What was the voter turnout?

The big change is that Harris, so far, has lost 9 million voters since 2020, while Trump has gained only 1.2 million. Harris’s count of lost votes will decline as the final votes come in, but the bigger story remains that Harris lost more votes than Trump gained.

Voter turnout is NOT final, but it is likely between 153 and 156 million, down from 2020 but still the second-highest percentage turnout in 100 years. At a minimum, 107 million adults did not vote (88 million of whom are “eligible” to vote). Thus, 41% or more of the adult population and 36% of the eligible voters did not vote.

Using the percentage of voter groups who voted for Trump is misleading. The news remains that the significant change is the loss of Harris voters.

What were the economic issues?

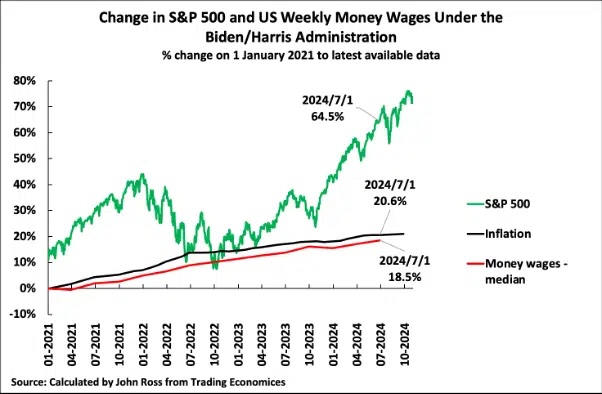

Daily survival has become a serious problem for the bottom 65% due, specifically, to the inflation of grocery items and increasing mortgage payments and rent. Aggregate figures don’t reflect this reality.

Workers’ actual standard of living was worse under Biden than under Trump.

Real wages in the US remain lower than they were a half-century ago.

Are there differences between Democrats and Republicans?

US electoral parties are NOT like those in Europe – they have always been a different version of bourgeois electoral systems. Both major US parties are corporations, not parties with memberships, ideologies, and programs. They are designed like a marketplace of individuals preening for the Presidency, much like the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show, but only held every four years.

The Democrats turned over their foreign policy to the CNAS group of neo-con warmongers who will now be displaced.

The Republicans are also not an actual party; Trump proved this, and what is next for Republicans post-Trump is also uncertain.

What are the class shifts in the US?

There is a new stratification of the bourgeoisie, with billionaires as a new factor. The increasingly dominant discourse amongst the capitalist class has the wherewithal to exert its influence.

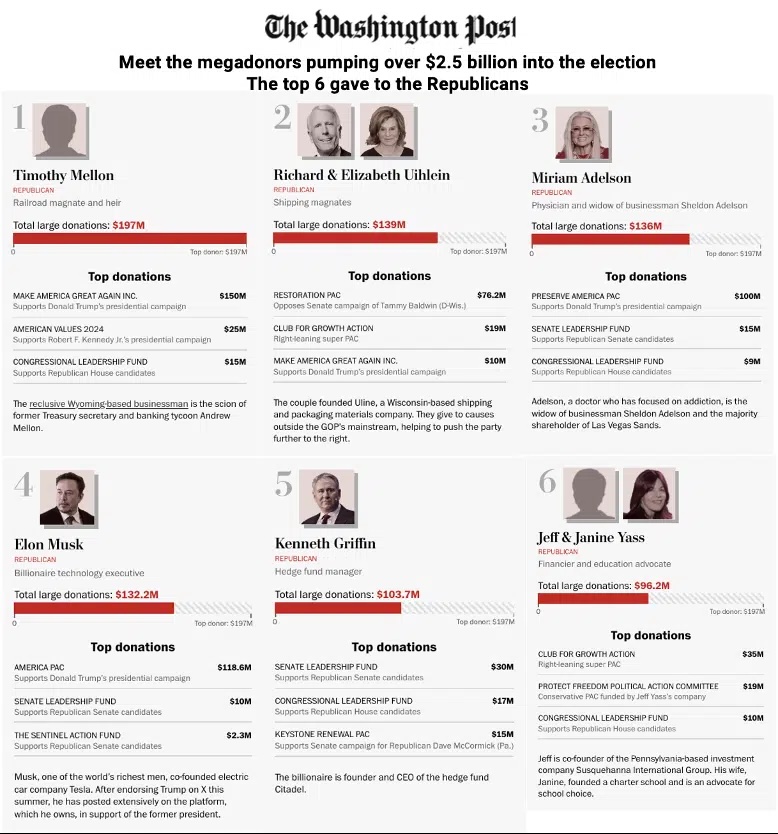

Fifty Billionaires put 2.5 billion US dollars, 45% of the 5.5 billion total, into the Presidential election. Of this, 1.6 billion went to the Republicans, 750 million to the Democrats, and the rest to both. The total spent on the election, in all races, was 16 billion, a sign of a kleptocracy, not a thriving democracy.

washingtonpost.com/elections/interactive/2024/biggest-campaign-donors-election-2024

washingtonpost.com/elections/interactive/2024/biggest-campaign-donors-election-2024

There is a concerted effort by a section of libertarian tech billionaires, including Thiel and Musk, to have their hands directly on the levers of the state to control the race for global domination of AI. They believe that they alone should control the advances in the AI space for the world and that the initial next step is what is called Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). These megalomaniacs believe this will begin the control of humans by machine intelligence and, perhaps, in their perverse dreams, the end of humanity.

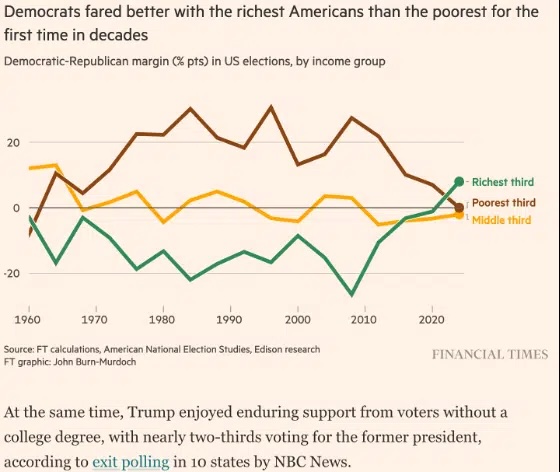

A growing number of lesser capitalists, such as multimillionaires, are now being lumped into the upper middle class and the wealthiest one-third of voters. One very important trend to note is that in the last fifteen years, the richest one-third have switched allegiance from Republicans to Democrats.

Why did Harris lose 6 to 9 million votes?

Workers were worse off, wages did not keep up, and inflation left a long, lingering impact. Some of the youth vote left for economic reasons. Others were disillusioned and demoralised by the full-throated support of the genocidal war in Gaza by the Democratic Party. Muslims, while a small group, voted for a third party or Trump.

Despite the fabrications of the Democratic Party corporate handlers, Harris was, in fact, inauthentic, unlikeable, shallow, and could not mask her history as a prosecutor who spent her life attacking the rights of the poor.

Dissatisfaction with many Western elected parties is growing – Conservative in the UK, Centre Right in France, right-wing in Germany – all thrown out. Biden left a demoralised Democratic Party and left too late.

Fear-mongering about fascism was core to the rhetoric of the Democrats, even though no one knows what the term means. Some voters became annoyed at the harassment by the liberals to vote for them since they were the last rail of defence against fascism. Many people did not believe Trump was, in fact, a fascist, nor did they believe that every one of their family members who listened to Trump was a fascist.

Apathy is growing and remains a real issue.

Probably over a million stayed at home as they could not stomach the Democratic Party’s gleeful support for Genocide. Trump’s victory in Michigan was certainly due to this issue.

Harris played to and fawned over the war criminal Dick Cheney, the architect of the invasion of Iraq and a historic right-wing enemy of the Democrats. We don’t know how many voters left in disgust.

Why did Trump gain votes?

Trump took advantage of working-class dissatisfaction. Even so, he only gained less than 2 million total new votes. There is no evidence of a widescale shift of working-class votes to the Republicans in this election.

Working-class women voted for local candidates supporting abortion but voted for Trump for economic and other reasons. Others voted on local issues important to them and then voted for Trump as they felt that despite his unsavoury behaviours, he was more committed to “shaking things up”.

The billionaire class made sure that Trump had ample funds. Elon Musk’s America Pac spent $118 million handling field operations for the Trump campaign, an unusual role for a super PAC.

From 2008 to 2020, there was a decline in the percentage of voters supporting the Democrats amongst the bottom 1/3 of income earners in the US.

ft.com/content/6de668c7-64e9-4196-b2c5-9ceca966fe3f

ft.com/content/6de668c7-64e9-4196-b2c5-9ceca966fe3f

Too little data is available now to provide a detailed answer about the relatively insignificant number of voters who voted Democrat in 2020 and Republican in 2024.

What is the assessment of the new cabinet positions announced?

Trump’s sixteen appointments to date are all vocal supporters of genocide in Palestine. In the United States, there are both Jewish and Christian Zionists. Trump has appointed several Christian Zionists. The majority are China hawks.

When analysed from a US statecraft point of view, many are extremely underwhelming candidates. These include:

- Secretary of State: Senator Marco Rubio: He is a rigid, fierce anti-communist.

- Secretary of Defense: Pete Hegseth, an Army National Guard veteran and Fox News host: He is divisive and has no high-level military experience.

- Attorney General: Representative Matt Gaetz of Florida: He has no experience in the Department of Justice and has had past legal controversies.

- Director of National Intelligence: Former Representative Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii. She has no intelligence background but is perhaps less rigid on international issues, a non-interventionist, and has a friendship with Indian Prime Minister Modi.

- Ambassador to the United Nations: Representative Elise Stefanik of New York. She is an extreme Zionist, has near zero diplomatic experience, and has focused only on domestic issues, but is loyal to Trump.

- Secretary of Homeland Security: South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem. She lacks national government experience, and her actions have veered toward radical anti-federalism.

Due to some of these appointments, US stature in international affairs will likely diminish.

Trump has brilliantly dismissed the extremely dangerous Pompeo. He has made it clear that few from the first inner group of his cabinet and advisors will return. The world will not miss them. Yet there is little evidence to suggest that Trump has the capacity to lead any group successfully for even an intermediate period. He is known for turning on people and turning them against each other.

How do we interpret the vote?

A significant section of the working class understandably abandoned the Democrats in this election.

There is not a major right-wing shift in US attitudes, but there is a real base for the right.

The Democratic Party elite is completely divorced from the masses. Parading the loyal royal cultural elite like Taylor Swift, Beyonce, and Bruce Springsteen reeked of wealth, opulence, and tone-deafness.

Apathy should not be understated. At least 88 million didn’t vote, with a further 19 million disenfranchised.

Third parties are structurally prevented from winning even a single state in a presidential election. They are structurally locked out of Congress. The United States has locked in a two-party system. Most voters have been captured by this belief.

Small exceptions to this are wealthy candidates like Ross Perot in 1992 and Robert Kennedy Junior.

There was huge intimidation at the end against supporters of third-party candidates, which depressed their vote even more than usual. In this just-held election, the Party for Liberation and Socialism Candidate Claudia Cruz received 134,348 votes so far. Claudia Cruz’s 134 thousand votes is the highest number of votes for an explicit communist in American history. It exceeds the CPUSA’s William Z. Foster’s previous record of 120,000 votes in 1932. The 1932 vote was a higher percentage of the population as the US was smaller in 1932. These facts are a reminder of the long-term campaign of anti-communism within the US.

Capital is clearly happy with Trump’s win, as evidenced by the November 6th celebration rally on Wall Street. They disagree with the liberal hype that he will bring an end to American society.

Despite the lies of the liberals, the facts are that Trump formally initiated the New Cold War on China. His inner team are more fiercely anti-China than the Democrats, who are more bound to the Ukraine War.

Trump has fewer restraints, controlling the Senate, House, Supreme Court, and Presidency.

He could well launch a Third World War. It would be a mistake to underestimate this danger.

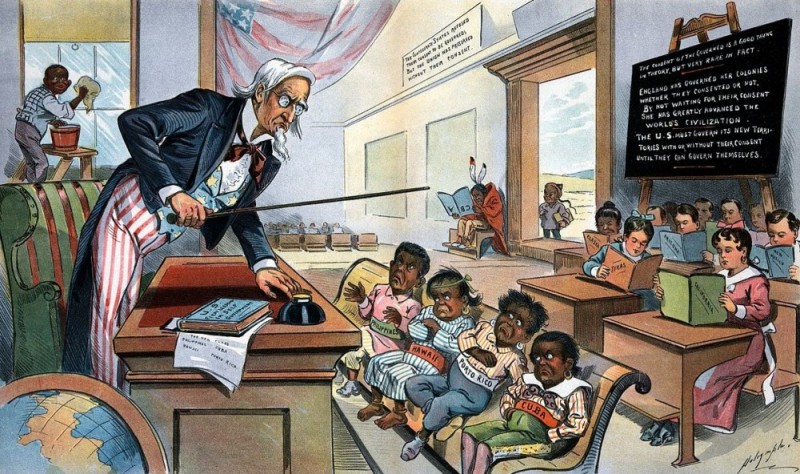

Other things people outside the US should know

There is a tendency in some parts of the Global South to have a simplistic and false analysis that any enemy of the liberals is a friend of the Global South. This is a severely flawed argument. The imperialist far-right is not a good guy, a cultural conservative who wants to protect families and cultural life. Inside the US, conservative culture is tightly tied to slavery and genocide. It is misogynistic, racist, militaristic, and reactionary. We should not confuse the histories of Iran, Turkey, India, Ghana, and China with those of the US.

Welcoming divisions in the enemy camp is often entirely correct. But Communists, socialists, and true democrats do not support reactionary views and always side with the people, not the far-right ideologues.

There is also great confusion about MAGA and MAGA-Communism. First, Make America Great Again (MAGA) means returning (the second “A” in MAGA) to the full glory of the US industrial past. But what was that past? It was, in fact, the total economic, political, military, and racial subordination of the peoples of the Global South states to the US. It was the century of humiliation in China. This is not a return to be welcomed by history. MAGA is a profoundly reactionary, unacceptable outcome and concept.

One of the greatest poets in the United States is Langston Hughes. One of his poems was called “Let America Be America Again.” But this was a parody as the actual statement was made in the refrain, “America Never Was America to Me”. The meaning of this poem was the false portrayal of the United States as ever having a glorious past, which was never true for the slaves or the working class.

Second, there are a handful of personalities in the US who have taken the great word communism and sullied it with the idea of returning to this falsely idealised America. The old “strong” American industry was built on the backs of low-paid workers in the mines in Africa and elsewhere.

Desiring a real communist path is a good thing. But tying it to an imperialist past, a past of violence, with reactionary views is the opposite path taken by Lenin, Mao, and Fidel.

There is also a dangerous tendency to simply reject the liberal concepts of identity politics and embrace the values of far-right conservatism while lacking scientific thinking about the plight of women and other vulnerable groups.

The CPC led the country in the first national Soviets in Ruijin in the struggle to abolish the prejudices of feudalism and emancipate women and national minorities in China. However, these rights have not yet been achieved in many countries, as there has been no communist revolution.

True Communism is the path to advancing the overall interests of the working class in all countries, including women, national minorities, and other vulnerable groups.

The Republican voter base in class-terms is the lower-middle class, which is overwhelmingly white, suburban, rural. It is amplified by fundamentalist Christians and the Republican regional strongholds.

There are six “ideological” trends, all extreme right, in the Republican camp:

- Populist demagogues

- Extreme Libertarians

- Fanatical Christian-Zionists

- Virulent anti-communists

- Dangerous AI-obsessed Tech billionaires

- Complex conservatives

The US economy will continue to perform poorly but better than the rest of the West. It will continue to use its dollar hegemony, reinforced with sanctions, to remove hundreds of billions from the Global South and to force Europe, Australia, and Japan to subordinate their economic interests to those of the US.

The actual US budget for the military was $1.8 trillion last year. Significant cuts seem improbable.

There is now a permanent Black upper middle class that produces a Black mis-leadership. This mis-leadership group has created two decades of Black war criminals and apologists for empire. The rise of this mis-leadership gang, however, should not overshadow the fact that most blacks remain oppressed and exploited.

The anti-immigrant politics in the U.S. is directed primarily at undocumented immigrants from Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean.

But there is a false belief that all immigrants in the US are working class and progressive – it is just not true. An important stratum of non-working-class immigrants in the US are amongst the most virulent defenders of US atrocities in the world.

There is a belief that there is a conspiracy of some secret group of members of the military and government that decide most things, which they call the Deep State. This is a lazy concept. It denies that all states have a class character and permanent army. In the US, it has been estimated that over 5 million people have security clearance, and many have near-lifetime employment. There is no need for conspiracy theories. The US does have an advanced state that functions on behalf of capital. This state manages the affairs of the often-competing large capitalists and is now increasingly primarily favouring the billionaires amongst the capitalist class. Thus, a better way to see the US State is through the lens of Mao, Lenin, and Marx and not as some inexplicable conspiracy.

There is a special relationship between the US and Israel, both extreme white-settler states. In the US alone, over 30 House, Senate, and cabinet members are dual citizens of the US and Israel. Israel does not control the US, BUT they are socially a duopoly.

They are the CORE of Ring 1 of the Global North, the core of the imperialist bloc, along with the UK, Canada, and Australia.

The long-term trend is clear – bourgeois liberal democracy is failing globally.

What is the domestic consequence of the vote?

Since 2016, the very top of the capitalist class has led and mobilised a neo-fascist movement. Increasing levels of force and lawfare will now be used internally inside the US.

Trump himself is not a fascist per se. He is super-egoistic and believes he can act with near absolute impunity.

But he is riding on, and a beneficiary of changing class phenomena.

Fascism is not so much an ideology as a structural class relationship in which the lower-middle class, which has a revanchist ideology, is mobilized by big capital during a period of internal and external disequilibrium.

The New York Times and Financial Times use the word fascism as a scare tactic to maintain their role and influence in the state. Neo-fascism is a more precise word than fascism at this moment to describe the changes in the US.

Historically, there are a few things that are necessary to define a fully fascist state in imperialist countries. One is that the state uses methods of control it would typically use only for its colonies and neo-colonies, i.e., extreme widespread violence and force. The other is that they resort to the overthrow of the constitution.

The Constitution is unlikely to be changed directly. However, the original Constitution, an eighteenth-century document, has many gaps that can be exploited.

Radical and extreme legal changes are thus probable. There will be a reversal of 70 years of civil rights.

Overall, it remains to be seen how far the capitalist class is willing to go.

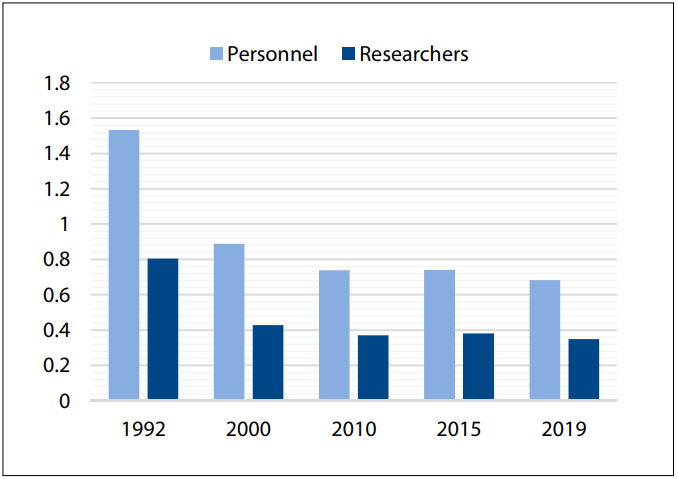

State capacity in many areas other than defence and border police will be diminished. Trump 1 saw big cuts in the State Department. Even with Rubio present, it is unlikely to be refunded to its old level.

The Billionaires will play a direct role in key tasks, from meeting Zelensky to chain-sawing government departments. Some departments, like Agriculture, Education, and Health and Human Services, are, in fact, decrepit, corrupt and dysfunctional. But a billionaire-led revamp will result in an unsavoury privatized equally dysfunctional capitalist state bureaucracy.

Trump is committed to a long-term isolationist strategy. But the US has over 900 military bases abroad. It has fully supported the expansion of Israel’s War in the Middle East, building up its military in the process.

Trump will not block the infrastructure projects that were voted in during Biden. The US recognises that its lost manufacturing capacity is a strategic deficit in military supply.

The brunt of the cutbacks will still increase the suffering of the 150 million working-class poor in the US.

The Left will be even more subjected to severe repression. Rubio is salivating.

What are the possible international consequences?

Despite the recent Zelensky meeting, the US will probably push a cease-fire and curtail the Ukraine war. Crimea is off the table. The current military lines will be the starting point. Doing this could reduce the immediate danger of a nuclear war. In April of this year, both Vance and Rubio voted against the 95-billion-dollar US military aid bill for Ukraine.

With Israel, there are three main possibilities:

- Trump curtails Netanyahu and calls for an end to Lebanon, no regime change in Iran, and an unjust peace agreement.

- He falls prey to the Christian Zionists and continues Genocide against Palestine.

- He goes against his no-war statements and approves an escalation with Iran.

We don’t know, but option one is not impossible. Trump wants a deal with Saudi Arabia.

A few days ago, MBS was forced to call it a Genocide, a rare statement from a long-term US ally.

With China, there are also three possibilities:

- Trump says tariffs are his favourite word in the English language and wants to increase them and eliminate domestic taxes.

- Rubio and other super China-hating cabinet members push him to escalate.

- US national security elements and US tech moguls like Peter Thiel push US military preparations.

On the question of Taiwan, some in the Global South fall for the liberal messaging soundbite in the West that Trump, the dealmaker, will sell Taiwan for a fee. This would bring strong resistance from the US military and large sections of the anti-communist members of his core group. This is a very unlikely case.

The world should not be confused if Trump does initiate a ceasefire in Ukraine and pressures Netanyahu to curtail the Genocide. Neither of these actions reverses the long-term trend of the US towards militarization against China. Nothing Trump does will turn around anaemic long-term US economic growth.

China is still on target to surpass the US in current exchange rate GDP within 10 years.

The US state is still on a long-term course to use its self-perceived military supremacy to destroy what it perceives as the Eurasian threat. It remains committed to dismembering the Russian Federation and overthrowing the CPC. The imperialists believe this is the path to a thousand-year reign of unilateral power.

The US will continue, unabated, its strategy of seeking nuclear primacy and what is called the “counterforce” strategy, which plans on the use of a first strike or launch of nuclear weapons. Evidence of these dangerous changes in US military strategy can be seen by their unilateral withdrawal from the following treaties:

- 2002 (Bush): the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty.

- 2019 (Trump): the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty

- 2020 (Trump): the Open Skies treaty

Tucker Carlson has Trump’s ear for now and is not a proponent of military conflict.

In 2023, a four-star general, Minihan, claimed that the US would be in a hot war with China in 2025. These are not accidental statements.

It is unknown if Rubio, some of the far-right libertarians, and CNAS-influenced military forces can overcome Trump’s dislike of military conflict.

The US is likely to increase its attention on Latin America and increase support for the far right like Bolsonaro and Milei.

Large-scale aid to Africa is not likely to happen. The Angola railway project is now improbable.

Final comments

The US state is still on a long-term course to use its self-perceived military supremacy to destroy the Eurasian threat.

The US has adopted counterforce and nuclear supremacy as its prime military strategy.

The threat of war has not changed due to a new administration. Only, perhaps, the speed at which it will be accomplished.

The economic and political assaults against the US working class will escalate, especially against progressives.

The state will continue to tighten its grip on the so-called bourgeois democratic freedoms by further restricting voting rights, civil rights, and freedom of speech.

This article was published earlier on MRonline

The article is republished underCreative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.