The old world order is not returning; the international system is structurally transforming into a fragmented multipolar reality. In this age of disorder, flexible institutions and reformist leadership—exemplified by India—are essential to sustain global governance.

The 56th World Economic Forum Annual Meeting took place in Davos-Klosters, Switzerland, from January 19 to 23, 2026, under the theme “A Spirit of Dialogue.” The forum brought together global political, business, and intellectual leaders at a moment when the international order is not merely under strain but undergoing a deeper structural transformation. Discussions at Davos underscored a shared recognition that dialogue in today’s fractured global environment is not a sentimental ideal but a strategic necessity—particularly amid intensifying geopolitical competition, accelerating technological disruption, economic fragmentation, and the growing limitations of established institutional frameworks. Significantly, the conversations reflected a broader shift in global thinking, moving away from nostalgia for a stable post–Cold War order toward an urgent search for more flexible and adaptive forms of global governance capable of managing uncertainty, fragmentation, and persistent conflict.

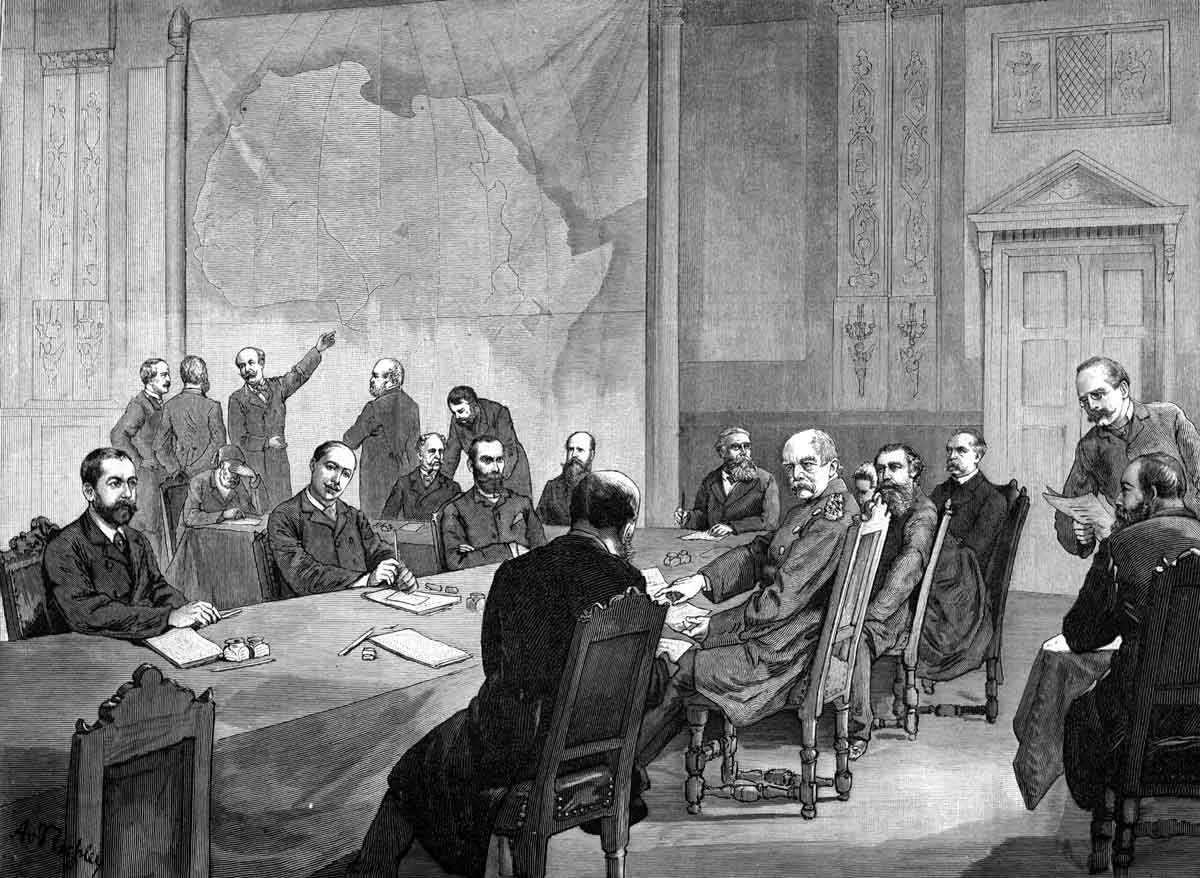

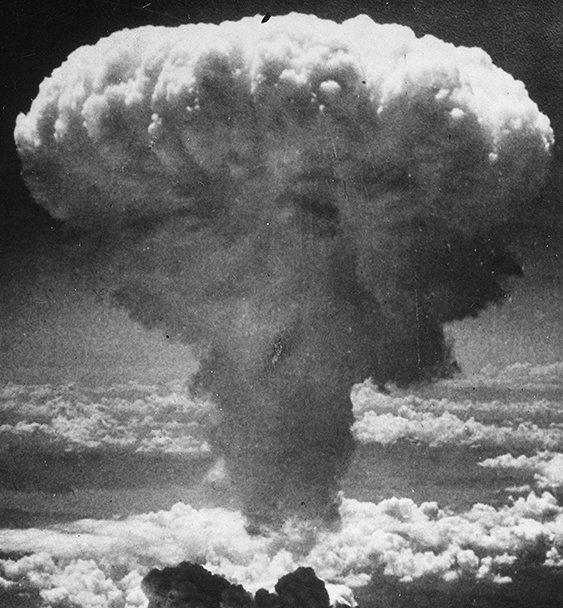

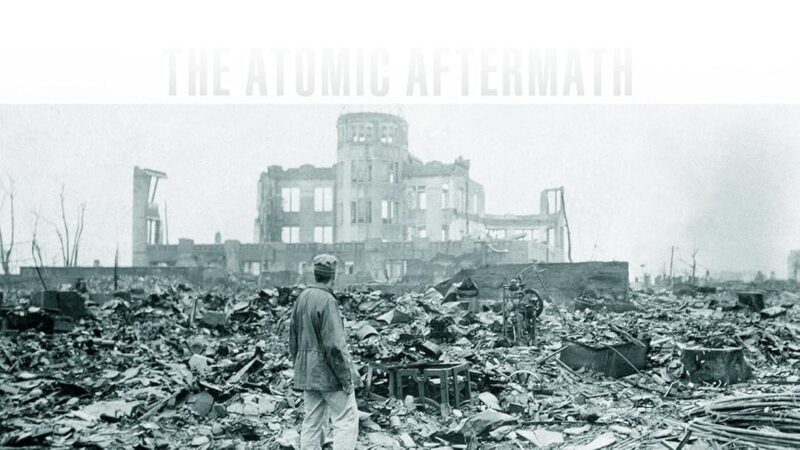

The contemporary international system is undergoing an unprecedented degree of geopolitical turbulence. Institutions such as the United Nations and other global governance mechanisms—established in the aftermath of the Second World War—were designed to manage conflict and promote cooperation within the structural realities of that era. Today, however, the assumptions underpinning these institutions no longer align with prevailing geopolitical conditions, rendering many of them increasingly ineffective and disconnected from contemporary realities. This growing institutional disconnect is inseparable from deeper structural changes in the global system itself. As Zack Cooper, a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, notes in his Stimson Center essay “An American Strategy for a Multipolar World”, “a multipolar world is now unavoidable, with legacy powers increasingly accompanied by a number of rising powers… this is a much more complex system than the multipolar dynamic that existed in Europe after the Congress of Vienna… today’s multipolar system is highly fragmented along regional and functional lines.” This observation captures the core challenge of the present international system: it is not merely shifting in power distribution, but fundamentally transforming in structure and complexity.

From Bipolarity to Fragmentation

The post–Second World War order was shaped initially by Cold War bipolarity and later by a brief unipolar moment following the end of the Cold War. In contrast, the current system is marked by fragmentation, instability, and a gradual transition toward multipolarity. Historically, periods of power transition—particularly multipolar configurations—have been associated with heightened uncertainty, miscalculation, and conflict. The present environment reflects this pattern, as competing power centres and overlapping crises push the international system toward persistent volatility.

In this volatile context, states are increasingly adopting hedging strategies to manage risks and vulnerabilities. From Europe to Asia and beyond, countries are diversifying partnerships, avoiding rigid alignments, and seeking strategic flexibility. This behaviour is neither anomalous nor irrational; rather, it is a structural response to systemic uncertainty. Such adaptive behaviour, however, is itself a symptom of deeper structural instability in the international system.

As many scholars, most notably Kenneth Waltz, have long argued, an emerging multipolar order tends to be among the most unstable configurations in international politics, marked by heightened risks of conflict, miscalculation, and escalation. With multiple powers competing simultaneously and no clear hegemon capable of stabilising the system, the international order becomes increasingly fragile and prone to error. The contemporary system appears to be operating on this edge, shaped by overlapping crises and rival power centres.

Compounding this instability is the rapid emergence of critical and disruptive technologies, advanced weapons platforms, cyber capabilities, and artificial intelligence. These developments further intensify volatility by lowering barriers to conflict, accelerating escalation dynamics, and complicating traditional deterrence frameworks. International experts at a 2025 conference warned that such technologies are “eroding present deterrence frameworks” and could destabilise the global security order without a global regulatory consensus. Similarly, the World Economic Forum’s Global Cybersecurity Outlook 2025 notes that “cybersecurity is entering an era of unprecedented complexity,” as the rapid adoption of AI without adequate safeguards creates far-reaching security risks requiring multilateral cooperation.

While some observers attribute current turbulence primarily to political leaders such as Donald Trump, this interpretation is overly simplistic. Trump’s policies may have accelerated existing trends, but they are not the root cause. The deeper drivers lie in structural shifts within the international system and in long-term transformations within American domestic politics that have altered the foundations of US global engagement.

Davos and the Recognition of a New World Order

These concerns have been openly acknowledged by global leaders at the World Economic Forum. Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, speaking at Davos, argued that “the old world order is not coming back,” cautioning against nostalgia-driven policymaking and warning that the global system is undergoing a rupture rather than a smooth transition. He further observed that economic interdependence has increasingly been weaponised and warned middle powers that “if you are not at the table, you are on the menu.” Such remarks reflect a growing recognition that disorder, competition, and power asymmetries are now embedded features of the international system.

Similarly, World Economic Forum President Børge Brende highlighted the depth of uncertainty confronting the global order, noting that “the political, geopolitical, and macroeconomic landscape is shifting under our feet.” Emphasising the limits of unilateralism and rigid frameworks, Brende stressed that “dialogue is a necessity, not a luxury,” reinforcing the idea that cooperation must persist even in an era of fragmentation. These statements underline a critical point: the challenge today is not the absence of institutions, but their inability to adapt to changing geopolitical realities.

French President Emmanuel Macron further reinforced this diagnosis at Davos by warning of a “shift towards a world without rules, where international law is trampled underfoot and where the law of the strongest prevails.” His remarks underscore the erosion of the post–Second World War multilateral framework under the pressure of returning imperial ambitions, coercive diplomacy, and unilateral action. Macron’s warning reflects a broader concern that global politics is increasingly shaped by power rather than norms. At the same time, he rejected intimidation as an organising principle of international relations, stating that “we prefer respect to bullies,” and called for effective multilateralism—one that is reformed and updated rather than dismantled.

Reforming Global Governance for an Age of Disorder

Against this backdrop, the central question is how states can navigate such geopolitical turbulence. A rigid, blueprint-based institutional approach—reminiscent of Cold War–era frameworks—is no longer viable. What is required instead are flexible, adaptive institutions capable of absorbing shocks, accommodating diverse interests, and operating under conditions of persistent uncertainty. Since traditional multilateralism is increasingly strained, it is essential to recognise that disorder itself is likely to remain a defining feature of the contemporary international system.

Any effort to design or reform institutions must therefore begin with this recognition. Fragmentation and regionalisation—particularly through minilateral and issue-based coalitions—are inevitable outcomes of a multipolar environment. However, this does not eliminate the need for global cooperation. Rather, it demands cooperation frameworks that are flexible, inclusive, and responsive to evolving geopolitical realities. Institutions must be capable of adapting to shifting power balances rather than attempting to impose outdated structures on a transformed system. In these tough times, the world requires greater cooperation and coordinated action, because the challenges we face—such as climate change, cyber threats, economic instability, and regional conflicts—are global in nature and cannot be solved through isolated national approaches.

Another limitation in current thinking is the tendency to interpret global politics solely through the lens of US–China rivalry. While great power competition undeniably shapes the international environment, such a narrow focus underestimates the agency of middle and regional powers. Many states actively shape outcomes, norms, and institutions rather than merely reacting to great power pressures. Effective institutional design must therefore reflect this distributed agency and avoid reducing global politics to a binary rivalry.

Equally important is the need to move beyond linear and deterministic thinking. The contemporary world is characterised by non-linear dynamics, uncertainty, and complex interactions. Predicting the future exclusively through the lens of past patterns—particularly those rooted in liberal or Cold War assumptions—is increasingly misleading. Institutional responses must be grounded in realism, flexibility, and adaptability rather than static or idealised models of order.

Recent initiatives such as Donald Trump’s proposal for a “Board of Peace,” driven largely by personal leadership and transactional logic, illustrate the limitations of personality-centric approaches to global governance. Given their temporary nature and the likelihood of reversal under future administrations, such initiatives lack durability. Moreover, such proposals are often unrepresentative and do not reflect the realities of the international system; they are based on authoritarian-style solutions rather than broad-based legitimacy, consensus, and institutional resilience. In contrast, reforming existing institutions—particularly the United Nations—offers a more sustainable path forward. Reforms that reflect contemporary geopolitical realities would enhance the UN’s relevance without undermining its foundational principles.

India’s Reformist Approach to Global Governance

India’s approach to global governance is particularly instructive in this context. When India criticises the United Nations or other global institutions, its objective is not to dismantle them but to reform them. This distinguishes India from countries such as China and Russia, which often seek to replace existing structures with alternative, and frequently anti-Western, institutional arrangements. India positions itself not as an anti-Western power, but as a non-Western one—committed to liberal democracy, pluralism, and engagement with existing global frameworks. As India’s Ministry of External Affairs has emphasised, “the architecture of global governance in 2025 for the future cannot be written in ink from 1945,” highlighting the need to update institutions rather than replace them.

This distinction is crucial. India has significantly benefited from the existing international order, and its economic transformation since the post-1991 reforms has been largely enabled by the stability, access to global markets, and investment flows that the post-World War II system provided. Consequently, India has little incentive to support a China-centric alternative. Reforming the current system, rather than replacing it, aligns with India’s long-term strategic interests. Moreover, India’s leadership and participation in forums such as the SCO and BRICS have played a stabilising role. Without India’s presence, these platforms could easily evolve into explicitly anti-Western blocs. India’s foreign policy is best understood as reformist rather than revisionist, acting as a bridge between the West and the Global South; as Chatham House notes, India seeks to “change the international order from within rather than overthrow it.” Yet many Western policymakers fail to understand India’s global vision and often categorise it alongside other revisionist powers, viewing India narrowly through a bilateral prism or primarily as a counterweight to China. This misreading overlooks India’s broader role as an independent norm-shaping power.

In light of these dynamics, the most effective strategy for navigating contemporary geopolitical turbulence lies in reforming and revitalising existing institutions rather than constructing entirely new ones based on rigid, blueprint-style thinking. A blueprint approach assumes that we can predict the future and design institutions accordingly—an assumption that is inherently flawed because the future is always uncertain and unknowable. Institutions must therefore be designed to capture the reality of moving from the known to the unknown and to adapt continuously as new challenges emerge. They must be made flexible, resilient, and responsive to disorder rather than designed to eliminate it. Accepting instability as a structural condition—and designing mechanisms of cooperation accordingly—offers the best chance of sustaining global governance in an increasingly fragmented world.

Feature Image Credit: www.byarcadia.org

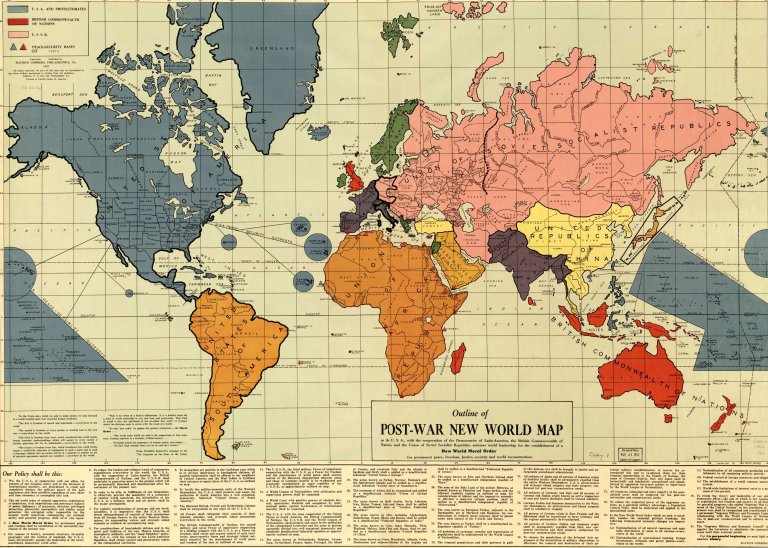

The post-World War II world map, drawn by Maurice Gomberg in 1941. The United States extends from Canada to the Panama Canal and includes Greenland.

The post-World War II world map, drawn by Maurice Gomberg in 1941. The United States extends from Canada to the Panama Canal and includes Greenland.