Introduction

Over the last few decades, migration has become a global norm. Although a substantial part of the global population migrates for economic and personal reasons, it is undeniable that migration as a phenomenon is exacerbated by factors such as armed conflicts, ethnic or politico-social tensions, climate change and others. The effect that migration has on global economic, social and political transformations is widely recognized.[1] Naturally, in contrast to migration policies, all States have specific laws to regulate the acquisition of nationality by birth, descent and/or naturalization. While most of us realise the significance of the concept of nationality, we tend to overlook the fact that inclusion by nationality often brings the phenomenon of statelessness with it. In this context, the latest developments in the Indian laws regulating nationality raise several social and legal conundrums. However, the lack of any legal framework on statelessness or India’s abstinence from signing the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons or the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness is a clear indication of India’s unpreparedness to deal with the potential long-term consequences of its new laws.

Deprivation of Citizenship and Statelessness in the Contemporary Era

The concepts of nationality and citizenship have attracted great attention for raising several contemporary politico-legal and social issues. Citizenship confers an identity on an individual within a particular state. Consequently, a citizen is able to derive rights and is assigned obligations by virtue of this identity.[2] Political Philosopher, Hannah Arendt, terms this as “the right to have rights”.[3] Citizenship is what entitles a citizen to the full membership of rights, a democratic voice and territorial residence. While we understand the significance of being a citizen of a country, we often fail to ponder upon the consequences of losing it. Immanuel Kant argues that citizenship by naturalisation is a sovereign privilege and the obverse side of such privilege is the loss of citizenship or “denationalisation”.[4] Arendt has also identified the twin phenomena of “political evil” and “statelessness”.[5]

This condition of statelessness is not only a harmful condition which makes the person vulnerable to violation of human rights, but it also works in delegitimising a person in the socio-legal order of a State.

An introspect into the right to have the right to a nationality goes on to throw light on the issue of statelessness. Although history has proven the existence of both de facto and de jure statelessness, this chapter is only concerned with de jure statelessness, specifically within the Indian context. The Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons defines a “stateless person” as ‘a person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law’.[6] This condition of statelessness is not only a harmful condition which makes the person vulnerable to violation of human rights, but it also works in delegitimising a person in the socio-legal order of a State.[7] The number of stateless persons globally in the year 2018 was 3.9 million.[8] This number is still regarded as a conservative under-estimation owing to the fact that most of the affected population reside precariously within the society and most countries do not calculate comprehensive statistics of stateless persons within their territory. UNHCR estimates at least a global figure of 10 million stateless persons globally.[9]

Statelessness hinders the day-to-day life of a person by depriving them of access to the most rudimentary rights like education, employment or health care to name a few. It may be attributed to multiple causes inter-alia discrimination, denationalization, lack of documentation, climate change, forced migration, conflict of laws, boundary disputes, state succession and administrative practices.[10] Discrimination based on ethnicity, race, religion or language has been a constant cause of statelessness globally. Currently, at least 20 countries uphold laws which can deny or deprive a person of their nationality in a discriminatory manner.[11] Statelessness tends to exaggerate impact of discrimination and exclusion that minority groups might already be facing. It widens the gap between communities thus deepening their exclusion.[12] The phenomenon of statelessness has been the more prominent in South and South East Asian countries. The Hill Tamil repatriates in India from Sri Lanka and the Burmese refugees in Cambodia are examples of Asian Stateless populations who are vulnerable to human rights abuses. The 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness are the two most important conventions addressing this issue. The former has 94 parties and 23 signatories, and the latter has 75 parties and only 5 signatories. Albeit international legal norms on the issue of statelessness have restrained the States’ denationalisation power, it has however not erased the use of discrimination as a tool for denationalization.[13] This has been particularly relevant in the case of naturalization of nationals from Muslim-majority countries.[14] It can be argued that India’s Citizenship Amendment Act has also joined this bandwagon.

Interplay of the NRC and Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019

The Citizenship Amendment Act which was passed by the Indian Parliament on 11th December 2019 has caused a lot of uproar and outbreak of protests all over the country. This Act has attracted wide international condemnation[15] for being discriminatory[16], arbitrary and unconstitutional.[17] Before we go on to scrutinise the role of Citizenship Amendment Act in statelessness creation, an analysis of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) is warranted. The NRC process has been the source of several issues regarding migration, citizenship and polarisation of political support in the state of Assam. It has culled out a distinct space in mobilising the political discourse in Assam specifically during the 2014 and 2019 parliamentary elections.[18]

The NRC is a register containing names of Indian Citizens. This register was prepared for the very first time in the year 1951 based on the data collected during census. This process was done subsequent to various groups[19] causing agitation in Assam over the non-regulation of immigrant inflow into the region. This resulted in resorting to laws like the Foreigners Act, 1946 and Foreigners (Tribunal) Order, 1939. The contrast in India’s approach to disregard the aforementioned laws to accommodate people escaping violence in West Pakistan[20] is to be noted here. The NRC process in Assam determines illegal migrants based on their inability to prove the nexus between their documented ancestral legacy to the Indian State. The NRC process defined such illegal immigrants irrespective of their religious affinity. The cut-off date used to determine a person’s ability to prove ancestral legacy was set to March 24, 1971 which is in line with Bangladesh’s war of liberation.

Despite the criticisms and drawbacks, the NRC process is in fact a much needed exercise in the State of Assam. Owing to its shared border with Bangladesh, Assam has been the gateway for refugees, economic and illegal migrants who come to India.

As Assam has been a hub for labour migration right from the colonial era, the ethnic Assamese have been insecure about the potential demographic shifts in favour of the ethnic Bengali migrants, for a long time.[21] This concern was exacerbated by the mass influx of Bengali migrants after the birth of Bangladesh. This mass migration which aggravated the already anti-immigrant sentiment culminated in a student-led movement in the 1970s and 1980s.[22] A series of protests broke out in the Assam to pressure the government to identify and expel illegal immigrants. In the year 1985, the Union government and the AASU signed the Assam Accord by which the government assured the establishment of a mechanism to identify “foreigners who came to Assam on or after March 25, 1971” and subsequently take practical steps to expel them.[23] Consequent to a Public Interest Litigation[24] filed in 2009. In the year 2014, the Supreme Court assumed the role of monitoring the process of updating the NRC to identify Indian citizens residing in Assam in accordance with the Citizenship Act of 1955. The very first draft of the process was published in December 2017 and 1.9 million people were left out of the register from a population of 3.29 million people in Assam.[25] In August 31, 2019, the final list was published which left out 4 million residents from the NRC.[26] Neither drafts of the NRC specifically mention the religion or community of the non-included applicants, although certain commentators[27] and media outlets[28] have alleged that five out of nine Muslim-majority districts of Assam had the maximum number of rejections of applicants.[29] Out of the 4 million applications which were excluded from the final list, 0.24 applicants have been put on ‘hold’. These people belong to categories: D (doubtful) voters, descendants of D-voters, people whose cases are pending at Foreigners Tribunals and descendants of these persons.[30] The NRC process has for long attracted mixed reviews. Scholars have suggested that the process has been an arbitrary one that is aimed more at exclusion[31] than inclusion.[32] It has also been regarded as an expensive process, the brunt of which is borne substantially by the people of India.[33] Despite the criticisms and drawbacks, the NRC process is in fact a much needed exercise in the State of Assam. Owing to its shared border with Bangladesh, Assam has been the gateway for refugees, economic and illegal migrants who come to India. This not only led to the cultural identity crises of Assamese people but it also significantly influenced the political operations in the State.[34] It is also important to note that, owing to the absence of a concrete refugee law in place and due to the general population’s lack of awareness about refugees in India, the distinction between refugees, illegal migrants and economic migrants often get muddled. This is reflected in the anti-migration narrative that brews in the State. Although we maintain that the NRC process is not necessarily a communal exercise, it does have seem to have such repercussions when read together with the Citizenship Amendment Act which was passed by the Indian Parliament last year.

The Preamble of the Indian Constitution recognises the India as a secular state. This has also been reiterated in landmark Supreme Court decisions, whereby the principle of secularism has been recognised as one of the basic structures of the Constitution.Therefore, the fact that the Citizenship Amendment Act discriminates migrants based on their religion, makes is fundamentally unconstitutional.

According to the Indian citizenship Act of 1955, an “illegal migrant” is a foreigner who enters India without a valid passport or such other prescribed travel documentation.[35] The Citizenship Amendment Act, amends this definition. The Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 is not just discriminatory, but it also goes against the basic principles of the Constitution of India. This Act provides that ‘any person belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian community for Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan’, who entered into India on or before December 31, 2014 who have been exempted by the central government by the Passport Act, 1920 or the Foreigners Act 1946, shall not be treated as an illegal migrant.[36] Further, the Act has reduced the aggregate period of residence to qualify for naturalization from 11 years to 5 years for the aforementioned communities.[37] This Act has attracted worldwide criticism from various human rights groups and international organizations. The alleged raison d’etre for the Act is two fold – the alleged religious persecution of minorities in the three Muslim-majority countries mentioned before and rectifying the misdeeds of partition.[38] However, on a careful scrutiny, both these reasons fail to stand the test of rationale and reasonableness. Firstly, it has to be noted that prima facie the Act violates Art.14 of the Indian Constitution by specifically enacting a law that discriminates based on a person’s religion. Documented evidence of persecution of the Islamic minority sects such as the Shias[39] [40], Baloch[41] and Ahmadis[42] [43] in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan is existent. Therefore, the contention that people belonging to Islamic sects would not have faced persecution in Muslim-majority countries is misconceived and simply wrong. Unlike Israel[44], India does not have a ‘Law of Return’. The Preamble of the Indian Constitution recognises the India as a secular state. This has also been reiterated in landmark Supreme Court decisions, whereby the principle of secularism has been recognised as one of the basic structures of the Constitution.[45] Therefore, the fact that the Citizenship Amendment Act discriminates migrants based on their religion, makes is fundamentally unconstitutional.

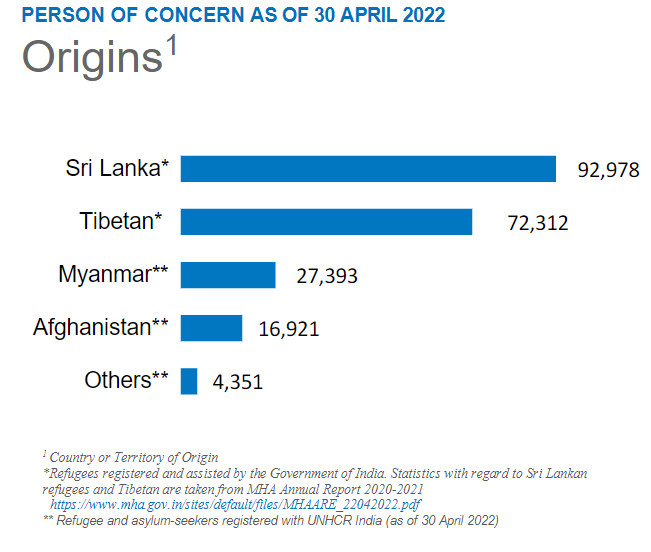

Further, the Act seems to operate vis-à-vis three Muslim-majority countries. However, India hosts a large number of refugees and migrants from other neighbouring countries also, particularly Myanmar, Nepal, China and Sri Lanka.[46]There has been no clarification rendered as to the rationale behind including only Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. Finally, unlike the cut-off date mentioned in the Assam Accord, the date of December 31, 2014 lacks rationale and therefore comes across as arbitrary. While the NRC process is already criticised for being exclusionary, the effect of NRC combined with the operation of provisions of the Citizenship Amendment Act seems to benefit the non-Muslim communities mentioned in the Act while disadvantaging the Muslim migrants whose names did not figure in the list. This essentially pushes the latter into a predicament of statelessness. It has to be noted here that this legislation is not merely discriminatory, but also wildly inconsistent with India’s obligations under International law.

India’s Approach to Statelessness in the Past

The outcome of NRC-CAA is not the first time India had to deal with the issue of statelessness. India has taken steps to mitigate the risks and consequences of statelessness in the past. The situation of enclave dwellers being a key example. Chittmahal or enclaves are pieces of land that belonged to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), yet remained in India, and vice versa. After the India-Pakistan partition in 1947 and the boundary limitations thenceforth, the enclave dwellers were essentially cut-off from access to their country of nationality as they were surrounded by foreign land, eventually pushing them into a state of de facto statelessness. Therefore, crossing borders for daily engagements became an illegal activity.[47] The hostility that ensued from the Partition reflected in the control of these enclaves. In the year 1952, both countries tightened visa policies, making their borders rigid. This trapped the enclave dwellers in a state of virtual lockdown.[48]Despite the sovereignty shift in 1971, with the creation of the independent nation state of Bangladesh, the plight of enclave dwellers remained unaddressed. On the other hand, the Bangladeshi enclave dwellers in India also lived under the constant fear of being arrested under the Foreigners Act of 1946.[49] The very first headcount in enclaves was conducted by state authorities only in the year 2011.[50] After decades of failed negotiations between India and Bangladesh, a Land-Boundary Agreement was finally implemented on 31 July 2015 at the Indo-Bangladesh border.[51] Despite this being a significant step towards progress, several scholars[52] have noted the continuity of the plight of erstwhile enclave-dwellers even after the Land-Boundary Agreement.[53] Since census had never been conducted in these area, the issue of identity crisis is quite prominent. Enclave dwellers are reported to own false voter ID cards and educational documents to “avoid becoming an illegal migrant”.[54] At this point, it is important to note the potential effects of an NRC process being implemented in the State of West Bengal (as promised by the ruling government) and its implications for enclave-dwellers. The identity crisis already existing within the enclaves, the errors in their identity cards, the threat of being suspected as a foreigner has been exacerbated by the looming NRC-CAA process.[55]

Another group of people that was forced to face the plight of statelessness due to the post-colonial repercussions, are the Hill Tamils from Sri Lanka. The Shrimavo-Shastri Pact of 1964 and the subsequent Shrimavo- Gandhi Pact 1974 were significant steps taken towards addressing the problems of the Hill Tamils.[56] However, there are a group of Hill Tamils who are stateless or at a risk of becoming stateless in India. The change in legislation in Sri Lanka, their displacement to India and their lack of birth registration and documentation has continued to add to their plight.[57] Despite qualifying for citizenship by naturalization under Sec.5 of the Citizenship Act, the fact that the Amendment Act has overlooked the plight of Hill Tamils is disappointing.[58]

In 1964, owing to the construction of the Kaptai hydroelectric project over the river Karnaphuli, the Chakmas and Hajongs were displaced and forced to migrate to India from the Chittagong Hill Tracts of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).[59] Although the Indian government encouraged them to settle in the Area of North East Frontier Agency (now Arunachal Pradesh), they have not been granted citizenship. With neither States claiming them as nationals, these indigenous people have essentially been pushed into a state of de jure statelessness. In the case of Committee for Citizenship Rights of the Chakmas of Arunachal Pradesh (CCRCAP) v The State of Arunachal Pradesh, the apex court upheld the rights of the Chakmas to be protected by the State of Arunachal Pradesh under Art. 21 of the Indian Constitution and also said that they “have a right to be granted citizenship subject to the procedure being followed”.[60]Now, the Citizenship Amendment Act would help in materialising the right to be granted citizenship of the Chakmas as upheld by the Supreme Court.

Just the fact that the CAA offers comfort and chaos respectively depending on the religious inclinations of the stateless populations in India, is a major red flag.

India has undeniably taken various steps towards protection of refugee populations and mitigating the risks of statelessness under several circumstances. In the year 1995, India also became a member of the UNHCR Executive Committee and has been playing an important part in reformulating international legal instruments concerning refugees and stateless persons. However, despite assuming such a pivotal position in the Executive Committee, the fact that India lacks a framework regulating the treatment meted out to refugees and stateless persons, thereby resulting in the absolute reliance of socio-politically motivated ad-hoc governmental policies, is worth criticising. Just the fact that the CAA offers comfort and chaos respectively depending on the religious inclinations of the stateless populations in India, is a major red flag.

International and National Legal Framework on Statelessness in India

The definition and standard of treatment for a Stateless person is enumerated in the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons.[61] This convention is the most comprehensive codification of the rights of stateless persons yet. It seeks to ensure the fundamental human rights of a person and freedom from discrimination against stateless persons. Although the Convention does not entitle a stateless person to acquire the nationality of a specific state, it does require state parties to take steps towards facilitating their naturalization and integration.[62] On the other hand, the 1961 Convention on Reduction of Statelessness provides a directive to States for the prevention and reduction of statelessness.[63] However, as India is a party to neither conventions, as in the case of refugees, we are left to resort to other international human rights instruments that India has signed and ratified.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, although a non-binding instrument, has been recognised for contributing to customary international human rights. Art. 15 of the UDHR provides that ‘everyone has the right to a nationality’[64] and that ‘no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality’.[65] Although the principles enshrined under the UDHR are not legally binding, it is pertinent to note that the CAA directly contravenes the right to nationality mentioned above. Further, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966 mandates the parties to the convention to ensure that the rights recognized in the Covenant be upheld without any discrimination of any kind in terms of race, colour, sex, language, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.[66] The Convention also guarantees the right of every child to acquire a nationality.[67]The Convention provides that State parties must ensure the protection of the rights of stateless people, without discrimination including under the law.[68] Despite having acceded to the Convention on April 10, 1979, by virtue of enacting the Citizenship Amendment Act and the operational effects of the NRC process combined with the Act is in clear violation of India’s obligations under the ICCPR.

Art. 12(4) of the ICCPR can be used particularly in favour of India’s obligations to protect stateless persons. Art. 12(4) states that, ‘No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of the right to enter his own country’. The phrase ‘no one’ under this provision allows scope for inclusion of nationals and aliens within its ambit. Therefore, we ought to analyse the phrase ‘own country’ in order to determine the beneficiaries of this provision. The General Comments of the Human Rights Committee remain the most authoritative interpretation of the ICCPR that is available to State Parties. With regard to Art. 12(4) of the Covenant, the General Comment reiterates that the phrase ‘own country’ does not refer to the concept of nationality alone. It also includes individuals who by virtue of their special ties or claims in relation to a given country, cannot be considered an alien.[69]The General Comment specifically mentions that this interpretation is to be applied in case where nationals of a country are stripped of their nationality in violation of international law.[70] It also states that the interpretation of Art. 12(4) might be read to include with its scope, ‘stateless persons arbitrarily deprived of the right to acquire the nationality of the country of such residence’.[71] In order to understand the concept of special ties and claims as mentioned in the General Comment on Art. 12(4), we may also refer to the concept of ‘genuine and effective link’ as dealt by the International Court of Justice in the Nottebohm Case.[72] The ICJ upheld that although different factors are taken into consideration in every case, the elements of “habitual residence of the individual concerned”, “the centre of his interests” i.e. “his family ties, his participation in public life, attachment shown by him for a given country and inculcated in his children, etc.”[73] are significant in determining a “genuine and effective link” between the individual and the State in question. In India, the people who are facing or at a risk of facing the plight of statelessness are long term residents in India who may be both religiously and ethnically similar to Indian communities and therefore maintain a socio-cultural relationship with India.[74] Under such circumstances, the individuals in question evidently qualify for protection from arbitrary deprivation of the right to enter their own country (India), under Art. Art. 12(4) of the ICCPR.

Further, by denying citizenship or nationality to people based on religion, India risks effectively excluding stateless persons from the loop of human rights itself. This also goes on to violate India’s commitments under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966. Besides Section 3 of the Indian Citizenship Act[75] which deprives a child Indian citizenship by birth in case of either of his parents being an illegal immigrant, the NRC process has also rendered several children Stateless. This violates India’s obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of a Child (CRC), to which India has acceded. Article 7 of the Convention mandates state parties to provide nationality to the children immediately after birth.[76]Thus, the Indian citizenship policy runs contrary to a number of international legal obligations of India. Article 51(c) of the Indian Constitution mandates the government to foster respect for international law and treaty obligations.

Despite the very evident gap in India’s legal framework on statelessness, Indian Courts have not dealt with the issue in detail. Nevertheless, the Courts have taken innovative approaches to avoid the occurrence of statelessness by applying principles of equity and justice.[77] In the case of Namgyal Dolkar vs. Government of India[78], in 2011, the Delhi High Court upheld, as per Sec.3 of the Citizenship Act that people born in India cannot be denied citizenship and the right to nationality based on their description in the identity certificate. In the case of Sheikh Abdul Aziz vs. NCT of Delhi[79], a ‘foreigner’ in India was detained in Kashmir for entering the country illegally. He was later shifted to the Tihar Central Jail to await deportation proceedings. The deportation proceedings were not executed for several years. In the year 2014, on the basis of the Delhi High Court’s direction to identify the nationality of the Individual, the state identified him to be stateless. Consequently, the State declared that the petitioner could approach the passport office to acquire identification papers and thereby apply for a long-term visa later on.[80] While this case indicates the role of Indian judiciary in identifying and providing relief to stateless persons, it also serves as an illustration of the attitude of the State towards stateless persons. This can be alluded to the fact that a concrete legal framework or mechanism to deal with stateless persons and the data and awareness on stateless persons is practically non-existent. The impact of such lacuna is also evident in the NRC-CAA process in Assam.

Plight of Stateless People in Assam

Although the Indian Ministry of External Affairs has communicated that the people excluded from the final draft of NRC would not be put in detention centres until their case is decided by the Foreigners Tribunal[81], the future of people whose cases are rejected by the Tribunal has been left mysteriously evaded. The Detention centres in Assam were originally intended for short-term detention of undocumented immigrants. In the case of Harsh Mander vs. Union of India[82], the Supreme Court of India dealt with important legal questions on the condition of detention centres and indefinite detention of ‘foreigners’. The government of Assam presented a plan to secure the monitored release foreigners who had been in detention centres more than five years on paying a hefty deposit and signing a bond. Ironically, this case which was filed to draw the attention of the apex court to the inhumane conditions in detention centres in Assam, turned into exhortation[83] to the government to work proactively on deporting individuals.[84] Although India does not have any legislation to protect stateless people from being deported to regularise their status or grant them citizenship, it does have legislation in place to deport illegal migrants. The Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunal) Act 1983, which gave the migrants a right to appeal and placed the burden of proof on the government was declared ultra vires by the Supreme Court of India in 2005 and is no longer valid.[85] In the Harsh Mander case, the Supreme Court directed “the Union of India to enter into necessary discussions with the Government of Bangladesh to streamline the procedure of deportation”[86]. Deportation, however, is not a unilateral exercise. Such processes usually follow negotiations and bilateral agreements for the readmission of nations of relevant country.[87] There has been no documented of India entering into diplomatic talks with Bangladesh regarding the issue of statelessness. Also, as recently as October 2017, it has been reported that the Bangladesh Information Minister, Hasanull Haq Inu denied any unauthorised migration from Bangladesh to Assam in the past 30 years.[88] According to the data produced before the Parliament, over 117,000 people have been declared foreigners by the Foreigners Tribunal in Assam up to March 31, 2019, of whom only four have been deported until now. Across the six detention centres in Goalpara, Kokrajhar, Silchar, Dibrugarh, Jorhat and Tezpur in Assam, 1005 people reportedly remain jailed according to the data produced before the Assam Legislative Assembly on July 29, 2019.[89] As detention camps are located within the jail premises, persons marked as illegal immigrants are locked up along with those jailed for criminal offences or who are undertrial. The country’s largest detention camp in the Goalpara district of western Assam, in addition to 10 proposed camps in the state.[90] In the case of P. Ulaganathan vs. The Government of India[91], the Madras High Court deciding on a case concerning the plight of Sri Lankan Hill Tamils in India who have been held in detention camps for about 35 years, upheld that, “keeping them under surveillance and severely restricted conditions and in a state of statelessness for such a long period certainly offends their rights under Article 21 of the Constitution of India”.[92] In the absence of any bilateral agreement dealing with deportation of the stateless persons who are allegedly Bangladeshi nationals, the detention of illegal immigrants seems short-sighted and ill-planned. Additionally, the lack of adequate documentation also makes it unlikely for the individuals to be deported to neighbouring countries in the near future. In addition to the apex court’s ratio in the P. Ulaganathan case on long periods of detention of stateless people, such an indefinite period of detention also violates India’s obligations under the ICCPR to uphold right to life,[93]right to dignity in detention[94] and the right against arbitrary deprivation of the right to enter his own country.[95]In their Guidelines on the Applicable Criteria and Standards relating to the Detention of Asylum-Seekers and Alternatives to Detention, the UN High Commissioner on Refugees emphasize the importance of setting a definite period of detention. The Guideline states that, without a cap on the period of detention, it can become prolonged and indefinite, especially for stateless asylum-seekers.[96] In the absence of any legal regulation of detention of the people who are rendered stateless in India, the UNHCR guidelines on detention might serve as a good starting point. Although the guidelines explicitly state that they only apply to asylum seekers and stateless persons who are seeking asylum, it also states that the standards enshrined therein may apply mutatis mutandis to others as well.[97]

Conclusion: The Way Forward

Customary international law has placed certain limitations on a state’s power of conferment of citizenship. Article 1 of the Hague Convention 1930, states that “it is for each state to determine under its own law who are its nationals. This law shall be recognised by other states in so far as it is consistent with international conventions, International custom, and the principles of law generally recognised with regard to nationality”.[98] As explained above, this is not the case with regard to the NRC-CAA process in India. Firstly, in order to deal with the problem of statelessness in India, it is absolutely necessary to identify and acknowledge the gravity of it. The data on the number of stateless persons in India is practically non-existent. It is important for the government to undertake efforts to facilitate data collection on stateless persons in India. This would not only help in mapping the extent of the problem, but it would also facilitate legal professionals, researchers, humanitarian works and practitioners to reach out and offer help where necessary.

Also, the presence of half-information and non-existence on specific data on the number of stateless persons and government policies vis-à-vis their treatment has allowed room for over-reliance on media sources and resulting confusion and frenzy. It might be important for the government to establish information hubs accessible to the common public to demystify data on statelessness and the rights that stateless persons are entitled to in India. A database of legal professionals, human rights activists and government representatives should be available in all such places. This would go a long way in reducing unlawful and illegal detention. It would also force the government into exercising transparency in their detention policies.

the combined effect of NRC and the Citizenship Amendment Act seems to be exclusionary and discriminatory. The Act is violative of the Indian constitutional principles and India’s international legal obligations.

The absolute lack of a national and international legal framework on statelessness operating in India is a major drawback. While the rights enshrined under the international bill of human rights and other human rights instruments that India is a party to may be referred, it is not sufficient to fill the lacuna. This absence of a concrete legal framework may leave room for adverse predicaments such as arbitrary detention, human rights abuses, trafficking and forced displacement. Especially considering the number of people who have been disenfranchised by the latest draft of the NRC, the need for a law promising the basic human rights of the people who are rendered stateless is dire. India has also abstained from ratifying the First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR 1976 and has thereby denied its people the access to the Individual Complaints Mechanism of the UNHRC. The International Court of Justice which is also vested with the power to address ICCPR violations, cannot investigate into the issue of India’s discriminatory and exclusionary Citizenship law as it is a sovereign act of the State.[99] Without the same being disputed by one or more States, the ICJ cannot exercise its power in this case.[100]

Finally, as explained above, the combined effect of NRC and the Citizenship Amendment Act seems to be exclusionary and discriminatory. The Act is violative of the Indian constitutional principles and India’s international legal obligations. While reviewing the purpose and objective of the Citizenship Amendment Act is important, it is also important for the government to undertake negotiations with the Bangladesh government on the plight of the people who would soon be stateless. The indefinite detention of “foreigners” without a long-term plan in place, would result in grave human rights violations and would also be an expensive affair for India.

Image Credit: opiniojuris.org

Notes

[1] See generally IOM, WORLD MIGRATION REPORT 2020 (IOM, Geneva, 2019), available at https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf , [accessed on 15 Feb 2020].

[2] See generally Emmanuel Kalechi Iwuagwu, The Concept of Citizenship: Its Application and Denial in the Contemporary Nigerian Society, INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES, Vol. 8 No. 1.

[3] Seyla Benhabib, THE RIGHTS OF OTHERS – ALIENS, RESIDENTS AND CITIZENS, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004) P. 49-52

[4] Ibid at P. 49

[5] Ibid at P. 49, 50

[6] Art. 1, Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, 1954.

[7] David Owen, On the Right to Have Nationality Rights: Statelessness, Citizenship and Human Rights, NETHERLANDS INTERNATIONAL LAW REVIEW 2018, (65), P. 301.

[8] Supra note 1, P. 47.

[9] Lily Chen et al, UNHCR Statistical Reporting on Statelessness, UNHCR STATISTICS TECHNICAL SERIES 2019, available at https://www.unhcr.org/5d9e182e7.pdf, [accessed on 17 Feb 2020].

[10] See generally Nafees Ahmad, The Right to Nationality and the Reduction of Statelessness- The Responses of the International Migration Law Framework, GRONINGEN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW, Vol. 5 No. 1.

[11] UNHCR, “This is our Home”- Stateless Minorities and their search for citizenship, UNHCR STATELESSNESS REPORT 2017, available athttps://www.unhcr.org/ibelong/wp-content/uploads/UNHCR_EN2_2017IBELONG_Report_ePub.pdf, P. 1, [accessed on 17 Feb 2020].

[12] Ibid

[13] Mathew J. Gibney, Denationalization and Discrimination, JOURNAL OF ETHNIC AND MIGRATION STUDIES 2019, available at https://doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1561065 [accessed on 17 Feb 2020].

[14] Antje Ellermann, Discrimination in Migration and Citizenship, JOURNAL OF ETHNIC AND MIGRATION STUDIES 2019, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1561053?needAccess=true, P. 7, [accessed on 17 Feb 2020].

[15] Human Rights Watch, India: Citizenship Bill Discriminates Against Muslims, (11 Dec, 2019), available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/12/11/india-citizenship-bill-discriminates-against-muslims, [accessed on 18 Feb 2020].

[16]OHCHR, Press briefing on India, (13 Dec, 2019), available at https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25425&LangID=E, [accessed on 18 Feb 2020].

[17] USCIRF, USCIRF Raises Serious Concerns and Eyes Sanctions Recommendations for Citizenship Amendment Bill in India, Which Passed Lower House Today, (09 Dec, 2019), available at https://www.uscirf.gov/news-room/press-releases-statements/uscirf-raises-serious-concerns-and-eyes-sanctions, [accessed on 18 Feb 2020].

[18] Manogya Loiwal, India Today, Assam NRC and BJP’s challenge: The votebank politics of NRC, (31 Aug, 2019), available at https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/assam-nrc-bjp-challenge-votebank-politics-1593711-2019-08-31, [accessed on 18 Feb 2020].

[19]All Assam Students Union (AASU) and All Assam Gan Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) were the major groups involved in this movement.

[20] Sanjay Barbora, National Register of Citizens: Politics and Problems in Assam, E-JOURNAL OF THE INDIAN SOCIOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2019, (3)2, available at http://app.insoso.org/ISS_journal/Repository/Article_NRC.pdf, P. 14, [accessed on 19 Feb 2020].

[21]Harrison Akins, The Religious Freedom Implications of the National Register of Citizens in India, USCIRF ISSUE BRIEF:INDIA 2019, available at https://www.uscirf.gov/sites/default/files/2019%20India%20Issue%20Brief%20- %20Religious%20Freedom%20Implications.pdf, P.1, [accessed on 19 Feb 2020].

[22] Ibid at P.2.

[23] Assam Accord, Clause 5.8, available at https://assamaccord.assam.gov.in/portlets/assam-accord-and-its-clauses, [accessed on 19 Feb 2020].

[24] Assam Public Works v Union of India and Ors. [Writ Petition (Civil) No. 274 of 2009]

[25] Alok Prasanna Kumar, National Register of Citizens and the Supreme Court, LAW & SOCIETY 2018, (53)29, available at https://www.academia.edu/37909102/National_Register_of_Citizens_and_the_Supreme_Court, P. 11, [accessed on 19 Feb 2020].

[26]Tora Agarwala, The Indian Express, Assam Citizenship List: Names missing in NRC final draft, 40 ;akh ask what next, (30 Jul 2018), available at https://indianexpress.com/article/north-east-india/assam/assam-citizenship-list-names-missing-in-nrc-final-draft-40-lakh-ask-what-next-5283663/, [accessed on 20 Feb 2020].

[27] Amit Ranjan, Assam’s National Register of Citizenship: Background, Process and Impact of the Final Draft, ISAS WORKING PAPER 2018, No. 306, available at https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/ISAS-Working-Papers-No.-306-Assams-National-Register-of-Citizenship.pdf, P.2, [accessed on 20 Feb 2020].

[28] Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty, The Wire, Both the BJP and the Trinamool Congress are Stirring the Communal Pot in Assam, (05 Aug 2018), available at https://thewire.in/politics/bjp-tmc-nrc-assam-communalism

[29] Supra note 27, [accessed on 20 Feb 2020].

[30]Abhishek Saha, The Indian Express, Assam NRC List: No person will be referred to Foreiners’ Tribunal or sent to detention centre based on final draft, (30 Jul 2018), https://indianexpress.com/article/north-eastindia/assam/assam-nrc-list-final-draft-foreigners-tribunal-detention-centre-5282652/, [accessed on 20 Feb 2020].

[31] Ditilekha Sharma, Determination of Citizenship through Lineage in the Assam NRC is Inherently Exclusionary, ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL WEEKLY, Apr 2019, available at https://www.epw.in/node/154137/pdf, [accessed on 20 Feb 2020].

[32] Angshuman Choudhury, National Register of Citizens (NRC): A Synonym for Deep Anxiety, THE CITIZEN , 2019, available at https://www.academia.edu/40257016/National_Register_of_Citizens_NRC_A_Synonym_for_Deep_Anxiety, P. 3, [accessed on 20 Feb 2020].

[33] Anusaleh Shariff, ‘National Register of Indian Citizens’ (NRIC) – Does the Assam Experience help Mainland States?, ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL WEEKLY, 2019, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337366837_’National_Register_of_Indian_Citizens’_NRIC_-_Does_the_Assam_Experience_help_Mainland_States, P. 18, [accessed on 20 Feb 2020].

[34] Supra note 27 at P. 8-11.

[35] The Citizenship Act 1955, No.57 of 1955, Sec. 2(1) (b).

[36] The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, No. 47 of 2019, Sec. 2.

[37] The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, No. 47 of 2019, Sec. 6.

[38] Narendar Nagarwal, Global Implications of India’s Citizenship Amendment Act 2019, (Jan 2020), available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338673204_Global_Implications_of_India’s_Citizenship_Amendment_Act_2019, P. 3, [accessed on 2 Mar 2020].

[39] Human Rights Watch, “We are the Walking Dead” – Killings of Shia Hazara in Balochistan, Pakistan, Jun 2014, available athttps://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/pakistan0614_ForUplaod.pdf, [accessed on 2 Mar 2020].

[40] Anon, The State of Minorities in Afghanistan, SOUTH ASIA STATE OF MINORITIES REPORT 2018, available at http://www.misaal.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/afghanistan.pdf, P. 282, [accessed on 2 Mar 2020].

[41] Human Rights Watch, “We can Torture, Kill, or Keep Your for Years” – Enforced Disappearances by Pakistam Security Forces in Balochistan, Jul 2011, available at https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/pakistan0711WebInside.pdf, [accessed on 2 Mar 2020].

[42]UK: Home Office, Country of Origin Information Report, Aug 2019, available at https://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?page=search&docid=5209feb94&skip=0&query=Ahmediyas%20&coi=PAK, P. 142, [accessed on 2 Mar 2020].

[43] Human Rights Watch, History of the Ahmadiyya Community, n.d., available at https://www.hrw.org/reports/2005/bangladesh0605/3.htm, [accessed on 2 Mar 2020].

[44] The Law of Return, 1950 in Israel established Israel as Jewish State based on the Zionist Philosophy which is also reflected in their citizenship policies.

[45] Keshavananda Bharati v State of Kerela, AIR 1973 SC 1461

[46] Supra note 38.

[47] Deboleena Sengupta, What Makes A Citizen: Everyday Life in India-Bangladesh Enclaves, ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL WEEKLY (53), 15 Sep 2018, available at https://www.epw.in/engage/article/chhit-spaces-a-look-at-life-and-citizenship-in-india-bangladesh-enclaves [accessed on 17 Mar 2020].

[48] Prachi Lohia, Forum Asia, Erstwhile enclaves in India: A post-LBA Analysis, 10 Dec 2019, available at https://www.forum-asia.org/uploads/wp/2019/12/Enclave-Report-Final-2.pdf, P. 7, [accessed on 17 Mar 2020].

[49] Ibid

[50] Ibid

[51] For the current state of erstwhile enclave-dwellers in India, see supra note 48 and also Prasun Chaudhari, The TelegraphThe same old story in Chittmahal, (12 May 2019), available at https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/the-same-old-story-in-chhitmahal/cid/1690343 [accessed on 17 Mar 2020].

[52] Supra note 48.

[53] Sreeparna Banerjee et al., The 2015 India-Bangladesh Land Boundary Agreement: Identifying Constraints and Exploring Possibilities in Cooh Behar, ORF OCCASIONAL PAPER, Jul 2017, P.5, available at https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/ORF_OccasionalPaper_117_LandBoundary.pdf [accessed on 17 Mar 2020].

[54] Ibid.

[55] Supra note 48, P. 45.

[56] V. Suryanarayanan, Challenge of Statelessness- The Indian Response, IIC Occasional Publication (88), , (n.d.), available at http://www.iicdelhi.nic.in/writereaddata/Publications/636694277561224320_Occasional%20Publication%2088.pdf, P. 3, [accessed on 17 Mar 2020].

[57] See UNHCR, Submission by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: UPR 27th Sessions, Aug 2016, available at https://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?page=search&docid=5a12b5420&skip=0&query=stateless&coi=IND, P. 2, [accessed on 17 Mar 2020].

[58] Supra note 56, P. 16.

[59] Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Executive Summary of the Report on ‘The State of Being Stateless: A Case Study of the Chakmas of Arunachal Pradesh, (n.d.), available at http://www.mcrg.ac.in/Statelessness.pdf [accessed on 17 Mar 2020].

[60] Committee for Citizenship Rights of the Chakmas of Arunachal Pradesh (CCRCAP) v The State of Arunachal Pradesh, [WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO.510 OF 2007]

[61] Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons 1954, Art. 1, 7.

[62] Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons 1954, Art. 32.

[63] See generally Convention on Reduction of Statelessness 1961.

[64] The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1945, Art. 15(1).

[65] The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1945, Art. 15(2).

[66] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, Art. 2.

[67] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, Art. 24

[68] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, Art. 26

[69] CCPR General Comment No. 27: Article 12(Freedom of Movement), (Nov 2, 1999), ¶ 20 available at https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/45139c394.pdf

[70] Ibid

[71] Supra note 69.

[72] Liechtenstein v. Guatemala (Nottebohm Case) 1955

[73] Ibid, Second Phase, Judgment, I.C.J. reports 1955, Rep 4.

[74] Unnati Ghia, Suddenly Stateless: International law Implications of India’s New Citizenship Law, OPINIO JURIS, Feb 5, 2020, available at http://opiniojuris.org/2020/02/05/suddenly-stateless-international-law-implications-of-indias-new-citizenship-law/ [accessed on 16 Mar 2020].

[75] The Citizenship Act, 1955, Act No. 57 of 1955, Sec. 3.

[76] Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989, Art. 7.

[77] Sitharamam Kakarala, India and the Challenge of Statelessness – A Review of the Legal Framework relating to Nationality, 2012, available at http://nludelhi.ac.in/download/publication/2015/India%20and%20the%20Challenges%20of%20Statelessness.pdf, P. 61, [accessed on 5 Mar 2020].

[78] Namgyal Dolkar vs. Government of India, [Writ Petition (Civil) 12179/2009]

[79] Sheikh Abdul Aziz v. NCT of Delhi, [Writ Petition (Criminal) 1426/2013]

[80] Aneesha Mathur, The Indian Express, ‘Stateless man’ to get visa, ID to stay in India, (29 May 2014), available at https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/stateless-man-to-get-visa-id-to-stay-in-india/, [accessed on 5 Mar 2020].

[81]Indian Ministry of External Affairs, Statement by MEA on National Register of Citizens in Assam, (02 Sep 2019), available at https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/31782/Statement+by+MEA+on+National+Register+of+Citizens+in+Assam, [accessed on 5 Mar 2020].

[82] Harsh Mander v Union of India, [Writ Petition (Civil) No.1045/2018].

[83] Colin Gonsalves, Human Rights Law Network, Stateless and Marginalised in Assam, (18 Sep 2019), available at https://hrln.org/reporting_publications/nrc-violates-constitutional-morality-principles-of-international-law/, [accessed on 6 Mar 2020].

[84] Supra note 82.

[85] Sarbananda Sonawal v. Union of India, [Writ Petition (civil) 131 of 2000]

[86] Supra note 82.

[87] See generally, the Shrimavo-Shastri Accord, 1964 (1992).

[88]Sanjib Baruah, The Indian Express, Stateless in Assam, (19 Jan 2018), available at https://epaper.indianexpress.com/c/25513604, [accessed on 10 Mar 2020].

[89]The Economic Times, 1.17 lakh people declared as foreigners by tribunals in Assam, (16 Jul 2019), available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/1-17-lakh-people-declared-as-foreigners-by-tribunals-in-assam/articleshow/70244101.cms?from=mdr, [accessed on 10 Mar 2020].

[90] Nazimuddin Siddique, Inside Assam’s Detention Camps: How the Current Citizenship Crisis Disenfranchises Indians, ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL WEEKLY (55)7, Feb 2020, available at https://www.epw.in/engage/article/inside-assams-detention-camps-how-current, [accessed on 10 Mar 2020].

[91] P.Ulaganathan vs The Government Of India, [Writ Petition (MD)No.5253 of 2009]

[92] Ibid

[93] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, Art. 6.

[94] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, Art. 10.

[95] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, Art. 12(4)

[96] UNHCR, Detention Guidelines – Guidelines on the Applicable Criteria and Standards relating to the Detention of Asylum-Seekers and Alternatives to Detention 2012, available at https://www.unhcr.org/publications/legal/505b10ee9/unhcr-detention-guidelines.html, P. 26, [accessed on 17 Mar 2020].

[97] Ibid, P. 8.

[98] Nafees Ahmad, The Right to Nationality and the Reduction of Statelessness – The Responses of the International Migration Law Framework, GRONINGEN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW (5)1, Sep 2017, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320244117_The_Right_to_Nationality_and_the_Reduction_of_Statelessness_-_The_Responses_of_the_International_Migration_Law_Framework, P. 3, [accessed on 16 Mar 2020].

[99] Supra note 74.

[100] International Court of Justice, Frequently Asked Questions, available at https://www.icj-cij.org/en/frequently-asked-questions , [accessed on 16 Mar 2020].