Democracy at its core is the power of the people. But all over the world, it is becoming anything but that. Truly the fear is that democracy is dying, as most nations that call themselves democracies are in effect controlled by capitalist oligarchs and majoritarian fascists. The power of money and vested interests have vitiated democratic processes worldwide. Michael Hudson calls the USA, once the beacon of democracy, a deep state controlled by three main oligarchic groups: Military Industrial Complex (MIC); Oil, Gas, and Mining (OGAM); and Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate (FIRE). Add the new emerging giant group – Big Tech – as the fourth. The UK, the world’s oldest parliamentary system, is in shambles as a democracy. India, seen as the world’s largest democracy, is heading the majoritarian way. Majoritarianism is not democracy but tyranny. This is what the Father of the Nation had to say about democracy at the height of the freedom struggle:

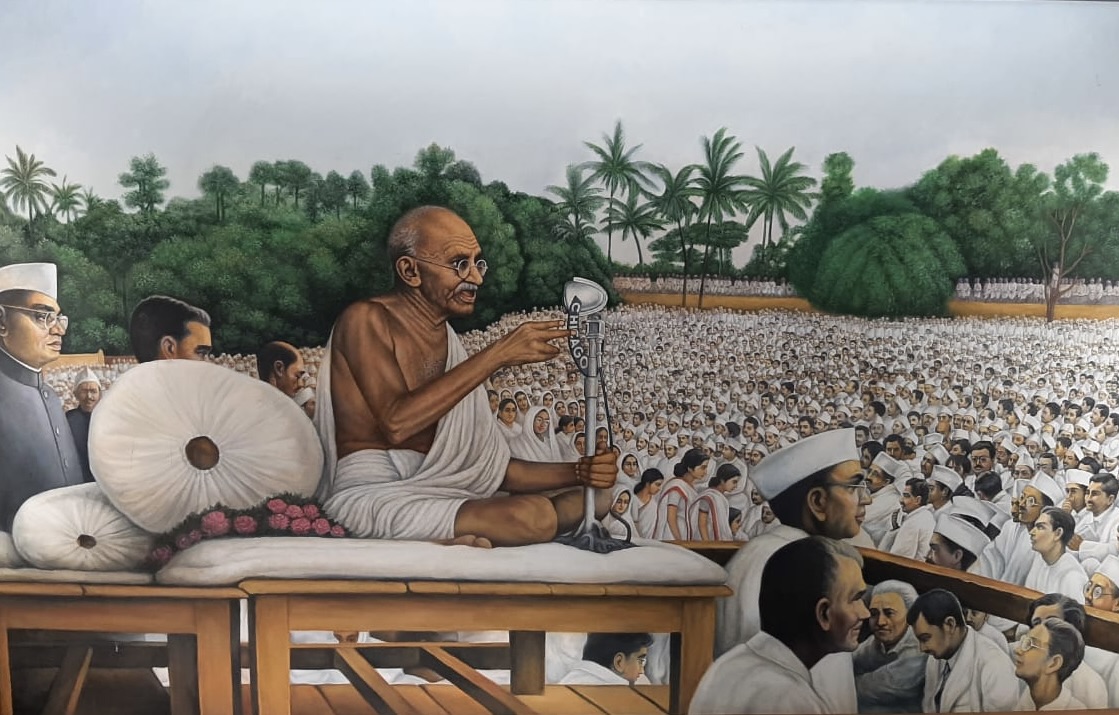

“My notion of democracy is that under it the weakest should have the same opportunity as the strongest….No country in the world today shows any but patronising regard for the weak….Western democracy, as it functions today, is diluted fascism….True democracy cannot be worked by twenty men sitting at the centre. It has to be worked from below by the people of every village.” – Mahatma Gandhi

His words could not have been more apt for the times we live in. This quote is placed in the Sabarmati Ashram. One wonders how many take a moment to stop by to read it carefully and take in the import of his words. The Mahatma is the shining example of personal integrity, character, and moral courage. Since democracy is primarily driven by people and politics, it is vital that those at the helm of governance display impeccable integrity to ensure real democracy.

Professor Arun Kumar PhD, an eminent economist and our adjunct Distinguished Fellow, writes eloquently on the subject and says ‘absence of persons with impeccable integrity is the bane of India’s democracy’. TPF is happy to republish this article.

A version of this article was published earlier in theleaflet.in

–TPF Editorial Team

Gandhiji said that institutions reflect what the people are, and that they cannot function as they are intended to unless those manning them are people of integrity.

A Supreme Court Constitution bench recently said that the Chief Election Commissioner should be one “with character” and who would not get “bulldozed” – a self-evident truth. Further, it suggested that the selection committee for the post should consist of an independent person like the Chief Justice of India (‘CJI’). It added that people and bureaucrats like the former Chief Election Commissioner late T.N. Seshan, who could act independently, “happen once in a while”.

Perhaps without meaning to, these comments indict the election commissioners appointed since Seshan’s time. Therefore, they have given voice to recent public concerns about the independence of the institution.

Integrity of Constitutional authorities

Will the CJI’s presence in the committee to appoint the Election Commissioners make a difference? The CJI is a member of the committee to appoint the Director of the Central Bureau of Investigation (‘CBI’). But the Supreme Court itself has called the CBI a “caged parrot”. The problem arises since the party in power would prefer a sympathetic person as an Election Commissioner, not an independent person.

The appointment of Supreme Court judges has become contentious, with the judges and the Union Law Minister currently at loggerheads. Judges themselves have talked of pressures and counter pressures from within and from the government. Appointments of some who are seen to be inconvenient have been withheld. Earlier this week, a division bench of the Supreme Court mentioned that by delaying appointments, good people are dissuaded from becoming judges. It is suspected that the appointment of certain judges is delayed so that they do not become CJI in due course of time. It appears that pliability is a desirable attribute to becoming a judge.

The Supreme Court, by raising the issue of the appointment of the Election Commissioner, has also brought into question the integrity of the Prime Minister (‘PM’), who is key to the appointment. Thus, doubt has been raised about the country’s constitutional authorities, including the judiciary. The executive, in any case, does the bidding of the political masters. So, where are the people of integrity in the corridors of power in India?

Defining integrity

Institutions can run as they ought to only if they are manned by people with integrity. Its absence from the top down is a societal challenge. Mahatma Gandhi in ‘Hind Swaraj’ (Indian Home Rule), more than a century back, said, “As are the people, so is their Parliament.” Since the Parliament is key to the functioning of a democracy, this flaw afflicts institutions down the line.

PMs heading the government are political persons. Since politics is about power, they try everything to keep themselves and their party in power. Their election depends on the support of vested interests who fund both them and their party and therefore, dominate the working of the party. So, staying in power is a high stake business which requires manipulation of the systems in their favour.

The Supreme Court, by raising the issue of appointment of the Election Commissioner, has brought into question the integrity of the Prime Minister, who is key to the appointment. Thus, doubt has been raised about the country’s constitutional authorities, including the judiciary.

There is then a separation of the interest of the nation, and of the party and its head, the PM. Consequently, for the party, integrity means that which serves its interest, which is not necessarily what the nation needs. This separation is what Gandhi implies in Hind Swaraj. No wonder, it is only a rare PM who has the moral integrity to select independent people for important Constitutional positions like the Election Commission and the judiciary.

Politicians go through years of such conditioning before becoming PMs and it becomes their second nature. It cannot be expected to change upon becoming the PM. The opposition in a democracy is supposed to check the misuse of power. But the leaders of the opposition also go through the same conditioning as leaders of the ruling party and therefore, act no differently. Politicians often pride themselves on managing conflicts by making compromises and accepting the manipulation of power. So, politicians take a pliable stand, based on the chair they occupy – in power or out of it.

Gandhi on parliamentary democracy

Gandhi, commenting on the British Parliamentary democracy in Hind Swaraj, wrote, “The Prime Minister is more concerned about his power than about the welfare of Parliament … [and] upon securing the success of his party.” He added that they may be considered to be honest “because they do not take what is generally known as bribes… [but] …they certainly bribe the people with honours.” Therefore, “… they neither have real honesty nor a living conscience”.

Regarding the Members of Parliament who could keep the PM in check, he wrote, “… Members are hypocritical and selfish. Each thinks of his own little interest. … Members vote for their party without a thought.” Regarding the media, another institution that could help check misuse of public authority by creating public awareness, he wrote that they “are often dishonest. The same fact is differently interpreted … according to the party in whose interest they are edited.” Gandhi was also scathing about the legal profession when he wrote, “… the profession teaches immorality …”.

Gandhi was pointing to the fundamental flaws in the functioning of democracies. It also applies in the current Indian context. He was pointing to weak public accountability of those in power since public awareness was low. The public has little choice but to accept the existing imperfect political system. The British Parliamentary democracy may be the best available system, but it is highly flawed and its defects appear more starkly in weak democracies like that in India.

We may be called the largest democracy in the world and we have succeeded in preserving it in the last 75 years, but it is frayed, as made clear by the current political problems facing us.

Feudal attitudes and democracy

Indian democracy’s weakness is a result of the persistence of feudal consciousness among a majority who easily accept authority. This is true even in institutions of higher education, where people are expected to be the most conscious. Most of these institutions are headed by academics with a bureaucratised mindset, who expect compliance and treat dissent as a malaise to be eradicated. In turn, they yield to politicians and bureaucrats.

A feudal system has its own concept of integrity. The ruler’s interest is broadly the nation’s interest. This congruity breaks in a parliamentary democracy where the consciousness is feudal. In such a case, integrity as defined by national interest is likely to be subverted, as is visible in India.

In 1947, India with its feudal consciousness ingrained and copied parliamentary democracy, not because people were ready for it, but because the leadership desired it since they wanted to copy Western modernity. People blindly accepted it since it came from their leaders, not because they understood it. Liberality at the top frayed post mid-1960s, as retaining power became more difficult and leaders turned increasingly authoritarian. So, while retaining the façade of democracy, it increasingly got hollowed out.

In 1947, India with its feudal consciousness ingrained and copied parliamentary democracy, not because people were ready for it, but because the leadership desired it since they wanted to copy Western modernity. People blindly accepted it since it came from their leaders, not because they understood it.

The political economy also pushed policies that marginalised the majority in the interest of the few. The black economy grew rapidly, making elections formalistic and draining them of their representational character. Most importantly, the rulers realized that neither the people ask for liberality nor do they demand accountability from leadership.

Need for accountability at the top

Accountability has to come from the top, whether in politics or in the government or the courts. It is not going to automatically come about without public pressure. A few freebies are enough to divert public attention. So, is accountability a luxury when basic issues are many?

The lack of integrity in public life is costly. The nation’s energy is diverted. Reforms favouring the marginalised are circumvented. Laws are framed ostensibly to improve matters, but when the spirit is not willing they fail to deliver. Perfect laws are not possible, since human ingenuity can circumvent any law. The result is more complex laws and growing cynicism.

What Gandhi pointed out is playing itself out in India. He said institutions reflect what the people are, and that they cannot function as they are intended to unless those manning them are people of integrity. But, can people with integrity emerge when it is missing all around, feudal consciousness pervades and people bend to authority?

Reform requires us to resolve the contradiction between parliamentary democracy and the prevailing feudal consciousness. This cannot happen from above. It requires the transformation of the people’s consciousness – Gandhi’s unfinished agenda.

Opinions expressed are those of the author.