Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a ubiquitous presence in our daily lives, transforming the way we operate in the modern era. From the development of autonomous vehicles to facilitating advanced healthcare research, AI has enabled the creation of groundbreaking solutions that were once thought to be unattainable. As more investment is made in this area and more data becomes available, it is expected that AI will become even more powerful in the coming years.

AI, often referred to as the pursuit of creating machines capable of exhibiting intelligent behaviour, has a rich history that dates back to the mid-20th century. During this time, pioneers such as Alan Turing laid the conceptual foundations for AI. The journey of AI has been marked by a series of intermittent breakthroughs, periods of disillusionment, and remarkable leaps forward. It has also been a subject of much discussion over the past decade, and this trend is expected to continue in the years to come.

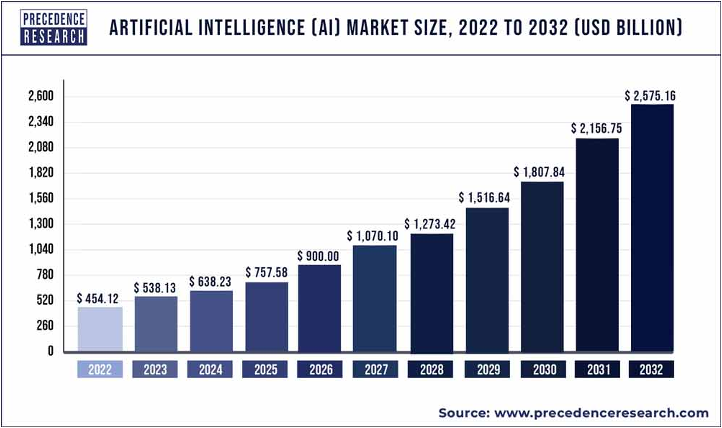

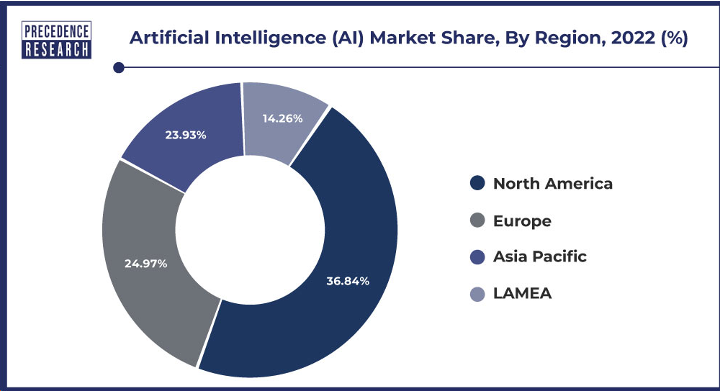

According to a report by Precedence Research, the global artificial intelligence market was valued at USD 454.12 billion in 2022 and is expected to hit around USD 2,575.16 billion by 2032, progressing with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 19% from 2023 to 2032. The Asia Pacific is expected to be the fastest-growing artificial intelligence market during the forecast period, expanding at the highest CAGR of 20.3% from 2023 to 2032. The rising investments by various organisations towards adopting artificial intelligence are boosting the demand for artificial intelligence technology.[1]

Figure 1 illustrates a bar graph displaying the upward trajectory of the AI market in recent years, sourced from Precedence Research.

The Indian government has invested heavily in developing the country’s digital infrastructure. In 2020, The Government of India increased its spending on Digital India to $477 million to boost AI, IoT, big data, cyber security, machine learning, and robotics. The artificial intelligence market is expected to witness significant growth in the BFSI(banking, financial services, and insurance) sectors on account of data mining applications, as there is an increase in the adoption of artificial intelligence solutions in data analytics, fraud detection, cybersecurity, and database systems.

Figure 2 illustrates a pie chart displaying the distribution of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) market share across various regions in 2022, sourced from Precedence Research.

Types of AI Systems and Impact on Employment

AI systems can be divided primarily into three types:

Narrow AI: This is a specific form of artificial intelligence that executes dedicated tasks with intelligence. It represents the prevailing and widely accessible type of AI in today’s technological landscape.

General AI: This represents an intelligence capable of efficiently undertaking any intellectual task akin to human capabilities. Aspiration driving the development of General AI revolves around creating a system with human-like cognitive abilities that enables autonomous, adaptable thinking. However, as of now, the realisation of a General AI system that comprehensively emulates human cognition remains elusive.

Super AI: It is a level of intelligence within systems where machines transcend human cognitive capacities, exhibit superior performance across tasks, and possess advanced cognitive properties. This extends from the culmination of the General AI.

Artificial intelligence has been incorporated into various aspects of our lives, ranging from virtual assistants on our mobile devices to advancements in customisation, cyber protection, and more. The growth of these systems is swift, and it is only a matter of time before the emergence of general artificial intelligence becomes a reality.

According to a report by PwC, the global GDP is estimated to be 14% higher in 2030 due to the accelerating development and utilisation of AI, which translates to an additional $15.7 trillion. This growth can be attributed to:

- Improvements in productivity resulting from the automation of business processes (including the use of robots and autonomous vehicles).

- Productivity gains from businesses integrating AI technologies into their workforce (assisted and augmented intelligence).

- Increased consumer demand for AI-enhanced products and services, resulting in personalised and/or higher-quality offerings.

The report suggests that the most significant economic benefits from AI will likely come from increased productivity in the near future. This includes automating mundane tasks, enhancing employees’ capabilities, and allowing them to focus on more stimulating and value-added work. Capital-intensive sectors such as manufacturing and transport are likely to experience the most significant productivity gains from AI, given that many operational processes in these industries are highly susceptible to automation. (2)

AI will disrupt many sectors and lead to the creation of many more. A compelling aspect to observe is how the Indian Job Market responds to AI and its looming threat to job security in the future.

The Indian Job Market

As of 2021, around 487.9 million people were part of the workforce in India out of 950.2 million people aged 15-64, the second largest after China. While there were 986.5 million people in China aged 15-64, there were 747.9 million people were part of the workforce.

India’s labour force participation rate (LFPR) at 51.3 per cent was less than China’s 76 per cent and way below the global average of 65 per cent.[3]

The low LFPR can be primarily attributed to two reasons:

Lack of Jobs

To reach its growth potential, India is expected to generate approximately 9 million nonfarm jobs annually until 2030, as per a report by McKinsey & Company. However, analysts suggest that the current rate of job creation falls significantly below this target, with only about 2.9 million nonfarm jobs being added each year from 2013 to 2019. [4]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, urban unemployment in India surged dramatically, peaking at 20.9% in the April-June 2020 quarter, coinciding with wage decline. Although the unemployment rate has decreased since then, full-time employment opportunities are scarce. Economists highlight a concerning trend where an increasing number of job-seekers, particularly the younger demographic, are turning towards low-paying casual jobs or opting for less stable self-employment options.[5]

This shift in employment pattern occurs alongside a broader outlook for the Indian economy, which is projected to achieve an impressive growth rate of 6.5% by the fiscal year ending in March 2025. Despite this optimistic growth forecast, the employment landscape appears to be evolving, leading individuals towards less secure and lower-paying work options. This shift raises pertinent concerns about the job market’s quality, stability, and inclusivity, particularly in accommodating the aspirations and needs of India’s burgeoning young workforce.

Low female labour participation

In 2021, China boasted an estimated female population of 478.3 million within the 15-64 age bracket, with an active female labour force of approximately 338.6 million. In stark contrast, despite India having a similar demographic size of 458.2 million women in that age group, its female labour force was significantly smaller, numbering only 112.8 million.[6]

This discrepancy underscores a notable disparity in India’s female labour force participation rate compared to China, despite both countries having sizeable female populations within the working-age bracket.[7]

Along with unemployment, there was also a crisis of under-employment and the collapse of small businesses, which has worsened since the pandemic.

AI vs the Indian Job Market

The presence and implications of AI cast a significant shadow on a country as vast and diverse as India. Amidst the dynamic and often unpredictable labour market, where employment prospects have been uncertain, addressing the impact of AI poses a considerable challenge for employers. Balancing the challenges and opportunities presented by AI while prioritising job security for the workforce is a critical obstacle to overcome.

The diverse facets of artificial intelligence (AI) and its capacity to transform industries across the board amplify the intricacy of the employment landscape in India. Employers confront the formidable challenge of devising effective strategies to incorporate AI technologies without compromising the livelihoods of their employees.

As per the findings of the Randstad Work Monitor Survey, a staggering 71% of individuals in India exhibit an inclination towards altering their professional circumstances within the next six months, either by transitioning to a new position within the same organisation or by seeking employment outside it. Furthermore, 23% of the workforce can be classified as passive job seekers, who are neither actively seeking new opportunities nor applying for them but remain open to considering job prospects if a suitable offer arises.

It also stated that at least half of Indian employees fear losing their jobs to AI, whereas the figure is one in three in developed countries. The growing concern among Indian workers stems from the substantial workforce employed in Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) and Knowledge Process Outsourcing (KPO), which are notably vulnerable to AI automation. Adding to this concern is India’s rapid uptake of AI technology, further accentuating the apprehension among employees.[8]

India’s role as a global hub for outsourcing and its proficiency in delivering diverse services have amplified the impact of AI adoption. The country has witnessed a swift embrace of AI technologies across various industries, magnifying workers’ concerns regarding the potential ramifications of their job security.

Goldman Sachs’ report highlights the burgeoning emergence of generative artificial intelligence (AI) and its potential implications for labour dynamics. The rapid evolution of this technology prompts questions regarding a possible surge in task automation, leading to cost savings in labour and amplified productivity. [9]

The labour market could confront significant disruptions if generative AI delivers its pledged capabilities. Analysing occupational tasks across the US and Europe revealed that approximately two-thirds of the current jobs are susceptible to AI automation. Furthermore, the potential of generative AI to substitute up to one-fourth of existing work further underscores its transformative potential.

Expanding these estimates on a global scale suggests that generative AI might expose the equivalent of 300 million full-time jobs to automation, signifying the far-reaching impact this technology could have on global labour markets.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning have exerted substantial influence across various professions and industries, particularly impacting job landscapes in sectors such as Indian IT, ITeS, BPO, and BPM. These sectors collectively employ over five million people and are India’s primary source of white-collar jobs. [10]

In a recent conversation with Business Today, Vardhman Jain, the founder and Vice Chairman of Access Healthcare, a Chennai-based BPO, highlighted the forthcoming impact of AI integration on the workplace. Jain indicated that AI implementation may cause customer service to be the sector most vulnerable to initial disruptions.

Jain pointed out that a substantial portion of services provided by the Indian BPO industry is focused on customer support, including voice and chat functions, data entry, and back-office services. He expounded upon how AI technologies, such as Natural Language Processing, Machine Learning, and Robotic Process Automation, possess the potential to significantly disrupt and automate these tasks within the industry.

While the discourse surrounding AI often centres on the potential for job displacement, several industry leaders argue that AI will not supplant human labour, but rather augment worker output and productivity.

At the 67th Foundation Day celebration of the All-India Management Association (AIMA), NR Narayan Murthy, as reported by Business Today, conveyed a noteworthy message by asserting that AI is improbable to supplant human beings, as humans will not allow it to happen.

Quoting Murthy’s statement from the report, “I think there is a mistaken belief that artificial intelligence will replace human beings; human beings will not allow artificial intelligence to replace them.” The Infosys founder stressed that AI has functioned as an assistive force rather than an outright replacement, enhancing human lives and making them more comfortable.[11]

McKinsey Global Institute’s study, “Generative AI and the Future of Work in America,” highlighted AI’s capability to expedite economic automation significantly. The report emphasised that while generative AI wouldn’t immediately eliminate numerous jobs, it would enhance the working methods of STEM, creative, business, and legal professionals.[12]

However, the report also underscored that the most pronounced impact of automation would likely affect job sectors such as office support, customer service, and food service employment.

While the looming threats posed by AI are undeniable, its evolution is expected to usher in a wave of innovation, leading to the birth of new industries and many job opportunities. This surge in new industries promises employment prospects and contributes significantly to economic growth by leveraging AI capabilities.

Changing employment Landscape

Having explored different perspectives and conversations on AI, it has become increasingly evident that the employment landscape is poised for significant transformation in the years ahead. This prompts a crucial enquiry: Will there remain a necessity for human jobs, and are our existing systems equipped to ensure equitable distribution of the benefits fostered by this technology developments?

- Universal Basic Income

Universal basic income (UBI) is a social welfare proposal in which all citizens of a given population regularly receive minimum income in the form of an unconditional transfer payment, that is, without a means test or need to work, in which case it would be called guaranteed minimum income.

Supporters of Universal Basic Income (UBI) now perceive it not only as a solution to poverty, but also as a potential answer to several significant challenges confronting contemporary workers: wage disparities, uncertainties in job stability, and the looming spectre of job losses due to advancements in AI.

Karl Widerquist, a professor of philosophy at Georgetown University-Qatar and an economist and political theorist, posits that the influence of AI on employment does not necessarily result in permanent unemployment. Instead, he suggests a scenario in which displaced workers shift into lower-income occupations, leading to increased competition and saturation in these sectors.

According to Widerquist, the initial effects of AI advancements might force white-collar workers into the gig economy or other precarious and low-paying employment. This shift, he fears, could trigger a downward spiral in wages and job security, exacerbating economic inequality.

He advocates for a Universal Basic Income (UBI) policy as a response to the challenges posed by AI and automation. Widerquist argues that such a policy would address employers’ failure to equitably distribute the benefits of economic growth, fuelled in part by automation, among workers. He sees UBI as a potential solution to counter the widening disparity in wealth distribution resulting from these technological advancements.[13]

A study conducted by researchers at Utrecht University, Netherlands, from 2017 to 2019 led to the implementation of basic income for unemployed individuals who previously received social assistance. The findings showcase an uptick in labour market engagement. This increase wasn’t solely attributed to the financial support offered by Universal Basic Income (UBI) but also to removing conditions—alongside sanctions for non-compliance—typically imposed on job seekers.[14]

Specifically, participants exempted from the obligation to actively seek or accept employment demonstrated a higher likelihood of securing permanent contracts, as opposed to the precarious work arrangements highlighted by Widerquist.

While UBI experiments generally do not demonstrate a significant trend of workers completely exiting the labour market, instances of higher payments have resulted in some individuals reducing their working hours. This nuanced impact showcases the varying effects of UBI on labour participation, highlighting both increased job security for some and a choice for others to adjust their work hours due to enhanced financial stability.

In exploring the potential for Universal Basic Income (UBI), it becomes evident that while the concept holds promise, its implementation and efficacy are subject to multifaceted considerations. The diverse socioeconomic landscape, coupled with the scale and complexity of India’s population, presents both opportunities and challenges for UBI.

UBI’s potential to alleviate poverty, enhance social welfare, and address economic disparities in a country as vast and diverse as India is compelling. However, the feasibility of funding such a program, ensuring its equitable distribution, and navigating its impact on existing welfare schemes requires careful deliberation.

Possible Tax Solutions

- Robot Tax

The essence of a robot tax lies in the notion that companies integrating robots into their operations should bear a tax burden given that these machines replace human labour.

There exist various arguments advocating for a robot tax. Initially, it aimed to safeguard human employment by dissuading firms from substituting humans with robots. Additionally, while companies may prefer automation, imposing a robot tax can generate government revenue to offset the decline in funds from payroll and income taxes. Another crucial argument favouring this tax is rooted in allocation efficiency: robots neither contribute to payroll nor income taxes. Taxing robots at a rate similar to human labour aligns with economic efficiency to prevent distortions in resource allocation.

In various developed economies, such as the United States, the prevailing taxation system presents a bias toward artificial intelligence (AI) and automation over human workforce. This inclination, fueled by tax incentives, may lead to investments in automation solely for tax benefits rather than for the actual potential increase in profitability. Furthermore, the failure to tax robots can exacerbate income inequality as the share of labor in national income diminishes.

One possible solution to address this issue is the implementation of a robot tax, which could generate revenue that could be redistributed as Universal Basic Income (UBI) or as support for workers who have lost their jobs due to the adoption of robotic systems and AI and are unable to find new employment opportunities.

- Digital Tax

The discourse surrounding digital taxation primarily centers on two key aspects. Firstly, it grapples with the challenge of maintaining tax equity between traditional and digital enterprises. Digital businesses have benefited from favorable tax structures, such as advantageous tax treatment for income derived from intellectual property, accelerated amortization of intangible assets, and tax incentives for research and development. However, there is a growing concern that these preferences may result in unintended tax advantages for digital businesses, potentially distorting investment trajectories instead of promoting innovation.

Secondly, the issue arises from digital companies operating in countries with no physical presence yet serving customers through remote sales and service platforms. This situation presents a dilemma regarding traditional corporate income tax regulations. Historically, digital businesses paid corporate taxes solely in countries where they maintained permanent establishments, such as headquarters, factories, or storefronts. Consequently, countries where sales occur or online users reside have no jurisdiction over a firm’s income, leading to taxation challenges.

Several approaches have been suggested to address the taxation of digital profits. One approach involves expanding existing frameworks, for instance, a country may extend its Value-Added Tax (VAT) or Goods and Services Tax (GST) to encompass digital services or broaden the tax base to include revenues generated from digital goods and services. Alternatively, there is a need to implement a separate Digital Service Tax (DST).

While pinpointing the ultimate solution remains elusive, ongoing experimentation and iterative processes are expected to guide us toward a resolution that aligns with the need for a larger consensus. With each experiment and accumulated knowledge, we move closer to uncovering an approach that best serves the collective requirements.[15]

Reimagining the Future

The rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) stands as a transformative force reshaping the industry and business landscape. As AI continues to revolutionise how we work and interact, staying ahead in this rapidly evolving landscape is not just an option, but a necessity. Embracing AI is not merely about adapting to change; it is also about proactive readiness and strategic positioning. Whether you’re a seasoned entrepreneur or a burgeoning startup, preparing for the AI revolution involves a multifaceted approach encompassing automation, meticulous research, strategic investment, and a keen understanding of how AI can augment and revolutionise your business. PwC’s report lists some crucial steps to prepare one’s business for the future and stay ahead. [16]

Understand AI’s Impact: Start by evaluating the industry’s technological advancements and competitive pressure. Identify operational challenges AI can address, disruptive opportunities available now and those on the horizon.

Prioritise Your Approach: Determine how AI aligns with business goals. Assess your readiness for change— are you an early adopter or follower? Consider feasibility, data availability, and barriers to innovation—Prioritise automation and decision augmentation processes based on potential savings and data utilisation.

Talent, Culture, and Technology: While AI investments might seem high, costs are expected to decrease over time. Embrace a data-driven culture and invest in talent like data scientists and tech specialists. Prepare for a hybrid workforce, combining AI’s capabilities with human skills like creativity and emotional intelligence.

Establish Governance and Trust: Trust and transparency are paramount. Consider the societal and ethical implications of AI. Build stakeholder trust by ensuring AI transparency and unbiased decision-making. Manage data sources rigorously to prevent biases and integrate AI management with overall technology transformation.

Getting ready for Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not just about new technology; it is an intelligent strategy. Understanding how AI fits one’s goals is crucial; prioritising where it can help, building the right skills, and setting clear rules are essential. As AI becomes more common, it is not about robots taking over, but humans and AI working together. By planning and embracing AI wisely, businesses can stay ahead and create innovative solutions in the future.

References:

[1] Precedence Research. “Artificial Intelligence (AI) Market.” October 2023. Accessed November 14, 2023. https://www.precedenceresearch.com/artificial-intelligence-market

[2] Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC). “Sizing the prize, PwC’s Global Artificial Intelligence Study.” October 2017. Accessed November 14, 2023. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/data-and-analytics/publications/artificial-intelligence-study.html#:~:text=The%20greatest%20economic%20gains%20from,of%20the%20global%20economic%20impact.

[3] World Bank. “Labor force, total – India 2021.” Accessed November 12, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.IN?locations=IN

[4] McKinsey & Company. “India’s Turning Point.” August 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Featured%20Insights/India/Indias%20turning%20point%20An%20economic%20agenda%20to%20spur%20growth%20and%20jobs/MGI-Indias-turning-point-Executive-summary-August-2020-vFinal.pdf

[5] Dugal, Ira. “Where are the jobs? India’s world-beating growth falls short.” Reuters, May 31, 2023. Accessed November 14, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/india/despite-world-beating-growth-indias-lack-jobs-threatens-its-young-2023-05-30/

[6] Government of India. Ministry of Labour and Employment. “Labour and Employment Statistics 2022.” July 2022. https://dge.gov.in/dge/sites/default/files/2022-08/Labour_and_Employment_Statistics_2022_2com.pdf

[7] Deshpande, Ashwini, and Akshi Chawla. “It Will Take Another 27 Years for India to Have a Bigger Labour Force Than China’s.” The Wire, July 27, 2023. https://thewire.in/labour/india-china-population-labour-force

[8] Randstad. “Workmonitor Pulse Survey.” Q3 2023. https://www.randstad.com/workforce-insights/future-work/ai-threatening-jobs-most-workers-say-technology-an-accelerant-for-career-growth/

[9] Briggs, Joseph, and Devesh Kodnani. “The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth.” Goldman Sachs, March 26, 2023. https://www.key4biz.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Global-Economics-Analyst_-The-Potentially-Large-Effects-of-Artificial-Intelligence-on-Economic-Growth-Briggs_Kodnani.pdf

[10] Chaturvedi, Aakanksha. “‘Might take toll on low-skilled staff’: How AI can cost BPO, IT employees their jobs.” Business Today, April 5, 2023. https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/corporate/story/might-take-toll-on-low-skilled-staff-how-ai-can-cost-bpo-it-employees-their-jobs-376172-2023-04-05

[11] Sharma, Divyanshi. “Can AI take over human jobs? This is what Infosys founder NR Narayan Murthy thinks.” India Today, February 27, 2023. https://www.indiatoday.in/technology/news/story/can-ai-take-over-human-jobs-this-is-what-infosys-founder-nr-narayan-murthy-thinks-2340299-2023-02-27

[12] McKinsey Global Institute. “Generative AI and the future of work in America.” July 26, 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/generative-ai-and-the-future-of-work-in-america

[13] Kelly, Philippa. “AI is coming for our jobs! Could universal basic income be the solution?” The Guardian, November 16, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/nov/16/ai-is-coming-for-our-jobs-could-universal-basic-income-be-the-solution

[14] Utrecht University. “What works (Weten wat werkt).” March 2020. https://www.uu.nl/en/publication/final-report-what-works-weten-wat-werkt

[15] Merola, Rossana. “Inclusive Growth in the Era of Automation and AI: How Can Taxation Help?” *Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence* 5 (2022). Accessed November 23, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frai.2022.867832

[16] Rao, Anand. “A Strategist’s Guide to Artificial Intelligence.” PwC, May 10, 2017.https://www.strategy-business.com/article/A-Strategists-Guide-to-Artificial-Intelligence