Abstract

The Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 has drastically changed both the internal situation in the Russian Federation (RF) and the country’s relationship with the international community. The impact of these developments is multidimensional and has a significant human dimension, including the formation of new migration flows marked by high shares of young people, males, and members of various elite groups. The elite migrant flow generally includes four major categories of migrants: academic personnel, highly skilled workers (including representatives of professional, business, creative, and athletic elites), students, and so-called investment migrants.

Economic Impact

Shrinking economic output1 and the withdrawal of numerous transnational companies from the RF have threatened the jobs and livelihoods of a large segment of the Russian population, hurting first and foremost its elite segments. Indeed, the introduction of new sanctions cut the long-term international ties established in the economic, political, academic, artistic, and athletic spheres, to name just a few, impacting the lives of millions of people, chief among them the representatives of various professional, business, academic, cultural, and athletic elites.

This negative impact has been aggravated by both the transborder transfers of transnational corporations’ offices and the flight of numerous Russian businesses, as well as individual enterpreneurs, to locations outside the RF. These movements, mostly economically and professionally motivated, have been supplemented by the emigration of people opposing the war as a matter of principle.

Second Wave Exceeds First

The second wave of emigration, significantly larger than the first, formed as a direct consequence of the declaration by Russian President Vladimir Putin on September 21 of a 300,000-strong “partial” mobilization and the subsequent announcement by RF Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu that up to 25 million Russian citizens might be eligible for mobilization orders—an announcement that de facto involved in the war the majority of the RF’s population (between the potential reservists and their family members). These developments and the subsequent mishandling of the mobilization process, marked by disorganization and numerous widely reported instances of corruption and abuse, acted as additional push factors of migration, which took on an increasingly politicized character.

Thus, the migration flow in 2022 has essentially consisted of two—separate and consecutive—subflows. These are far from the only large-scale population movements in post-Soviet Russian history: they follow the “brain drain” of the 1990s and the smaller in scale but consistent population movements of the first two decades of the current century. Yet there are huge differences between the current developments and previous trends.

Historical Perspective

Russia saw its position in the global migration chain change drastically after the dissolution of the USSR in 1991. In its aftermath, the RF quickly became an active participant in the globalization process, following the general trend among those states that were previously the centers of multinational empires: the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Belgium, and especially the territorially contiguous empires (Germany, Austria, and Turkey) have received, since their empires’ collapse, considerable migrant flows of two major types. The first wave was the permanent—and mostly politically motivated—return migration of the representatives of the former “imperial” nation to their ethnic homelands (the Britons, French, Spaniards, Turks, etc.). They were soon followed by migrants from developing countries—primarily the former colonies of the metropole. These were people who spoke its language, knew its culture, and could rely on the support there of their long-established ethnic diasporas.

As a result, Russia—previously one of the most isolated countries in the world—quickly became, after 1991, the center of a vast Eurasian migration system that was one of the four largest in the world (alongside those in North America; Western Europe; and the Middle East, centered on the Persian Gulf). By 2010, more than 12 million RF residents (about 8.5% of its population) had been born outside the country. In 2015, Russia ranked third in the world—after India and Mexico—in terms of its number of emigrants: 10.5 million.2 While most of these migrants moved within the post-Soviet space, in 1991–2005 alone, more than 1.3 million Russian citizens obtained permits for permanent emigration to the West.3 Overall, the number of those who were born in Russia but currently live in countries outside the former USSR is estimated at approximately 3,000,000.4

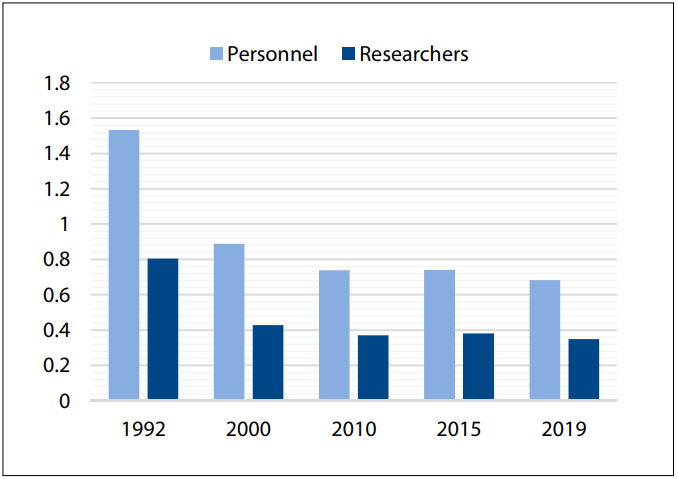

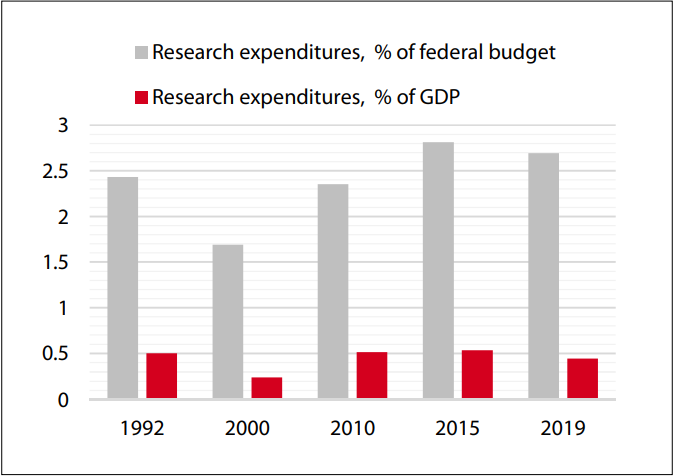

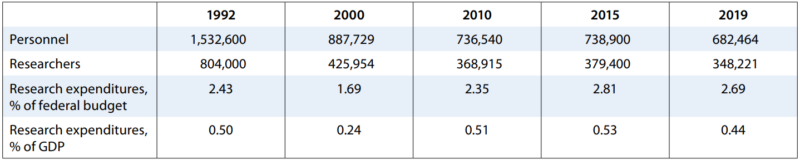

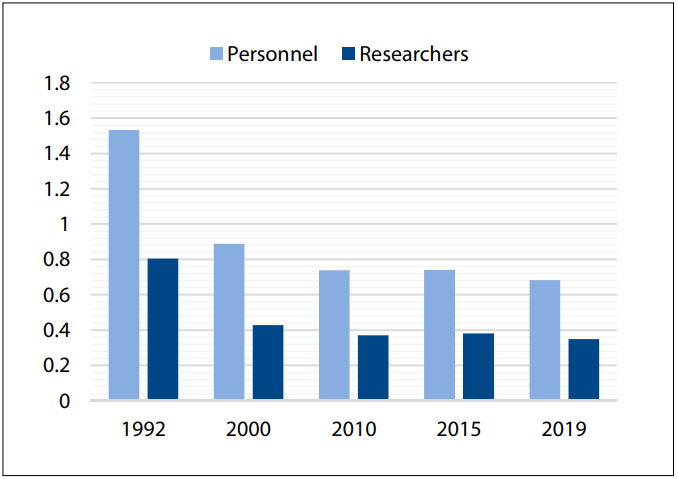

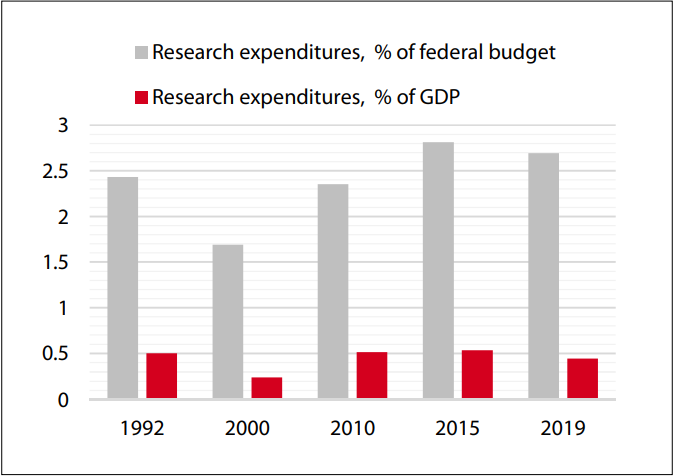

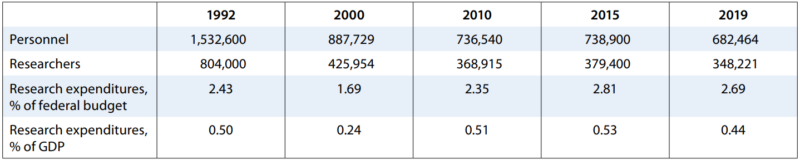

This flow was generated by both the “pull” and “push” factors of migration. In the case of emigration outside the post-Soviet region, an important role was played by the liberalization of the migration regime and the emergence of opportunities to work and study abroad; higher living standards; prospects for professional growth; and the genearally welcoming atmosphere for Russian scholars, students, and professionals at that time. “Push” factors included the economic and political instability in Russia, specifically the rapid degradation of Russian state-run industry and of the academic sphere. Research expenditure as a share of Russian GDP was 0.50% in 1992 and 0.24% in 2000 (representing 2.43% and 1.69% of the federal budget, respectively). During this period (1992–2000), the number of those employed by the academic institutions fell from 1,532,000 to 887,729 (a 42% drop), while the number of researchers declined from 804,000 to 425,954 (a 47% drop).5

With the economic and political stabilization of the early Putin years, budgetary expenditures increased, peaking in 2015 at 2.81% of the federal budget (0.53% of GDP).

These processes led to the formation of significant elite Russian diasporas in the major receiving countries. Already by 2010–11, more than 660,000 university educated Russians were living abroad, putting the RF into the category of states with large elite diasporas (300,000 to 1,000,000 migrants with a university degree)—along with such countries as Mexico, South Korea, Vietnam, Iran, Taiwan, Morocco, and Colombia.6 Of particular importance was the massive emigration of Russian scholars and educators: I previously estimated the size of this elite diaspora at about 300,000–350,000 in 2012, including, as of 2015, approximately 56,000 students studying abroad. The academic flow was heavily dominated by basic and technical sciences experts, while specialists in social sciences and the humanities accounted for just 6.1% of the total in 2002–03.7 The flow was also skewed geographically toward the two highly developed Global North regions of North America and Western Europe, which respectively accounted for 30.4% and 42.4% of the intellectual migration flow. The largest receiving countries were the United States (28.7%) and Germany (19%); these two states also held first and second place, respectively, among receiving countries in practically all academic subfields.8

With the economic and political stabilization of the early Putin years, budgetary expenditures increased, peaking in 2015 at 2.81% of the federal budget (0.53% of GDP). This served to slow down the academic personnel decline and the elite outflow: between 2000 and 2019, the number of those employed in the academic sphere declined from 887,729 to 682,464 (or by 23.1%), while the number of researchers fell from 425,954 to 348,221 (or by 18.2%9 —see Figures 1a and 1b below and Table 1 on p. 11). While the number of Russian students studying abroad remained relatively stable at 50,000–60,000, the RF during that period rebuilt its position as one of the leading hubs for international students—ranking sixth in the world behind the US, the UK, Australia, France, and Germany.10 Their numbers grew steadily, from 153,800 in 2010/2011 to 298,000 in the 2019/2020 academic year.11

Figure 1a: Russian R&D Dynamics, 1992–2019: Personnel (mln.)

Figure 1b: Russian R&D Dynamics, 1992–2019: Expenditures

Source: Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, “Rossiia v Tsifrakh—2020,” 2021, https://gks.ru/bgd/regl/b20_11/Main.htm; Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, Rossiiskii Statisticheskii ezhegodnik 2009 (Moscow, 2009), 543, 553; Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, Rossiiskii Statisticheskii ezhegodnik 2020 (Moscow, 2020), 495–6, https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/Ejegodnik_2020.pdf; Gosudarstvennyi komitet Rossiiskoi Federatsii po statistike, Rossiiskii Statisticheskii ezhegodnik 2003 (Moscow, 2003), 531.

Russia, while losing its elite migrants to the more developed countries of the Global North, was at least partially substituting for their loss with immigration from less developed states, primarily those in the post-Soviet space.

Overall, it could be concluded that Russia transformed in the early 2000s from the country in deep economic and social crisis—and source of massive elite outflows— that it had been in the 1990s into a state with a moderate level of development that played multiple roles in the world migration chain: both sending and receiving migrants as well as acting as a migrant transit country. Russia, while losing its elite migrants to the more developed countries of the Global North, was at least partially substituting for their loss with immigration from less developed states, primarily those in the post-Soviet space. The impact of the “pull” factors of migration increased, while that of the “push” factors decreased, at least in relative terms.

After the Invasion

This multiplicity of roles was for the most part retained by the RF after the first invasion of Ukraine in 2014 (even under the conditions of the expanding sanctions

regime) and during the general decline of migration activity worldwide as a result of COVID-19 restrictions. Yet the events of 2022 have drastically changed the migration environment, returning it to a crisis level, with the “push” factors of migration (such as the deteriorating political situation, sharp disagreements with governmental policies among certain segments of society, the unwillingness of many to serve in the RF military, the fear of losing jobs and sources of income, etc.) coming to the forefront.

When it comes to the contrast between current migration flows and previous post-Soviet flows, the following points should be noted:

- The 2022 migration waves are defined primarily by “push” factors, which have frequently forced people to leave even in the absence of adequate preparation

(previous experience of work or study abroad, personal or professional networks) or clear prospects in destination countries.

- Migration in 2022 is frequently directed toward smaller and economically weaker countries than in the 1990s, including those in Eastern Europe, the post-Soviet space (Central Asia, the Caucasus), and the Persian Gulf, as well as Turkey and Mongolia. This may lead to the reversal of the trends that have dominated (especially elite) migration patterns in Central Eurasia for the last three decades. This reversal, which has important symbolic value, may create significant long-term labor-market and demographic problems for the RF.

- In contrast to previous migration waves, the current ones are marked by their hectic, spontaneous character and the heavy presence in the flow of young people working in the IT and business sectors, who are relatively flexible and could either seek jobs or create private-sector businesses. At the same time, there is also a significant share of people, especially within the academic bloc, who hold Humanities and Social Sciences degrees and have very limited prospects of finding jobs that correspond to their qualifications. Thus, even under the current crisis conditions, substantial return migration can be expected.

- In 2022, movement is further complicated by the heritage of the COVID-19 pandemic and the new limitations resulting from the 2022 sanctions— these are related to the blocking of RF-issued credit cards, the break-up of direct transportation links with most European countries, complications with getting visas, and frequently prohibitive airfare rates. An additional complication is presented by the recent proposals, in a number of Western countries, to arrest RF citizens or confiscate their property.

- A particular feature of the 2022 flows has been their “explosive,” emergency character, marked by very high intensity in the initial weeks and a relatively

quick decline thereafter.

There also exist visible differences between the flow that followed the developments of February 2022 and the flow that followed the events of September 2022. In particular,

- A noticeable discrepancy exists in terms of their scale and gender structure. The first flow was on the order of 100,000–150,000 people and was relatively balanced in gender terms, frequently including whole families with children. The second, which followed Putin’s mobilization announcement, has been heavily dominated by young males. This in itself poses significant problems for Russia’s demographic and economic future.

- The first flow was directed, first and foremost, toward all the countries neighboring Russia. The current one, meanwhile, is taking place under the conditions of

changing public attitudes and governmental policies toward RF citizens, even those who oppose Putin’s actions. This dynamic could lead to general change in the direction of migration flows.

- The flow of the first half of 2022 was marked by heavy presence of foreign citizens and people with dual citizenship or other legal status, who moved to the countries where they held such status. The participants in the current flow, who are primarily RF citizens, face additional legal problems in receiving countries by comparison.

- The original flow included large numbers of people who worked in the RF offices of transnational companies that relocated, along with their personnel, to other countries. These people had some social guarantees, had experience of work for a TNC, and could rely on their companies’ support. People emigrating in the newest waves lack these opportunities.

- The large-scale arrival of migrants in countries with relatively weak infrastructure and limited economic capacity (the states of the Baltic, the Transcaucasus, and Central Asia) has put significant pressure on these states’ economies and labor markets. Successive waves of migrants will therefore increasingly encounter competition, economic hardship, and negative public attitudes.

While there exist huge discrepancies in the estimates of migration flows made by various entities—both governmental agencies and non-governmental organization —in Russia as well as the receiving states, it is clear that the most recent flow has been much larger than the one in the first half of 2022. The most frequently cited figure is on the order of 700,000 people.12 How-ever, a major problem is that most estimates rely on the statistical data of the national border guard services, which report the number of border crossings in a particular period of time without accounting for repeat crossings, return migration, movement to the third countries, “shuttle” activities, irregular migration, etc.13 Because of these limitations, it is likely that the overall number of migrants in the “second wave” is currently in the range of 350,000–450,000. Thus, the overall number of migrants who have left the RF in the two urgent and chaotic waves of 2022 can be estimated at about 500,000. Even this figure represents a substantial potential loss for a country—particularly one like Russia that was already experiencing population decline.14 It is a special concern considering the skewed gender, age, and qualification structure of those currently leaving the RF.

Table 1: Russian R&D Dynamics, 1992–2019

Source: Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, “Rossiia v Tsifrakh—2020,” 2021, https://gks.ru/bgd/regl/b20_11/Main.htm; Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, Rossiiskii Statisticheskii ezhegodnik 2009 (Moscow, 2009), 543, 553; Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, Rossiiskii Statisticheskii ezhegodnik 2020 (Moscow, 2020), 495–6, https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/Ejegodnik_2020.pdf; Gosudarstvennyi komitet Rossiiskoi Federatsii po statistike, Rossiiskii Statisticheskii ezhegodnik 2003 (Moscow, 2003), 531.

While these factors represent some very important arguments for putting an immediate end to the military action, it is clear that demographic, labor market, and socio-economic considerations are of minor significance for Vladimir Putin. More than that, following Alexander Lukashenka’s example in Belarus following the protests there in 2020, the RF leadership could perceive the current migration outflows as politically useful, ridding it of opponents to the war and regime and further weakening the country’s civil society. Thus, the disastrous 2022 policies might continue, aggravating both the domestic socio-economic situation and the RF’s position in the world.

References:

- In particular, Russia’s industrial output in September 2022 was 9% of that in September 2021 (Federal’naia Sluzhba Gosudarstvennoi Statistiki, “Operativnye Pokazateli,” 2022, https://rosstat.gov.ru/).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Trends in International Migration Stock: The 2015 Revi- sion (New York: United Nations, 2015).

- Anatolii Vishnevskii, , Naseleniie Rossii 2003-2004: Odinnadtsatyi-dvenadtsatyi ezhegodnyi demograficheskii doklad (Moscow: Nauka, 2006), 325.

- “‘Meduza’ ob emigratsii iz Rossii,” Demoscope 945–6 (17–30 May 2022), http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2022/0945/gazeta01.php.

- Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, “Rossiia v Tsifrakh—2020,” 2021, https://gks.ru/bgd/regl/b20_11/Main.htm; Gosudarst- vennyi komitet Rossiiskoi Federatsii po statistike, Rossiiskii Statisticheskii ezhegodnik 2003 (Moscow, 2003),

- This group is second to that of countries with extra-large diasporas (more than 1,000,000 people). As of 2015, that group included India (2,080,000), China (1,655,000), the Philippines, the UK, and See Irina Dezhina, Evgeny Kuznetsov, and Andrei Korobkov, Raz- vitie Sotrudnichestva s Russkoiazychnoi Diasporoi: Opyt, Problemy, Perspektivy (Moscow, 2015), http://russiancouncil.ru/upload/Report- Scidiaspora-23-Rus.pdf, 18.

- V. Korobkov and Zh. A. Zaionchkovskaya, “Russian Brain Drain: Myths and Reality,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 45, no. 3-4 (September-December 2012): 332.

- , 335–6. See also Andrei Korobkov, “Russian Academic Diaspora: Its Scale, Dynamics, Structural Characteristics, and Ties to the RF,” in Migration from the Newly Independent States: 25 Years After the Collapse of the USSR, ed. Mikhail Denisenko, Salvatore Strozza, and Matthew Light (New York: Springer, 2020), 299–322.

- Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, “Rossiia v Tsifrakh—2020;” Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, Rossiiskii Stat- isticheskii ezhegodnik 2020 (Moscow, 2020), 495–6, https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/Ejegodnik_2020.pdf.

- “Mezhdunarodnye studenty,” Unipage, 2019, https://unipage.net/ru/student_statistics.

- Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, “Rossiia v Tsifrakh—2020;” Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, Rossiiskii Stat- isticheskii ezhegodnik 2020, 206, https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/Ejegodnik_2020.pdf.

- See, for instance, “Forbes: posle ob”iavleniia mobilizatsii Rossiiu pokinuli primerno 700 chelovek,” Kommersant, October 4, 2022, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5594533.

- For example, the Interior Ministry of Kazakhstan reported at the beginning of October that in the wake of the mobilization announcement by Vladimir Putin on September 21, 2022, more than 200,000 people had crossed the country’s border with Russia, of whom just seven had been deported back to the At the same time, this report noted that 147,000 of them had already left Kazakhstan within a period of less than two weeks. See Mikhail Rodionov, “V Kazakhstan s 21 sentiabria v”ekhali bolee 200 tysiach rossiian. Deportirovali semerykh,” Gazeta. ru, October 4 2022, https://www.gazeta.ru/politics/2022/10/04/15571807.shtml.

- In 2019, the fertility rate in Russia was 1.504. See Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, “Rossiia v Tsifrakh—2020;” Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki, Rossiiskii Statisticheskii ezhegodnik 2020, 103.

This article was originally published at the Center for Security Studies (CSS)

Featured Image Credits: Politico

Instead of using the breathing space provided by the lockdown to bolster local health systems, the central government left state authorities to manage as best they could with minimal and inadequate resources. And when the resulting economic disaster threatened to spiral out of control, the government eased restrictions to “unlock” the economy even as the number of cases mounted, thereby putting more people at risk.