Rise of Multipolar World Order – www.newsvoyagernet.com

The irrational amounts that the Soviet Union allocated to its defense budget not only represented a huge burden on its economy, but imposed a tremendous sacrifice on the standard of living of its citizens. Subsidies to the rest of the members of the Soviet bloc had to be added to this bill.

Such amounts were barely sustainable for a country that, as from the first half of the 1960s, was subjected to a continuous economic stagnation. This situation became aggravated by the strong decline of oil prices, USSR’s main export, since the mid 1980s. The reescalation of the Cold War undertaken by Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, particularly the latter, put in motion an American military buildup, that could not be matched by Moscow.

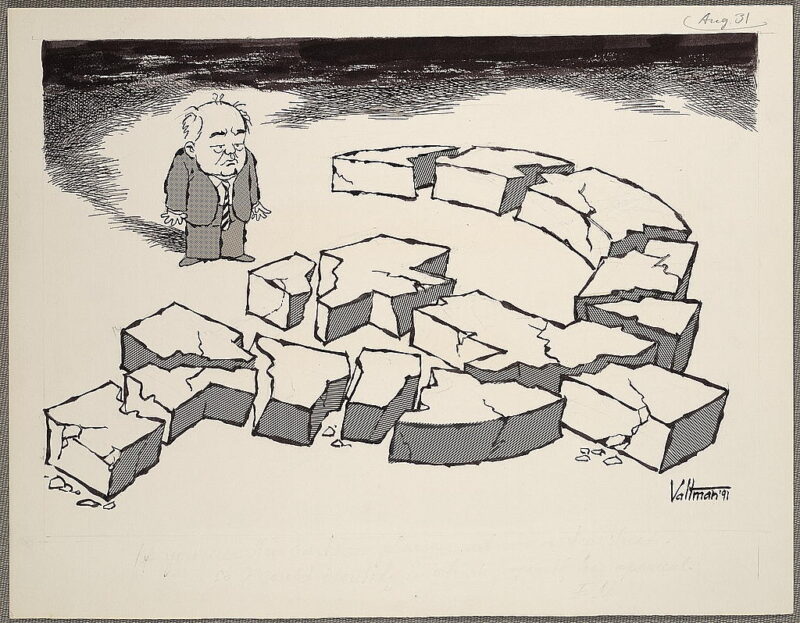

With the intention of avoiding the implosion of its system, Moscow triggered a reform process that attained none other than accelerating such outcome. Indeed, Mikhail Gorbachev opened the pressure cooker hoping to liberate, in a controlled manner, the force contained in its interior. Once liberated, however, this force swept away with everything on its path. Initially came its European satellites, subsequently Gorbachev’s power base, and, finally, the Soviet Union itself. The Soviet system had reached the point where it could not survive without changes, but neither could assimilate them. In other words, it had exhausted its survival capacity.

Without a shot being fired, Washington had won the Cold War. The exuberant sentiment of triumph therein derived translated into the “end of history” thesis. Having defeated its ideological rival, liberalism had become the final point in the ideological evolution of humanity. If anything, tough, the years that followed to the Soviet implosion were marred by trauma and conflict. In the essential, however, the idea that the world was homogenizing under the liberal credo was correct.

On the one hand, indeed, the multilateral institutions, systems of alliances and rules of the game created by the United States shortly after World War II, or in subsequent years, allowed for a global governance architecture. A rules based liberal international order imposed itself over the world. On the other hand, the so-called Washington Consensus became a market economy’s recipe of universal application. This homogenization process was helped by two additional factors. First, the seven largest economies that followed the U.S., were industrialized democracies firmly supportive of its leadership. Second, globalization in its initial stage acted as a sort of planetary transmission belt that spread the symbols, uses, and values of the leading power.

The new millennium thus arrived with an all-powerful America, whose liberal imprint was homogenizing the planet. The United States had indeed attained global hegemony, and Fukuyama’s end of history thesis seemed to reflect the emerging reality.

But things turned out to be more complex than this, and the history of the end of history proved out to be a brief one. In a few years’ time, global “Pax Americana” began to be challenged by the presence of a powerful rival that seemed to have emerged out of the blue: China. How had this happened?

Beginning the 1970s, Beijing and Washington had reached a simple but transformative agreement. Henceforward, the United States would recognize the Chinese Communist regime as China’s legitimate government. Meanwhile, China would no longer seek to constrain America’s leadership in Asia. By extension, this provided China with an economic opening to the West. Although it would be only after Deng Xiaoping’s arrival to power, that the real meaning of the latter became evident.

In spite of the multiple challenges encountered along the way, both the United States and China made a deliberate effort to remain within the road opened in 1972. Their agreement showed to be not only highly resilient, but able to evolve amid changing circumstances. The year 2008, however, became an inflexion point within their relationship. From then onwards, everything began to unravel. Why was it so?

The answer may be found in a notion familiar to the Chinese mentality, but alien to the Western one – the shi. This concept can be synthesized as an alignment of forces able to shape a new situation. More generally, it encompasses ideas such as momentum, strategic advantage, or propensity for things to happen. Which were, hence, the alignment of forces that materialized in that particular year? There were straightforward answers to that question: The U.S.’ financial excesses that produced the world’s worst financial crisis since 1929; Beijing’s sweeping efficiency in overcoming the risk of contagion from this crisis; China’s capability to maintain its economic growth, which helped preventing a major global economic downturn; and concomitantly, the highly successful Beijing Olympic games of that year, which provided the country with a tremendous self-esteem boost.

The United States, indeed, had proven not to be the colossus that the Chinese had presumed, while China itself turned out to be much stronger than assumed. This implied that the U.S. was passing its peak as a superpower, and that the curves of the Chinese ascension and the American decline, were about to cross each other. Deng Xiaoping’s advice for future leadership generations, had emphasized the need of preserving a low profile, while waiting for the attainment of a position of strength. In Chinese eyes, 2008 seemed to show that China was muscular enough to act more boldly. Moreover, with the shi in motion, momentum had to be exploited.

Beijing’s post-2008 assertiveness became much bolder after Xi Jinping’s arrival to power in 2012-2013. China, in his mind, was ready to contend for global leadership. More to the point within its own region, China’s centrality and the perception of the U.S. as an alien power, had to translate into pushing out America’s presence.

Challenged by China, Washington reacted forcefully. Chinese perceptions run counter to the fact that the U.S.’ had been a major power in East Asia since 1854, which translated into countless loss of American lives in four wars. Moreover, safeguarding the freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, a key principle within the rules based liberal international order, provided a strong sense of staying power. This was reinforced by the fact that America’s global leadership was also at stake, thus requiring not to yield presence in that area for reputational reasons. The containment of Beijing’s ascendancy, became thus a priority for Washington.

However, accommodating two behemoths that feel entitled to pre-eminence is a daunting task. Specially so, when one of them feels under threat of exclusion from the region, and the other feels that its emergence is being constrained. On top, both remain prisoners of their history and of their national myths. This makes them incapable of looking at the facts, without distorting them with the subjective lenses of their perceived sense of mission and superiority.

War ensuing, under those circumstances, is an ongoing risk. But if war is a possibility, Cold War is already a fact. This implies a multifaceted wrestle in which geopolitics, technology, trade, finances, alliances, and warfare capabilities are all involved. And even if important convergent interest between them still remains in place, ties are being cut by the day. As a matter of fact, if in the past economic interdependence helped to shield from geopolitical dissonances, the opposite is the case today. Indeed, a whole array of zero-sum geopolitical controversies are rapidly curtailing economic links.

The U.S., particularly during the Biden administration, chose to contain China through a regional architecture of alliances and by way of linking NATO with Indo-Pacific problems and selective regional allies. The common denominator that gathers them together is the preservation of the rules based liberal international order. An order, threatened by China’s geostrategic regional expansionism.

However, China itself is not short of allies. A revisionist axis, that aims at ending the rules based liberal international order, has taken shape. The same tries to throw back American power and to create its own spheres of influence. This axis represents a competing center of gravity, where countries dissatisfied with the prevailing international order can turn to. Together with China two additional Asia-Pacific powers, Russia and North Korea, are part of this bloc.

Trump’s return to the White House might change the prevailing regional configuration of factors. Although becoming more challenging to Beijing from a trade perspective, he could substantially weaken not only the rules based liberal international order, but the architecture of alliances that contains China. The former, because the illiberal populism that he represents is at odds with the liberal order. The latter, not only because he could take the U.S. out of NATO, but because his transactional approach to foreign policy, which favors trade and money over geopolitics, could turn alliances upside down.

The rules based liberal international order, which became universal over the ashes of the Soviet Union, could now be facing its sunset. This, not only because its main challenger, China, may strengthen its geopolitical position in the face of its rival alliances’ disruption, but, more significantly, because the U.S. itself may cease to champion it.

Feature Image Credit: www.brookings.edu