The profound legacies of the Mughal Empire, forged through a remarkable fusion of Persian and Sanskrit worlds, are now under siege from a mythical vision of India’s past.

On every 15 August since 1947, India’s Independence Day, the country’s prime minister unintentionally acknowledges the Mughals’ political legacy by delivering a nationwide address from the parapets of the mightiest symbol of Mughal power – Delhi’s massive Red Fort, built in 1648.

‘As is true of autocracies everywhere’, wrote David Remnick last April, ‘this Administration demands a mystical view of an imagined past.’ Although Remnick was referring to Trump’s America, something of the same sort could be said of India today. Informed by Hindutva (Hindu-centric) ideals, the country’s governing BJP party imagines a Hindu ‘golden age’ abruptly cut short when Muslim outsiders invaded and occupied an imagined sacred realm, opening a long and dreary ‘dark age’ of anti-Hindu violence and tyranny. In 2014, India’s prime minister declared that India had experienced 1,200 years of ‘slavery’ (ghulami), referring to ten centuries of Muslim rule and two of the British Raj. But whereas the British, in this view, had the good sense to go home, Muslims never left the land they had presumably violated and plundered. To say the least, India’s history has become a political minefield.

Today’s India would be unrecognisable without the imprint the Mughals had made, and continue to make, on its society and culture. It was they who, for the first time, unified most of South Asia politically.

Between the early 16th and the mid-18th century, towards the end of those 12 centuries of alleged ‘slavery’, most of South Asia was dominated by the Mughal Empire, a dazzling polity that, governed by a dynasty of Muslims, was for a while the world’s richest and most powerful state. Although it declined precipitously during the century before its liquidation by Queen Victoria in 1858, today’s India would be unrecognisable without the imprint the Mughals had made, and continue to make, on its society and culture. It was they who, for the first time, unified most of South Asia politically. On every 15 August since 1947, India’s Independence Day, the country’s prime minister unintentionally acknowledges the Mughals’ political legacy by delivering a nationwide address from the parapets of the mightiest symbol of Mughal power – Delhi’s massive Red Fort, built in 1648. Much of modern India’s administrative and legal infrastructure was inherited from Mughal practices and procedures. The basis of India’s currency system today, the rupee, was standardised by the Mughals. Indian dress, architecture, languages, art, and speech are all permeated by Mughal practices and sensibilities. It’s hard to imagine Indian music without the sitar, the tabla, or the sarod. Almost any Indian restaurant, whether in India or beyond, will have its tandoori chicken, kebab, biryani, or shahi paneer. One can hardly utter a sentence in a north Indian language without using words borrowed from Persian, the Mughals’ official language. India’s most popular entertainment medium – Bollywood cinema – is saturated with dialogue and songs delivered in Urdu, a language that, rooted in the vernacular tongue of the Mughal court, diffused throughout India thanks to its association with imperial patronage and the prestige of the dynasty’s principal capital, Delhi.

Yet, despite all this, and notwithstanding the prime minister’s national address at Delhi’s Red Fort, India’s government is engaged in a determined drive to erase the Mughals from public consciousness, to the extent possible. In recent years, it has severely curtailed or even abolished the teaching of Mughal history in all schools that follow the national curriculum. Coverage of the Mughals has been entirely eliminated in Class Seven (for students about 12 years old), a little of it appears in Class Eight, none at all in Classes Nine to 11, and a shortened version survives in Class 12. In 2017, a government tourism brochure omitted any mention of the Taj Mahal, the acme of Mughal architecture and one of the world’s most glorious treasures, completed in 1653. Lawyers in Agra, the monument’s site, have even petitioned the courts to have it declared a Hindu temple.

Although such radical measures have failed to gain traction, the national government has made more subtle efforts to dissociate the monument from the Mughals and identify it with Hindu sensibilities. For example, authorities have eliminated the initial ‘a’ from the name of one of its surrounding gardens, so that what had been Aram Bagh, the ‘Garden of Tranquility’, is now Ram Bagh, the ‘Garden of Ram’, the popular Hindu deity. This is the same deity to which India’s current government recently dedicated an extravagant temple complex on the site of the Babri Masjid, the mosque in eastern India that the Mughal Empire’s founder had built in 1528, but which a mob of Hindu activists tore down brick by brick in 1992.

All of this prompts two related questions: how did a rich, Persian-inflected Mughal culture sink such deep roots in today’s India in the first place? And why in recent years has the memory of that culture come under siege?

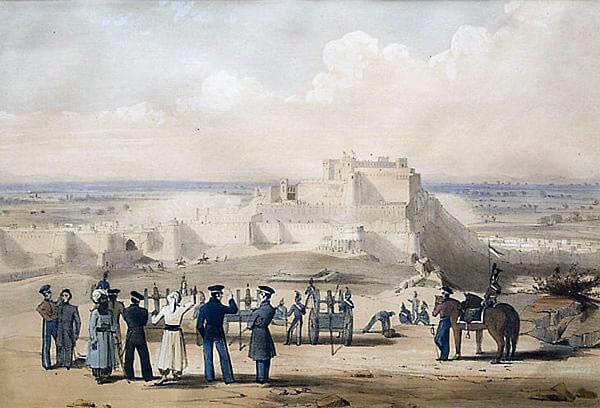

Ever since the early 13th century, a series of dynastic houses, known collectively as the Delhi sultanate, had dominated the north Indian plain. The last of these houses, the ethnically Afghan Lodis, was dislodged by one of the most vivid figures in early modern history, Zahir al-Din Babur(1483-1530). In 1526, Babur led an army of mostly free-born Turkish retainers from his base in Kabul, down through the Khyber Pass and onto the wide Indo-Gangetic plain, thereby launching what would become the Mughal Empire.

As was true for the Delhi sultans, the new polity’s success lay in controlling access to ancient trade routes connecting Delhi and Lahore with Kabul, Balkh, and Central Asian markets, such as Samarkand and Bukhara. For centuries, cotton and other Indian goods moved northwards along this route, while horses – more than a hundred thousand annually, by Babur’s day – moved southwards to markets across South Asia. War horses had long formed the basis of power for Indian states, together with native war elephants. But the larger and stronger horses preferred by Indian rulers had to be continually imported from abroad, especially from Central Asia’s vast, long-feathered grasslands where native herds roamed freely.

Having established a fledgling kingdom centred on Delhi, Agra and Lahore, Babur bequeathed to his descendants a durable connection to the cosmopolitan world of Timurid Central Asia, a refined aesthetic sensibility, a love of the natural world reflected in his delightful memoir, the Baburnama, and a passion for gardens. Aiming to recreate in India the refreshing paradisiac spaces that he knew from his Central Asian homeland, Babur built gardens across his realm, a practice his descendants would continue, culminating in the Taj Mahal.

Since he died only four years after reaching India, Babur’s new kingdom merely continued many institutions of the defeated Lodis, such as giving his most trusted retainers land assignments, from which they collected taxes and maintained specified numbers of cavalry for state use. It was Babur’s son Humayun (r. 1530-40, 1555-56) who took the first steps to deepen the roots of Mughal legitimacy in Indian soil, as when he married the daughter of an Indian Muslim landholder rather than a Central Asian Turk, a practice he encouraged his nobles to follow. More importantly, while seated in a raised pavilion (jharokha) that projected from his palace’s outer walls, he would greet the morning’s rising sun and show his face to the public, just as the sun showed itself to him. This followed an ancient practice of Indian rajas that subtly conflated the image of a seated monarch with the icon of a Brahmanical deity, before whom one pays respectful devotion through mutual eye contact (darshan).

The Mughals became further Indianised during the long reign of Humayun’s son Akbar (r. 1556-1605). Whereas for three centuries the Delhi sultans had struggled to defeat the Rajput warrior clans that dominated north India’s politics, Akbar adopted the opposite policy of absorbing them into his empire as subordinate kings. Nearly all Rajput kings accepted this arrangement, for by doing so they could retain rulership over their ancestral lands while simultaneously receiving high-ranking positions in Akbar’s newly created ruling class – the imperial mansabdars. Their new status also allowed them to operate on an all-India political stage instead of remaining provincial notables. Moreover, they were granted religious freedom, including the right to build and patronise Hindu temples. Over time, there emerged a warrior ethos common to both Mughals and Rajputs that superseded religious identities, allowing the latter to understand Muslim warriors as fellow Rajputs, and even to equate Akbar himself with the deity Rama. For their part, Akbar and his successors, as the Rajputs’ sovereign overlords, acquired regular tribute payments from subordinate dynastic houses, the service of north India’s finest cavalry, access to the sea through Rajasthani trade routes leading to Gujarat’s lucrative markets, and the incorporation of Rajput princesses in the imperial harem.

Moreover, since Rajput women could become legal wives of the emperor, from Akbar’s time onwards, an emperor’s child by a Rajput mother was eligible for the throne. As a result, Akbar’s son Jahangir (r. 1605-23) was half Rajput, as his mother was a Rajput princess. Jahangir, in turn, married seven daughters of Rajput rulers, one of whom was the mother of his imperial successor Shah Jahan, making the latter biologically three-quarters Rajput.

This last point proved especially consequential. As more Rajput states submitted to Mughal overlordship, the imperial court swelled into a huge, multi-ethnic and women-centred world in which the Rajput element steadily gained influence over other ethnicities. Moreover, since Rajput women could become legal wives of the emperor, from Akbar’s time onwards, an emperor’s child by a Rajput mother was eligible for the throne. As a result, Akbar’s son Jahangir (r. 1605-23) was half Rajput, as his mother was a Rajput princess. Jahangir, in turn, married seven daughters of Rajput rulers, one of whom was the mother of his imperial successor Shah Jahan, making the latter biologically three-quarters Rajput.

Inevitably, Rajput mothers in the imperial harem imparted their culture to their offspring, who were raised in the harem world. This allowed Indian sensibilities and values to seep deeply into Mughal imperial culture, reflected in imperial art, architecture, language, and cuisine. At the same time, the absorption of Rajput cavalry in the imperial system allowed native military practices to diffuse throughout the empire’s military culture.

The Mughals engaged with Sanskrit literary traditions and welcomed Brahmin and Jain scholars to their courts. From the 1580s on, Akbar sponsored Persian translations of the great Sanskrit epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, effectively accommodating Indian thought to Mughal notions of statecraft.

Like all authentically Indian emperors, moreover, the Mughals engaged with Sanskrit literary traditions and welcomed Brahmin and Jain scholars to their courts. From the 1580s on, Akbar sponsored Persian translations of the great Sanskrit epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, effectively accommodating Indian thought to Mughal notions of statecraft. Whereas the Sanskrit Mahabharata stressed cosmic and social order (dharma), its Persian translation stressed the proper virtues of the king. Similarly, the Sanskrit Ramayana was subtly refashioned into a meditation on Mughal sovereignty, while the epic’s hero, Rama, was associated with Akbar himself, as though the emperor were an avatar of Vishnu.

Beginning with Akbar, the Mughals also fostered cultural fusions in the domains of medicine and astronomy. By the mid-17th century, the Mughals’ Greco-Arab (Yunani) medical tradition had become thoroughly Indianised, as Indo-Persian scholars engaged with Indian (Ayurvedic) works on pharmacology and the use of native Indian plants.

Similarly, from the late 16th century on, Persian-Sanskrit dictionaries allowed Sanskrit scholars to absorb Arabo-Persian ideas that had derived from ancient Greek understandings of the uniformity of nature and laws of motion. That knowledge, together with astronomical tables patronised by Shah Jahan that enabled the prediction of planetary movements, then spread among the Mughal-Rajput ruling class at large.

The most telling indication of the public’s acceptance of the Mughals as authentically Indian is that in both the 18th and 19th centuries, when the empire faced existential threats from outside, native forces rallied around the Mughal emperor as the country’s sole legitimate sovereign. In 1739, the Persian warlord Nadir Shah invaded India, routed a much larger Mughal army, sacked Delhi, and marched back to Iran with enormous loot, including the symbolically charged Peacock Throne. At this moment, the Marathas, who for decades had fiercely resisted the imposition of Mughal hegemony over the Indian peninsula, realised that the Mughals represented the ultimate symbol of Indian sovereignty and must be preserved at all costs. The Marathas’ chief minister Baji Rao (1700-40) even proposed that all of north India’s political stakeholders form a confederation to support and defend the weakened Mughal dynasty from foreign invaders.

Similarly, by the mid-19th century, the English East India Company had acquired de facto control over much of the subcontinent, while the reigning Mughal ruler, Bahadur II (r. 1837-57), had been reduced to a virtual prisoner in Delhi’s Red Fort, an emperor in name only. But in 1857, a rebellion broke out when a disaffected detachment of the Company’s own Indian troops massacred their English officers in the north Indian cantonment of Meerut. Seeking support for what they hoped would become an India-wide rebellion, the mutineers then galloped down to Delhi and enthusiastically rallied around a rather bewildered Bahadur II. Notwithstanding his own and his empire’s decrepit condition, to the rebels, this feeble remnant of the house of Babur still represented India’s legitimate sovereign.

Through the Mughals’ twilight years, spanning the two incidents mentioned above, one emperor was especially revered in public memory – ‘Alamgir (r. 1658-1707), widely known today by his princely name, Aurangzeb. Upon his death, large and reverential crowds watched his coffin move 75 miles across the Deccan plateau to Khuldabad, a saintly cemetery in present-day Maharashtra. There, the emperor’s body was placed, at his own request, in a humble gravesite open to the sky, quite unlike the imposing monuments built to glorify the memory of his dynastic predecessors (excepting Babur). That simple tomb soon became an object of intense popular devotion. For years, crowds thronged his gravesite, beseeching ‘Alamgir’s intercession with the unseen world, for his saintly charisma (baraka) was believed to cling to his gravesite, just as in life it had clung to his person. For, during his lifetime, the emperor was popularly known as ‘Alamgir zinda-pir, or ‘Alamgir, the living saint’, one whose invisible powers could work magic.

‘Alamgir’s status as a saintly monarch continued to grow after his death in 1707. Already in 1709, Bhimsen Saksena, a former imperial official, praised ‘Alamgir for his pious character and his ability to mobilise supernatural power in the empire’s cause. In 1730, another retired noble, Ishwar Das Nagar, credited ‘Alamgir for the exceptional peace, security, and justice that had characterised his long reign. Nagar’s account followed a spate of histories that praised the emperor as a dedicated, even heroic administrator, and his half-century reign as a ‘golden age’ of governmental efficiency.

Further contributing to ‘Alamgir’s cult was the appearance of hundreds of images depicting the emperor engaged in administration, military activity, or religious devotion. Reflecting the extent of the ‘Alamgir cult, many of these post-1707 paintings were produced not at the imperial court but in north India’s Hindu courts, including those of the Mughals’ former enemies. No other Mughal emperor was so venerated, and for so long a period, as ‘Alamgir.

Over time, however, Indians gradually came to see the Mughal period – and especially ‘Alamgir’s reign – in an increasingly negative light. As the East India Company attained control over South Asia in the late 18th century, British administrators, being unable as foreigners to deploy a nativist rationale to justify their rule, cited the efficiency, justice, peace and stability that they had brought to their Indian colony. And because the Mughals had immediately preceded the advent of Company rule, those rulers were necessarily construed as having been inefficient and unjust despots in a war-torn and unstable land. The colonial understanding of Muslims and Hindus as homogeneous and mutually antagonistic communities also facilitated aligning colonial policies with the old Roman strategy of divide et impera. More perniciously, the colonial view of the Mughals as alien ‘Mahomedans’ who had oppressed a mainly non-Muslim population reinforced the notion of a native Hindu ‘self’ and a non-native Muslim ‘other’ – constructions that would bear bitter fruit.

Although originating from within the colonial regime, such ideas gradually percolated into the public domain as the 19th century progressed and Indians became increasingly absorbed in the Raj’s educational and administrative institutions. It was not until the 1880s, with the first stirrings of Indian nationalist sentiment, however, that such colonial tropes became widely politicised. As the possibility of an independent nation took root, Indian nationalists began to look to their own past for models that might inspire and mobilise mass support for their cause. The writing of history soon became a political endeavour, ultimately degenerating into a black-and-white morality play that clearly distinguished heroes from villains. In short, India’s precolonial past became a screen onto which many – though not all – Hindu nationalists projected the tropes of the Hindu self and the Muslim other.

Between 1912 and 1924, one of India’s most esteemed historians, Jadunath Sarkar, published his five-volume History of Aurangzib, the princely name of ‘Alamgir, who would soon become the most controversial – and ultimately the most hated – ruler of the Mughal dynasty. Sarkar’s study was so detailed, so thoroughly researched, and so authoritative that, in the century following its publication, no other historian even attempted a thorough survey of ‘Alamgir’s reign.

Importantly, Sarkar wrote against the backdrop of the Great War and a nationalist movement that was just then reaching a fever pitch. In 1905, Lord Curzon, the Viceroy for India, had partitioned Sarkar’s native province of Bengal in half, a cynical divide-and-rule measure that ‘awarded’ Bengali Muslims with their own Muslim-majority province of eastern Bengal. The very next year, there appeared the All-India Muslim League, a political party committed to protecting the interests of India’s Muslims. Meanwhile, the partition of Bengal had provoked a furious protest by Bengali Hindus, leading to India-wide boycotts against British-made goods. Ultimately, the government gave in to Hindu demands and, in 1911, annulled the partition, which only intensified fear and anxiety within India’s Muslim minority community.

It was in this highly charged political atmosphere that Sarkar worked on his biography of ‘Alamgir. With each successive volume of his study, the emperor was portrayed in darker colours, as were Muslims generally. In the end, Sarkar blamed ‘Alamgir for destroying Hindu schools and temples, thereby depriving Hindus of the ‘light of knowledge’ and the ‘consolations of religion’, and for exposing Hindus to ‘constant public humiliation and political disabilities’. Writing amid the gathering agitation for an independent Indian nation, Sarkar maintained that ‘no fusion between the two classes [Hindus and Muslims] was possible’, adding that while a Muslim might feel that he was in India, he could not feel of India, and that ‘Alamgir ‘deliberately undid the beginnings of a national and rational policy which Akbar [had] set on foot.’

Perhaps more than any other factor, Sarkar’s negative assessment of ‘Alamgir has shaped how millions have thought about that emperor’s place in Indian history. Since the publication of History of Aurangzib, professional historians have generally shied away from writing about the emperor, as though he were politically radioactive. This, in turn, opened up space in India’s popular culture for demagogues to demonise the Mughal emperor. For millions today, ‘Alamgir is the principal villain in a rogues’ gallery of premodern Indo-Muslim rulers, a bigoted fanatic who allegedly ruined the communal harmony established by Akbar and set India on a headlong course that, many believe, in 1947, culminated in the creation of a separate Muslim state, Pakistan. In today’s vast, anything-goes blogosphere, in social media posts, and in movie theatres, he has been reduced to a cardboard cutout, a grotesque caricature serving as a historical punching bag. A recent example is the film Chhaava, a Bollywood blockbuster that was released on February 14, 2025 and has since rocketed to superstar status. Among films in only their sixth week since release, already by late March, it had grossed the second-largest earnings in Indian cinema history.

Loosely based on a Marathi novel of the same title, Chhaava purports to tell the story of a pivotal moment in ‘Alamgir’s 25-year campaign to conquer the undefeated states of the Deccan plateau. These included two venerable sultanates, Bijapur and Golkonda, and the newly formed Maratha kingdom, launched in 1674 by an intrepid chieftain and the Mughals’ arch-enemy, Shivaji (r. 1674-80). The film concerns the reign of Shivaji’s elder son and ruling successor, Sambhaji (r. 1680-89), his struggles with Mughal armies, and finally his capture, torture, and execution at ‘Alamgir’s order in 1689.

The film is not subtle. With its non-stop violence, gratuitous blood and gore, overwrought plot, and black-and-white worldview, the movie turns the contest between Sambhaji and ‘Alamgir into a cartoonish spectacle, like a Marvel Comics struggle between Spiderman and Doctor Doom. Whereas Sambhaji single-handedly vanquishes an entire Mughal army, ‘Alamgir is pure, menacing evil. Mughal armies display over-the-top brutality toward civilians: innocent Indians are hanged from trees, women are sexually assaulted, a shepherdess is burned to death, and so forth.

In reality, ‘Alamgir is not known to have plundered Indian villages or attacked civilians (unlike the Marathas themselves, whose raids in Bengal alone caused the deaths of some 400,000 civilians in the 1740s). On the other hand, contemporary sources record Sambhaji’s administrative mismanagement, his abandonment by leading Maratha officers inherited from his father reign, his weakness for alcohol and merry-making, and how, instead of resisting Mughal forces sent to capture him, he hid in a hole in his minister’s house, from which he was dragged by his long hair before being taken to ‘Alamgir.

Historical accuracy is not Chhaava’s strength, nor its purpose. More important are its consequences. Within weeks of its release, the film whipped up public fury against ‘Alamgir and the Mughals. In one venue where the movie was showing, a viewer wearing medieval warrior attire rode into the theatre on horseback; in another, a viewer became so frenzied during the film’s protracted scene of Sambhaji’s torture that he leapt to the stage and began tearing the screen apart.

Politicians swiftly joined the fray. In early March, a member of India’s ruling BJP party demanded that ‘Alamgir’s grave be removed from Maharashtra, the heartland of the Maratha kingdom. On 16 March, another party member went further, demanding that the emperor’s tomb be bulldozed. The next day, a riot broke out in Nagpur, headquarters for the far-right Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, India’s paramilitary Hindu supremacist organisation. It began when around 100 activists who supported bulldozing ‘Alamgir’s grave burned an effigy of the emperor. In response, a group of the city’s Muslims staged a counter-protest, culminating in violence, personal injuries, the destruction of property, and many arrests. The fevered demand for bulldozing ‘Alamgir’s final resting place, however, is deeply ironic. In 1707, Sambhaji’s son and eventual successor to the Maratha throne, Shahu, travelled 75 miles on foot to pay his pious respects to ‘Alamgir’s tomb.

In the end, the furore over ‘Alamgir’s gravesite illustrates the temptation to adjust the historical past to conform to present-day political priorities. Indicating the Indian government’s support for Chhaava’s version of history, in late March, India’s governing party scheduled a special screening of the film in New Delhi’s Parliament building for the prime minister, Cabinet ministers, and members of parliament.

Nor is it only the historical past that is being adjusted to accord with present-day imagination. So is territory. In 2015, the Indian government officially renamed New Delhi’s Aurangzeb Road – so-named when the British had established the city – after a former Indian president. Eight years later, the city of Aurangabad, which Prince Aurangzeb named for himself while governor of the Deccan in 1653, was renamed Sambhaji Nagar, honouring the man the emperor had executed in 1689.

Such measures align with the government’s broader agenda to scrub from Indian maps place names associated with the Mughals or Islam and replace them with names bearing Hindu associations, or simply to Sanskritise place-names containing Arabic or Persian lexical elements. Examples include: Mustafabad to Saraswati Nagar (2016), Allahabad to Prayagraj (2018), Hoshangabad to Narmadapuram (2021), Ahmednagar to Ahilyanagar (2023), and Karimgunj to Sribhumi (2024). Many more such changes have been proposed – at least 14 in the state of Uttar Pradesh alone – but not yet officially authorised.

It is said that the past is a foreign country. Truly, one can never fully enter the mindset of earlier generations. But if history is not carefully reconstructed using contemporary evidence and logical reasoning, and if it is not responsibly presented to the public, we risk forever living with a ‘mystical view of an imagined past’ with all its attendant dangers, as Remnick warns.

This essay was published earlier on www.engelsbergideas.com

Feature Image Credit: www.engelsbergideas.com

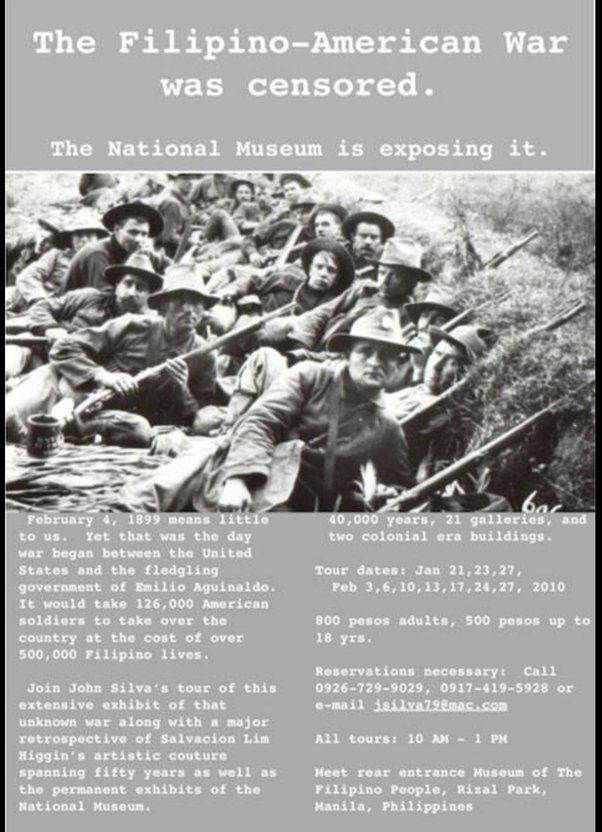

The Philippines, a twice-colonized archipelago that achieved its complete independence in 1946, is a member of the ASEAN and an essential player in the geopolitics of the Southeast Asia region. Its status is owed mainly to its rapidly growing economy, of which the services industry is the most significant contributor, comprising 61% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bajpai, 2022). Services refer to various products – for example, business outsourcing, tourism, and the export of skilled workers, healthcare workers, and labourers in other industries. In recent years, a growing demand for qualified professionals has grown as the economy has grown, thus necessitating more robust educational systems (Bajpai, 2022). Although the Philippines has a high literacy rate, hovering at around 97%, the efficacy of its educational system is often called into question (“Literacy Rate and Educational Attainment”, 2020). Administration oversight, infrastructural deficiencies, and pervasive corruption in the government that seeps into the entities responsible for educational reform are significant issues that legitimize these doubts (Palatino, 2023). However, reforming the current flaws in the system requires an understanding of the basic underlying structure of the country’s educational system as it is today. This fundamental understanding can help clarify specific political trends in the status quo and highlight the importance of proper historical education in developing a nation. Despite its ubiquity in nearly every curriculum, the study of history as a crucial part of the education system is often not prioritized, leading to an underdeveloped understanding of the society’s culture and previous struggles with colonial exploitation. Though it is present in the Philippines’ education today, it continues to change because of its historically dynamic demographic and political atmosphere.

The Philippines, a twice-colonized archipelago that achieved its complete independence in 1946, is a member of the ASEAN and an essential player in the geopolitics of the Southeast Asia region. Its status is owed mainly to its rapidly growing economy, of which the services industry is the most significant contributor, comprising 61% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bajpai, 2022). Services refer to various products – for example, business outsourcing, tourism, and the export of skilled workers, healthcare workers, and labourers in other industries. In recent years, a growing demand for qualified professionals has grown as the economy has grown, thus necessitating more robust educational systems (Bajpai, 2022). Although the Philippines has a high literacy rate, hovering at around 97%, the efficacy of its educational system is often called into question (“Literacy Rate and Educational Attainment”, 2020). Administration oversight, infrastructural deficiencies, and pervasive corruption in the government that seeps into the entities responsible for educational reform are significant issues that legitimize these doubts (Palatino, 2023). However, reforming the current flaws in the system requires an understanding of the basic underlying structure of the country’s educational system as it is today. This fundamental understanding can help clarify specific political trends in the status quo and highlight the importance of proper historical education in developing a nation. Despite its ubiquity in nearly every curriculum, the study of history as a crucial part of the education system is often not prioritized, leading to an underdeveloped understanding of the society’s culture and previous struggles with colonial exploitation. Though it is present in the Philippines’ education today, it continues to change because of its historically dynamic demographic and political atmosphere.

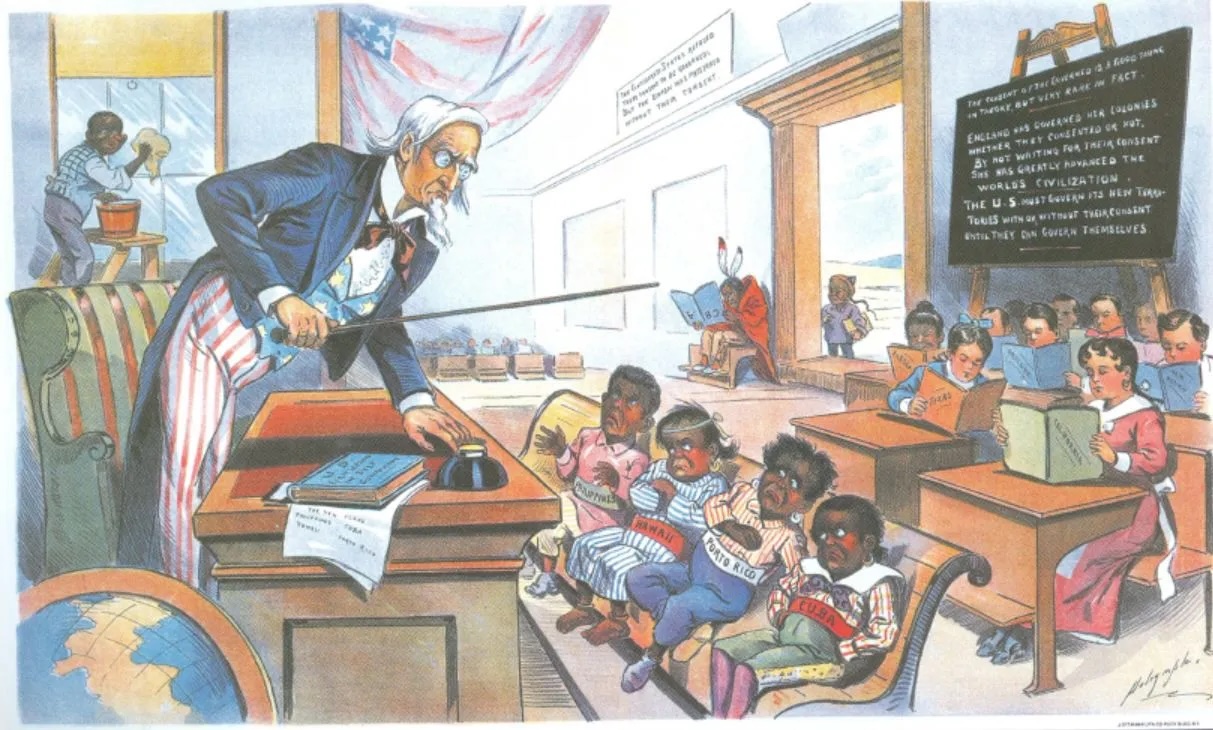

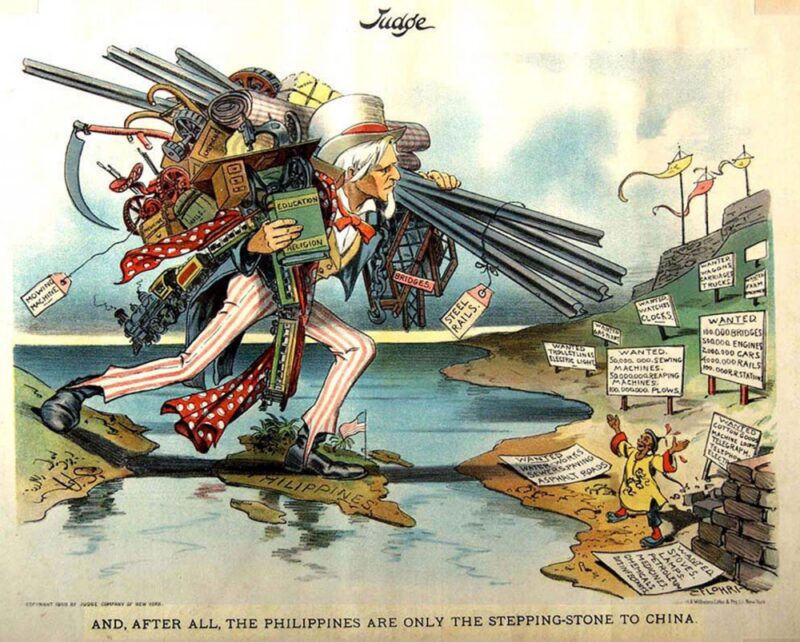

Uncle Sam, loaded with implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to get across the Pacific to China (represented by a small man with open arms), who excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. With the expansionist policy gaining greater traction, the possibility for more imperialistic missions (including to conflict-ridden China) seemed strong. The cartoon might be arguing that such endeavours are worthwhile, bringing education, technological, and other civilizing tools to a desperate people. On the other hand, it could be read as sarcastically commenting on America’s new propensity to “step” on others. “AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA,” in Judge Magazine, 1900 or 1902.

Uncle Sam, loaded with implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to get across the Pacific to China (represented by a small man with open arms), who excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. With the expansionist policy gaining greater traction, the possibility for more imperialistic missions (including to conflict-ridden China) seemed strong. The cartoon might be arguing that such endeavours are worthwhile, bringing education, technological, and other civilizing tools to a desperate people. On the other hand, it could be read as sarcastically commenting on America’s new propensity to “step” on others. “AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA,” in Judge Magazine, 1900 or 1902.