Introduction

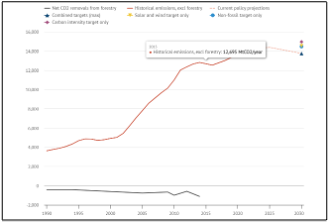

The devastating role carbon plays in climate change cannot be underestimated. The rise in global surface temperatures, air pollution, and sea levels are visible effects of a rapidly changing environment. China, the world’s second most populous country, is also the largest emitter of greenhouse gases[i]. According to the CAIT database, in 2020, China emitted what amounted to 27% of the total greenhouse gas emissions in the world[ii]. Under President Xi Jinping, China has moved to position itself as an “ecological civilization”, striving to advance its role in global climate protection[iii]. China’s endeavours received acclaim when it became one of the first major countries to ratify the Paris Agreement in 2015, pledging to attain peak emissions by 2030 and net zero carbon emissions by 2060. This article aims to delineate China’s strategies and motivations for addressing carbon emissions and contrast these with the measures implemented by Western and developing countries to diminish their carbon footprint.

China’s Image and Geopolitics in the Climate Sector

Considering China’s position on the world stage as one of the largest and fastest-growing economies in the world, it has faced international pressure to take accountability for its contribution to climate change. China has previously argued that as a developing country, it should not have to share the same responsibilities of curbing climate change that developed countries, whose emissions went “unchecked for decades”, have[iv]. Nonetheless, they have pledged to lead by example in the climate sector. A large part of President Xi’s campaign to amplify China’s climate ambitions may come from appeasing the West while also setting up leadership in the clean energy sector to better cement its role as a superpower. According to a New York Times article, their promise to contribute to climate protection could be used to soothe the international audience and to counterbalance the worldwide anger that China faces over their oppression of the Uyghur Muslims in the Xinjiang province and their territorial conflicts in the South China Sea and Taiwan[v]. President Xi’s pledge at the UN to reach peak emissions before 2030 may have been an attempt to depict China as a pioneering nation striving to achieve net zero carbon emissions, serving as an alternative powerful entity for countries to turn to in lieu of the United States. This holds particular significance, as the USA remained mute about taking accountability for its own carbon emissions and withdrew from the Paris Agreement during Donald Trump’s presidency[vi]. This also shows China’s readiness to employ the consequences of climate change on its geopolitical agenda[vii].

The future actions of China may significantly influence the climate policies of both developing and developed nations, potentially establishing China as a preeminent global force in climate change mitigation.

China has endeavoured to shape its image in the climate sector. In 2015, despite being classified as a developing country, China refrained from requesting climate finance from developed countries and instead pledged $ 3.1 billion in funding to assist other developing countries in tackling climate change[viii]. As per the World Bank’s Country Climate and Development Report for China, China is poised to transform “climate action into economic opportunity.”[ix] By transitioning to a net zero carbon emissions economy, China can generate employment opportunities while safeguarding its non-renewable resources from depletion. China’s economy is also uniquely structured to seize the technological and reputational benefits of early climate action[x]. The future actions of China may significantly influence the climate policies of both developing and developed nations, potentially establishing China as a preeminent global force in climate change mitigation. Nonetheless, if China fails to fulfil its commitment to attain net zero carbon emissions by 2060, it may suffer substantial reputational damage, particularly given its current status as a pioneer in “advancing low carbon energy supply”[xi].

Domestic Versus International Efforts in the Clean Energy Race

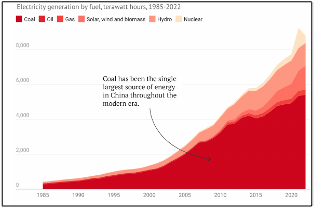

However, domestic and international factors could affect China’s goal to peak emissions and the deadlines it has set for itself. A global event that may have affected their efforts to peak carbon emissions was the COVID-19 pandemic, in which the rise in carbon emissions from industries and vehicles was interrupted[xii]. However, after the pandemic, China’s economy saw swift growth, and in 2021, China’s carbon emissions were 4% higher than in the previous year[xiii]. Not only is China back on track to peak carbon emissions by 2030, but the International Energy Agency and World Energy Outlook 2023 also found that “China’s fossil fuel use will peak in 2024 before entering structural decline.”[xiv]

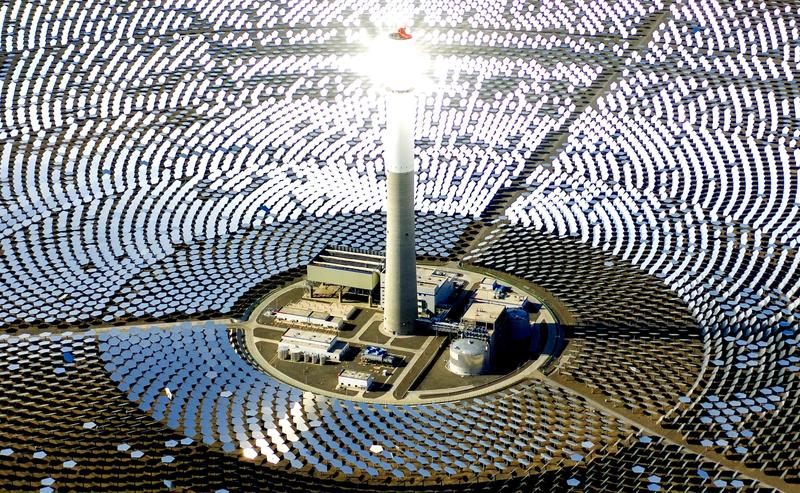

Although China’s industrial sector is heavily reliant on coal and fossil fuels, it also boasts the world’s largest production of electric vehicles and is a leader in manufacturing solar panels and wind turbines[xv]. In contrast, developed countries, particularly the US, which withdrew from the Paris Agreement in 2017 during the Trump presidency, appear to be making less of an effort towards environmental protection.

Developing countries, while not entirely possessed of the immense sprawl of China’s economy and population, are nonetheless not at the level of transitioning to clean energy that China is. India, too, has pledged to be carbon neutral by 2070 and to have emissions peak by 2030. Given its increasing economic growth rate, India must decrease its carbon intensity at the same pace. India lags behind China when it comes to manufacturing solar panels and other renewable energy sources. India’s central government is preparing to push energy modernization to “align with global energy transition trends.”[xvi] According to the Economic Times, particular emphasis has been laid on renewable energy sources like solar capacity and e-vehicles in the 2024-25 budget.[xvii]

China and International Cooperation for Climate Protection

With China producing sufficient solar capacity in 2022 to lead the rest of the world considerably and the deployment of solar power expected to rise until 2028, it is essential that the West does not make the mistake of isolating China

Given that China has emerged as the leading manufacturer of electric vehicles (EVs), it remains to be seen whether developed and developing countries will leverage their supply chains to combat their own climate crises. While opportunities are plentiful for Western businesses to integrate with China’s cutting-edge alternatives for traditional energy sources, the United States has adopted a hardline stance towards China[xviii]. The US has imposed 100 per cent tariffs on Chinese-made e-vehicles, and solar cells face tariffs at 50 per cent.[xix] Simultaneously, rivalry and competition between the two countries on the climate front may help combat the climate dilemma and ever-increasing carbon emissions by avoiding the collective action problem. However, this will depend heavily on smooth cooperation and effective communication between Chinese authorities and developed nations within the EU and the USA[xxi]. Empowering domestic groups within countries can raise awareness of climate crises. A poll conducted in China revealed that 46% of the youth considered climate change the “most serious global issue.”[xxii] According to a survey conducted by the United Nations, 80% of people worldwide say they want climate action[vii]. With China producing sufficient solar capacity in 2022 to lead the rest of the world considerably and the deployment of solar power expected to rise until 2028, it is essential that the West does not make the mistake of isolating China[xxiii].

Conclusion

China has a significant advantage in its renewable energy sector. Western countries and other developing economies rely heavily on China’s green exports to address climate change urgently. China’s stringent measures to curb emissions from its coal-based industries and the growing output from its alternative energy sources reflect its proactive stance in becoming a global leader in addressing climate change — a position that surpasses other nations’ efforts. While it is debatable whether China’s commitment to reduce its carbon emissions was a political strategy to appease Europe, it is undeniable that tackling climate change is a pressing issue. With the public’s overwhelming support for implementing change in the climate sector, governments worldwide must prioritise their citizens’ needs and cooperate to develop policies that ensure a sustainable future for our planet.

Notes:

[i] Saurav Anand, “Solar Capacity, EVs, and Nuclear SMRs to Get Budget Boost for Energy Security – ET EnergyWorld,” ETEnergyworld.com, July 11, 2024, https://energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/renewable/solar-capacity-evs-and-nuclear-smrs-to-get-budget-boost-for-energy-security/111648384?action=profile_completion&utm_source=Mailer&utm_medium=newsletter&utm_campaign=etenergy_news_2024-07-11&dt=2024-07-11&em=c2FuYS5zYXByYTIyMUBnbWFpbC5jb20.

[ii]Saurav Anand, “Solar Capacity, EVs, and Nuclear Smrs to Get Budget Boost for Energy Security – ET EnergyWorld,” ETEnergyworld.com, July 11, 2024, https://energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/renewable/solar-capacity-evs-and-nuclear-smrs-to-get-budget-boost-for-energy-security/111648384?action=profile_completion&utm_source=Mailer&utm_medium=newsletter&utm_campaign=etenergy_news_2024-07-11&dt=2024-07-11&em=c2FuYS5zYXByYTIyMUBnbWFpbC5jb20.

[iii]Shameem Prashantham and Lola Woetzel, “To Create a Greener Future, the West Can’t Ignore China,” Harvard Business Review, April 10, 2024, https://hbr.org/2024/05/to-create-a-greener-future-the-west-cant-ignore-china.

[iv]“Fact Sheet: President Biden Takes Action to Protect American Workers and Businesses from China’s Unfair Trade Practices,” The White House, May 14, 2024, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/05/14/fact-sheet-president-biden-takes-action-to-protect-american-workers-and-businesses-from-chinas-unfair-trade-practices/?utm_source=dailybrief&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=DailyBrief2024May14&utm_term=DailyNewsBrief.

[v]Noah J. Gordon et al., “Why US-China Rivalry Can Actually Help Fight Climate Change,” Internationale Politik Quarterly, March 24, 2023, https://ip-quarterly.com/en/why-us-china-rivalry-can-actually-help-fight-climate-change.

[vi] Simon Evans Hongqiao Liu, “The Carbon Brief Profile: China,” Carbon Brief, November 30, 2023, https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-china/.

[vii]“Climatechange,” United Nations, accessed July 18, 2024, https://www.un.org/en/climatechange#:~:text=The%20world’s%20largest%20standalone%20public,to%20tackle%20the%20climate%20crisis.

[viii]Martin Jacques, “China Will Reach Climate Goal While West Falls Short,” Global Times, accessed July 19, 2024, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202402/1306788.shtml#:~:text=There%20has%20been%20constant%20low,than%202050%20for%20carbon%20zero.

[ix] Steven Lee Myers, “China’s Pledge to Be Carbon Neutral by 2060: What It Means,” The New York Times, September 23, 2020

[x] Simon Evans, Hongqiao Liu et al, “The Carbon Brief Profile: China,” Carbon Brief, November 30, 2023, https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-china/.

[xi] China | nationally determined contribution (NDC), accessed July 17, 2024, https://www.climatewatchdata.org/ndcs/country/CHN?document=revised_first_ndc.

[xii] Simon Evans, Hongqiao Liu et al, “The Carbon Brief Profile: China,” Carbon Brief, November 30, 2023, https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-china/.

[xiii] Steven Lee Myers, “China’s Pledge to Be Carbon Neutral by 2060: What It Means,” The New York Times, September 23, 2020,https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/23/world/asia/china-climate-change.html.

[xiv] Steven Lee Myers, “China’s Pledge to Be Carbon Neutral by 2060: What It Means,” The New York Times, September 23, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/23/world/asia/china-climate-change.html.

[xv] Simon Evans, Hongqiao Liu et al, “The Carbon Brief Profile: China,” Carbon Brief, November 30, 2023, https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-china/.

[xvi] Matt McGrath, “Climate Change: China Aims for ‘Carbon Neutrality by 2060,’” BBC News, September 22, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-54256826.

[xvii] Simon Evans, Hongqiao Liu et al, “The Carbon Brief Profile: China,” Carbon Brief, November 30, 2023, https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-china/.

[xviii] World Bank Group, “China Country Climate and Development Report,” Open Knowledge Repository, October 2022, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/ef01c04f-4417-51b6-8107-b688061a879e.

[xix] World Bank Group, “China Country Climate and Development Report,” Open Knowledge Repository, October 2022, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/ef01c04f-4417-51b6-8107-b688061a879e.

[xx] World Bank Group, “China Country Climate and Development Report,” Open Knowledge Repository, October 2022, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/ef01c04f-4417-51b6-8107-b688061a879e.

[xxi] Steven Lee Myers, “China’s Pledge to Be Carbon Neutral by 2060: What It Means,” The New York Times, September 23, 2020.

[xxii] Steven Lee Myers, “China’s Pledge to Be Carbon Neutral by 2060: What It Means,” The New York Times, September 23, 2020.

[xxiii] Simon Evans, Hongqiao Liu et al, “The Carbon Brief Profile: China,” Carbon Brief, November 30, 2023, https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-china/.

Feature Image: wionews.com China leads the charge: Beijing develops two-thirds of global wind and solar projects.