[powerkit_button size=”lg” style=”info” block=”true” url=”https://admin.thepeninsula.org.in/2022/03/29/tpf-analysis-series-on-russia-ukraine-conflict/” target=”_blank” nofollow=”false”]

The First Paper of the Series – TPF Analysis Series on Russia – Ukraine Conflict #1

[/powerkit_button]

What’s in Ukraine for Russia?

In a press conference marking his first year in office, President Biden, on the question of Russia invading Ukraine, remarked that such an event would, “be the most consequential thing that’s happened in the world, in terms of war and peace, since World War Two”. [1] It has now been two months since Russia officially launched its “special military operation” in Ukraine, which the US and its allies consider an unjustified invasion of a sovereign state. The conflict in the Eurasian continent has drawn global attention to Europe and US-Russia tensions have ratcheted to levels that were prevalent during the Cold War. The conflict has also raised pertinent questions on understanding what exactly are Russian stakes in Ukraine and the latter’s role in the evolving security architecture of Europe. The second paper in this series will delve into these questions.

The current Russian position stems from the experience that Russia, and Putin, gained while dealing with the West on a host of issues, not least of which was NATO expansion.

The Ties that Bind

An examination of post-Soviet history reveals that Russian preoccupation with security threats from NATO is not embedded in Russian geopolitics; instead, it has been reported that, early on, Russia was even agreeable to joining the military alliance. The current Russian position stems from the experience that Russia, and Putin, gained while dealing with the West on a host of issues, not least of which was NATO expansion. A line of argument sympathetic to Russia is President Putin’s contention that terms dictated to Russia during the post-Cold War settlements were unfair. The claim is a reference to Secretary of State James Baker’s statement on the expansion of NATO, “not an inch of NATO’s present military jurisdiction will spread in an eastern direction”, in 1990 in a candid conversation with Mikhael Gorbachev on the matter of reunification of Germany. [2] It could be argued that it is this commitment and subsequent violation through expansions of NATO is one of the main causes of the current conflict.

At the root of the problem was Russia’s security concerns – regarding both traditional and hybrid security – that ultimately led to the centralisation of power after a democratic stint under Yeltsin. Accordingly, Putin had put it in late 1999, “A strong state for Russia is not an anomaly, or something that should be combated, but, on the contrary, the source and guarantor of order, the initiator and the main driving force of any changes”. [3]

Historically being a land power, Russia has viewed Ukraine as a strategically critical region in its security matrix. However, as the central control of Moscow weakened in the former USSR, the nationalist aspirations of the Ukrainian people began to materialise and Ukraine played a crucial role, along with the Russian Federation and Belarus, in dissolving the former Soviet Union. The two countries found themselves on opposite sides on extremely fundamental issues, such as security, economic partnership, post-Soviet order, and, not least, sovereignty. In Belovezh, in early December of 1991, when Russian President Boris Yeltsin, Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk and Belarusian leader Stanislav Shushkevich met to dissolve the USSR, major disagreements regarding the transitional phase and future of the republics erupted. Yeltsin expressed his desire for some sort of central control of the republics, whereas Kravchuk was vehemently opposed to any arrangement that might compromise his country’s sovereignty. Later, at the foundational ceremony of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), he stressed a common military, the most potent rejection of which came from Kravchuk. [4]

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The elephant in the room, however, was the status of Sevastopol, which housed the headquarters of the Black Sea Fleet. Yeltsin was quoted saying that “The Black Sea Fleet was, is and will be Russia’s. No one, not even Kravchuk will take it away from Russia”. [5] Though the issue was soon temporarily resolved –with the two countries dividing the fleet equally amongst themselves, it continued to dominate and sour their relationship. Russia, as the successor state of the USSR, wanted the base and the entire fleet in its navy. Yeltsin even offered gas at concessional rates to Ukraine if it handed over the city and nuclear weapons to Russia. The issue remained unresolved until the 1997 Friendship Treaty under which Ukraine granted Moscow the entire fleet and leased Sevastopol to Russia until 2017 (later extended).

Ukraine, under Kravchuk and, later, Leonid Kuchma, struggled to tread a tightrope between Russia and the European Union. On one hand, it was economically knit with former Soviet Republics, and on the other, it was actively looking to get economic benefits from the EU. However, soon a slide towards the west was conspicuous. In 1994, it preferred a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement with the EU over CIS Customs Union, which was a Russian initiative. Later, in 1996, it declined to join a new group consisting of former Soviet Republics ‘On Deepening Integration’, scuttling the initiative, since its purpose was to bring Ukraine back into the Russian fold. [6] By 1998, the Kuchma government had formulated a ‘Strategy of Integration into the European Union’. [7]

Nuclear weapons were another point of contention between the two. Ukraine was extremely reluctant to give up its arsenal, citing security threats from Russia. Kravchuk received a verbal ‘security guarantee’ from the US which forced Russia to “respect the independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity of each nation” [8] in exchange for surrendering Ukraine’s nuclear weapons.

Notwithstanding the disputes, there was a great deal of cooperation between the two, especially after Kuchma’s re-election in 1999. Kuchma’s hook-up with authoritarianism distanced Kyiv from Brussels and brought it closer to Moscow. Ukraine agreed to join Russian initiatives of the Eurasian Economic Community as an observer and Common Economic Space as a full member. At home as well, his support in the eastern parts of the country, where ethnic Russians dwelled, increased dramatically, as evident in the 2002 Parliamentary Elections. [9] However, the bonhomie was soon disrupted by a single event.

The Orange Revolution was Russia’s 9/11. [10] It dramatically altered Russian thinking on democracy and its ties with the West. It raised the prospect in Russia that Ukraine might be lost completely. It further made them believe the colour revolutions in former Soviet republics were CIA toolkits for regime change. More importantly, it made the Russians apprehensive of a similar revolution within their borders. As a result, the distrust between Russia and the West, and Russia and Ukraine grew considerably. As a nationalist, Victor Yushchenko formulated policies that directly hurt Russian interests. The two countries fought ‘Gas Wars’ in 2006 and 2009, which made both the EU and Russia uncomfortable with Ukraine as a gas transit country. Furthermore, Yushchenko bestowed the title of ‘Hero of Ukraine’ upon Stepan Bandera, a Nazi collaborator and perpetrator of the Holocaust, a decision that surely did not go well with Moscow.

Geoeconomics: Ukraine as a Gas Transit Country

The current war is the worst in Europe since the Second World War. Still, Ukraine continues to transit Russian gas through its land, Russia continues to pay for it, and Western Europe continues to receive the crucial resource. The war has shattered all the big bets on Russian dependence on Ukraine for delivering gas to Western Europe and has renewed the discourse on reducing European energy dependence on Russia. Since the EU imports 40% of its gas from Russia, almost a quarter of which flows through Ukraine, Kyiv has had leverage in dealing with Russians in the past. It has been able to extract favourable terms by either stopping or diverting gas for its own domestic use at a time of heightened tensions between Ukraine and Russia. As a result, the EU was directly drawn into the conflict between them, infructuating Moscow’s pressure tactics for a long.

Moscow has made numerous attempts in the past to bypass Ukraine by constructing alternate pipelines. Nord Stream, the most popular of them, was conceived in 1997, as an attempt to decrease the leverage of the transit states. The pipeline was described as the “Molotov-Ribbentrop Pipeline” by Polish Defence Minister Radoslaw Sirkosi for the geoeconomic influence it gave to Russia. [11] Another project – the South Stream – was aimed at providing gas to the Balkans, and through it to Austria and Italy. The pipeline was conceived in the aftermath of the Orange Revolution and its construction was motivated by geoeconomics, rather than economic viability. It would have led to Russia bypassing Ukraine in delivering gas to the Balkans and Central Europe, thus seizing its significant leverage, and relegating it to vulnerable positions in which Moscow could have eliminated the gas subsidies Ukraine was being provided. [12]As a result of economic unviability, the project was abandoned in 2014.

To a certain extent, the European Union has been complicit in making matters worse for Russia. For instance, during the 2009 ‘Gas War’ – that began due to Ukraine’s non-payment of gas debt to Russia – instead of holding Ukraine accountable, the EU countries blamed Russia for the gas crisis in Europe and asked Russia to resume gas supply to Ukraine. Later, realising the importance of Ukraine as a transit country, it reached an agreement with Kyiv that “recognized the importance of the further expansion and modernization of Ukraine’s gas transit system as an indispensable pillar of the common European energy infrastructure, and the fact that Ukraine is a strategic partner for the EU gas sector”. The agreement excluded Russia as a party, which saw it as undermining the collaboration between itself and Ukraine, and injuring its influence on the country. [13] The Russian grievance becomes even more palpable when we view the significant gas subsidies it has provided to Ukraine for more than two decades.

Similarly, the EU countries viewed Nord Stream 2 from a geostrategic and geo-economic perspective. In December last year, German Economic Affairs Minister Robert Habeck warned Russia of halting Nord Stream 2 if it attacks Ukraine. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was quoted saying that he would do ‘anything’ to ensure that Ukraine remains a transit country for Russian gas. [14] In fact, the pipeline – that is set to double the capacity of gas delivered to the EU – has faced opposition from almost all Western European countries, the US, the EU as well as Ukraine, which has described it as ‘A dangerous Geopolitical Weapon’. [15] The pipeline had raised concerns amongst Ukrainians of losing a restraining factor on Moscow’s behaviour. [16] However, with the pipeline still inoperable, the Kremlin has already made the restraining factor ineffective.

The Security Objective

The Russian Federation is a country which spreads from the European Continent to Asia. In this giant nation, the hospitable region where people live is mainly on the European side, which also comprises main cities like St. Petersburg, Volgograd and the Capital City Moscow. Throughout history, Russia has seen invasions by Napoleon as well as Hitler, and the main area through which these invasions and wars happened was through Ukrainian land which gave them direct access to Russia – due to the lack of any geographical barriers. It was certainly a contributing factor towards the initial success of these invasions. Today, we might understand these events as Russia’s sense of vulnerability and insecurity if history is any indicator.

The Russian Federation also follows a similar approach to ensuring its security, survival and territorial integrity. Russia’s interest in Ukraine is as much geopolitical as cultural. Since Russians and Ukrainians were intrinsically linked through their culture and language, Ukraine quickly came to be seen as Russian land, with Ukrainians being recognized as ‘Little Russians’ (Kubicek, 2008), as compared to the “Great Russians”. They were consequently denied the formation of a distinct Ukrainian identity. Putin gave substance to this sentiment as, according to a US diplomatic cable leak, he had “implicitly challenged the territorial integrity of Ukraine, suggesting that Ukraine was an artificial creation sewn together from the territory of Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania, and especially Russia in the aftermath of the Second World War” during a Russia-NATO Council meeting. [17]

Crimea and much of eastern Ukraine are ethnically Russian and desire closer ties with Russia. But moving further west, the people become increasingly cosmopolitan and it is mostly this population that seeks greater linkage with the Western European countries and membership into the EU and NATO. This in addition to the Euro Maidan protests is what Putin has used to justify the annexation of Crimea in 2014. The other security consideration was the threat it faced from the likelihood of NATO establishing a base in Crimea given its own presence in Sevastopol in the Black Sea.

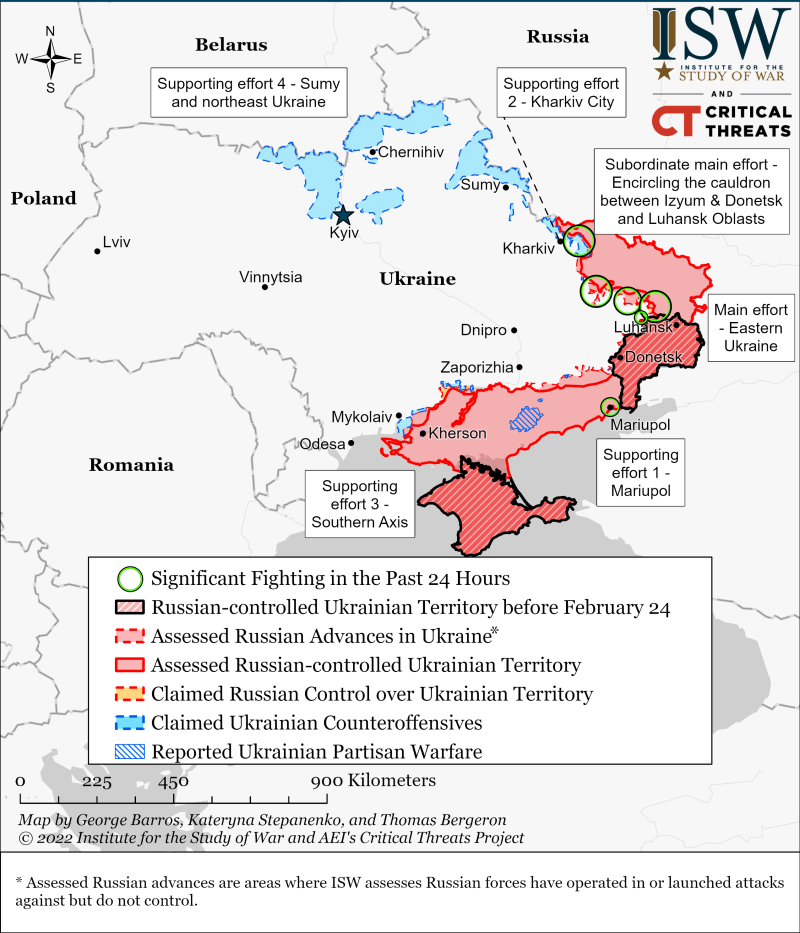

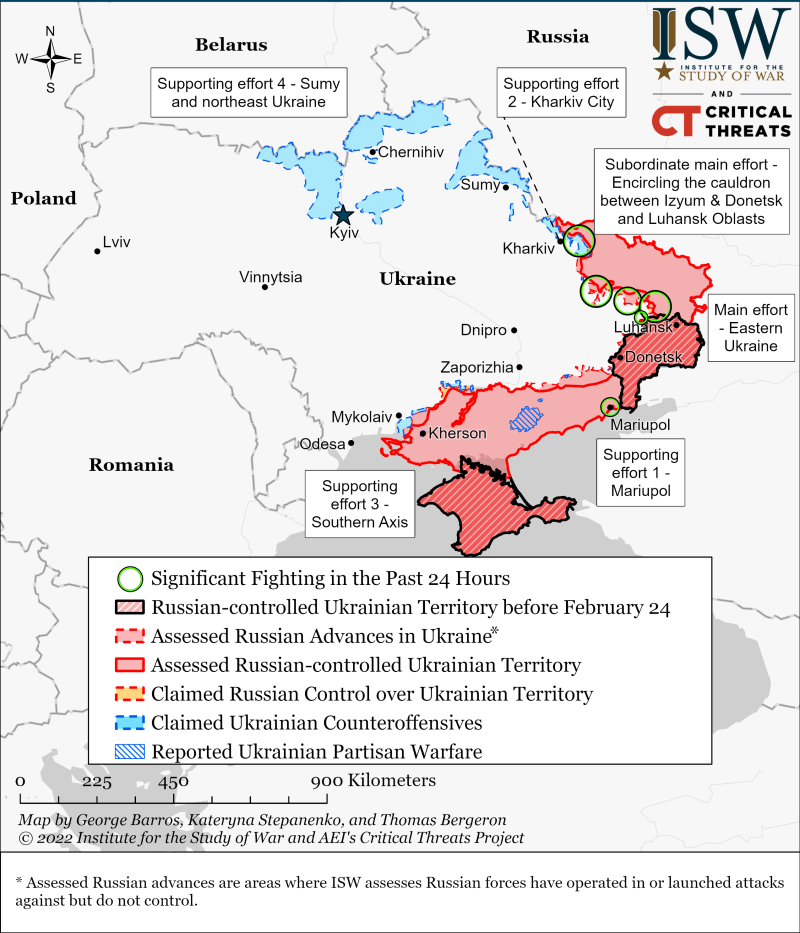

In the current scenario, the second phase of Russian Military operation in the East and South has shown us the larger vulnerabilities Moscow has which are being countered through control of certain points in the region. By liberating the Donbass region in the east, Russia plans to create a buffer zone between itself and the west to stop future aggression and keep enemies at bay. But the extension of this buffer zone all the way to Odessa is indicative of other strategic considerations. Mariupol in the south of Ukraine is one of the many extended strategic points Russia now controls leading us to ask just why Mariupol is a game-changer in this conflict?

The port city of Mariupol is a small area geographically, but it provides the land bridge for the Russian forces in the Crimean Peninsula to join the Military operation in the Donbas region. Moreover, it gives Russia a land bridge to Crimea from the Russian Mainland. According to General Sir Richard Barrons, former Commander of UK Joint Forces Command, Mariupol is crucial to Russia’s offensive movement, – “When the Russians feel they have successfully concluded that battle, they will have completed a land bridge from Russia to Crimea and they will see this a major strategic success.” [18]

Source: ISW (Assessment on 09 May, 2022)

If the port city of Mariupol is important for the creation of a land corridor, then the Sea of Azov which is adjacent to it is even more important due to its strategic position. [19] The three geopolitical reasons why this sea is important are as follows:

- The Sea of Azov is a major point for the economic and military well-being of Ukraine. Proximity to the frontlines of the Donbass region where the fighting between Ukrainian forces and Pro-Russian separatists is taking place makes the control of this sea vital to the Russian military as it helps weaken Ukrainian defence in the region via control of the Kerch Strait.

- Controlling the Sea of Azov is strategically important for Russia, to maintain its control in the Crimean Peninsula, which allows Moscow to resupply its forces through the Strait of Kerch.

- Finally, it also involves Eurasian politics into why Russia needs to control this region and here the discussion of the Volga-Don canal which links the Caspian Sea with the Sea of Azov comes to the fore. Russia has always used this canal to move warships between the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea and project its power in both regions. Moreover, Russia sees this connection as a significant strategic advantage in any future crisis.

If Mariupol and the Sea of Azov are considered the most important strategically valuable features by Russia, there also exists the crucial points of Kherson and Odessa which will give Russia complete dominance of the Ukrainian coast line, thus giving larger access and control in the Black Sea region that has the potential to be militarised in the future in conflicts with the West. Moreover, it gives Russia a land corridor to Transnistria which is a Pro-Russian separatist area in Moldova and an opening into the Romanian border through Odessa, thus balancing the build-up of NATO forces in the region.

Conclusion

The Ukrainian crisis is as much the West’s doing as Russia’s and an ear sympathetic to the Russian narrative might even say that the West took advantage of Russia when it was vulnerable immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union in negotiations regarding the German state reunification and NATO enlargement.

The bottom line is that, presently, Putin views NATO as an existential security threat to the Russian state and sees the US and its allies’ support of Ukraine as a challenge. Ukraine’s membership in the EU and NATO is a non-starter for Russia and pitting a Ukraine, that has a symbiotic relationship with Russia at all levels, against a slightly diminished but still formidable great power will have consequences for the security architecture and geopolitics of the region. The Ukrainian crisis is as much the West’s doing as Russia’s and an ear sympathetic to the Russian narrative might even say that the West took advantage of Russia when it was vulnerable immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union in negotiations regarding the German state reunification and NATO enlargement. On some level, NATO countries recognize the fact that Ukraine and Georgia can never be allowed membership into the North Atlantic alliance because the alternative of wilfully ignoring Russia’s security and national interests is just a recipe for disaster and might just launch the region into the single biggest armed conflict since World War 2.

References:

[1] The White House. (2022, January 20). Remarks by president Biden in the press conference. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/01/19/remarks-by-president-biden-in-press-conference-6/

[2] Savranskaya, S., Blanton, T. S., & Zubok, V. (2010). Masterpieces of history: The peaceful end of the Cold War in Europe, 1989. Central European University Press.

[3] Putin, Vladimir. “Rossiya na Rubezhe Tysyacheletii,” Nesavisimaya Gazeta, December 30, 1999, quoted in D’Anieri, Paul (2019). Ukraine and Russia: From Civilized Divorce to Uncivil War. Cambridge University Press.

[4] Ibid

[5] Rettie, J. and James Meek, “Battle for Soviet Navy,” The Guardian, January 10, 1992

[6] Ibid, no. iii

[7] Solchanyk, R., Ukraine and Russia: The Post-Soviet Transition. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. 2000.

[8] Goldgeier, J. and Michael McFaul. “Power and Purpose: U.S. Policy Toward Russia after the Cold War”, Brookings Institution Press, 2003

[9] Ibid, no. iii

[10] The comment was made by Gleb Pavlovskii, a Russian Political Scientist. quoted in Ben Judah (2013), Fragile Empire: How Russia Fell In and Out of Love with Vladimir Putin. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p. 85.

[11] Ibid, no. iii

[12] Wigell, M. and A. Vihma, Geopolitics versus geoeconomics: the case of Russia’s geostrategy and its effects on the EU. International Affairs, 92: 605-627. May 6, 2016

[13] Ibid, no. iii

[14] Harper, J. (2021, December 23). Nord stream 2: Who wins, who loses? Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/nord-stream-2-who-wins-who-loses/a-60223801

[15] Ukraine: Nord stream 2 a ‘dangerous geopolitical weapon’. (2021, August 22). DW.COM. https://www.dw.com/en/ukraine-nord-stream-2-a-dangerous-geopolitical-weapon/a-58950076

[16] Pifer, S. “Nord Stream 2: Background, Objectives and Possible Outcomes”, Brookings, April 2021 https://www.brookings.edu/research/nord-stream-2-background-objections-and-possible-outcomes/

[17] WikiLeaks. (2008, August 14). UKRAINE, MAP, AND THE GEORGIA-RUSSIA CONFLICT, Canonical ID:08USNATO290_a. https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08USNATO290_a.html

[18] Gardner, F. (2022, March 21). Mariupol: Why Mariupol is so important to Russia’s plan. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-60825226

[19] Blank, S. (2018, November 6). Why is the Sea of Azov so important? Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/why-is-the-sea-of-azov-so-important/

Featured Image Credits: Financial Times

[powerkit_button size=”lg” style=”info” block=”true” url=”https://admin.thepeninsula.org.in/2022/03/29/tpf-analysis-series-on-russia-ukraine-conflict/” target=”_blank” nofollow=”false”]

TPF Analysis Series on Russia – Ukraine Conflict #1

[/powerkit_button]

ALFREDO TORO HARDY is a Venezuelan retired diplomat, scholar and author. He has a PhD in International Relations from the Geneva School of Diplomacy and International Affairs, two master’s degrees in international law and international economics from the University of Pennsylvania and the Central University of Venezuela, a post-graduate diploma in diplomatic studies by the Ecole Nationale D’Administration (ENA) and a Bachelor of Law degree by the Central University of Venezuela. Before resigning from the Venezuelan Foreign Service in protest of events taking place in his country, he was one of its most senior career diplomats. As such, he served as Ambassador to the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil, Singapore, Chile and Ireland.

ALFREDO TORO HARDY is a Venezuelan retired diplomat, scholar and author. He has a PhD in International Relations from the Geneva School of Diplomacy and International Affairs, two master’s degrees in international law and international economics from the University of Pennsylvania and the Central University of Venezuela, a post-graduate diploma in diplomatic studies by the Ecole Nationale D’Administration (ENA) and a Bachelor of Law degree by the Central University of Venezuela. Before resigning from the Venezuelan Foreign Service in protest of events taking place in his country, he was one of its most senior career diplomats. As such, he served as Ambassador to the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil, Singapore, Chile and Ireland.