The Triumphal Arch in Moscow, built in 1829-1834 on Tverskaya Zastava Square to Joseph Bove’s design, commemorates Russia’s victory over Napoleon during the French invasion of Russia in 1812. The arch was dismantled in 1936 as part of Joseph Stalin’s reconstruction of downtown Moscow. The current arch was built to Bove’s original designs in 1966-68 in the middle of Kutuzovsky Avenue (the prospect was named after Marshall Mikhail Kutuzov, who led Russia to victory over Napoleon in 1812. Photo credit: M Matheswaran

My argument is not that Russia has been entirely benign or trustworthy. Rather, it is that Europe has consistently applied double standards in the interpretation of security. While other great powers are presumed to have legitimate security interests that must be balanced and accommodated, Russia’s interests are presumed illegitimate unless proven otherwise.

The lesson, written in blood across two centuries, is not that Russia or any other country must be trusted in all regards. It is that Russia and its security interests must be taken seriously. Europe has repeatedly rejected peace with Russia, not because it was unavailable, but because acknowledging Russia’s security concerns was wrongly treated as illegitimate.

Europe has repeatedly rejected peace with Russia at moments when a negotiated settlement was available, and those rejections have proven profoundly self-defeating. From the nineteenth century to the present, Russia’s security concerns have been treated not as legitimate interests to be negotiated within a broader European order, but as moral transgressions to be resisted, contained, or overridden. This pattern has persisted across radically different Russian regimes—Tsarist, Soviet, and post-Soviet—suggesting that the problem lies not primarily in Russian ideology, but in Europe’s enduring refusal to recognise Russia as a legitimate and equal security actor.

My argument is not that Russia has been entirely benign or trustworthy. Rather, it is that Europe has consistently applied double standards in the interpretation of security. Europe treats its own use of force, alliance-building, and imperial or post-imperial influence as normal and legitimate, while construing comparable Russian behaviour—especially near Russia’s own borders—as inherently destabilising and invalid. This asymmetry has narrowed diplomatic space, delegitimised compromise, and made war more likely. Likewise, this self-defeating cycle remains the defining characteristic of European-Russian relations in the twenty-first century.

A recurring failure throughout this history has been Europe’s inability—or refusal—to distinguish between Russian aggression and Russian security-seeking behaviour. In multiple periods, actions interpreted in Europe as evidence of inherent Russian expansionism were, from Moscow’s perspective, attempts to reduce vulnerability in an environment perceived as increasingly hostile. Meanwhile, Europe consistently interpreted its own alliance building, military deployments, and institutional expansion as benign and defensive, even when these measures directly reduced Russian strategic depth. This asymmetry lies at the heart of the security dilemma that has repeatedly escalated into conflict: one side’s defence is treated as legitimate, while the other side’s fear is dismissed as paranoia or bad faith.

Western Russophobia should not be understood primarily as emotional hostility toward Russians or Russian culture. Instead, it operates as a structural prejudice embedded in European security thinking: the assumption that Russia is the exception to normal diplomatic rules. While other great powers are presumed to have legitimate security interests that must be balanced and accommodated, Russia’s interests are presumed illegitimate unless proven otherwise. This assumption survives changes in regime, ideology, and leadership. It transforms policy disagreements into moral absolutes and renders compromise as suspect. As a result, Russophobia functions less as a sentiment than as a systemic distortion—one that repeatedly undermines Europe’s own security.

The Crimean War emerges as the founding trauma of modern Russophobia: a war of choice pursued by Britain and France despite the availability of diplomatic compromise, driven by the West’s moralised hostility and imperial anxiety rather than unavoidable necessity.

I trace this pattern across four major historical arcs. First, I examine the nineteenth century, beginning with Russia’s central role in the Concert of Europe after 1815 and its subsequent transformation into Europe’s designated menace. The Crimean War emerges as the founding trauma of modern Russophobia: a war of choice pursued by Britain and France despite the availability of diplomatic compromise, driven by the West’s moralised hostility and imperial anxiety rather than unavoidable necessity. The Pogodin memorandum of 1853 on the West’s double standard, featuring Tsar Nicholas I’s famous marginal note—“This is the whole point”—serves not merely as an anecdote, but as an analytical key to Europe’s double standards and Russia’s understandable fears and resentments.

Second, I turn to the revolutionary and interwar periods, when Europe and the United States moved from rivalry with Russia to direct intervention in Russia’s internal affairs. I examine in detail the Western military interventions during the Russian Civil War, the refusal to integrate the Soviet Union into a durable collective-security system in the 1920s and 1930s, and the catastrophic failure to ally against fascism, drawing especially on the archival work of Michael Jabara Carley. The result was not the containment of Soviet power, but the collapse of European security and the devastation of the continent itself in World War II.

Third, the early Cold War presented what should have been a decisive corrective moment; yet, Europe again rejected peace when it could have been secured. Although the Potsdam conference reached an agreement on German demilitarisation, the West subsequently reneged. Seven years later, the West similarly rejected the Stalin Note, which offered German reunification based on neutrality. The dismissal of reunification by Chancellor Adenauer—despite clear evidence that Stalin’s offer was genuine—cemented Germany’s postwar division, entrenched the bloc confrontation, and locked Europe into decades of militarisation.

Europe chose NATO expansion, institutional asymmetry, and a security architecture built around Russia rather than with it. This choice was not accidental. It reflected an Anglo-American grand strategy—articulated most explicitly by Zbigniew Brzezinski—that treated Eurasia as the central arena of global competition and Russia as a power to be prevented from consolidating security or influence.

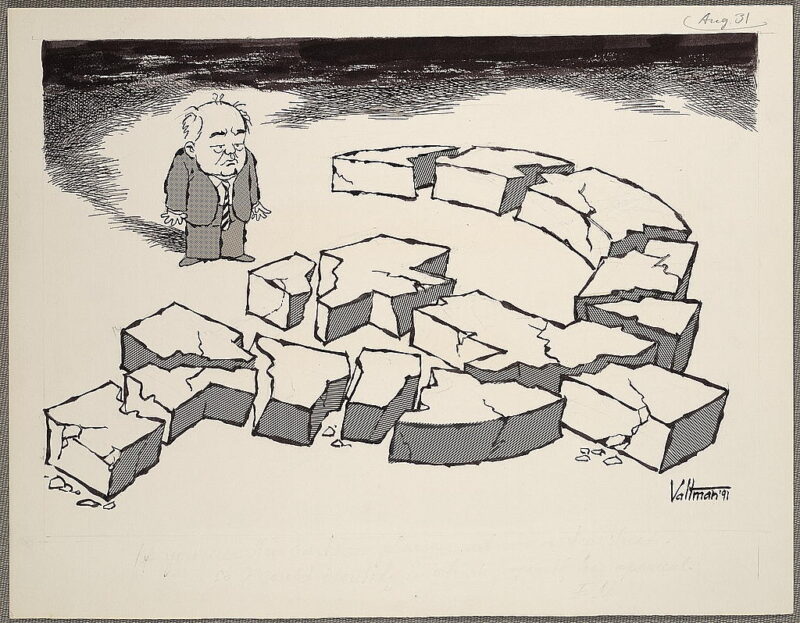

Finally, I analyse the post-Cold War era, when Europe was offered its clearest opportunity to escape this destructive cycle. Gorbachev’s vision of a “Common European Home” and the Charter of Paris articulated a security order based on inclusion and indivisibility. Instead, Europe chose NATO expansion, institutional asymmetry, and a security architecture built around Russia rather than with it. This choice was not accidental. It reflected an Anglo-American grand strategy—articulated most explicitly by Zbigniew Brzezinski—that treated Eurasia as the central arena of global competition and Russia as a power to be prevented from consolidating security or influence.

The consequences of this long pattern of disdain for Russian security concerns are now visible with brutal clarity. The war in Ukraine, the collapse of nuclear arms control, Europe’s energy and industrial shocks, Europe’s new arms race, the EU’s political fragmentation, and Europe’s loss of strategic autonomy are not aberrations. They are the cumulative costs of two centuries of Europe’s refusal to take Russia’s security concerns seriously.

My conclusion is that peace with Russia does not require naïve trust. It requires the recognition that durable European security cannot be built by denying the legitimacy of Russian security interests. Until Europe abandons this reflex, it will remain trapped in a cycle of rejecting peace when it is available—and paying ever higher prices for doing so.

The Origins of Structural Russophobia

The recurrent European failure to build peace with Russia is not primarily a product of Putin, communism, or even twentieth-century ideology. It is much older—and it is structural. Repeatedly, Russia’s security concerns have been treated by Europe not as legitimate interests subject to negotiation, but as moral transgressions. In this sense, the story begins with the nineteenth-century transformation of Russia from a co-guarantor of Europe’s balance into the continent’s designated menace.

After the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, Russia was not peripheral to Europe; it was central. Russia bore a decisive share of the burden in defeating Napoleon, and the Tsar was a principal architect of the post-Napoleonic settlement. The Concert of Europe was built on an implicit proposition: peace requires the great powers to accept one another as legitimate stakeholders and to manage crises by consultation rather than by moralised demonology. Yet, within a generation, a counterproposition gained strength in British and French political culture: that Russia was not a normal great power but a civilizational danger—one whose demands, even when local and defensive, should be treated as inherently expansionist and therefore unacceptable.

That shift is captured with extraordinary clarity in a document highlighted by Orlando Figes in The Crimean War: A History (2010) as being written at the hinge point between diplomacy and war: Mikhail Pogodin’s memorandum to Tsar Nicholas I in 1853. Pogodin lists episodes of Western coercion and imperial violence—far-flung conquests and wars of choice—and contrasts them with Europe’s outrage at Russian actions in adjacent regions:

France takes Algeria from Turkey, and almost every year England annexes another Indian principality: none of this disturbs the balance of power, but when Russia occupies Moldavia and Wallachia, albeit only temporarily, that disturbs the balance of power. France occupies Rome and stays there several years during peacetime: that is nothing; but Russia only thinks of occupying Constantinople, and the peace of Europe is threatened. The English declare war on the Chinese, who have, it seems, offended them: no one has the right to intervene, but Russia is obliged to ask Europe for permission if it quarrels with its neighbour. England threatens Greece to support the false claims of a miserable Jew and burns its fleet: that is a lawful action, but Russia demands a treaty to protect millions of Christians, and that is deemed to strengthen its position in the East at the expense of the balance of power.

Pogodin concludes: “We can expect nothing from the West but blind hatred and malice,” to which Nicholas famously wrote in the margin: “This is the whole point.”

The Pogodin–Nicholas exchange matters because it frames the recurring pathology that returns in every major episode that follows. Europe would repeatedly insist on the universal legitimacy of its own security claims while treating Russia’s security claims as phoney or suspect. This stance creates a particular kind of instability: it makes compromise politically illegitimate in Western capitals, causing diplomacy to collapse not because a bargain is impossible, but because acknowledging Russia’s interests is treated as a moral error.

The Crimean War is the first decisive manifestation of this dynamic. While the proximate crisis involved the Ottoman Empire’s decline and disputes over religious sites, the deeper issue was whether Russia would be allowed to secure a recognised position in the Black Sea–Balkan sphere without being treated as a predator. Modern diplomatic reconstructions emphasise that the Crimean crisis differed from earlier “Eastern crises” because the Concert’s cooperative habits were already eroding, and British opinion had swung toward an extreme anti-Russian posture that narrowed the room for settlement.

What makes the episode so telling is that a negotiated outcome was available. The Vienna Note was intended to reconcile Russian concerns with Ottoman sovereignty and preserve peace. However, it collapsed amid distrust and political incentives for escalation. The Crimean War followed. It was not “necessary” in any strict strategic sense; it was made likely because British and French compromise with Russia had become politically toxic. The consequences were self-defeating for Europe: massive casualties, no durable security architecture, and the entrenchment of an ideological reflex that treated Russia as the exception to normal great-power bargaining. In other words, Europe did not achieve security by rejecting Russia’s security concerns. Rather, it created a longer cycle of hostility that made later crises harder to manage.

The West’s Military Campaign Against Bolshevism

This cycle carried forward into the revolutionary rupture of 1917. When Russia’s regime type changed, the West did not shift from rivalry to neutrality; instead, it moved toward active intervention, treating the existence of a sovereign Russian state outside Western tutelage as intolerable.

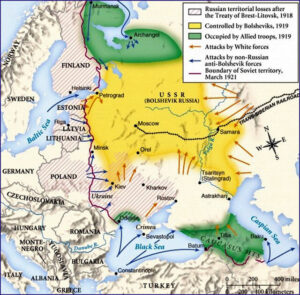

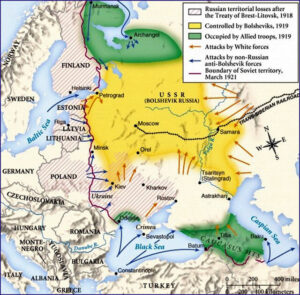

Crucially, the Western powers did not simply “watch” the outcome. They intervened militarily in Russia across vast spaces—North Russia, the Baltic approaches, the Black Sea, Siberia, and the Far East—under justifications that rapidly shifted from wartime logistics to regime change.

The Bolshevik Revolution and the subsequent Civil War produced a complex conflict involving Reds, Whites, nationalist movements, and foreign armies. Crucially, the Western powers did not simply “watch” the outcome. They intervened militarily in Russia across vast spaces—North Russia, the Baltic approaches, the Black Sea, Siberia, and the Far East—under justifications that rapidly shifted from wartime logistics to regime change.

One can acknowledge the standard “official” rationale for initial intervention: the fear that war supplies would fall into German hands after Russia’s exit from World War I, and the desire to reopen an Eastern Front. Yet, once Germany surrendered in November 1918, the intervention did not cease; it mutated. This transformation explains why the episode matters so profoundly: it reveals a willingness, even amidst the devastation of World War I, to use force to shape Russia’s internal political future.

David Foglesong’s America’s Secret War against Bolshevism (1995)—published by UNC Press and still the standard scholarly reference for U.S. policy—captures this precisely. Foglesong frames the U.S. intervention not as a confused sideshow, but as a sustained effort aimed at preventing Bolshevism from consolidating power. Recent high-quality narrative history has further brought this episode back into public view; notably, Anna Reid’s A Nasty Little War (2024) describes the Western intervention as a poorly executed yet deliberate effort to overturn the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

The geographic scope itself is instructive, for it undermines later Western claims that Russia’s fears were mere paranoia. Allied forces landed in Arkhangelsk and Murmansk to operate in North Russia; in Siberia, they entered through Vladivostok and along the rail corridors; Japanese forces deployed on a massive scale in the Far East; and in the south, landings and operations around Odessa and Sevastopol. Even a basic overview of the intervention’s dates and theatres—from November 1917 through the early 1920s—demonstrates the persistence of the foreign presence and the vastness of its range.

the West did not merely oppose Bolshevism; it often did so by aligning with forces whose brutality and war aims sat uneasily with later Western claims to liberal legitimacy.

Nor was this merely “advice” or a symbolic presence. Western forces supplied, armed, and in some instances effectively supervised White formations. The intervening powers became enmeshed in the moral and political ugliness of White politics, including reactionary programs and violent atrocities. This reality renders the episode particularly corrosive to Western moral narratives: the West did not merely oppose Bolshevism; it often did so by aligning with forces whose brutality and war aims sat uneasily with later Western claims to liberal legitimacy.

From Moscow’s perspective, this intervention confirmed the warning issued by Pogodin decades earlier: Europe and the United States were prepared to use force to determine whether Russia would be allowed to exist as an autonomous power. This episode became foundational to Soviet memory, reinforcing the conviction that Western powers had attempted to strangle the revolution in its cradle. It demonstrated that Western moral rhetoric concerning peace and order could seamlessly coexist with coercive campaigns when Russian sovereignty was at stake.

The intervention also produced a decisive second-order consequence. By entering Russia’s civil war, the West inadvertently strengthened Bolshevik legitimacy domestically. The presence of foreign armies and foreign-backed White forces allowed the Bolsheviks to claim they were defending Russian independence against imperial encirclement. Historical accounts consistently note how effectively the Bolsheviks exploited the Allied presence for propaganda and legitimacy. In other words, the attempt to “break” Bolshevism helped consolidate the very regime it sought to destroy

This dynamic reveals the precise cycle of history: Russophobia proves strategically counterproductive for Europe. It drives Western powers toward coercive policies that do not resolve the challenge but exacerbate it. It generates Russian grievances and security fears that later Western leaders will dismiss as irrational paranoia. Furthermore, it narrows future diplomatic space by teaching Russia—regardless of its regime—that Western promises of settlement may be insincere.

By the early 1920s, as foreign forces withdrew and the Soviet state consolidated, Europe had already made two fateful choices that would resonate for the next century. First, it had helped foster a political culture that transformed manageable disputes—like the Crimean crisis—into major wars by refusing to treat Russian interests as legitimate. Second, it demonstrated, through military intervention, a willingness to use force not merely to counter Russian expansion but to shape Russian sovereignty and regime outcomes. These choices did not stabilise Europe; rather, they sowed the seeds for subsequent catastrophes: the interwar breakdown of collective security, the Cold War’s permanent militarisation, and the post-Cold War order’s return to frontier escalation.

Collective Security and the Choice Against Russia

By the mid-1920s, Europe confronted a Russia that had survived every attempt—revolution, civil war, famine, and direct foreign military intervention—to destroy it. The Soviet state that emerged was poor, traumatised, and deeply suspicious—but also unmistakably sovereign. At precisely this moment, Europe faced a choice that would recur repeatedly: whether to treat this Russia as a legitimate security actor whose interests had to be incorporated into European order, or as a permanent outsider whose concerns could be ignored, deferred, or overridden. Europe chose the latter, and the costs proved enormous.

The legacy of the Allied interventions during the Russian Civil War cast a long shadow over all subsequent diplomacy. From Moscow’s perspective, Europe had not merely disagreed with Bolshevik ideology; it had attempted to decide Russia’s internal political future by force. This experience mattered profoundly. It shaped Soviet assumptions about Western intentions and created a deep skepticism toward Western assurances. Rather than recognising this history and seeking reconciliation, European diplomacy often behaved as if Soviet mistrust were irrational—a pattern that would persist into the Cold War and beyond.

Throughout the 1920s, Europe oscillated between tactical engagement and strategic exclusion. Treaties such as Rapallo (1922) demonstrated that Germany, itself a pariah after Versailles, could pragmatically engage with Soviet Russia. Yet for Britain and France, engagement with Moscow remained provisional and instrumental. The USSR was tolerated when it served British and French interests and sidelined when it did not. No serious effort was made to integrate Russia into a durable European security architecture as an equal.

This ambivalence hardened into something far more dangerous and self-destructive in the 1930s. While the rise of Hitler posed an existential threat to Europe, the continent’s leading powers repeatedly treated Bolshevism as the greater danger. This was not merely rhetorical; it shaped concrete policy choices—alliances foregone, guarantees delayed, and deterrence undermined.

France, Britain, and Poland repeatedly made strategic choices that excluded the Soviet Union from European security arrangements, even when Soviet participation would have strengthened deterrence against Hitler’s Germany.

It is essential to underscore that this was not merely an Anglo-American failure, nor a story in which Europe was passively swept along by ideological currents. European governments exercised agency, and they did so decisively—and disastrously. France, Britain, and Poland repeatedly made strategic choices that excluded the Soviet Union from European security arrangements, even when Soviet participation would have strengthened deterrence against Hitler’s Germany. French leaders preferred a system of bilateral guarantees in Eastern Europe that preserved French influence but avoided security integration with Moscow. Poland, with the tacit backing of London and Paris, refused transit rights to Soviet forces even to defend Czechoslovakia, prioritising its fear of Soviet presence over the imminent danger of German aggression. These were not small decisions. They reflected a European preference for managing Hitlerian revisionism over incorporating Soviet power, and for risking Nazi expansion rather than legitimising Russia as a security partner. In this sense, Europe did not merely fail to build collective security with Russia; it actively chose an alternative security logic that excluded Russia and ultimately collapsed under its own contradictions.

Here, Michael Jabara Carley’s archival work is decisive. His scholarship demonstrates that the Soviet Union, particularly under Foreign Commissar Maxim Litvinov, made sustained, explicit, and well-documented efforts to build a system of collective security against Nazi Germany. These were not vague gestures. They included proposals for mutual assistance treaties, military coordination, and explicit guarantees for states such as Czechoslovakia. Carley shows that Soviet entry into the League of Nations in 1934 was accompanied by genuine Russian attempts to operationalise collective deterrence, not simply to seek legitimacy.

However, these efforts collided with a Western ideological hierarchy in which anti-communism trumped anti-fascism. In London and Paris, political elites feared that an alliance with Moscow would legitimise Bolshevism domestically and internationally. As Carley documents, British and French policymakers repeatedly worried less about Hitler’s threats than about the political consequences of cooperation with the USSR. The Soviet Union was treated not as a necessary partner against a common threat, but as a liability whose inclusion would “contaminate” European politics.

This hierarchy had profound strategic consequences. The policy of appeasement toward Germany was not merely a misreading of Hitler; it was the product of a worldview that treated Nazi revisionism as potentially manageable, while treating Soviet power as inherently subversive. Poland’s refusal to allow Soviet troops transit rights to defend Czechoslovakia—maintained with tacit Western support—is emblematic. European states preferred the risk of German aggression to the certainty of Soviet involvement, even when Soviet involvement was explicitly defensive.

The Anglo-French negotiations with the Soviet Union in Moscow were not sabotaged by Soviet duplicity, contrary to later mythology. They failed because Britain and France were unwilling to make binding commitments or to recognise the USSR as an equal military partner.

The culmination of this failure came in 1939. The Anglo-French negotiations with the Soviet Union in Moscow were not sabotaged by Soviet duplicity, contrary to later mythology. They failed because Britain and France were unwilling to make binding commitments or to recognise the USSR as an equal military partner. Carley’s reconstruction shows that the Western delegations to Moscow arrived without negotiating authority, without urgency, and without political backing to conclude a real alliance. When the Soviets repeatedly asked the essential question of any alliance—Are you prepared to act?—the answer, in practice, was no.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact that followed has been used ever since as retroactive justification for Western distrust. Carley’s work reverses that logic. The pact was not the cause of Europe’s failure; it was the consequence. It emerged after years of the West’s refusal to build collective security with Russia. It was a brutal, cynical, and tragic decision—but one taken in a context where Britain, France, and Poland had already rejected peace with Russia in the only form that might have stopped Hitler.

The result was catastrophic. Europe paid the price not only in blood and destruction but in the loss of agency. The war that Europe failed to prevent destroyed its power, exhausted its societies, and reduced the continent to the primary battlefield of superpower rivalry. Once again, rejecting peace with Russia did not produce security; it produced a far worse war under far worse conditions.

One might have expected that the sheer scale of this disaster would have forced a rethinking of Europe’s approach to Russia after 1945. It did not.

From Potsdam to NATO: The Architecture of Exclusion

The immediate postwar years were marked by a rapid transition from alliance to confrontation. Even before Germany surrendered, Churchill shockingly instructed British war planners to consider an immediate conflict with the Soviet Union. “Operation Unthinkable,” drafted in 1945, envisioned using Anglo-American power—and even rearmed German units—to impose Western will on Russia in 1945 or soon after. While the plan was deemed to be militarily unrealistic and was ultimately shelved, its very existence reveals how deeply ingrained the assumption had become that Russian power was illegitimate and must be constrained by force if necessary.

Western diplomacy with the Soviet Union similarly failed. Europe should have recognised that the Soviet Union had borne the brunt of defeating Hitler—suffering 27 million casualties—and that Russia’s security concerns regarding German rearmament were entirely real. Europe should have internalised the lesson that a durable peace required the explicit accommodation of Russia’s core security concerns, above all, the prevention of a remilitarized Germany that could once again threaten the eastern plains of Europe.

In formal diplomatic terms, that lesson was initially accepted. At Yalta and, more decisively, at Potsdam in the summer of 1945, the victorious Allies reached a clear consensus on the basic principles governing postwar Germany: demilitarisation, denazification, democratisation, decartelization, and reparations. Germany was to be treated as a single economic unit; its armed forces were to be dismantled; and its future political orientation was to be determined without rearmament or alliance commitments.

For the Soviet Union, these principles were not abstract; they were existential. Twice within thirty years, Germany had invaded Russia, inflicting devastation on a scale without parallel in European history. Soviet losses in World War II gave Moscow a security perspective that cannot be understood without acknowledging that trauma. Neutrality and permanent demilitarisation of Germany were not bargaining chips; they were the minimum conditions for a stable postwar order from the Soviet point of view.

At the Potsdam Conference in July 1945, these concerns were formally recognised. The Allies agreed that Germany would not be allowed to reconstitute military power. The language of the conference was explicit: Germany was to be prevented from “ever again threatening its neighbours or the peace of the world.” The Soviet Union accepted the temporary division of Germany into occupation zones precisely because this division was framed as an administrative necessity, not a permanent geopolitical settlement.

Yet almost immediately, the Western powers began to reinterpret—and then quietly dismantle—these commitments. The shift occurred because U.S. and British strategic priorities changed. As Melvyn Leffler demonstrates in A Preponderance of Power (1992), American planners rapidly came to view German economic recovery and political alignment with the West as more important than maintaining a demilitarised Germany acceptable to Moscow. The Soviet Union, once an indispensable ally, was recast as a potential adversary whose influence in Europe needed to be contained.

This reorientation preceded any formal Cold War military crisis. Long before the Berlin Blockade, Western policy began to consolidate the Western zones economically and politically. The creation of the Bizone in 1947, followed by the Trizone, directly contradicted the Potsdam principle that Germany would be treated as a single economic unit. The introduction of a separate currency in the western zones in 1948 was not a technical adjustment; it was a decisive political act that made German division functionally irreversible. From Moscow’s perspective, these steps were unilateral revisions of the postwar settlement.

The Soviet response—the Berlin Blockade—has often been portrayed as the opening salvo of Cold War aggression. Yet, in context, it appears less as an attempt to seize Western Berlin than as a coercive effort to force a return to four-power governance and prevent the consolidation of a separate West German state. Regardless of whether one judges the blockade wisely, its logic was rooted in the fear that the Potsdam framework was being dismantled by the West without negotiation. While the airlift resolved the immediate crisis, it did not address the underlying issue: the abandonment of a unified, demilitarised Germany.

The decisive break came with the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950. The conflict was interpreted in Washington not as a regional war with specific causes, but as evidence of a monolithic global communist offensive. This reductionist interpretation had profound consequences for Europe. It provided the strong political justification for West German rearmament—something that had been explicitly ruled out only a few years earlier. The logic was now framed in stark terms: without German military participation, Western Europe could not be defended.

The remilitarization of West Germany was not forced by Soviet action in Europe; it was a strategic choice made by the United States and its allies in response to a globalised Cold War framework the U.S. had constructed. Britain and France, despite deep historical anxieties about German power, acquiesced under American pressure.

This moment was a watershed. The remilitarization of West Germany was not forced by Soviet action in Europe; it was a strategic choice made by the United States and its allies in response to a globalised Cold War framework the U.S. had constructed. Britain and France, despite deep historical anxieties about German power, acquiesced under American pressure. When the proposed European Defence Community—a means of controlling German rearmament—collapsed, the solution adopted was even more consequential: West Germany’s accession to NATO in 1955.

From the Soviet perspective, this represented the definitive collapse of the Potsdam settlement. Germany was no longer neutral. It was no longer demilitarised. It was now embedded in a military alliance explicitly oriented against the USSR. This was precisely the outcome that Soviet leaders had sought to prevent since 1945, and which the Potsdam Agreement had been designed to forestall.

It is essential to underline the sequence, as it is often misunderstood or inverted. The division and remilitarization of Germany were not the result of Russian actions. By the time Stalin made his 1952 offer of German reunification based on neutrality, the Western powers had already set Germany on a path toward alliance integration and rearmament. The Stalin Note was not an attempt to derail a neutral Germany; it was a serious, documented, and ultimately rejected attempt to reverse a process already underway.

Seen in this light, the early Cold War settlement appears not as an inevitable response to Soviet intransigence, but as another instance in which Europe and the U.S. chose to subordinate Russian security concerns to the NATO alliance architecture. Germany’s neutrality was not rejected because it was unworkable; it was rejected because it conflicted with a Western strategic vision that prioritised bloc cohesion and U.S. leadership over an inclusive European security order.

The costs of this choice were immense and enduring. Germany’s division became the central fault line of the Cold War. Europe was permanently militarised, and nuclear weapons were deployed across the continent. European security was externalised to Washington, with all the dependency and loss of strategic autonomy that entailed. Furthermore, the Soviet conviction that the West would reinterpret agreements when convenient was reinforced once again.

This context is indispensable for understanding the Stalin Note in 1952. It was not a “bolt from the blue,” nor a cynical manoeuvre detached from prior history. It was an urgent response to a postwar settlement that had already been broken—another attempt, like so many before and after, to secure peace through neutrality, only to see that offer rejected by the West.

1952: The Rejection of German Reunification

It is worth examining the Stalin Note in greater detail. Stalin’s call for a reunified and neutral Germany was neither ambiguous, tentative, nor insincere. As Rolf Steininger has demonstrated conclusively in The German Question: The Stalin Note of 1952 and the Problem of Reunification (1990), Stalin proposed German reunification under conditions of permanent neutrality, free elections, the withdrawal of occupation forces, and a peace treaty guaranteed by the great powers. This was not a propaganda gesture; it was a strategic offer rooted in a genuine Soviet fear of German rearmament and NATO expansion.

Steininger’s archival research is devastating to the standard Western narrative. Particularly decisive is the 1955 secret memorandum by Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick, in which he reports the German ambassador’s admission that Chancellor Adenauer knew the Stalin Note was genuine. Adenauer rejected it regardless. He feared not Soviet bad faith, but German democracy. He worried that a future German government might choose neutrality and reconciliation with Moscow, undermining West Germany’s integration into the Western bloc.

In essence, peace and reunification were rejected by the West not because they were impossible, but because they were politically inconvenient for the Western alliance system. Because neutrality threatened NATO’s emerging architecture, it had to be dismissed as a “trap.”

Chancellor Adenauer’s rejection of German neutrality was not an isolated act of deference to Washington but reflected a broader consensus among West European elites who preferred American tutelage to strategic autonomy and a unified Europe. Neutrality threatened not only NATO’s architecture but also the postwar political order in which these elites derived security, legitimacy, and economic reconstruction through U.S. leadership.

European elites were not merely coerced into Atlantic alignment; they actively embraced it. Chancellor Adenauer’s rejection of German neutrality was not an isolated act of deference to Washington but reflected a broader consensus among West European elites who preferred American tutelage to strategic autonomy and a unified Europe. Neutrality threatened not only NATO’s architecture but also the postwar political order in which these elites derived security, legitimacy, and economic reconstruction through U.S. leadership. A neutral Germany would have required European states to negotiate directly with Moscow as equals, rather than operating within a U.S.-led framework that insulated them from such engagement. In this sense, Europe’s rejection of neutrality was also a rejection of responsibility: Atlanticism offered security without the burdens of diplomatic coexistence with Russia, even at the price of Europe’s permanent division and militarisation of the continent.

In March 1954, the Soviet Union applied to join NATO, arguing that NATO would thereby become an institution for European collective security. The US and its allies immediately rejected the application on the grounds that it would dilute the alliance and forestall Germany’s accession to NATO. The US and its allies, including West Germany itself, once again rejected the idea of a neutral, demilitarised Germany and a European security system built on collective security rather than military blocs.

The Austrian State Treaty of 1955 further exposed the cynicism of this logic. Austria accepted neutrality, Soviet troops withdrew, and the country became stable and prosperous. The predicted geopolitical “dominoes” did not fall. The Austrian model demonstrates that what was achieved there could have been achieved in Germany, potentially ending the Cold War decades earlier. The distinction between Austria and Germany lay not in feasibility, but in strategic preference. Europe accepted neutrality in Austria, where it did not threaten the U.S.-led hegemonic order, but rejected it in Germany, where it did.

The consequences of these decisions were immense and enduring. Germany remained divided for nearly four decades. The continent was militarised along a fault line running through its centre, and nuclear weapons were deployed across European soil. European security became dependent on American power and American strategic priorities, rendering the continent, once again, the primary arena of great-power confrontation.

By 1955, the pattern was firmly established. Europe would accept peace with Russia only when it aligned seamlessly with the U.S.-led, Western strategic architecture. When peace required genuine accommodation of Russian security interests—German neutrality, non-alignment, demilitarisation, or shared guarantees—it was systematically rejected. The consequences of this refusal would unfold over the ensuing decades.

The 30-Year Refusal of Russian Security Concerns

If there was ever a moment when Europe could have broken decisively with its long tradition of rejecting peace with Russia, it was the end of the Cold War. Unlike 1815,1919, or 1945, this was not a moment imposed by military defeat alone; it was a moment shaped by choice. The Soviet Union did not collapse in a hail of artillery fire; it withdrew and unilaterally disarmed. Under Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union renounced force as an organising principle of European order. Both the Soviet Union and, subsequently, Russia under Boris Yeltsin accepted the loss of military control over Central and Eastern Europe and proposed a new security framework based on inclusion rather than competing blocs. What followed was not a failure of Russian imagination, but a failure of Europe and the U.S.-led Atlantic system to take that offer seriously.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s concept of a “Common European Home” was not a mere rhetorical flourish. It was a strategic doctrine grounded in the recognition that nuclear weapons had rendered traditional balance-of-power politics suicidal. Gorbachev envisioned a Europe in which security was indivisible, where no state enhanced its security at the expense of another, and where Cold War alliance structures would gradually yield to a pan-European framework. His 1989 address to the Council of Europe in Strasbourg made this vision explicit, emphasising cooperation, mutual security guarantees, and the abandonment of force as a political instrument. The Charter of Paris for a New Europe, signed in November 1990, codified these principles, committing Europe to democracy, human rights, and a new era of cooperative security.

At this juncture, Europe faced a fundamental choice. It could have treated these commitments seriously and built a security architecture centred on the OSCE, in which Russia was a co-equal participant—a guarantor of peace rather than an object of containment. Alternatively, it could preserve the Cold War institutional hierarchy while rhetorically embracing post-Cold War ideals. Europe chose the latter.

NATO did not dissolve, transform itself into a political forum, or subordinate itself to a pan-European security institution. On the contrary, it expanded. The rationale offered publicly was defensive: NATO enlargement would stabilise Eastern Europe, consolidate democracy, and prevent a security vacuum. Yet, this explanation ignored a crucial fact that Russia repeatedly articulated and that Western policymakers privately acknowledged: NATO expansion directly implicated Russia’s core security concerns—not abstractly, but geographically, historically, and psychologically.

Declassified documents and contemporaneous accounts confirm that Soviet leaders were repeatedly told that NATO would not move eastward beyond Germany. These assurances shaped Soviet acquiescence to German reunification—a concession of immense strategic significance. When NATO expanded regardless, initially at America’s behest, Russia experienced this not as a technical legal adjustment, but as a deep betrayal of the settlement that had facilitated German reunification.

The controversy over assurances given by the U.S. and Germany during German reunification negotiations illustrates the deeper issue. Western leaders later insisted that no legally binding promises had been made regarding NATO expansion because no agreement was codified in writing. However, diplomacy operates not only through signed treaties but through expectations, understandings, and good faith. Declassified documents and contemporaneous accounts confirm that Soviet leaders were repeatedly told that NATO would not move eastward beyond Germany. These assurances shaped Soviet acquiescence to German reunification—a concession of immense strategic significance. When NATO expanded regardless, initially at America’s behest, Russia experienced this not as a technical legal adjustment, but as a deep betrayal of the settlement that had facilitated German reunification.

Over time, European governments increasingly internalised NATO expansion as a European project, not merely an American one. German reunification within NATO became the template rather than the exception. EU enlargement and NATO enlargement proceeded in tandem, reinforcing one another and crowding out alternative security arrangements such as neutrality or non-alignment. Even Germany, with its Ostpolitik tradition and deepening economic ties to Russia, progressively subordinated its policies, favouring accommodation to alliance logic. European leaders framed expansion as a moral imperative rather than a strategic choice, thereby insulating it from scrutiny and rendering Russian objections illegitimate. In doing so, Europe surrendered much of its capacity to act as an independent security actor, tying its fate ever more tightly to an Atlantic strategy that privileged expansion over stability.

This is where Europe’s failure becomes most stark. Rather than acknowledging that NATO expansion contradicted the logic of indivisible security articulated in the Charter of Paris, European leaders treated Russian objections as illegitimate—as residues of imperial nostalgia rather than expressions of genuine security anxiety. Russia was invited to consult, but not to decide. The 1997 NATO–Russia Founding Act institutionalised this asymmetry: dialogue without a Russian veto, partnership without Russian parity. The architecture of European security was being built around Russia, and despite Russia, not with Russia.

George Kennan’s 1997 warning that NATO expansion would be a “fateful error” captured the strategic risk with remarkable clarity. Kennan did not argue that Russia was virtuous; he argued that humiliating and marginalising a great power at a moment of weakness would produce resentment, revanchism, and militarisation. His warning was dismissed as outdated realism, yet subsequent history has vindicated his logic almost point by point.

The ideological underpinning of this dismissal can be found explicitly in the writings of Zbigniew Brzezinski. In The Grand Chessboard (1997) and in his Foreign Affairs essay “A Geostrategy for Eurasia” (1997), Brzezinski articulated a vision of American primacy grounded in control over Eurasia. He argued that Eurasia was the “axial supercontinent,” and U.S. global dominance depended on preventing the emergence of any power capable of dominating it. In this framework, Ukraine was not merely a sovereign state with its own trajectory; it was a geopolitical pivot. “Without Ukraine,” Brzezinski famously wrote, “Russia ceases to be an empire.”

This was not an academic aside; it was a programmatic statement of U.S. imperial grand strategy. In such a worldview, Russia’s security concerns are not legitimate interests to be accommodated in the name of peace; they are obstacles to be overcome in the name of U.S. primacy. Europe, deeply embedded in the Atlantic system and dependent on U.S. security guarantees, internalised this logic—often without acknowledging its full implications. The result was a European security policy that consistently privileged alliance expansion over stability, and moral signalling over durable settlement.

The consequences became unmistakable in 2008. At NATO’s Bucharest Summit, the alliance declared that Ukraine and Georgia “will become members of NATO.” This statement was not accompanied by a clear timeline, but its political meaning was unequivocal. It crossed what Russian officials across the political spectrum had long described as a red line. That this was understood in advance is beyond dispute. William Burns, then U.S. ambassador to Moscow, reported in a cable titled “NYET MEANS NYET” that Ukrainian NATO membership was perceived in Russia as an existential threat, uniting liberals, nationalists, and hardliners alike. The warning was explicit. It was ignored.

From Russia’s perspective, the pattern was now unmistakable. Europe and the United States invoked the language of rules and sovereignty when it suited them, but dismissed Russia’s core security concerns as illegitimate. The lesson Russia drew was the same lesson it had drawn after the Crimean War, after the Allied interventions, after the failure of collective security, and after the rejection of the Stalin Note: peace would be offered only on terms that preserved Western strategic dominance.

The crisis that erupted in Ukraine in 2014 was therefore not an aberration but a culmination. The Maidan uprising, the collapse of the Yanukovych government, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and the war in Donbas unfolded within a security architecture already strained to the breaking point. The U.S. actively encouraged the coup that overthrew Yanukovych, even plotting in the background regarding the composition of the new government. When the Donbas region erupted in opposition to the Maidan coup, Europe responded with sanctions and diplomatic condemnation, framing the conflict as a simple morality play. Yet even at this stage, a negotiated settlement was possible. The Minsk agreements, particularly Minsk II in 2015, provided a framework for de-escalation of the conflict, autonomy for the Donbas, and reintegration of Ukraine and Russia within an expanded European economic order.

When Western leaders later suggested that Minsk II had functioned primarily to “buy time” for Ukraine to strengthen militarily, the strategic damage was severe. From Moscow’s perspective, this confirmed the suspicion that Western diplomacy was cynical and instrumental rather than sincere—that agreements were not meant to be implemented, only to manage optics.

Minsk II represented an acknowledgement—however reluctant—that peace required compromise and that Ukraine’s stability depended on addressing both internal divisions and external security concerns. What ultimately destroyed Minsk II was Western resistance. When Western leaders later suggested that Minsk II had functioned primarily to “buy time” for Ukraine to strengthen militarily, the strategic damage was severe. From Moscow’s perspective, this confirmed the suspicion that Western diplomacy was cynical and instrumental rather than sincere—that agreements were not meant to be implemented, only to manage optics.

By 2021, the European security architecture had become untenable. Russia presented draft proposals calling for negotiations over NATO expansion, missile deployments, and military exercises—precisely the issues it had warned about for decades. These proposals were dismissed by the U.S. and NATO out of hand. NATO expansion was declared non-negotiable. Once again, Europe and the United States refused to engage Russia’s core security concerns as legitimate subjects of negotiation. War followed.

When Russian forces entered Ukraine in February 2022, Europe described the invasion as “unprovoked.” While this absurd description may serve a propaganda narrative, it utterly obscures history. The Russian action hardly emerged from a vacuum. It emerged from a security order that had systematically refused to integrate Russia’s concerns and from a diplomatic process that had ruled out negotiation on the very issues that mattered most to Russia.

Even then, peace was not impossible. In March and April 2022, Russia and Ukraine engaged in negotiations in Istanbul that produced a detailed draft framework. Ukraine proposed permanent neutrality with international security guarantees; Russia accepted the principle. The framework addressed force limitations, guarantees, and a longer process for territorial questions. These were not fantasy documents. They were serious drafts reflecting the realities of the battlefield and the structural constraints of geography.

Yet the Istanbul talks collapsed when the U.S. and U.K. stepped in and told Ukraine not to sign. As Boris Johnson later explained, nothing less than Western hegemony was on the line. The collapsed Istanbul Process demonstrates concretely that peace in Ukraine was possible soon after the start of Russia’s special military operation. The agreement was drafted and nearly completed, only to be abandoned at the behest of the U.S. and the U.K.

By 2025, the grim irony became clear. The same Istanbul framework resurfaced as a reference point in renewed diplomatic efforts. After immense bloodshed, diplomacy circled back to a plausible compromise. This is a familiar pattern in wars shaped by security dilemmas: early settlements that are rejected as premature later reappear as tragic necessities. Yet even now, Europe resists a negotiated peace.

For Europe, the costs of this long refusal to take Russia’s security concerns seriously are now unavoidable and massive. Europe has borne severe economic losses from energy disruption and de-industrialisation pressures. It has committed itself to long-term rearmament with profound fiscal, social, and political consequences. Political cohesion within European societies is badly frayed under the strain of inflation, migration pressures, war fatigue, and diverging viewpoints across European governments. Europe’s strategic autonomy has diminished as Europe once again becomes the primary theatre of great-power confrontation rather than an independent pole.

Perhaps most dangerously, nuclear risk has returned to the centre of European security calculations. For the first time since the Cold War, European publics are once again living under the shadow of potential escalation between nuclear-armed powers. This is not the result of moral failure alone. It is the result of the West’s structural refusal, stretching back to Pogodin’s time, to recognise that peace in Europe cannot be built by denying Russia’s security concerns. Peace can only be built by negotiating them.

The tragedy of Europe’s denial of Russia’s security concerns is that it becomes self-reinforcing. When Russian security concerns are dismissed as illegitimate, Russian leaders have fewer incentives to pursue diplomacy and greater incentives to change facts on the ground. European policymakers then interpret these actions as confirmation of their original suspicions, rather than as the utterly predictable outcome of a security dilemma they themselves created and then denied. Over time, this dynamic narrows the diplomatic space until war appears to many not as a choice but as an inevitability. Yet the inevitability is manufactured. It arises not from immutable hostility but from the persistent European refusal to recognise that durable peace requires acknowledging the other side’s fears as real, even when those fears are inconvenient.

The tragedy is that Europe has repeatedly paid heavily for this refusal. It paid in the Crimean War and its aftermath, in the catastrophes of the first half of the twentieth century, and in decades of Cold War division. And it is paying again now. Russophobia has not made Europe safer. It has made Europe poorer, more divided, more militarised, and more dependent on external power.

By refusing to treat Russia as a normal security actor, Europe has helped generate the very instability it fears, while incurring mounting costs in blood, treasure, autonomy, and cohesion.

The added irony is that while this structural Russophobia has not weakened Russia in the long run, it has repeatedly weakened Europe. By refusing to treat Russia as a normal security actor, Europe has helped generate the very instability it fears, while incurring mounting costs in blood, treasure, autonomy, and cohesion. Each cycle ends the same way: a belated recognition that peace requires negotiation after immense damage has already been done. The lesson Europe has yet to absorb is that recognising Russia’s security concerns is not a concession to power, but a prerequisite for preventing its destructive uses.

The lesson, written in blood across two centuries, is not that Russia or any other country must be trusted in all regards. It is that Russia and its security interests must be taken seriously. Europe has repeatedly rejected peace with Russia, not because it was unavailable, but because acknowledging Russia’s security concerns was wrongly treated as illegitimate. Until Europe abandons that reflex, it will remain trapped in a cycle of self-defeating confrontation—rejecting peace when it is possible and bearing the costs long after.

This article was published earlier at www.cirsd.org