“A good navy is not a provocation to war. It is the surest guarantee of peace!”

The Indian Ocean has been at the centre of world history ever since we know it. Man originated in Africa, probably somewhere in the Olduvai Gorge in present-day Tanzania – where Homo Erectus lived 1.2 million years ago and where the first traces of Homo Sapiens, our more recent ancestors having evolved only about 200,000 years ago. First phonetic languages evolved around 100, 000 years ago. The migration of mankind out of Africa began almost 60000 years ago. But we don’t call the Indian Ocean the African Ocean because the first recorded activity over it began only about 3000 years ago.

Three great early recorded activities of this period come to mind. The first is the Indus Valley Civilization. It was a Bronze Age civilization (3300–1300 BCE; mature period 2600–1900 BCE) in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. Along with Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, it was one of three early civilizations of the Old World, and of the three the most widespread.

The Indus civilization’s economy appears to have depended significantly on trade, which was facilitated by major advances in transport technology. It may have been the first civilization to use wheeled transport. These advances may have included bullock carts that are identical to those seen throughout South Asia today, as well as boats. Most of these boats were probably small, flat-bottomed craft, perhaps driven by sail, similar to those one can see on the Indus River today; however, there is secondary evidence of sea-going craft.

Archaeologists have discovered a massive, dredged canal and what they regard as a docking facility at the coastal city of Lothal now in Gujarat. Judging from the dispersal of Indus civilization artifacts, the trade networks, economically, integrated a huge area, including portions of Afghanistan, the coastal regions of Persia, northern and western India, and Mesopotamia. There is some evidence that trade contacts extended to Crete and possibly to Egypt.

There was an extensive maritime trade network operating between the Harappan and Mesopotamian civilizations as early as the middle Harappan Phase, with much commerce being handled by “middlemen merchants from Dilmun” (modern Bahrain and Failaka located in the Persian Gulf). Such long-distance sea trade became feasible with the innovative development of plank-built watercraft, equipped with a single central mast supporting a sail of woven rushes or cloth.

The second great economic activity was Slavery. Slavery can be traced back to the earliest records, such as the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1760 BC), which refers to it as an established institution. Slavery is rare among hunter-gatherer populations, as it is developed as a system of social stratification. Slavery typically also requires a shortage of labour and a surplus of land to be viable. Bits and pieces from history indicate that Arabs enslaved over 150 million African people and at least 50 million from other parts of the world. Later they also converted Africans into Islam, causing a complete social and financial collapse of the entire African continent apart from wealth attributed to a few regional African kings who became wealthy in the trade and encouraged it.

The third great economic activity was seafaring evidenced by migration. The island of Madagascar, the largest in the Indian Ocean, lies some 250 miles (400 km) from Africa and 4000 miles (6400 km) from Indonesia. New findings, published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, show that the human inhabitants of Madagascar are unique – amazingly, half of their genetic lineages derive from settlers from the region of Borneo, with the other half from East Africa. It is believed that the migration from the Sunda Islands began around 200 BC.

Linguists have established that the origins of the language spoken in Madagascar, Malagasy, suggested Indonesian connections, because its closest relative is the Maanyan language, spoken in southern Borneo. The Gods were also kind and gave the IOR the weather conditions that helped in evolving seaborne trade and intercourse. The sea surface current and prevailing wind structure in and over the Indian Ocean favoured seafarers in their endeavour and sailings in the Indian Ocean from the southern tip of Africa (Cape of Good Hope) during the month of May. After the entry into the Indian Ocean, the seafarers continued to sail in the northerly direction along the coastline of Africa (aided by the strong Somali Current and the East Arabian Current) towards the Arabian Sea.

The physical environmental conditions over the sea and the external prevailing weather helped the seafarers reach places up to the west coast of India. As this sea surface current extend towards the east coast of India, the sailors were greatly assisted by the surface current as they sailed along. During November, when the East Indian Winter wind reverses in its direction and begins to blow from the northeast, the sailors prepare for their return journey. The winds that generate the waves contribute to the reduction in the otherwise required travel time for the sailings between any given two points of departure and arrival. The natural and external forces help the sailors make their journey/expedition more economical and energy-efficient.

Clearly, the region was a hub of all kinds of economic activity. Then came the Petroleum Age. And things changed as never before. The Spice trade, the Silk trade, and the China trade all paled into insignificance. The use of Coal as a ship fuel enlarged distances and volumes of cargo. Oil made even longer journeys and greater volumes possible.

Petroleum is the lifeblood of modern society. It’s a relatively new activity, but its advent has transformed our world as few things have. Petroleum, in one form or another, has been used since ancient times. According to Herodotus more than 4000 years ago, asphalt was used in the construction of the walls and towers of Babylon; there were oil pits near Babylon, and a pitch spring on Zacynthus.

Great quantities of it were found on the banks of the river Issus, one of the tributaries of the Euphrates. Ancient Persian tablets indicate the medicinal and lighting uses of petroleum in the upper levels of their society. By 347 AD, oil was produced from bamboo-drilled wells in China. Early British explorers to Myanmar documented a flourishing oil extraction industry based in Yenangyaung, that in 1795 had hundreds of hand-dug wells under production.

Oil is now the single most important driver of world economics, politics and technology. The rise in importance was due to the invention of the internal combustion engine, the rise in commercial aviation, and the importance of petroleum to industrial organic chemistry, particularly the synthesis of plastics, fertilizers, solvents, adhesives and pesticides. Today, oil contributes 3% of the global GDP.

In 1847, the process to distill kerosene from petroleum was invented by James Young. He noticed natural petroleum seepage in the Riddings colliery at Alfreton, Derbyshire from which he distilled a light thin oil suitable for use as lamp oil, at the same time obtaining a thicker oil suitable for lubricating machinery. In 1848 Young set up a small business refining the crude oil.

Today the world’s biggest stand-alone refinery is the Reliance refinery at Jamnagar with a refining capacity of about 1.5 million barrels a day. The Essar refinery at Jamnagar refines a further 0.5 million barrels a day. Together they make Jamnagar one of the world’s great refining centers. India’s number one export item is Petroleum products, mostly Petrol and Diesel. India now exports the equivalent of about

615,000 barrels a day. In 2020, petroleum exports accounted for $25.3 billion of our total exports of $291.8 billion in the same year.

India imported $77 billion worth of oil in the year 2020-21 and more than half of this comes from countries in the IOR. Iraq’s share is 22.4%, Saudi Arabia’s share is 18.8%, UAE’s share is 10.8%, and Kuwait’s 5%. The IOR is India’s lifeline and lifeblood. If the line is blocked we will suffer hugely, if the blood gets anaemic we will suffer hugely. India just cannot afford anything to go wrong here.

The sea lanes in the Indian Ocean are considered among the most strategically important in the world—according to the Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, more than 80 percent of the world’s seaborne trade in oil transits through the Indian Ocean choke points, with 40 percent passing through the Strait of Hormuz, 35 percent through the Strait of Malacca and 8 percent through the Bab el-Mandab Strait.

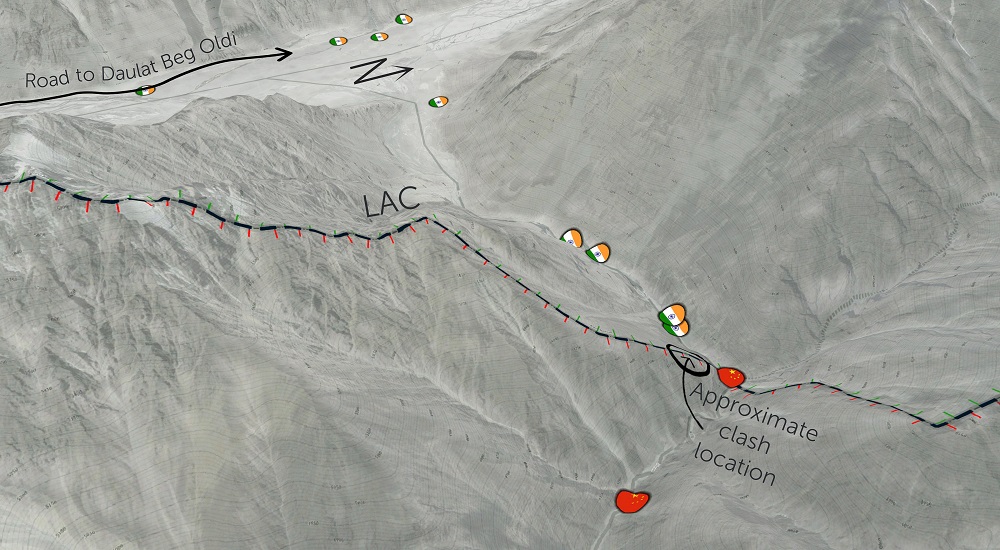

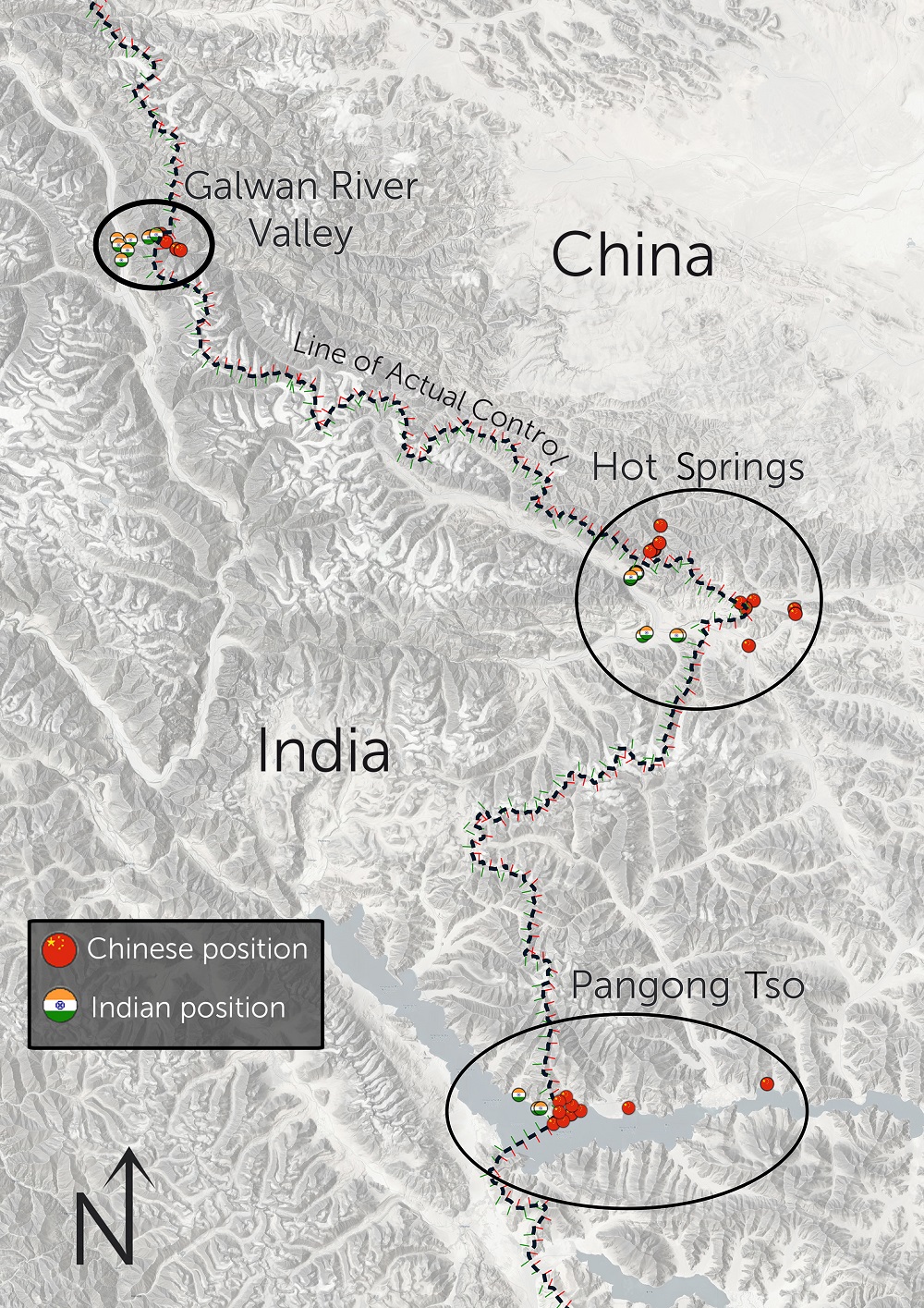

But it’s not just about sea-lanes and trade. More than half the world’s armed conflicts are presently located in the Indian Ocean region, while the waters are also home to continually evolving strategic developments including the competing rises of China and India, the potential nuclear confrontation between India and Pakistan, the US interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, Islamist terrorism, incidents of piracy in and around the Horn of Africa, and management of diminishing fishery resources.

As a result of all this, almost all the world’s major powers have deployed substantial military forces in the Indian Ocean region. For example, in addition to maintaining expeditionary forces in Iraq, the US 5th Fleet is headquartered in Bahrain, and uses the island of Diego Garcia as a major air-naval base and logistics hub for its Indian Ocean operations. In addition, the United States has deployed several major naval task forces there, including Combined Task Force 152 (currently operated by the Kuwait Navy), which is focusing on illicit non-state actors in the Arabian Gulf, and Combined Task Force 150 (currently commanded by the Pakistan Navy), which is tasked with Maritime Security Operations (MSO) outside the Arabian Gulf with an Area of Responsibility (AOR) covering the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Oman. France, meanwhile, is perhaps the last of the major European powers to maintain a significant presence in the north and southwest Indian Ocean quadrants, with naval bases in Djibouti, Reunion, and Abu Dhabi.

And, of course, China and India both also have genuine aspirations of developing blue water naval capabilities through the development and acquisition of aircraft carriers and an aggressive modernization and expansion programme.

China’s aggressive soft power diplomacy has widely been seen as arguably the most important element in shaping the Indian Ocean strategic environment, transforming the entire region’s dynamics. By providing large loans on generous repayment terms, investing in major infrastructure projects such as the building of roads, dams, ports, power plants, and railways, and offering military assistance and political support in the UN Security Council through its veto powers, China has secured considerable goodwill and influence among countries in the Indian Ocean region.

And the list of countries that are coming within China’s strategic orbit appears to be growing. Sri Lanka, which has seen China replace Japan as its largest donor, is a case in point—China was no doubt instrumental in ensuring that Sri Lanka was granted dialogue partner status in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

To the west, Kenya offers another example of how China has been bolstering its influence in the Indian Ocean. The shift was underscored in a leaked US diplomatic cable from February 2010 that was recently published by WikiLeaks. In it, US Ambassador to Kenya Michael Ranneberger highlighted the decline of US influence in East Africa’s economic hub, saying: ‘We expect China’s engagement in Kenya to continue growing given Kenya’s strategic location…If oil or gas is found in Kenya, this engagement will likely grow even faster. Kenya’s leadership may be tempted to move close to China in an effort to shield itself from Western, and principally US pressure to reform.’

The rise of China as the world’s greatest exporter, its largest manufacturing nation and its great economic appetite poses a new set of challenges. At a meeting of South-East Asian nations in 2010, China’s foreign minister Yang Jiechi, facing a barrage of complaints about his country’s behaviour in the region, blurted out the sort of thing polite leaders usually prefer to leave unsaid. “China is a big country,” he pointed out, “and other countries are small countries and that is just a fact.”

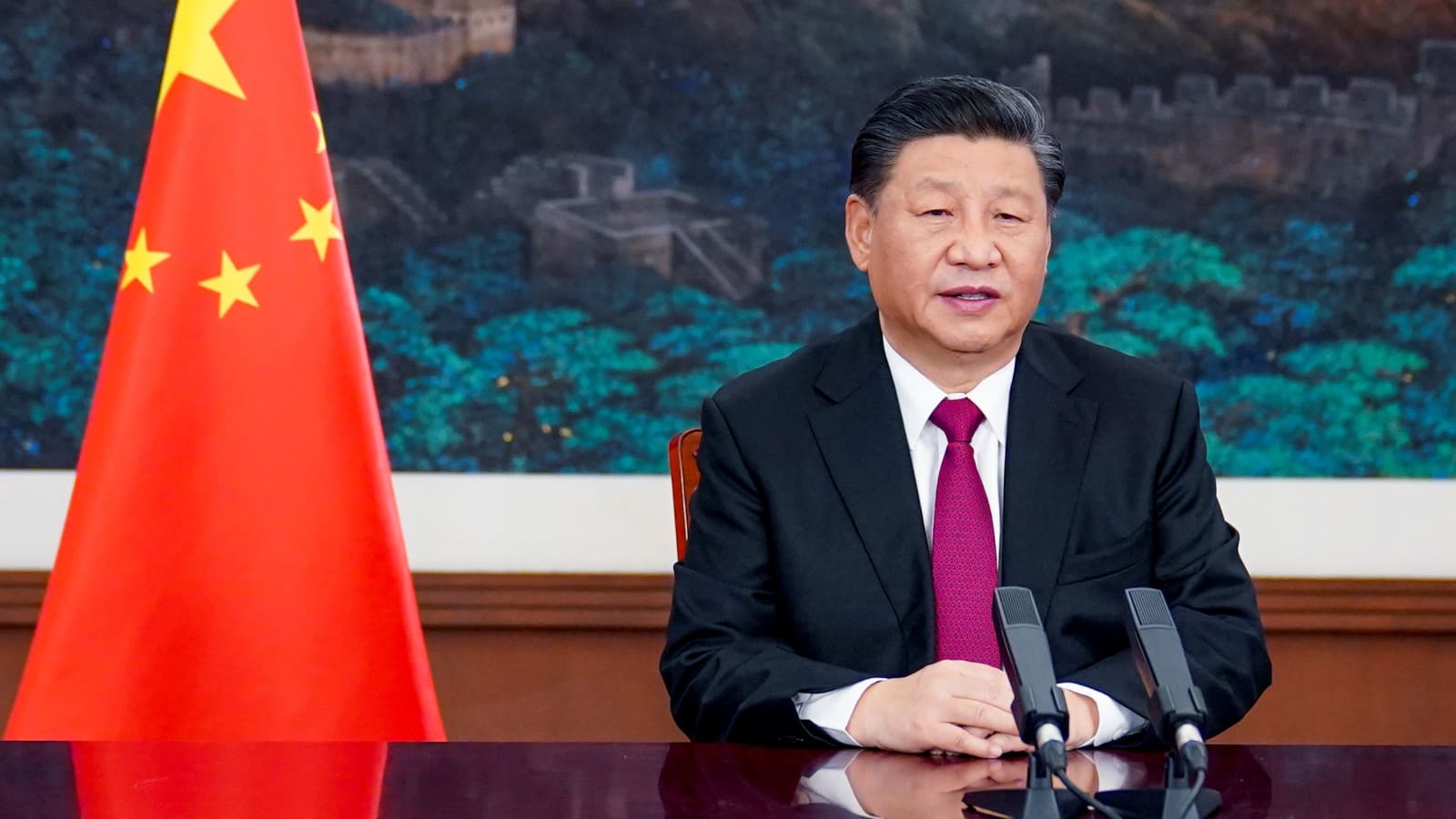

Indeed it is, and China is big not merely in terms of territory and population, but also in military might. Its Communist Party is presiding over the world’s largest military build-up. And that is just a fact, too—one that the rest of the world has to come to terms with.

China’s defence budget has almost certainly experienced double-digit growth for two decades. According to SIPRI, a research institute, annual defence spending rose from over $30 billion in 2000, $120 billion in 2010 to almost $229.4 billion in 2021. SIPRI usually adds about 50% to the official figure that China gives for its defence spending, because even basic military items such as research and development are kept off budget. Including those items would imply total military spending in 2021, based on the latest announcement from Beijing, would be around $287.8 billion.

This is not a sum India can match and the last thing we need to get caught in is a numbers game. A one-party dictatorship will always be able to outspend us, even if our GDPs get closer.

But history tells us again and again that victory is not assured by superiority in numbers and even technology. If that were to be so, Alexander should have been defeated at Gaugamela, Babur at Panipat, Wellington at Waterloo, Russia at Leningrad, Britain in the Falklands, and above all Vietnam who defeated three of the world’s leading powers – France, the USA and China – in succession. I don’t have to tell you that victory is more a result of strategy and tactics. Numbers do matter, but numbers are not all. Technology does matter, but technology alone cannot assure you of victory. It’s always mind over matter. You know these things better than most of us. You also know what to do. As the old saying goes: “When the going gets tough, the tough get going!”

That said, the threat from China should not be exaggerated. There are three limiting factors. First, unlike the former Soviet Union, China has a vital national interest in the stability of the global economic system. Its military leaders constantly stress that the development of what is still only a middle-income country with a lot of very poor people takes precedence over military ambition. The increase in its military spending reflects the growth of the economy, rather than an expanding share of national income. For many years China has steadily spent the same proportion of GDP on defence (a bit over 1.7%, whereas America spend about 3.7% in the year 2020-21).

The real test of China’s willingness to keep military spending constant will come when China’s headlong economic growth starts to slow further. But in the past form, China’s leaders will continue to worry more about internal threats to their control than external ones. In 2020, the Chinese spending on internal security was $212 billion. With a rapidly ageing population, it is also a good bet that meeting the demand for better health care will become a higher priority than maintaining military spending.

Like all the other great powers, China faces a choice of guns and butter or more appropriately walking sticks. But till then it is: Nervi belli pecunia infinita or unlimited money is the muscle of war.

India on the other hand will keep growing long after China has stopped growing. Its youthful population and present growth trends indicate the accumulation of the world’s largest middle class in India. India’s growth is projected to continue well past 2050. In fact so big will this become, that India during this period will increasingly power world economic growth, and not China. In 2050, India is projected to have a population of 1.64 billion and of these 1.3 billion will belong to the middle and upper classes. The lower classes will be constant at around 300 million, as it is now.

India already has the world’s third-largest GDP. Many economists prophesize that in 2050 it will be India that will be the world’s biggest economy, not China. In per capita terms, we might still be poorer, but in over GDP terms, we will be bigger.

According to a study by IHS Markit, a subsidiary of S&P Global, India will be the world’s third-largest economy by 2030. Indian GDP in 2030 is projected to be $8.4 trillion. China, in second place, will have a GDP of $ 33.7 trillion and the US $ 30.4 trillion. As we say in India, aap key muh mein ghee aur shakhar. Both incidentally now deemed bad for health.

Now comes the dilemma for India. Robert Kaplan writes: “As the United States and China become great power rivals, the direction in which India tilts could determine the course of geo-politics in Eurasia in the 21st century. India, in other words, looms at the ultimate pivot state.” At another time Mahan noted that India, located in the centre of the Indian Ocean littoral, is critical for the seaward penetration of both the Middle-east and China.

Now if one were an Indian planner, he or she would be looking at the China Pakistan axis with askance. India has had conflicts and still perceives threats from both, jointly and severally. The Tibetan desert, once intended to be India’s buffer against the north now has become China’s buffer against India. The planner will not be looking at all if he or she were not looking at the Indian Ocean as a theatre. After all, it is also China’s lifeline and its lifeblood flows here.

Now if one were a Chinese planner, he or she would be looking with concern over India’s growth and increasing ability to project power in the IOR. The planner will also note what experts are saying about India’s growth trajectory. That it will be growing long after China gets walking sticks. That it is the ultimate pivot state in the grand struggle for primacy between the West led by the USA and Japan, and China.

What will this planner be thinking particularly given the huge economic and military asymmetry between China and India now? Tacitus tells it most pithily. That peace can come through strength or Si vis pacem para bellum. While China has ratcheted up its show of assertiveness in recent years, India has been quietly preparing for a parity to prevent war. Often parity does not have to be equality in numbers. The fear of pain disproportionate to the possible gains, and the ability of the smaller in numbers side to do so in itself confer parity.

There is a certain equilibrium in Sino-Indian affairs that make recourse to force extremely improbable. Both modern states are inheritors of age-old traditions and the wisdom of the ages. Both now read their semaphores well and know how much of the sword must be unsheathed to send a message. This ability will ensure the swords remain recessed and for the plowshares to be out at work.

Finally, I would be remiss if I did not say something about the centrality of the Indian Navy to our future. Nothing says it better than what Theodore Roosevelt said a century ago: “A good Navy is not a provocation to war. It is the surest guarantee of peace!”

Featured Image Credit: Indian Navy