A persistent socio-economic issue requiring ongoing attention is the need for specific legislation to safeguard the social security of women workers in the “unorganised” sector. Although the government has expressed its aim to implement a National Policy for Domestic Workers to provide protection and social security benefits, it remains largely unrealised as a deferred vision. This highlights and clearly emphasises the neglect of the workforce within the “grey economy”, as termed by UN Women.[1]

The Gendered, Unregulated, and Unorganised Workforce

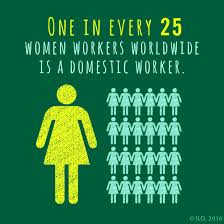

According to data from the e-eShram portal, which maintains records of the unorganised workforce, the total number of women domestic and household workers registered on the portal as of March 2023 is 2.67 crore (out of a total of 2.69 crore). This staggering figure not only highlights the economic vulnerability faced by women but also the gender disparity.

However, what is more alarming is that these statistics reflect only the registered segment of the workforce. The absence of reliable data on unregistered domestic and household workers raises serious concerns regarding the invisibility and exploitation of millions who remain outside the ambit of any regulatory or welfare framework.

International Legal Framework: The ILO Convention

Article 1 of the Domestic Workers Convention of 2011[2] (Convention 189) defines domestic work as work performed in the household, and a domestic worker as a person engaged in domestic work with an employment relationship, and carrying it out on an occupational basis.[3] The Convention mandates the protection of domestic workers by ensuring equal treatment, decent working conditions, fair wages, and prohibiting all forms of abuse and exploitation.

The Domestic Workers Recommendation, which supplements Convention 189, further recommends, inter alia, the creation of a model employment contract, a minimum standard for “live-in domestic workers”, and the promotion of awareness and training programmes.

India’s Position

Although India is a signatory to the Convention, its continued abstention from ratification has constrained the formulation and effective implementation of a comprehensive national policy for domestic workers, despite repeated governmental declarations of commitment in this regard.

Entry 24 of List III (Concurrent List) of the Constitution empowers both Parliament and State Legislatures to enact laws on labour welfare. However, this concurrent competence has resulted only in a fragmented legal framework, marked by uneven levels of protection. In the absence of comprehensive central legislation, domestic workers are left in a legal vacuum, with existing legal frameworks offering only minimal and indirect protection.

Existing Legal Protection in India

1. The Unorganised Social Security Act of 2008[4]

The Unorganised Social Security Act of 2008 is the first legislation to recognise “unorganised workers.” Section 2(n), which defines the wage worker, includes “workers employed by households, including domestic workers.”

Section 2(m)[5] further states that the unorganised workers are the workforce not covered by any of the social security legislations, such as:

- Employee’s Compensation Act, 1923 (3 of 1923),

- The Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 (14 of 1947),

- The Employees’ State Insurance Act, 1948 (34 of 1948),

- The Employees Provident Funds and Miscellaneous Provision Act, 1952 (19 of 1952),

- The Maternity Benefit Act, 1961 (53 of 1961) and

- The Payment of Gratuity Act, 1972 (39 of 1972)[6]

2. Other Statutory Protections

According to the Child Labour (Prohibition & Regulation) Act, 1986, employment of children below the ages of 14 and 15 years in certain prohibited occupations, including domestic work or service, is prohibited.

The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition & Redressal) Act, 2013, extends protection to women engaged in household work against sexual harassment under Section 2(e), and provides redressal through an inquiry into the complaint under Section 11.[7]

Section 27 [8] of the Minimum Wages Act, 1948,[9] empowers the appropriate State governments to fix a minimum wage by adding an employee to the Schedule. Thus, some states have added the category of “domestic work” into the schedule to provide a statutory protection of minimum wages through State laws. According to the PIB[10], the State Governments of Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Odisha, Rajasthan, Haryana, Punjab, Tamil Nadu and Tripura have included domestic workers in the schedule of the Minimum Wages Act.

The Conundrum between Fair Wages & Minimum Wages

A common misunderstanding about the minimum wage is that it is synonymous with a fair wage. While minimum wages provide a baseline, they do not necessarily equate to fair wages. The factors used to determine and compute a minimum wage change with the inevitable fluctuations in economic factors, such as the cost of living, employer capacity, purchasing power, and other market conditions. Wage is not something that is required for mere existence but is necessary for leading a decent livelihood, and that is what amounts to “fair wage.” The Supreme Court in the landmark cases of Maneka Gandhi v Union of India[11] and Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation[12] has held that “right to life under Article 21 is not just about physical survival but includes the right to live with human dignity.

The Hon’ble Supreme Court, while recently hearing the case of Ajay Malik v. State of Uttarakhand,[13] where it directed the rescue and rehabilitation of a woman who was abused while employed as a domestic worker, noted the “incontrovertible demand” for a national domestic worker’s law. The court in this case also highlighted the plethora of attempts taken by the Parliament to legislate on this matter through various bills, such as

- The Domestic Workers (Conditions of Employment) Bill of 1959,

- The House Workers (Conditions of Service) Bill of 1989,

- The Housemaids and Domestic Workers (Conditions of Service and Welfare) Bill, 2004,

- The Domestic Workers (Registration, Social Security and Welfare) Bill, 2008,

- The Domestic Workers (Decent Working Conditions) Bill of 2015,

- The Domestic Workers Welfare Bill, 2016,

- The Domestic Workers (Regulation of Work and Social Security) Bill, 2017, was never enacted afterwards.

The National Policy on Domestic Workers calls for the inclusion of social security protections, such as “life and disability cover, health and maternity benefits & old age protection,” for domestic workers within the existing legislation of the Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act, 2008. However, with the enactment of The Code on Social Security, 2020 (CoSS), the 2008 Act is repealed, and its provisions are subsumed in the Code.

The social security schemes are operating in the interim through the executive scheme (eShram)[14].

Why do Domestic workers require a central legislation?

The key question is why domestic workers require central legislation and what objective it aims to serve. The scope of the term domestic worker is so broad that it includes chores ranging from washing utensils and cleaning the house to even serving as caretakers; ironically, their scope for legal protection remained confined due to their engagement in private homes. This leads to the perception that any form of regulation is “illegitimate or an intervention into the private affairs.”[15] However, the private nature of labour naturally places the domestic workers in a vulnerable position, often prone to abuse by the employers. Hence, the objective of the law should not be just to prevent abuse against domestic workers and to ensure a social welfare scheme, but also to empower the section to adopt vocational or skill training to equip them with the means for a self-sufficient life.

Policy Recommendations

The problems faced by the domestic workers cannot be tackled in isolation; they require not only the legislation of a central law but also its effective implementation. This can be done with the assimilation of the new mandates into the existing structure. The central legislation should facilitate the following:

- Mandatory registration of domestic workers in the E-Shram portal, conferring an obligation upon the employer to register their domestic workers in the national register of the E-Shram portal, in case of failure on the part of the workers.

- Establish a national helpline number with a domestic workers’ welfare board to report and track the incidents of both violence by and against the domestic workers.

- Ensuring skill training for domestic workers through self-help groups, as well as regional skill-training programmes under the supervision of taluk-level officers, to prevent stagnation in centralised schemes.

Endnotes:

[1] UN Women, “Women in Informal Economy,” UN Women, available at https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/women-in-informal-economy

(last visited Oct. 5, 2025).

[2] International Labour Organization, Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (C-189), Article 1.

[3] International Labour Organization, Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189), ILO NormLEX, Instrument ID: 2551460.http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:2551460:NO

[4] The Unorganized Workers’ Social Security Act, 2008, No. 33 of 2008.https://labour.gov.in/sites/default/files/unorganised_workers_social_security_act_2008.pdf

[5] The Unorganized Workers’ Social Security Act, 2008, No. 33 of 2008, §2(m).

[6] Ministry of Labour & Employment, Government of India, “Unorganized Worker” (labour.gov.in).

[7] The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition & Redressal) Act, 2013, No. 14 of 2013 §11.

[8] The Minimum Wages Act, 1948, No. 11 of 1948, §27.

[9] The Minimum Wages Act, 1948, No. 11 of 1948., https://clc.gov.in/clc/sites/default/files/MinimumWagesact.pdf

[10]Press Information Bureau, Government of India, “National Policy for Domestic Workers” (Press Release, 12 September 2019). https://www.pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1564261

[11] Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, (1978) 1 SCC 248.

[12] Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation, (1985) 3 SCC 545

[13] Ajay Malik v. State of Uttarakhand, 2025 SCC OnLine SC 185

[14] Ministry of Labour & Employment, Government of India, e-Shram Portal, https://eshram.gov.in/

[15] Vanessa H. May, Unprotected Labor: Household Workers, Politics, And Middle-Class Reform in New York, 1870–1940, 12 (2011)

Leave a Reply