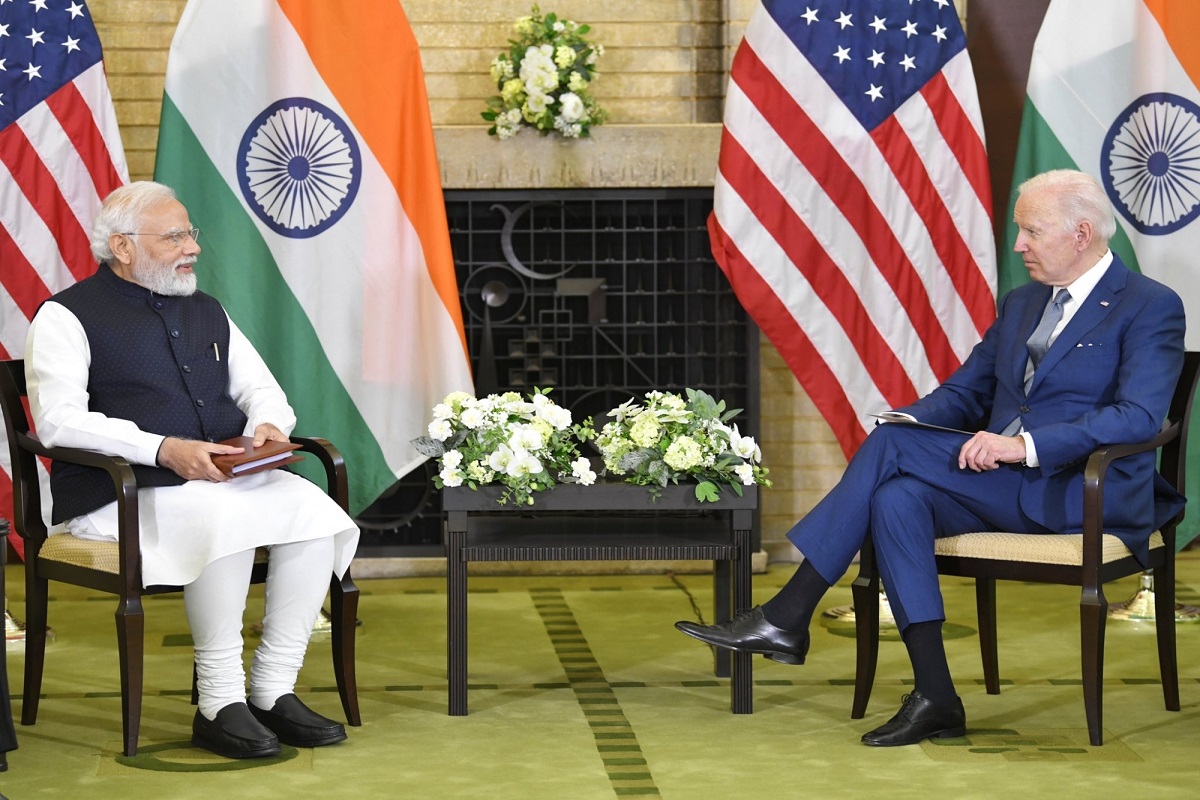

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s state visit to the USA resulted in four significant agreements and the visit is hailed as one of very important gains for India and Indo-US strategic partnership. The focus has been on defence industrial and technology partnership. Media and many strategic experts are seeing the agreements as major breakthroughs for technology transfers to India, reflecting a very superficial analysis and a lack of understanding of what really entails technology transfer. Professor Arun Kumar sees these agreements as a sign of India’s technological weakness and USA’s smart manoeuvring to leverage India for long-term defence and technology client. The visit has yielded major business gains for USA’s military industrial complex and the silicon valley. Post the euphoria of the visit, Arun Kumar says its time for India to carefully evaluate the relevant technology and strategic policy angles.

The Indo-US joint statement issued a few days back says that the two governments will “facilitate greater technology sharing, co-development and co-production opportunities between the US and the Indian industry, government and academic institutions.” This has been hailed as the creation of a new technology bridge that will reshape relations between the two countries

General Electric (GE) is offering to give 80% of the technology required for the F414 jet engine, which will be co-produced with Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL). In 2012, when the negotiations had started, GE had offered India 58%. India needs this engine for the Light Combat Aircraft Mark 2 (LCA Mk2) jets.

The Indian Air Force has been using LCA Mk1A but is not particularly happy with it. It asked for improvements in it. Kaveri, the indigenous engine for the LCA under development since 1986, has not been successful. The engine development has failed to reach the first flight.

So, India has been using the F404 engine in the LCA Mk1, which is 40 years old. The F414 is also a 30-year-old vintage engine. GE is said to be offering 12 key technologies required in modern jet engine manufacturing which India has not been able to master over the last 40 years. The US has moved on to more powerful fighter jet engines with newer technologies, like the Pratt & Whitney F135 and GE XA100.

India is being allowed into the US-led critical mineral club. It will acquire the highly rated MQ-9B high-altitude long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicles. Micron Technologies will set up a semiconductor assembly and test facility in Gujarat by 2024, where it is hoped that the chips will eventually be manufactured. The investment deal of $2.75 billion is sweetened with the Union government giving 50% and Gujarat contributing 20%. India is also being allowed into the US-led critical mineral club.

There will be cooperation in space exploration and India will join the US-led Artemis Accords. ISRO and NASA will collaborate and an Indian astronaut will be sent to the International Space Station. INDUS-X will be launched for joint innovation in defence technologies. Global universities will be enabled to set up campuses in each other’s countries, whatever it may imply for atmanirbharta.

What does it amount to?

The list is impressive. But, is it not one-sided, with India getting technologies it has not been able to develop by itself.

Though the latest technology is not being given by the US, what is offered is superior to what India currently has. So, it is not just optics. But the real test will be how much India’s technological capability will get upgraded.

Discussing the New Economic Policies launched in 1991, the diplomat got riled at my complaining that the US was offering us potato chips and fizz drinks but not high technology, and shouted, “Technology is a house we have built and we will never let you enter it.”

What is being offered is a far cry from what one senior US diplomat had told me at a dinner in 1992. Discussing the New Economic Policies launched in 1991, the diplomat got riled at my complaining that the US was offering us potato chips and fizz drinks but not high technology, and shouted, “Technology is a house we have built and we will never let you enter it.”

Everyone present there was stunned, but that was the reality.

The issue is, does making a product in India mean a transfer of technology to Indians? Will it enable India to develop the next level of technology?

India has assembled and produced MiG-21 jets since the 1960s and Su-30MKI jets since the 1990s. But most critical parts of the Su-30 come from Russia. India set up the Mishra Dhatu Nigam in 1973 to produce the critical alloys needed and production started in 1982, but self-sufficiency in critical alloys has not been achieved.

So, production using borrowed technology does not mean absorption and development of the technology. Technology development requires ‘know-how’ and ‘know-why’.

When an item is produced, we can see how it is produced and then copy that. But we also need to know how it is being done and importantly, why something is being done in a certain way. Advanced technology owners don’t share this knowledge with others.

Technology is a moving frontier

There are three levels of technology at any given point in time – high, intermediate, and low.

The high technology of yesterday becomes the intermediate technology of today and the low technology of tomorrow. So, if India now produces what the advanced countries produced in the 1950s, it produces the low-technology products of today (say, coal and bicycles).

If India produces what was produced in the advanced countries in the 1980s (say, cars and colour TV), it produces the intermediate technology products of today. It is not to say that some high technology is not used in low and intermediate-technology production.

The high technologies of today are aerospace, nanotechnology, AI, microchips and so on. India is lagging behind in these technologies, like in producing passenger aircraft, sending people into space, making microchips, quantum computing, and so on.

The advanced countries do not part with these technologies. The World Trade Organisation, with its provisions for TRIPS and TRIMS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights and Trade-Related Investment Measures), consolidated the hold of advanced countries on intermediate and low technologies that can be acquired by paying royalties. But high technology is closely held and not shared.

Advancements in technology

So, how can nations that lag behind in technology catch up with advanced nations? The Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow pointed to ‘learning by doing’ – the idea that in the process of production, one learns.

So, the use of a product does not automatically lead to the capacity to produce it, unless the technology is absorbed and developed. That requires R&D.

Schumpeter suggested that technology moves through stages of invention, innovation and adaptation. So, the use of a product does not automatically lead to the capacity to produce it, unless the technology is absorbed and developed. That requires R&D.

Flying the latest Airbus A321neo does not mean we can produce it. Hundreds of MiG-21 and Su-30 have been produced in India. But we have not been able to produce fighter jet engines, and India’s Kaveri engine is not yet successful. We routinely use laptops and mobile phones, and they are also assembled in India, but it does not mean that we can produce microchips or hard disks.

Enormous resources are required to do R&D for advanced technologies and to produce them at an industrial scale. It requires a whole environment which is often missing in developing countries and certainly in India.

Enormous resources are required to do R&D for advanced technologies and to produce them at an industrial scale. It requires a whole environment which is often missing in developing countries and certainly in India.

Production at an experimental level can take place. In 1973, I produced epitaxial thin films for my graduate work. But producing them at an industrial scale is a different ballgame. Experts have been brought from the US, but that has not helped since high technology is now largely a collective endeavour.

For more complex technologies, say, aerospace or complex software, there is ‘learning by using’. When an aircraft crashes or malware infects software, it is the producer who learns from the failure, not the user. Again, the R&D environment is important.

In brief, using a product does not mean we can produce it. Further, producing some items does not mean that we can develop them further. Both require R&D capabilities, which thrive in a culture of research. That is why developing countries suffer from the ‘disadvantage of a late start’.

A need for a focus on research and development

R&D culture thrives when innovation is encouraged. Government policies are crucial since they determine whether the free flow of ideas is enabled or not. Also of crucial importance is whether thought leaders or sycophants are appointed to lead institutions, whether criticism is welcomed or suppressed, and whether the government changes its policies often under pressure from vested interests.

Unstable policies increase the risk of doing research, thereby undermining it and dissuading the industry. The result is the repeated import of technology.

The software policy of 1987, by opening the sector up to international firms, undermined whatever little research was being carried out then and turned most companies in the field into importers of foreign products, and later into manpower suppliers. Some of these companies became highly profitable, but have they produced any world-class software that is used in daily life?

Expenditure on R&D is an indication of the priority accorded to it. India spends a lowly 0.75% of its GDP on R&D. Neither the government nor the private sector prioritises it. Businesses find it easier to manipulate policies using cronyism. Those who are close to the rulers do not need to innovate, while others know that they will lose out. So, neither focus on R&D.

Innovation also depends on the availability of associated technologies – it creates an environment. An example is Silicon Valley, which has been at the forefront of innovation. It has also happened around universities where a lot of research capabilities have developed and synergy between business and academia becomes possible.

This requires both parties to be attuned to research. In India, around some of the best-known universities like Delhi University, Allahabad University and Jawaharlal Nehru University, coaching institutions have mushroomed and not innovative businesses. None of these institutions are producing any great research, nor do businesses require research if they can import technology.

A feudal setup

Technology is an idea. In India, most authority figures don’t like being questioned. For instance, bright students asking questions are seen as troublemakers in most schools. The emphasis is largely on completing coursework for examinations. Learning is by rote, with most students unable to absorb the material taught.

So, most examinations have standard questions requiring reproduction of what is taught in the class, rather than application of what is learned. My students at JNU pleaded against open-book exams. Our class of physics in 1967 had toppers from various higher secondary boards. We chose physics over IIT. We rebelled against such teaching and initiated reform, but ultimately most of us left physics – a huge loss to the subject.

Advances in knowledge require critiquing its existing state – that is, by challenging the orthodoxy and status quo. So, the creative independent thinkers who generate socially relevant knowledge also challenge the authorities at their institutions and get characterised as troublemakers. The authorities largely curb autonomy within the institution and that curtails innovativeness.

In brief, dissent – which is the essence of knowledge generation – is treated as a malaise to be eliminated. These are the manifestations of a feudal and hierarchical society which limits the advancement of ideas. Another crucial aspect of generating ideas is learning to accept failure. The Michelson–Morley experiment was successful in proving that there is no aether only after hundreds of failed experiments.

Conclusion

The willingness of the US to provide India with some technology without expecting reciprocity is gratifying. Such magnanimity has not been shown earlier and it is obviously for political (strategic) reasons. The asymmetry underlines our inability to develop technology on our own. The US is not giving India cutting-edge technologies that could make us a Vishwaguru.

India needs to address its weakness in R&D. As in the past, co-producing a jet engine, flying drones or packaging and testing chips will not get us to the next level of technology, and we will remain dependent on imports later on.

This can be corrected only through a fundamental change in our R&D culture that would enable technology absorption and development. That would require granting autonomy to academia and getting out of the feudal mindset that presently undermines scientific temper and hobbles our system of education.

This article was published earlier in thewire.in

Feature Image Credit: thestatesman.com