[powerkit_button size=”lg” style=”info” block=”false” url=”https://admin.thepeninsula.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/TPF-Research-Paper-Killing-in-War-1.pdf” target=”_blank” nofollow=”false”]

Download

[/powerkit_button]

Introduction:

How does it come about that humans kill each other en masse in wars? Within the animal kingdom, they seem to have a special position in this respect. Many animal species have a killing taboo within the species, but at the same time, there is a displacement competition, which is often decided by fights. This displacement of conspecifics corresponds to the formation of communities as well as processes of belonging to or exclusion from them. If the displaced conspecifics do not succeed in forming or joining their own communities, they usually perish, for example, because they are denied access to food sources. The displacement of conspecifics serves their own survival and the formation of a group that enables this survival directly or in the transmission of the biological heritage.

Living and surviving in the community, exclusion and displacement of conspecifics not belonging to the community – this can be considered as a basic pattern of conflicts within a species. In the animal kingdom, such conflicts are usually ritualized rank fights in which the killing of the opponent is usually avoided. However, this cannot hide the fact that killing also takes place here – for example, when the inferior is forced into a territory where he has no chance of survival (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1984). While in the animal kingdom the right of the physically stronger is almost unrestricted, there is a special feature in humans. Because of their intelligence, they are able to recognize that displacement from the community means immediate death and makes biological reproduction impossible (Orywal et al., 1995).

Recognition of the connection between displacement from the community (or displacement of one’s own by competing communities) and personal death or restriction of reproductive opportunity is the decisive reason for the skipping of the killing taboo within the human species.

Recognition of the connection between displacement from the community (or displacement of one’s own by competing communities) and personal death or restriction of reproductive opportunity is – according to my central hypothesis – the decisive reason for the skipping of the killing taboo within the human species. In addition, there is in the human being the ability, also developed by his mind, that the weakest or a group of weaker can kill the strongest. This happens with the help of tools, above all weapons, but also by “cunning and trickery”, i.e. by the use of intelligence. At the same time, this basic constellation also gives rise to the possible realization that a fight to the death can lead to the downfall of one’s own community. At a certain point in the conflict, it may therefore be more advisable to abandon the struggle and secure one’s own survival through other efforts – e.g., through improved food production, development of new technical processes, etc. (this is the core idea of Hegel’s struggle for recognition; Herberg-Rothe, 2007).

Defensive also appears in cases where the militant preservation of one’s identity is not a reaction to an attack from outside but means an attempt to prevent the internal disintegration of one’s community. When a community is threatened by internal tensions, war may serve to stabilize it by fighting an external enemy. Paradigmatic for this is the well-known dictum of Kaiser Wilhelm II at the beginning of World War I that he no longer knew any parties, he only knew Germans.

Likewise, wars are waged in order to establish a community with its own identity in the first place. Here, the war is supposed to constitute the political greatness through whose anticipated existence it legitimizes itself. This motif emerges most clearly in the national-revolutionary liberation movements, whose strategy is to establish in the struggle the nation for which the war is waged. The talk of the purifying power of war (Ernst Jünger) or the purifying function of violence (Frantz Fanon) acquires its political content here. In the struggle, the community is to be “forged together” (Münkler calls this the existential dimension of war; Münkler, 1992).

This keeps people in its clutches by no means exclusively because war is essentially determined by feelings (van Creveld, 1998 and Ehrenreich, 1997), but because it subjectively or objectively serves the material as well as ideal self-preservation of communities internally and externally. It is true that feelings play an essential, if not often even decisive role within wars – but the respective decision to go to war is in the rarest cases dominated by feelings alone. With this determination, however, only one side is mentioned. Defence and self-preservation appear as the real core of war only insofar as it is determined by the aspect of fighting. If, on the other hand, we take more account of its “original violence”, the first moment of Clausewitz’s “whimsical trinity”, and the membership of the combatants in a comprehensive community, war remains equally determined by the aspect of the violent “wanting to have more” (Plato) of material or ideal goods as by the preservation (or creation) of one’s own identity in the struggle, in the displacement competition of communities.

Let us recapitulate why this cut-throat competition is violent. In a non-violent competition between communities, one of them can be defeated. In order to preserve its physical or symbolic existence, the side that subjectively or objectively sees itself as the loser resorts to violent means. This is the fear of the physical or symbolic death of one’s own community, which can be maintained solely by struggle and, in the last resort, by war. Contrary to the assumption of Thomas Hobbes, the founder of modern political theory, according to my hypothesis, the fear of one’s own death does not lead to the abandonment of the struggle for life and death, but rather to its unleashing.

While Hobbes’s assumption may be largely plausible with respect to single individuals, although it underestimates the momentum of self-definition through violence (Sofsky, 1996), it is fundamentally wrong with respect to communities. Here, many individuals put their lives on the line precisely because they thereby enable the “survival of the community” and thus their own symbolic or biological survival. The same mechanism of displacement competition, however, can also lead to the insight that the preservation and strengthening of one’s own community can be promoted much better by cooperative behaviour than by a violent conflict.

If we apply this hypothesis to the interstate sphere, all those approaches fail that derive causes of war only from a single essence, for example from violent struggle (Hondrich, 2002), from the apparently aggressive nature of man or from the struggle for survival (sociobiological theories). The same is true, conversely, for attempts at explanation that see human beings as basically peaceable and seek the causes of wars solely in structures that have taken on an independent existence, such as the state, “capitalism,” the arms industry, dictatorships, or the lack of democratic participation.

Rather, violence and war are a possibility of self-preservation inherent in human action and, at the same time, of self-delimitation (“wanting more” of material as well as ideal things) of communities. Since this possibility can never be completely excluded, the decisive task of political action is the limitation of violence and war in world society.

Abolishing proximity and creating distance

In his study on killing, former Colonel Dave Grossman describes his experiences with U.S. Army training programs that teach soldiers how to kill. He sees the decisive approach in switching off the soldiers’ thinking and automating their actions. Using historical examples, Grossman tries to prove that in a battle only 15-25% of soldiers actually have the willingness to kill others. Grossman concludes that there is an anthropological inhibition to kill others “eye to eye” (Grossman, 1995). But 15-25 of those involved in war who kill, rape, maim are, in this perspective, either mentally ill to an even lesser degree or subject to a process of violence taking on a life of its own. Violence is perhaps the drug that is most quickly addictive and considered “normal” by its practitioners.

According to Grossman, there is an inhibition to killing due to the perceived anthropological sameness and the resulting proximity to the respective opponent, it is precisely this proximity that leads to explosive excesses of violence in mixed settlement areas.

While, according to Grossman, there is an inhibition to killing due to the perceived anthropological sameness and the resulting proximity to the respective opponent, it is precisely this proximity that leads to explosive excesses of violence in mixed settlement areas. The conclusions drawn from this are extremely contradictory. While in cases of great (spatial or interpersonal) distance the killing inhibition is eliminated by the fact that the opponent is no longer perceived in his sameness as a human being, the use of force in complex and confusing civil war situations can contribute to the creation of distance between people. Last, however, distance can also lead to the limitation of violence. Proximity and distance thus structure the occurrence of violence in very different ways.

Eliminating proximity between opponents to reduce the inhibition to kill can be done in very different ways. Systematically, three methods can be distinguished that have also played a major role historically: first, the creation of spatial distance, second, social distance, and third, the integration of the combatants into tightly knit communities in which it is no longer the individual who acts, but the group. Belonging to a group and its courses of action are then stronger than the individual’s inhibition to kill.

One instrument for creating social distance is the degradation of the opponent by denying him his humanity. The demonization of the opponent is the prerequisite for his destruction.

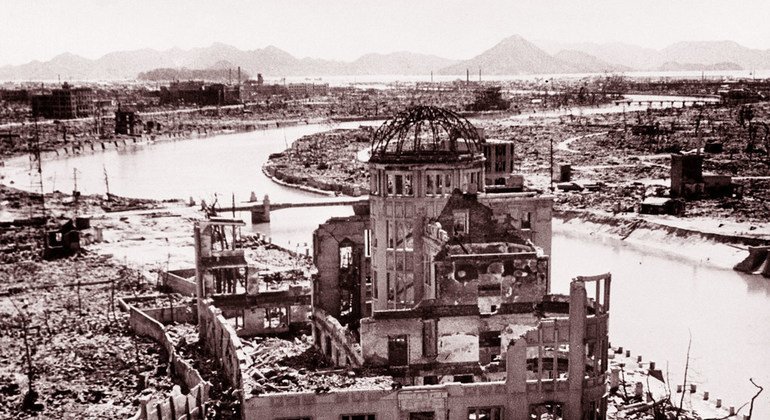

The creation of spatial distance between combatants is above all a characteristic of modern warfare and the development of distance weapons. The extent of interpersonal distance appears to be directly proportional to the range of the weapons. In the case of bows and arrows, the distance is still relatively small, as it was in the early development of rifles. Only in connection with another distancing principle, the integration into firmly established formations, did these weapons attain their historical significance. The situation is already different with weapons that have an effect at a greater distance, such as artillery in the Napoleonic Wars and World War I or the modern use of aircraft and rocket-propelled grenades. Bomber pilots can no longer see their opponent and perceive him as a human being. They drop their bombs on illuminated squares or leave target acquisition to the sensors of their weapons systems. In the most modern form of spatial distance, the enemy no longer appears as a human being at all, but only as a number and a diagram on computer screens.

One instrument for creating social distance is the degradation of the opponent by denying him his humanity. The demonization of the opponent is the prerequisite for his destruction. Thus, in the metaphoric of the Nazi regime, political opponents mutated into vermin and rats. In the political propaganda between the world wars, the ideological opponent was also assigned animal characteristics (“Russian bear”). The stigmatization of the opponent as a “machine being” also belongs to this category. In all these cases, the humanity of the opponent is negated, on the one hand, in order to strengthen the sense of belonging to one’s own community by spreading fear and terror, and on the other hand, in order to lift anthropological inhibitions against killing.

The Nazi concentration camps played a special role in the creation of social distance. In them, two mechanisms of action were applied: on the one hand, the organized and purposeful dehumanization of people, who were degraded to mere numbers by systematic terror. Their individuality was erased by pain and hunger to such an extent that in the end, they were only walking skeletons, “Muselmanen” (Sofsky, 1993, 229 ff.). On the other hand, a sophisticated form of “division of labour” was developed, especially in the pure extermination camps.

Inhibition to kill was also lowered in groups whose coherence and inner structure had a stronger effect than individuality. The importance of group cohesion was particularly evident in World War I. For many men, the war was the only place “where men could love passionately” (Stephan, 1998, 34 f.) What is meant, however, is not primarily homosexual love (although it always played a major role in men’s alliances), but the intoxicating, emotional bond with the community (ibid.). These men did not fight out of fear of their superiors or of punishment, but primarily out of comradely feelings: Just as they could rely on their comrades, the comrades should be able to rely on them. Possibly, this bond to the group through stress and practiced movements is more important and obvious than abstract ideals or interests for which the individual goes into battle. The decisive factor then is the community on a small scale, which must be defended.

The fear of one’s own death, the fear of being killed by another person, can only be countered in hopeless situations by killing the other person. The fear of one’s own death or the death of a member of the group leads directly to wanting to kill the cause of this fear of oneself. Fear of death and killing are directly related. The subjective impression arises, as if only the opponent brings one to kill oneself. In this case, the opponent seems to be responsible for the painful overcoming of one’s own inhibition to kill. This creates a boundless rage against him, because it is he through whose behaviour one’s own killing inhibition has been lifted. In the direct fight (“eye to eye”) for life and death, the fear of one’s own death becomes the furore of immoderate violence.

This “automatic killing” out of fear of one’s own death is described most vividly in Erich Maria Remarque’s novel Nothing New in the West. It says: “I think nothing, I make no decision – I thrust furiously and feel only how the body twitches and then softens and slumps.” And further: “If we were not automata at this moment, we would remain lying, exhausted, will-less. But we have pulled forward again, will-less and yet madly furious, wanting to kill, for that there are our mortal enemies now, their guns and shells aimed at us. We are numb dead men who can still run and kill by a dangerous spell” (Remarque, 1998).

If one assumes an anthropologically conditioned inhibition of killing in humans, one can furthermore interpret the mutilation of the opponent as a reaction to the fact that precisely despite the prohibition of killing “the other” was killed. The mutilation mitigates the guilt of killing a conspecific by the fact that this conspecific is no longer identifiable as a human being. In the act of killing a conspecific, its mutilation restores the distance between the opponents.

Whether the “lust” for killing described by Remarque is the result of a drive remains to be seen. It is more likely that the feelings felt in the existential situation of struggle are an expression of triumph over death because one’s own fear of death had to be held down in order to be able to act (Sofsky, 2002). If one assumes an anthropologically conditioned inhibition of killing in humans, one can furthermore interpret the mutilation of the opponent as a reaction to the fact that precisely despite the prohibition of killing “the other” was killed. The mutilation mitigates the guilt of killing a conspecific by the fact that this conspecific is no longer identifiable as a human being. In the act of killing a conspecific, its mutilation restores the distance between the opponents. Especially in the desecration of the dead, as often occurs in massacres, the motive of one’s own “apology” is revealed in the attempt to rob the opponent of even the last vestige of humanity.

Killing and proximity

In the case of groups and communities that are closely connected spatially and through neighbourhood relations, emerging socio-economic, religious-cultural, ethnic or political conflicts that are no longer negotiable can turn into extreme mutual anger.

So far, the creation of spatial and social distance has been discussed as a prerequisite for the individual as well as mass killing. In contrast, in situations characterized by great proximity, killing is often a means of re-establishing distance. It is a well-known fact that most murders committed by private individuals occur in the immediate social environment of the perpetrators. It is also no coincidence that the cruellest ethnic persecutions and exterminations take place between neighbouring or closely related population groups, as the example of Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks teach us. Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, spoke of the “narcissism of small differences” (Freud, 2001): The closer individuals and groups of people are to each other, the more disappointed expectations of love and happiness, unfulfilled claims, and hurt feelings of self-esteem play a decisive role in the mutual relationship. One cannot be as disappointed and hurt by “strangers,” by those who are not the same as by those who are closest to one (Mentzos, 2002).

Particularly in the case of groups and communities that are closely connected spatially and through neighbourhood relations, emerging socio-economic, religious-cultural, ethnic or political conflicts that are no longer negotiable can turn into extreme mutual anger. Because of manifold mutual dependencies, it may be necessary for such conflict situations to reassure oneself of one’s own identity by distancing oneself from the other group. One’s own self or that of the group finally experiences its own power and independence in a violent struggle, in which, precisely because of the dangerous proximity to other people or to the other group, not least one’s own elementary recognition is at stake (Altmeyer, 2002).

Victims

For Martin van Creveld, war does not begin when groups of people kill and murder others. Rather, a war begins at the point when the former risk being killed themselves. For van Creveld, those who kill for “base motives” are not belligerents, but butchers, murderers, and assassins (van Creveld 1998, 234-238). Despite all commonalities, the opinions of the theorists of the “New Wars” diverge widely at this point. While some emphasize the independence of violence, the excesses and irregularity of warfare, and pursue a culturally pessimistic approach (especially Sofsky), others primarily stress the aspect of the victim. War is understood here as an almost “sacred act” in defense of the existence of communities (van Creveld, 1998) and civilization (Keegan), characterized essentially by the soldierly willingness to sacrifice for the community (Ehrenreich, 1997 and Stephan, 1998). By considering only one side of the pair of opposites of victims and perpetrators, these theories transfigure war into a pure act of sacrifice, ultimately the most selfless of human activities (van Creveld, 1998).

The blurring of the contrast between victims and perpetrators in war is summarized by Thomas Kühne in the concept of the victim myth. In modern military life, this myth takes on the task of making an active killing in war socially acceptable, and of dissolving the contradiction between killing and being killed in a sacred aura.

The question, however, is who is a victim and who is a perpetrator in combat in wars. And when and where do the lines between the two blur? There is a long tradition of the myth of sacrifice, in which even the most barbaric destruction of the other was passed off as self-sacrifice for a higher cause. Heinrich Himmler, for example, spent some effort convincing his subordinates that the extermination of Jews in the gas chambers was in fact a heroic act. A distinguishing criterion obviously lies in whether one’s violent act is directed against the defenseless or against persons who have an opportunity for self-defense or escape. The blurring of the contrast between victims and perpetrators in war is summarized by Thomas Kühne in the concept of the victim myth. In modern military life, this myth takes on the task of making an active killing in war socially acceptable, and of dissolving the contradiction between killing and being killed in a sacred aura. The myth of sacrifice created a symbolic order in the moral and emotional conflict between the experience of death and killing, between feelings of omnipotence and powerlessness (Kühne, 1999 and 2001).

We will not abolish war in the 21st century, but we must limit it for reasons of self-preservation.

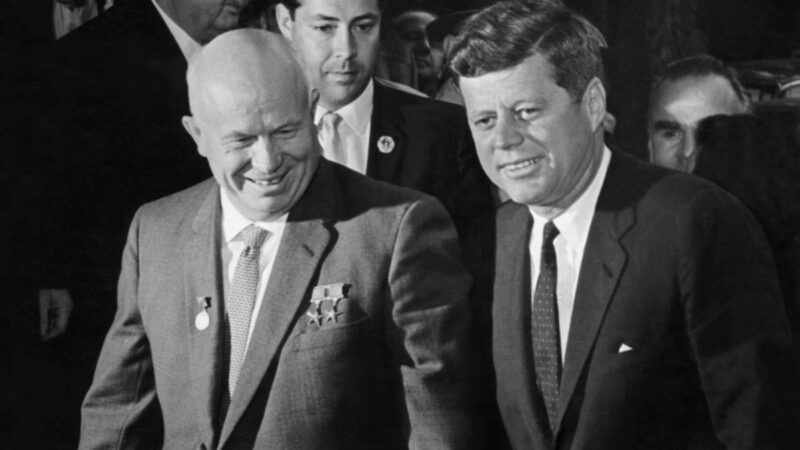

If we summarize, violence in war is possible because the other is no longer seen as equal, but a spatial or social distance makes it possible in the first place. Through our intelligence, even the physically weakest can defeat a stronger one and does not have to succumb to cut-throat competition. In part, violence also creates social distance in the first place, an aspect we find especially in civil wars. I am unsure whether violence has tended to increase or decrease in wars. Steven Pincker argued that, regardless of media portrayals, violence has decreased to a significant degree worldwide (Pinker, 2013) – to what extent the Ukraine war heralds a contrary trend is impossible to predict. What is likely, however, is that the wars of the future will revolve around ideas of order, around the resurgence of empires and civilizations that have been submerged in colonization and European-American hegemony and that are pushing onto the world stage (Herberg-Rothe & Son, 2018). Whether the possibility of overcoming violence or intensifying it follows from this will remain contested. A positive example could be the end of the Cold War, in which the countless overkill capabilities themselves overcame the antagonistic opposition between capitalism and communism, because the threat of the planet’s self-destruction made people realize not to fight a war with nuclear weapons. The other possibility remains that a new thirty-year war for recognition and order is looming. To be sure, war is not the “father of all things,” as Heraclitus opined. But its horrible destructiveness is nevertheless integrated with the dialectic of self-preservation – on the one hand through the increase of power and material, on the other hand, the preservation of an own physical or symbolic identity. This dialectical development can also contribute to the self-preservation of humankind, as it succeeded in the nuclear arms race of the Cold War, albeit with great luck in some cases. War as a means of self-preservation is abolished in the nuclear age. Even at the micro level, unleashing violence would endanger humanity’s self-preservation. We will not abolish war in the 21st century, but we must limit it for reasons of self-preservation.

References

Altmeyer, Martin (2000), Narzissmus und Objekt, Göttingen.

Ehrenreich, Barbara (1997), Blutrituale. Ursprung und Geschichte der Lust am Krieg, München.

Creveld, Martin van (1998), Die Zukunft des Krieges, München.

Eibl-Eibesfeldt, Irenäus (1984), Krieg und Frieden aus der Sicht der Verhaltensforschung, München.

Gray, Chris Habbles (1997), Postmodern War, London.

Grossman, Dave (1995), On Killing. The Psychological Costs of Learning to Kill in War and Society, Boston.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2007), Clausewitz’s puzzle. Oxford.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2017), Der Krieg. 2. Aufl. Frankfurt.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas and Son, Key-young (2018), Order wars and floating balance. How the rising powers are reshaping our worldview in the twenty-first century. New York.

Hondrich, Klaus (2002), Wieder Krieg, Frankfurt.

Kühne, Thomas (1999), Der Soldat. In: Frevert, Ute/Haupt, Heinz-Gerhard (Hrsg.), Der

Mensch des 20. Jahrhunderts, Frankfurt New York, 344-372.

Kühne, Thomas (2001), Lust und Leiden an der kriegerischen Gewalt.

Traditionen und Aneignungen des Opfermythos, ungedruckter Vortragstext zur Jahrestagung des Arbeitskreises Historische Friedensforschung “Vom massenhaften gegenseitigen Töten – oder: Wie die Erforschung des Krieges zum Kern kommt”, Ev. Akademie Loccum, 2.-4. Nov. 2001.

Mentzos, Stavros (2002), Der Krieg und seine psychosozialen Kosten, Göttingen.

Münkler, Herfried (1992), Gewalt und Ordnung, Frankfurt.

Orywal, Erwin u.a. (Hrsg.), (1995),, Krieg und Kampf. Die Gewalt in unseren Köpfen, Berlin.

Pinker, Steven (2013), Gewalt. Eine neue Geschichte der Menschheit. Frankfurt

Remarque, Erich Maria (1998), Im Westen nichts Neues, Köln.

Sofsky, Wolfgang (2002), Zeiten des Schreckens, Frankfurt.

Sofsky, Wolfgang (1993), Die Ordnung des Terrors, Frankfurt.

Sofsky, Wolfgang (1996), Traktat über die Gewalt, 2. Aufl., Frankfurt.

Stephan, Cora (1998), Das Handwerk des Krieges, Berlin.

[powerkit_button size=”lg” style=”info” block=”true” url=”https://admin.thepeninsula.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/TPF-Research-Paper-Killing-in-War-1.pdf” target=”_blank” nofollow=”false”]

Download

[/powerkit_button]