Key Points

- IT hardware and Semiconductor manufacturing has become strategically important and critical geopolitical tools of dominant powers. Ukraine war related sanctions and Wassenaar Arrangement regulations invoked to ban Russia from importing or acquiring electronic components over 25 Mhz.

- Semi conductors present a key choke point to constrain or catalyse the development of AI-specific computing machinery.

- Taiwan, USA, South Korea, and Netherlands dominate the global semiconductor manufacturing and supply chain. Taiwan dominates the global market and had 60% of the global share in 2021. Taiwan’s one single company – TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co), the world’s largest foundry, alone accounted for 54% of total global revenue.

- China controls two-thirds of all silicon production in the world.

- Monopolisation of semiconductor supply by a singular geopolitical bloc poses critical challenges for the future of Artificial Intelligence (AI), exacerbating the strategic and innovation bottlenecks for developing countries like India.

- Developing a competitive advantage over existing leaders would require not just technical breakthroughs but also some radical policy choices and long-term persistence.

- India should double down over research programs on non-silicon based computing with a national urgency instead of pursuing a catch-up strategy.

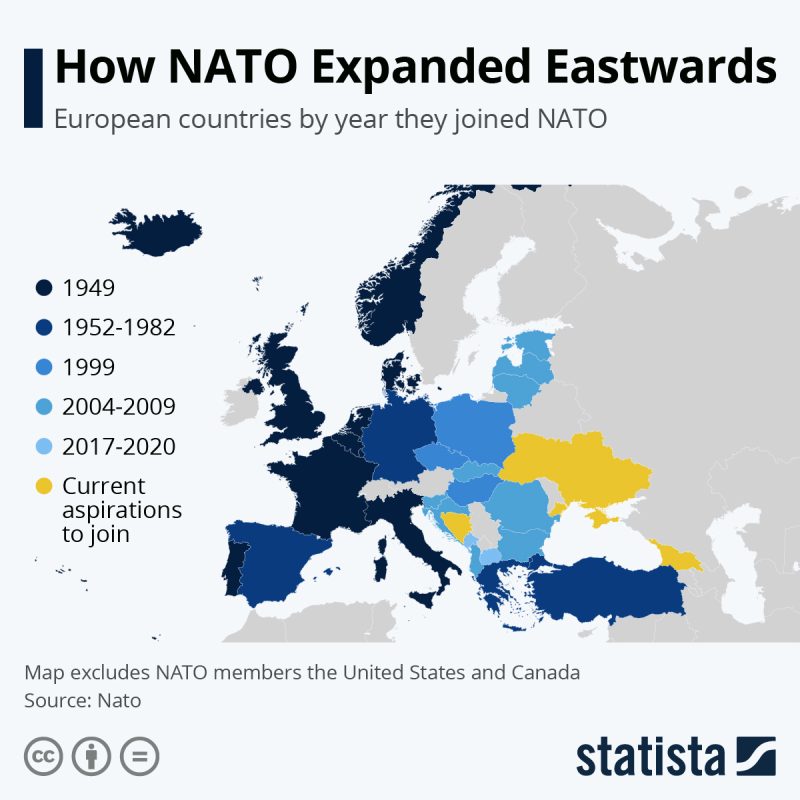

Russia was recently restricted, under category 3 to category 9 of the Wassenaar Arrangement, from purchasing any electronic components over 25MHz from Taiwanese companies. That covers pretty much all modern electronics. Yet, the tangibles of these sanctions must not deceive us into overlooking the wider impact that hardware access and its control have on AI policies and software-based workflows the world over. As Artificial Intelligence technologies reach a more advanced stage, the capacity to fabricate high-performance computing resources i.e. semiconductor production becomes key strategic leverage in international affairs.

Semiconductors present a key chokepoint to constrain or catalyse the development of AI-specific computing machinery. In fact, most of the supply of semiconductors relies on a single country – Taiwan. The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC) manufactures Google’s Tensor Processing Unit (TPU), Cerebras’s Wafer Scale Engine (WSE), as well as Nvidia’s A100 processor. The following table provides a more detailed1 assessment:

|

Hardware Type |

AI Accelerator/Product Name |

Manufacturing Country |

|

Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) |

Huawei Ascend 910 |

Taiwan |

|

Cerebras WSE |

Taiwan |

|

|

Google TPUs |

Taiwan |

|

|

Intel Habana |

Taiwan |

|

|

Tesla FSD |

USA |

|

|

Qualcomm Cloud AI 100 |

Taiwan |

|

|

IBM TrueNorth |

South Korea |

|

|

AWS Inferentia |

Taiwan |

|

|

AWS Trainium |

Taiwan |

|

|

Apple A14 Bionic |

Taiwan |

|

|

Graphic Processing Units (GPUs) |

AMD Radeon |

Taiwan |

|

Nvidia A100 |

Taiwan |

|

|

Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) |

Intel Agilex |

USA |

|

Xilinx Virtex |

Taiwan |

|

|

Xilinx Alveo |

Taiwan |

|

|

AWS EC2 FI |

Taiwan |

As can be seen above, the cake of computing hardware is largely divided in such a way that the largest pie holders also happen to form a singular geopolitical bloc vis-a-vis China. This further shapes the evolution of territorial contests in the South China Sea. This monopolisation of semiconductor supply by a singular geopolitical bloc poses critical challenges for the future of Artificial Intelligence, especially exacerbating the strategic and innovation bottlenecks for developing countries like India. Since the invention of the transistor in 1947, and her independence, India has found herself in an unenviable position where there stands zero commercial semiconductor manufacturing capacity after all these years while her office-bearers continually promise of leading in the fourth industrial revolution.

Bottlenecking Global AI Research

There are two aspects of developing these AI accelerators – designing the specifications and their fabrication. AI research firms first design chips which optimise hardware performance to execute specific machine learning calculations. Then, semiconductor firms, operating in a range of specialities and specific aspects of fabrication, make those chips and increase the performance of computing hardware by adding more and more transistors to pieces of silicon. This combination of specific design choices and advanced hardware fabrication capability forms the bedrock that will decide the future of AI, not the amount of data a population is generating and localising.

However, owing to the very high fixed costs of semiconductor manufacturing, AI research has to be focused on data and algorithms. Therefore, innovations in AI’s algorithmic efficiency and model scaling have to compensate for a lack of equivalent situations in the AI’s hardware. The aggressive consolidation and costs of hardware fabrication mean that firms in AI research are forced to outsource their hardware fabrication requirements. In fact, as per DARPA2, because of the high costs of getting their designs fabricated, AI hardware startups do not even receive much private capital and merely 3% of all venture funding between 2017-21 in AI/ML has gone to startups working on AI hardware.

But TSMC’s resources are limited and not everyone can afford them. To get TSMC’s services, companies globally have to compete with the likes of Google and Nvidia, therefore prices go further high because of the demand side competition. Consequently, only the best and the biggest work with TSMC, and the rest have to settle for its competitors. This has allowed this single company to turn into a gatekeeper in AI hardware R&D. And as the recent sanctions over Russia demonstrate, it is now effectively playing the pawn which has turned the wazir in a tense geopolitical endgame.

Taiwan’s AI policy also reflects this dominance in ICT and semiconductors – aiming to develop “world-leading AI-on-Device solutions that create a niche market and… (make Taiwan) an important partner in the value chain of global intelligent systems”.3 The foundation of strong control over the supply of AI hardware and also being #1 in the Global Open Data Index, not just gives Taiwan negotiating leverage in geopolitical competition, but also allows it to focus on hardware and software collaboration based on seminal AI policy unlike most countries where the AI policy and discourse revolve around managing the adoption and effects of AI, and not around shaping the trajectory of its engineering and conceptual development like the countries with hardware advantage.

Now to be fair, R&D is a time-consuming, long-term activity which has a high chance of failure. Thus, research focus naturally shifts towards low-hanging fruits, projects that can be achieved in the short-term before the commissioning bureaucrats are rotated. That’s why we cannot have a nationalised AGI research group, as nobody will be interested in a 15-20 year-long enterprise when you have promotions and election cycles to worry about. This applies to all high-end bleeding-edge technology research funding everywhere – so, quantum communications will be prioritised over quantum computing, building larger and larger datasets over more intelligent algorithms, and silicon-based electronics over researching newer computing substrates and storage – because those things are more friendly to short-term outcome pressures and bureaucracies aren’t exactly known to be a risk-taking institution.

Options for India

While China controls 2/3 of all the silicon production in the world and wants to control the whole of Taiwan too (and TSMC along with its 54% share in logic foundries), the wider semiconductor supply chain is a little spreadout too for any one actor’s comfort. The leaders mostly control a specialised niche of the supply chain, for example, the US maintains a total monopoly on Electronic Design Automation (EDA) software solutions, the Netherlands has monopolised Extreme UltraViolet and Argon Flouride scanners, and Japan has been dishing out 300 mm wafers used to manufacture more than 99 percent of the chips today.4 The end-to-end delivery of one chip could have it crossing international borders over 70 times.5 Since this is a matured ecosystem, developing a competitive advantage over existing leaders would require not just proprietary technical breakthroughs but also some radical policy choices and long term persistence.

It is also needless to say that the leaders are also able to attract and retain the highest quality talent from across the world. On the other hand, we have a situation where regional politicians continue cribbing about incoming talent even from other Indian states. This is therefore the first task for India, to become a technology powerhouse, she has to, at a bare minimum, be able to retain all her top talent and attract more. Perhaps, for companies in certain sectors or of certain size, India must make it mandatory to spend at least X per cent of revenue on R&D and offer incentives to increase this share – it’ll revamp things from recruitment and retention to business processes and industry-academia collaboration – and in the long-run prove to be a lot more socioeconomically useful instrument than the CSR regulation.

It should also not escape anyone that the human civilisation, with all its genius and promises of man-machine symbiosis, has managed to put all its eggs in a single basket that is also under the constant threat of Chinese invasion. It is thus in the interest of the entire computing industry to build geographical resiliency, diversity and redundancy in the present-day semiconductor manufacturing capacity. We don’t yet have the navy we need, but perhaps in a diplomatic-naval recognition of Taiwan’s independence from China, the Quad could manage to persuade arrangements for an uninterrupted semiconductor supply in case of an invasion.

Since R&D in AI hardware is essential for future breakthroughs in machine intelligence – but its production happens to be extremely concentrated, mostly by just one small island country, it behoves countries like India to look for ways to undercut the existing paradigm of developing computing hardware (i.e. pivot R&D towards DNA Computing etc) instead of only trying to pursue a catch-up strategy. The current developments are unlikely to solve India’s blues in integrated circuits anytime soon. India could parallelly, and I’d emphatically recommend that she should, take a step back from all the madness and double down on research programs on non-silicon-based computing with a national urgency. A hybrid approach toward computing machinery could also resolve some of the bottlenecks that AI research is facing due to dependencies and limitations of present-day hardware.

As our neighbouring adversary Mr Xi says, core technologies cannot be acquired by asking, buying, or begging. In the same spirit, even if it might ruffle some feathers, a very discerning reexamination of the present intellectual property regime could also be very useful for the development of such foundational technologies and related infrastructure in India as well as for carving out an Indian niche for future technology leadership.

References:

1. The Other AI Hardware Problem: What TSMC means for AI Compute. Available at https://semiliterate.substack.com/p/the-other-ai-hardware-problem

2. Leef, S. (2019). Automatic Implementation of Secure Silicon. In ACM Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI (Vol. 3)

3. AI Taiwan. Available at https://ai.taiwan.gov.tw/

4. Khan et al. (2021). The Semiconductor Supply Chain: Assessing National Competitiveness. Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

5. Alam et al. (2020). Globality and Complexity of the Semiconductor Ecosystem. Accenture.