On 23 September 2024, Reuters published a news item quoting unnamed sources that said that India had ‘ invited political and military opponents of Myanmar’s ruling junta to attend a seminar in New Delhi. Even as the lack of corroboration of such a report puts it in the realm of conjecture, it is worthwhile mulling over the motivations or otherwise for such a seminal event to be even contemplated, especially in the light of implications for India’s Act East Policy.

TPF Occasional Paper: 10/2024

Recalibrating India’s Act East Policy: New Realities in Myanmar and Bangladesh

Maj Gen Alok Deb (Retd)

On 23 September 2024, Reuters published a news item quoting unnamed sources that said that India had ‘ invited political and military opponents of Myanmar’s ruling junta to attend a seminar in New Delhi’[i]. The item went on to specify that the shadow National Unity Government (NUG) and ethnic minority rebels from the states of Chin, Rakhine and Kachin bordering India had been invited to a seminar in mid-November, to be hosted by the Delhi-based Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA), a foreign policy think tank funded by the Government of India. The piece was also carried by some major Indian newspapers with its origin attributed to Reuters. At the time of writing, there has been no acknowledgement or rebuttal of this report by any government agency. Neither has the ICWA posted this on its website as a forthcoming event. Even as the lack of corroboration of such a report puts it in the realm of conjecture, it is worthwhile mulling over the motivations or otherwise for such a seminal event to be even contemplated, especially in the light of implications for India’s Act East Policy.

A Summary of India’s Act East Policy

India’s ‘Act East’ policy of 2014 is an initiative that takes off from its earlier ‘Look East’ policy. ‘Act East’ envisages initiatives at multiple levels with the nations of ASEAN and the wider Indo-Pacific region. These initiatives are to be taken forward through a process of continuous engagement at bilateral, regional and multilateral levels, thereby providing enhanced connectivity in its broadest sense, including political, economic, cultural and people-to-people relations.[ii]

To successfully implement the ‘Act East’ policy, the Indian government is working to make the North East its strategic gateway to ASEAN. Accordingly, it has increased the allocation for the region’s development by more than four times over the last 10 years.[iii] The North East is also poised to benefit from initiatives from countries like Japan which earlier this year had proposed developing an industrial hub in Bangladesh with supply chains to the North East, Nepal and Bhutan.[iv]

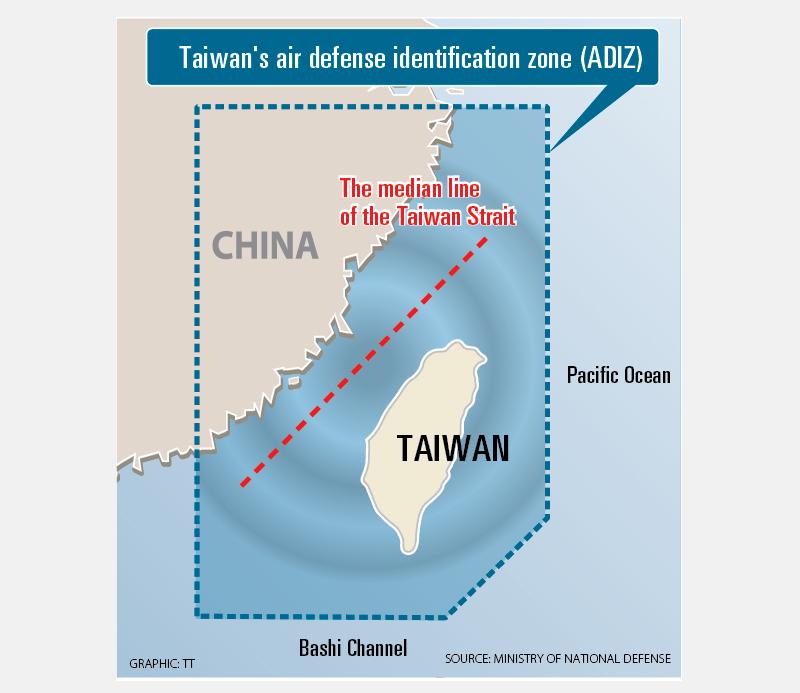

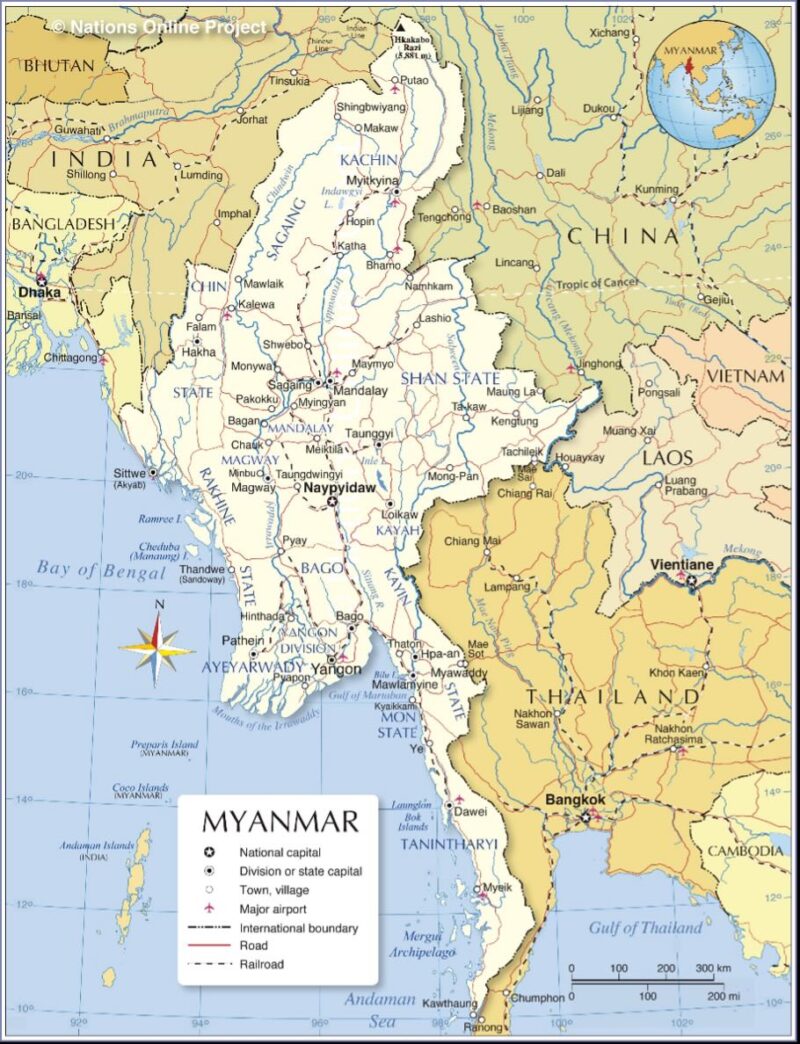

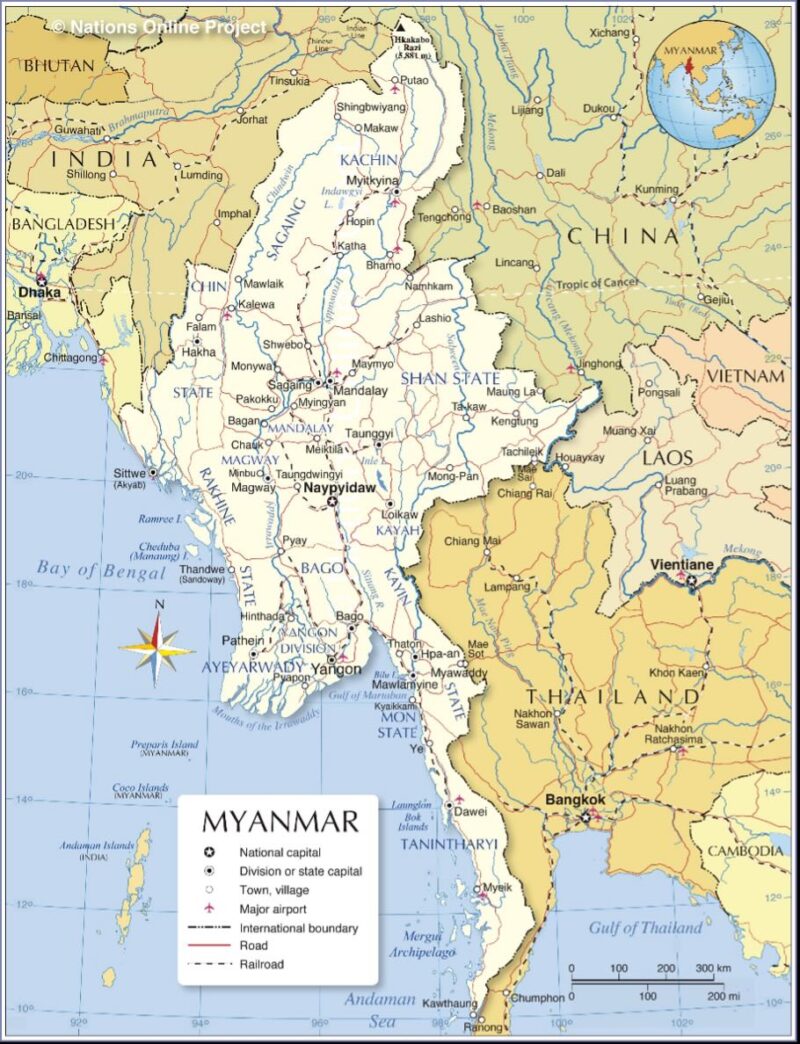

As the North East becomes India’s gateway to ASEAN, the centrality of Myanmar to our Act East becomes apparent. It is the key link in the road connectivity between India’s North East and other ASEAN nations whereby the free flow of inland goods, services and other initiatives to and from these nations to India can be ensured. The success or otherwise of Act East is thus directly affected by the security environment in Myanmar. Instability here will negatively impact our North Eastern states sharing borders with that country. The internal situation in Myanmar therefore becomes an area of prime concern for India, warranting close attention.

For similar reasons, another neighbour, Bangladesh, is equally important for the success of India’s Act East Policy. India’s North East has benefitted from good ties with Bangladesh, both security-wise and economically. Militancy in the North East has reduced over the last decade and a half. With Bangladesh agreeing to provide access to its ports in the Bay of Bengal for the movement of Indian goods, the North Eastern states have a shorter route to the sea. Additionally, states bordering Bangladesh such as Assam and Meghalaya have developed trade links with that country for mutual benefit. The BBIN (Bangladesh Bhutan India Nepal) Motor Vehicle Agreement for the Regulation of Passenger, Personal and Cargo Vehicular Traffic was signed in 2015 to ‘ promote safe, economically efficient and environmentally sound road transport in the sub-region and … further help each country in creating an institutional mechanism for regional integration’ is another mechanism for implementing our Act East and Neighbourhood First policies[v]. The role of Bangladesh here is pivotal.

State of the Civil War in Myanmar

Fighting in Myanmar is now in its fourth year. The military junta continues to suffer reverses on the battlefield. Large portions of Rakhine State and certain portions of Chin State are now under the control of the Arakan Army (AA). International Crisis Group has recently averred that ‘..in just a few months, the Arakan Army has created the largest area in Myanmar under the control of a non-state armed group – in terms of both size and population – and is now on the verge of securing almost all of Rakhine’[vi].

In Shan state to the North, the Three Brotherhood Alliance (TBA) of three Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs) had by December 2023, captured over 20,000 square kilometres of territory, including key border crossings and trade routes between China and Myanmar in Operation 1027[vii]. On 07 March 2024, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) launched Operation 0307 and successfully captured certain military posts across Kachin State close to the Chinese border. This forced the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military) to redeploy, further thinning out forces[viii]. Fighting also continues in other states and regions across the country, notably Sagaing and Kayah.

Associated Press deduces that ‘.. the announcement of the measure on state television amounts to a major, though tacit, admission that the army is struggling to contain the nationwide armed resistance against its rule..’.The Junta has since conscripted Rohingya youth and deployed them against the Rakhines.

Notwithstanding these losses, there is no let-up in the Tatmadaw’s efforts to combat the rebels. The Junta has resorted to conscription to stem rising attrition, activating an old law in this regard. Associated Press deduces that ‘.. the announcement of the measure on state television amounts to a major, though tacit, admission that the army is struggling to contain the nationwide armed resistance against its rule..’ [ix] To further contextualise, the same article stated the rebel National Unity Government’s (NUG) claim that more than 14,000 troops have defected from the military since the 2021 seizure of power. The Junta has since conscripted Rohingya youth and deployed them against the Rakhines. The Chins fear that they too will be acted upon similarly.[x]

To overcome the asymmetry of force especially in artillery and airpower, the rebels have acquired large numbers of drones. These are being used to bomb military positions, contributing significantly towards the successes of the CNA’s operations[xi]. To summarise, Myanmar’s civil war continues to see-saw with no signs of ebbing. The Junta continues to make periodic peace overtures to the NUG with conditionalities that the latter is unwilling to accept[xii]. With the multiplicity of actors and issues involved, there are no clear indications of how and when the conflict will be resolved.

Impact of the Myanmar Conflict on India’s North-East

The impact of Myanmar’s internal situation on India’s border states has progressively worsened. Initially, after the Junta takeover, it was Mizoram which bore the brunt. The state government citing common ethnicity and humanitarian concerns accepted the influx of Chins from Myanmar as a moral responsibility and initiated rehabilitation measures. These refugees along with earlier refugees from Bangladesh recently joined Kukis from Manipur, number around 44000 and continue to remain in refugee camps.[xiii] The Central government has had to reconcile its policy of preventing infiltration across borders with the societal realities of Mizoram. A positive outcome of this approach is that there has been no violence in Mizoram.

In Manipur, by September 2024, the 18-month-long ethnic conflict had resulted in over 225 deaths and some 60,000 people displaced.[xiv] The administration has been derided by both sides, more so with recent warnings about impending threats to law and order[xv] followed by retractions[xvi]. People of either community have been uprooted from their homes and moved to safe areas separated by buffer zones guarded by security forces. So great is the mutual suspicion that on the clamour of the Meiteis to replace the Assam Rifles, two battalions of this central force have been withdrawn and replaced by the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), against the wishes of the Kukis[xvii].

Voices for an independent ‘Kukiland’ for the Kuki Zo peoples are being raised,[xviii] which are variously interpreted as a demand for greater autonomy within Manipur or for a separate union territory. The current happenings also dredge up the old ghost of ‘Zale’n-gam’ or Kuki nation, comprising the Chin Kuki Zomi peoples (including Mizos) residing across India, Bangladesh and Myanmar. Zale’n- gam has few takers and appears restricted to a YouTube channel[xix]. Today both sides fight each other with a variety of weapons including improvised rockets and drones. Hostage-taking is the latest tactic that has been adopted.[xx]

Tension between the Nagas of Manipur and other communities is discernible with some reports of violence against the former.[xxi] As of now Nagas have kept out of the Kuki-Meitei dispute; also, other than the insurgent National Socialist Council of Nagaland ( Isak Muviah) faction (NSCN-IM) that is observing a ceasefire with the Centre, no other party has demanded integration of all Naga inhabited areas in India ( Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur) and Myanmar – the idea of Greater Nagalim.

At the state level, the responses of Mizoram and Manipur to the Myanmar crisis vary. This can be best seen in their reactions to the Centre’s recent notification to fence the entire 1643 Km Myanmar border and its earlier decision to end the Free Movement Regime that permits movement on both sides of the border for up to a distance of 16 km.[xxii] While the Mizoram government and tribes living in both states oppose the decisions, the Manipur government clamours for its implementation. Currently, only around 30 Km of the border has been fenced.

Since the Tatmadaw now has limited control over its border areas, it has become imperative for India to commence a structured dialogue with other warring parties in Myanmar’s border regions. This, with a view to restoring the situation in Manipur (and on the border) through mutually acceptable solutions at least for the short to medium term, is necessary. Only then can a modicum of security on the border be guaranteed. This involves navigating a maze of ethnic, religious, historical and societal issues with great sensitivity. The importance of such a dialogue cannot be overemphasised, more so because of recent developments in Bangladesh.

The Impact of Bangladesh’s ‘Second Liberation’

The events of 5 August 2024 that witnessed the overthrow of Sheikh Hasina’s government have proved to be yet another watershed in India-Bangladesh relations. India has invested more in the India-Bangladesh relationship than with any other neighbour in South Asia. A glance at the website of our Ministry of External Affairs[xxiii], where details of various agreements and summaries from the last Prime Ministerial meeting in Delhi in June 2024 are provided, will suffice to show just how strong and all-encompassing this relationship has become.

Persons or organisations associated with the previous regime have either fled the country or been placed under arrest and assets confiscated. A few have been killed by mobs. Bank accounts of others have been frozen. Jamaat e Islami which collaborated with the Pakistan Army in 1971 has been resurrected. Extremists with proven murder charges against them have been freed from prison, as have political prisoners.

At the time of writing, it is two months since the interim government headed by Chief Advisor Mohammed Yunus assumed charge. The country continues to make efforts to reestablish the rule of law. All wings of the armed forces have been given magisterial powers[xxiv]. The functioning of the judiciary, higher civil services, local administration, police, security agencies, banking, economy, and higher education, is under review. Persons or organisations associated with the previous regime have either fled the country or been placed under arrest and assets confiscated. A few have been killed by mobs. Bank accounts of others have been frozen.[xxv] The Jamaat e Islami which collaborated with the Pakistan Army in 1971 has been resurrected. Extremists with proven murder charges against them have been freed from prison, as have political prisoners. Commissions have been set up to suggest reforms in the constitution, electoral system, police, judiciary, public administration and in tackling corruption. Elections do not seem to be on the horizon yet. The advisers ( as the ministers are currently known) are new faces, not well known in India.

While this paper does not attempt to be a study of India-Bangladesh relations, the polarised politics in that country coupled with a perception that the misdeeds of Sheikh Hasina’s government were conducted with impunity because of Indian backing, is sure to impact India’s portrayal here.

With the removal of Sheikh Hasina, the India-Bangladesh relationship is undergoing a major reset. Statements of certain public figures and sentiments of a section of the population in that country suggest that a different perspective on the evolution of Bangladesh as a nation from 1971 onwards is emerging. While this paper does not attempt to be a study of India-Bangladesh relations, the polarised politics in that country coupled with a perception that the misdeeds of Sheikh Hasina’s government were conducted with impunity because of Indian backing, is sure to impact India’s portrayal here. This will make it an arduous task for both countries to go back to the trusted, cooperative and mutually beneficial relationship that existed. As mentioned, the list of achievements for both countries is far too numerous – settlement of land and oceanic borders, road, rail and riverine connectivity (including use of ports), economy and business ( both government and private), education including educational scholarships, technology, disaster management, border management, maritime security, military to military cooperation, improved people to people contacts, culture and health. As per records, of the 16 lakh visas issued by India for Bangladesh nationals in 2023, 4.5 lakhs were for medical treatment alone[xxvi]. Economies are so embedded that everyday necessities like onions are exported regularly to Bangladesh ( approximately 6 to 7 lakh tonnes annually).

Even as the new regime provides assurances on the security of minorities and acknowledges India as an important neighbour, the enthusiasm with which it has interacted with official interlocutors from a host of nations worldwide especially China, Pakistan and the US is noteworthy and indicates where its newfound priorities might lie.

A parallel reality, however, is that negative perceptions about India have historically found space in sections of Bangladesh’s polity. These have received a huge fillip after the change of regime with even settled agreements prone to misunderstanding. A recent example pertains to a tripartite agreement dating back to the Hasina period whereby electricity is to be imported from Nepal via India to Bangladesh. The agreement was signed in Kathmandu in the first week of October 2024. Newspaper reports from Bangladesh indicate that there is palpable resentment over the condition that Indian transmission systems inside Indian territory be utilised for this purpose since it increases costs per unit of electricity in Bangladesh.[xxvii] Another issue currently bedevilling relations is the state of minorities in Bangladesh who have faced attacks on their homes, businesses and religious places with some loss of life, since the protests in July. India’s concerns in this regard have been conveyed at the highest level. Even as the new regime provides assurances on the security of minorities and acknowledges India as an important neighbour, the enthusiasm with which it has interacted with official interlocutors from a host of nations worldwide especially China, Pakistan and the US is noteworthy and indicates where its newfound priorities might lie.

Larger Implications for India

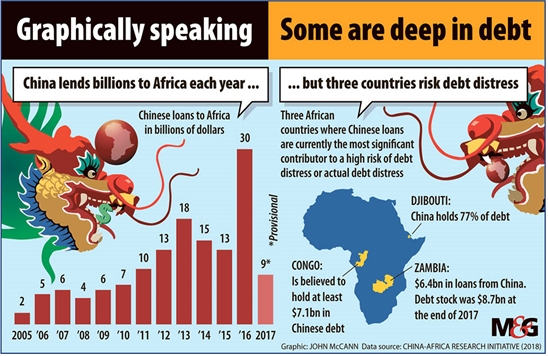

Bangladesh and Myanmar are pivotal for India’s Act East policy from the security, economic and connectivity angles. The issues pertaining to Myanmar and Manipur have been brought out earlier. A common concern affecting both nations and India is the Rohingya crisis. Despite international pressure and requests from Bangladesh for China to intercede with Myanmar on its behalf, there has been no positive response from Myanmar. Bangladesh, which currently hosts close to one million refugees,[xxviii] has publicly expressed its inability to accommodate any more Rohingyas and asked for a speedy ‘third country settlement’ [xxix]. A detailed report of the International Crisis Group (ICG) in October 2023[xxx]provides details of activities of militant organisations like the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO) and Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) which are involved in drug running from Myanmar along with Bangladeshi syndicates for sale of the product in that country. Their participation in violent crime and other illegal activity has become a pressing concern within Bangladesh. Rohingyas have infiltrated into India as well, and have been identified as far North as Jammu. The security implications of such migration for both Bangladesh and India are apparent. The insensitivity of the Myanmar Junta on this account is heightening security risks for India and Bangladesh and merits diplomatic intervention.

With the situation in Bangladesh evolving by the day, it is prudent for India to take a strategic pause as it weighs its options for pursuing its Act East policy. While giving the new regime in Bangladesh its due, India has to consider the impact of resurgent forces aided by inimical powers that aim to derail the India-Bangladesh relationship beyond repair. Even as both countries attempt to reestablish strong ties, the old adage preached by educated Bangladeshis in the context of support to Sheikh Hasina’s regime that ‘India should not put all its eggs in one basket’ resonates. While Myanmar geographically cannot provide the singular advantages that Bangladesh can, it is time for India to press for securing Myanmar’s cooperation to complete pending projects in that country, such as the Kaladan Multi-Modal Port Project (KMMPP) via Sittwe and Paletwa, that provides an alternate route to our North East, as well as the Trans Asian Highway (TAH) that provides connectivity with the rest of ASEAN, amongst others.

To summarise, two possible reasons for inviting rebel Myanmar groups to Delhi could be: first, the relative viability of either Bangladesh or Myanmar to help implement the Act East policy in light of the emerging situation in Bangladesh and the state of the civil war in Myanmar. The second, ensuring security on the India-Myanmar border, to prevent aggravating the situation in India’s border states.

Notes:

[i] ‘Exclusive: India extends unprecedented invite to Myanmar’s anti-junta forces, sources say’ Wa Lone and Devjyot Ghoshal Reuters September 23, 2024

[ii] ‘Govt aims to make Northeast gateway of ‘Act East Policy’: President Murmu’ Press Trust of India 27 June 2024.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] ‘Japan to tie landlocked Northeast India with Bangladesh’ Saleem Samad The Daily Messenger 05 March 2024.

[v] Press Information Bureau Government of India Ministry of Shipping note dated 10 June 2015

‘Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal (BBIN) Motor Vehicle Agreement for the Regulation of Passenger, Personal and Cargo Vehicular Traffic amongst BBIN’

[vi] ‘Breaking Away: The Battle for Myanmar’s Rakhine State Asia Report N°339 | 27 August 2024’ International Crisis Group (Executive Summary).

[vii] ‘As Myanmar’s Junta Loses Control in the North, China’s Influence Grows’ Jason Tower, United States Institute for Peace, August 1, 2024.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] ‘Facing setbacks against resistance forces, Myanmar’s military government activates conscription law ‘ Associated Press, February 12, 2024.

[x] ‘India’s ‘Forgotten Partition’ and the Myanmar Refugee Crisis’ Swapnarka Arnan The Diplomat 11 May 2024.

[xi] ‘We killed many … drones are our air force’: Myanmar’s rebels take on the junta from above. Aakash Hassan and Hannah Ellis-Petersen The Observer 20 January 2024.

[xii] ‘Armed Groups Snub Myanmar Junta ‘Peace’ Offer’ The Irrawaddy 28 September 2024

[xiii] ‘Centre provides 1,379 MT rice to Mizoram for Manipur, Myanmar, B’desh refugees’ Morung Express 25 September 2024.

[xiv] ‘Ethnic violence in India’s Manipur escalates, six killed’ Tora Agarwala Reuters September 7, 2024

[xv] ‘900 Kuki militants infiltrated Manipur from Myanmar, says Security Advisor’ India Today NE September 20 2024.

[xvi] ‘Input on infiltration by 900 Kuki militants could not be substantiated on the ground, says Manipur security advisor’ Vijaita Singh The Hindu 26 September 2024.

[xvii] ‘Kukis call removal of Assam Rifles from 2 Manipur areas ‘biased, appeasement’, Meiteis call it ‘victory’ Ananya Bhardwaj The Print 04 August 2024.

[xviii]‘ Manipur: Kuki-Zo organizations hold rallies, demand separate ‘Kukiland’ for peace by Northeast News

August 31, 2024.

[xix] YouTube channel titled ‘Zalengam Media’.

[xx] ‘Kuki militants seek release of ‘secessionist’ in Manipur’ Prawesh Lama and Thomas Ngangom Hindustan Times Sep 30, 2024.

[xxi] ‘Keep us out of your war, Manipur Naga body warns two warring communities’ The Hindu Bureau 06 February 2024

[xxii] ‘Government sanctions ₹31,000 crore to fence Myanmar border’ The Hindu

Published – September 18, 2024

[xxiii] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India website mea.gov.in.

[xxiv] ‘Navy, the air force also granted magistracy powers’ The Daily Star September 30 2024

[xxv] ‘Bank accounts of Joy Putul Bobby frozen’ Dhaka Tribune 30 Sep 2024.

[xxvi] ‘Indian High Commission in Dhaka, facing protests & threats, returns 20,000 visa applicants’ passports ‘ Ananya Bhardwaj The Print 29 September 2024.

[xxvii] ‘Bangladesh delegation in Nepal to sign the contract to import 40 MW electricity’ Dhaka Tribune 30 September 2024.

[xxviii] Operational Data Portal of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, for Bangladesh.

[xxix] ‘Bangladesh calls for faster resettlement process for Rohingya’ Ruma Paul Reuters September 8, 2024

[xxx] ‘Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh: Limiting the Damage of a Protracted Crisis’ International Crisis Group Autumn Update 04 October 20223.

Feature Image Credit: What does Sheikh Hasina’s resignation mean for India-Bangladesh relations? – aljazeera.com

Map Credit: National Online Project

Bangladesh Parliament Image: The Shattered Identity of a Nation: From Liberation to Chaos – borderlens.com

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Statue: Bangabandhu to Toppled Statue: Mujibur Rahman’s contested legacy post Bangladesh upheaval – Economic Times

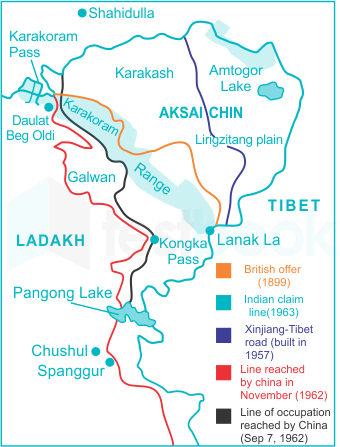

The opening skirmish of that conflict occurred in the North East with the capture, on 8th Sept, of the isolated Assam Rifles post at Dhola, on the southern slopes of the Thag La ridgeline. This post was surrounded and completely dominated by PLA positions on higher ground, and its loss was a foregone conclusion. The actual conflict commenced at approximately 0500 hours on 20th October, when the PLA launched a massive infantry attack, supported by artillery, on the 7 Infantry Brigade positions. The Brigade was deployed in a tactically unsound manner on direct orders of GOC 4 Corps, Lt Gen B M Kaul, along the Southern banks of the Namka Chu River over a 20 Km frontage instead of on the heights overlooking the river.

The opening skirmish of that conflict occurred in the North East with the capture, on 8th Sept, of the isolated Assam Rifles post at Dhola, on the southern slopes of the Thag La ridgeline. This post was surrounded and completely dominated by PLA positions on higher ground, and its loss was a foregone conclusion. The actual conflict commenced at approximately 0500 hours on 20th October, when the PLA launched a massive infantry attack, supported by artillery, on the 7 Infantry Brigade positions. The Brigade was deployed in a tactically unsound manner on direct orders of GOC 4 Corps, Lt Gen B M Kaul, along the Southern banks of the Namka Chu River over a 20 Km frontage instead of on the heights overlooking the river.