranteed sustainable development. The main mechanism to achieve the sustainability objectives of the BRI is cooperation, “characterized by governance guidance, business commitment, and social participation”. In any case, environmental governance accompanies different difficulties, first, BRI specific and related approaches are not unyielding, but rather dependent on intentional and corporate self-administrative instruments. China’s vision of a “green BRI” is probably not going to be acknowledged without any stricter approaches that set out concrete and substantial set of activities. Second challenge, for the environmental governance of the BRI is to address tele couplings.

The Chinese government is taking a functioning, yet delicate way to deal with the environmental governance of the BRI. China utilizes the BRI as a stage to introduce itself as the rule-maker/rule-taker in global ecological administration as it further mobilizes existing environmental governance organisations and assembles new ones. Be that as it may, the environmental stability of the BRI doesn’t just rely on the environmental governance endeavours of Chinese actors, however, strikingly on the implementation, checking, and authorization of environmental laws and guidelines in BRI host nations. Finally, and most importantly the most significant errand for future research is to exactly explore whether environmental standards or norms be subject to California or Shanghai effects.

References

Callahan, William A. China dreams: 20 visions of China’s future Oxford University Press, 2013, p. 1

Adolph, C., Quince, V., & Prakash, A. (2017). The Shanghai effect: Do exports to China affect labor practices in Africa? World Development, 89, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.05.0091

Andrews-Speed, P., & Zhang, S. (2018). China as a low-carbon energy leader: Successes and limitations. Journal of Asian Energy Studies, 2(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.24112/jaes.02010123

Abbott, K. W. (2017). Orchestration: Strategic ordering in polycentric climate governance. In A. Jordan, D. Huitema, H. Van Asselt, & J. Forster (Eds.), Governing climate change (pp. 188–209). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108284646.01221

Cefic 2011 Cefic (2011) Guidelines for Measuring and Managing CO2 Emission from Freight Transport Operations, http://www.cefic.org/Documents/RESOURCES/Guidelines/Transport-and-Logistics/Best%20Practice%20Guidelines%20-%20General%20Guidelines/Cefic-ECTA%20Guidelines%20for%20measuring%20and%20managing%20CO2%20emissions%20from%20transport%20operations%20Final%2030.03.2011.pdf?epslanguage=eni

Randrianarisoa, Laingo M., Anming Zhang, Hangjun Yang, Andrew Yuen, and Waiman Cheung. “How ‘belt’and ‘road’are related economically: modelling and policy implications.” Maritime Policy & Management 48, no. 3 (2021): 432-460.

Cockburn , Henry. “China’s $8 Trillion ‘Silk Road’ Construction Programme ‘Riskiest Environmental Project in History’.” The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media, May 20, 2018. https://www.independent.co.uk/climate-change/news/china-belt-and-road-initiative-silk-route-cost-environment-damage-a8354256.html.

“Decarbonizing the Belt and Road Initiative: A Green Finance Roadmap.” Vivid Economics. Accessed October 1, 2021. https://www.vivideconomics.com/casestudy/decarbonizing-the-belt-and-road-initiative-a-green-finance-roadmap/.

Ascensão, F.; Fahrig, L.; Clevenger, A.P.; Corlett, R.T.; Jaeger, J.A.G.; Laurance, W.F.; Pereira, H.M. Environmental challenges for the Belt and Road Initiative. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 206–209.

Teo, Hoong C., Alex M. Lechner, Grant W. Walton, Faith K.S. Chan, Ali Cheshmehzangi, May Tan-Mullins, Hing K. Chan, Troy Sternberg, and Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz. 2019. “Environmental Impacts of Infrastructure Development under the Belt and Road Initiative” Environments 6, no. 6: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6060072

Feature Image Credit: USC US-China Institute

Map Credit: Brookings Institution

The rise of East Asia and South-East Asia is inevitable – unless there would be World War III in this region. Whereas World War I was fought by the powers located at the shore of the North-Atlantic, World War II by those of the North-Atlantic and North-Pacific, World War III would be fought by those powers solely at the North-Pacific and the Indian Ocean. Are there lessons to be learned from the devastating conduct and outcome of World War I for our times? Is there only one lesson to be learned – that you can learn nothing from history? Or are we doomed to repeat history if we don’t learn anything from it? History will not repeat itself precisely, but wars repeatedly occur throughout history, even great wars. We are living in an age in which a war between the great powers is viewed as unlikely because it seems to be in no one’s interest, as the outcome of such a war would be so devastating that each party would do the utmost to avoid it. Rationality seems to dominate the assumptions and way of thinking in our times. But no war would have been waged if the losing side, or even both sides, would have known the outcome in advance.

The rise of East Asia and South-East Asia is inevitable – unless there would be World War III in this region. Whereas World War I was fought by the powers located at the shore of the North-Atlantic, World War II by those of the North-Atlantic and North-Pacific, World War III would be fought by those powers solely at the North-Pacific and the Indian Ocean. Are there lessons to be learned from the devastating conduct and outcome of World War I for our times? Is there only one lesson to be learned – that you can learn nothing from history? Or are we doomed to repeat history if we don’t learn anything from it? History will not repeat itself precisely, but wars repeatedly occur throughout history, even great wars. We are living in an age in which a war between the great powers is viewed as unlikely because it seems to be in no one’s interest, as the outcome of such a war would be so devastating that each party would do the utmost to avoid it. Rationality seems to dominate the assumptions and way of thinking in our times. But no war would have been waged if the losing side, or even both sides, would have known the outcome in advance.