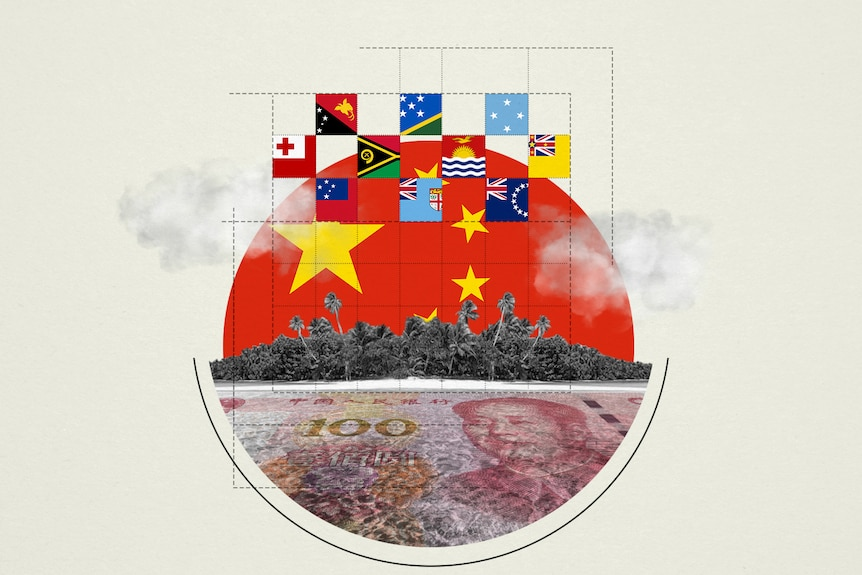

The Pacific Island Countries (PICs) have received increasing attention recently as they continue to be centres of geopolitical tension between China and western powers – the USA, Australia, and New Zealand. The island nations are generally grouped into three distinct regions, namely – Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia, on the basis of their physical and human geography. They possess some of the largest Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) in the world spanning about 30 million sq km (11.6 million sq miles) of the ocean despite their small size and limited population.

The Chinese efforts to secure a strong military presence in the Pacific Island Countries could not only enable it to achieve ‘Blue Navy Status’ but also counter this overwhelming US military presence surrounding it.

The economic potential of these Exclusive Economic Zones, which are rich in fisheries, energy, minerals and other marine resources, is so immense that these nations prefer to be regarded as the Big Ocean States, rather than the Small Island States. In the past, the islands have functioned as launchpads and laboratories, playing crucial roles in power rivalries due to their location and geography¹. With China endeavouring to spread its power and influence to achieve Great Power status, it is natural that it set its sights on areas which have been traditionally dominated by Western powers. Increased Chinese presence in the Pacific Islands is aimed at ending the United States unchallenged influence in the region and to enable suitable backups in a potential conflict over Taiwan. The US presently has 53 overseas military bases across Japan and South Korea, in close proximity to the Chinese mainland as opposed to China’s only overseas military base in Djibouti. Thus, the Chinese efforts to secure a strong military presence in the Pacific Island Countries could not only enable it to achieve ‘Blue Navy Status’ but also counter this overwhelming US military presence surrounding it.

Economic Factors and China’s Strategy

The economic attractiveness of the Pacific Islands also includes access to its trade and shipping routes. On the diplomatic front, these nations tend to serve as a vote bank at forums like the United Nations and can help Beijing in its ambition to further isolate Taiwan. Additionally, stronger relations would help in advancing China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative while also enhancing its image as a reliable partner and viable alternative to other major powers, especially the US and Australia.

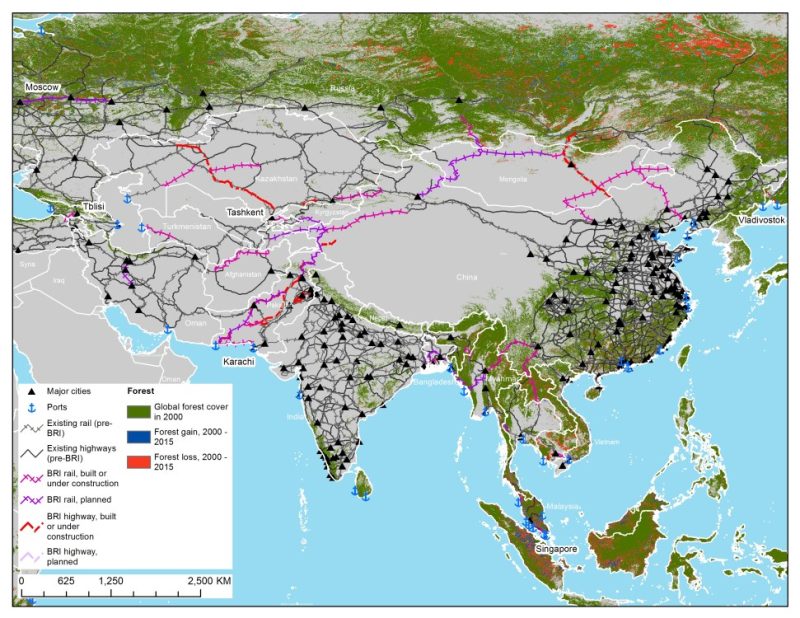

China has had ties with the Pacific Islands since the 1970s but many island nations’ official diplomatic recognition of Taiwan continued to be a major hurdle throughout these years. Through continued economic assistance, China has succeeded in getting diplomatic recognition from 10 out of the 14 Pacific Islands. Presently, only four countries namely Tuvalu, Palau, Marshall Islands and Nauru recognise Taiwan, with Kiribati being the latest nation to withdraw its recognition in September 2019. The success of the Chinese approach can be seen in the fact that they have successfully secured Belt and Road cooperation MOUs with all the 10 PICs and have signed the Belt and Road cooperation plans with Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Vanuatu. As per the fact sheet released by the Chinese government, China and the PICs have continued to expand cooperation in more than 20 different areas, which include trade, investment, ocean affairs, environmental protection, disaster prevention and mitigation, poverty alleviation, health care, education, tourism, sports and culture.

Significant progress in China – PIC relations was seen with the establishment of the China-Pacific Island Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Forum in 2001, which functions as the highest-level dialogue mechanism between the countries in the fields of economy and trade. In November 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping paid a state visit to Fiji where he held a group meeting with the PIC head of states. An agreement was signed to establish a strategic partnership and these ties were elevated to a comprehensive strategic partnership featuring mutual respect and common development in November 2018, during President Xi Jinping’s visit to PNG. One of the more recent developments is the China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting held in October 2021, which resulted in the Joint Statement of China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting.

Attention towards climate change action has given China a strong foothold amidst rising frustration among the PICs about the Western powers’ proclivity to focus on geopolitical concerns without sparing sufficient attention to the island country’s paramount needs and concerns.

The major success of the Chinese strategy with regards to the Pacific Island nations can be found in their harnessing of pressing issues like climate change, environment, agricultural development, infrastructure and rising sea levels which have been largely neglected by traditional powers. From providing yearly financial assistance to the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) since 1998, the Chinese government has taken efforts to address and assist the PICs in tackling climate change and achieving sustainable development. April 2022 saw the launch of the China-Pacific Island Countries Climate Change Cooperation Centre in the Shandong Province of China. The Chinese have strengthened renewable energy cooperation with the PICs and have facilitated the construction of hydro-power stations in countries like PNG and Fiji. This attention towards climate change action has given China a strong foothold amidst rising frustration among the PICs about the Western powers’ proclivity to focus on geopolitical concerns without sparing sufficient attention to the island country’s paramount needs and concerns.

Infrastructure Strategy – BRI Model

Infrastructure development has been another avenue where the Chinese have shown significant enthusiasm. Several important connectivity projects have been executed in the PICs including the Independence Boulevard in PNG, Malakula island highway in Vanuatu, renovation of Tonga national road, and Pohnpei highway in Micronesia. Aside from providing much needed support in a variety of fields, the Chinese approach to the Pacific islands as a collective entity has helped acknowledge the group as having a combined identity and decision-making capability. Addressing issues which have only been previously discussed on a bilateral basis also provides the PIC with enhanced political strength and purpose, because despite all their differences, most of the countries share similar needs and requirements.

Chinese efforts to establish a strong military presence in the region were in 2018, when the Australian press reported that China had requested the right to establish a permanent military presence in Vanuatu, situated less than 2,000 kilometres from Australian territory. However, no formal agreement was drafted. The then Prime Minister of Vanuatu strongly denied that any such talks had taken place and assured the local and international community that there would be no Chinese military presence in the country. A similar report was released by the Australian press in the same year alleging that China held a keen interest in refurbishing a port on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea which had previously functioned as the site of an Allied naval base during World War II. The claims were dismissed when the PNG government contracted Australia and the United States to redevelop the port instead.

The Chinese efforts finally materialized in the form of the China – Solomon Islands Security Pact in April 2022. As per the terms of the pact, permission is granted to the Chinese navy to dock and refuel in the Solomon Islands, laying the groundwork for a facility that could be expanded over time. The pact allows the Solomon Islands to seek Chinese assistance when required to maintain social order and stability. The pact has been understood by several scholars as a way for China to establish a permanent military presence gradually under the guise of performing this role. The security pact came at a time when international attention was already on the growing closeness of China and the Pacific Island nations following the leak of two draft documents “China-Pacific Island Countries (PICs) Common Development Vision”, and “China-Pacific Islands Five-Year Action Plan on Common Development (2022-2026)” at the start of 2022.

USA’s Response

In the face of China’s rising threat, the United States released its Indo-Pacific Strategy in February 2022 which emphasized the importance of the Pacific Islands to the United States. Along with the “Partners in the Blue Pacific” initiative, it reiterated its commitment to cement itself as a dominant power in the region. However, definitive action on a large scale was taken only in late May when the Chinese Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, embarked on a 10-day visit to the region attempting to secure a comprehensive framework agreement with engagements on multiple fronts with the PICs. Although the attempt was unsuccessful, Wang, during his visit, travelled to eight countries (the Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Samoa, Fiji, Tonga, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and Timor-Leste) and held virtual meetings with three additional nations (Cook Islands, Niue and the Federated States of Micronesia), ultimately signing 52 bilateral treaties. Although the Chinese foreign minister stressed the country’s commitment and intent for long-term engagement in the region, news of the framework agreement sparked great controversy. The Pacific Island nations could not reach a unanimous decision on signing this agreement and decided to deliberate the matter at the PIF meeting. However, this decision to postpone discussions was disadvantageous to China as the PIF has membership from both New Zealand and Australia both of which were sure to put up strong opposition to the signing of this agreement. Perhaps foreseeing this, the agreement was soon withdrawn after which China immediately released a Position Paper on Mutual Respect and Common Development ² with Pacific Island Countries, which offers 15 “visions and proposals” for deepening China’s engagement in the region. The security issues (China sought to train local police forces, conduct mapping of sensitive marine areas, and play a role in the cyber security of the nations) that had caused much controversy were only mentioned briefly within the paper with much of the focus pointed notably towards political and economic issues. Wang, as part of his visit, also hosted the second round of the China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers Meeting in Fiji where he delivered the Secretary General of the Chinese Communist, Party Xi Jinping’s written remarks on China’s continued support.

Swift responses came about on May 31, when US President Biden and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern issued a joint statement that highlighted the two countries’ shared commitment to the Pacific Islands. The statement also expressed their concern over the China – Solomon Islands Security Pact and warned against “the establishment of a persistent military presence in the Pacific by a state that does not share our values or security interest.” ⁴ Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong embarked on a similar visit to Fiji, Samoa and Tonga in early June to reinforce Canberra’s commitments to its neighbours.

Despite these advancements, public response to the Chinese visit and in a broader sense, to China’s growing footprint in the region was largely negative. Domestic response in Kiribati was lukewarm due to the wariness stemming from rumours that surfaced in 2021 about China’s plans to upgrade a World War II airstrip in the country, which is likely to damage the country’s already strained fish stocks. The announcement that Fiji would become a founding member of the U.S. led Indo- Pacific Economic Framework by President Frank Bainimaram immediately prior to Wang’s visit reflected wariness about China’s future presence in the area. Additionally, despite signing the security pact, Solomon Islands Prime Minister Sogavare’s support for Beijing gave rise to worries that China would now be in a position “to prop up an unpopular regime and undermine the democratic processes in the name of maintaining social order” among his critics. However, the most vocal voice of protest was that of David Panuelo, the president of the Federated States of Micronesia, who called upon his fellow Pacific Island leaders to reject China’s offers of a comprehensive framework agreement calling it “the single-most game-changing proposed agreement in the Pacific in any of our lifetimes.” ³ The lack of transparency during Wong’s visit drew further criticism with the strict regulation of foreign journalists and ban on direct questions. It eventually led the Media Association of the Solomon Islands to issue a boycott notice to its members, urging them to skip the press event in protest of these restrictions.

Concerns have also arisen due to China’s reputation for extremely stringent terms of lending and what the West accuses as ‘debt trap’ policy. 60 percent of all Chinese loans are offered at commercial rates rather than concessional rates with extremely short repayment periods – usually less than 10 years. Additionally, the confidentiality clauses (borrowing countries cannot reveal terms of the loan provided or in some cases the very existence of the loan), stabilization clause (lender can demand immediate repayment of loan in case of significant change in the borrowing country’s laws like labour or environment policies), cross-default clause (contract can be terminated and full and immediate repayment can be demanded if the borrowing country defaults on any of its other lenders), political clause ( termination or acceleration of repayment if the borrower acts against China) as well as holding Chinese projects in the country as collateral which are characteristic of Chinese loans are also worrying. The lack of public access to the China – Solomon Islands security pact document and similar documents is also unsettling.

Demand for addressing Climatology threats and not Geopolitics

Chinese interest in the region has served as an efficient bargaining chip for the Pacific Islands to secure their key security interests.

The geopolitical competition brewing in the region has been a topic of discussion at the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF). Its members include Australia, New Zealand, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Palau, Tuvalu and Nauru in addition to the other Pacific Island Nations. Kiribati’s withdrawal from the Forum on July 9 led to debates on China’s influence on this decision among the opposition parties in the country. However, the government cited the failure to adhere to previous engagements, which in turn threatened equal respect and position accorded to the members of the forum as a reason for this move. The PIF meetings conducted between July 11 and July 14 gave ample opportunity for traditionally influential powers like the US and Australia to promise stronger support for the region. US Vice President Kamala Harris addressed the forum as a special invitee announcing two new embassies in Kiribati and the Solomon Islands. She also pledged to triple current aid levels (up to 60 million dollars per year for 10 years) to help combat illegal fishing, enhance maritime security and tackle climate change, after decades of stalled funding as well as a return of peace corps volunteers to Fiji, Tonga, Samoa and Vanuatu. Australia’s remarks ran along similar lines i.e.; pledges of greater support for the climate change agenda of its neighbours.

Chinese interest in the region has served as an efficient bargaining chip for the Pacific Islands to secure their key security interests. Using this geopolitical competition to its favour could be the way forward for these island nations whose very existence is threatened by rising sea levels. As Dame Meg Taylor, former secretary-general of the Pacific Islands Forum states, the process is already underway. “In general, Forum members view China’s increased actions in the region as a positive development, one that offers greater options for financing and development opportunities — both directly in partnership with China, and indirectly through the increased competition in our region.”

The most recent PIF meeting concluded with the island nations declaring a climate emergency and making it clear that climate action would be the most preferred front for engagement with all powers including China, US and Australia. Although the western powers, especially Australia had previously pledged to take climate action, the Pacific Island nations had expressed disappointment that the targets for phasing out of carbon emissions had not been met. Thus, greater realignment towards taking definitive climate action would be the next step in relations with the Pacific Islands. As Fiji’s Bainimarama put it, “Geopolitical point-scoring means less than little to anyone whose community is slipping beneath the rising seas. With jobs being lost to the pandemic, and families being impacted by the rapid rise in the price of commodities, their greatest concern isn’t geopolitics — it’s climate change.”

It is vital that the Pacific Island Countries band together to maintain solidarity, leverage the opportunities afforded to them due to competition brought about by China’s increased interest in the region and show solidarity in light of the unifying, clarifying priority for all Pacific leaders, which is survival.

The effects of climate change are already manifesting in “countries like Vanuatu, Fiji, Solomon Islands, Tonga which are no longer facing category five (severe tropical) cyclones once every 10 years, it’s once every two or three years.” Rising sea levels have allowed salt water to rise through the ground in countries like the Marshall Islands and Tuvalu, which pollute the existing fresh water sources. As former Kiribati President Anote Tong explains in an interview to The Drum, “climate change is not some hypothetical future threat – his islands may not be habitable by 2060.” Thus, it is vital that the Pacific Island Countries band together to maintain solidarity, leverage the opportunities afforded to them due to competition brought about by China’s increased interest in the region and show solidarity in light of the unifying, clarifying priority for all Pacific leaders, which is survival.

REFERENCES :

- Dirk H. R. Spennemann (1992) The politics of heritage: Second world war remains on central Pacific Islands, The Pacific Review, 5:3, 278-290, DOI: 10.1080/09512749208718990

- “China’s Position Paper on Mutual Respect and Common Development with Pacific Island Countries.” China’s Position Paper on Mutual Respect and Common Development with Pacific Island Countries, www.fmprc.gov.cn, 30 May 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202205/t20220531_10694923.html.

- Panuelo, D. (2022). DocumentCloud. Retrieved 1 August 2022, from https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/22037013-letter-from-h-e-david-w-panuelo-to-pacific-island-leaders-may-20-2022-signed

- The United States Government. (2022, May 31). United States – Aotearoa new zealand joint statement. The White House. Retrieved August 1, 2022, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/05/31/united-states-aotearoa-new-zealand-joint-statement/