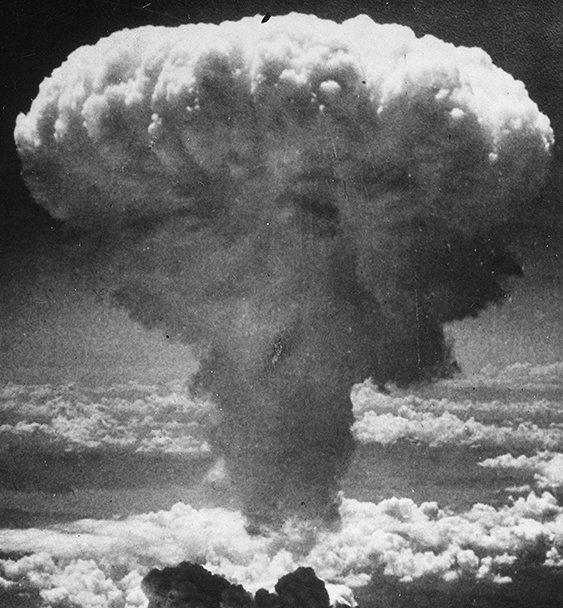

As we commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings, the world is drifting as close to another nuclear confrontation as it has been in decades.

With Israeli and American attacks on Iranian nuclear energy sites, India and Pakistan going to war in May, and escalating violence between Russia and NATO-backed forces in Ukraine, the shadow of another nuclear war looms large over daily life.

EIGHTY YEARS OF LIES

The dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan was a power play, intended to strike fear into the hearts of world leaders, especially in the Soviet Union and China.

The United States remains the only nation to have dropped an atomic bomb in anger. While the dates of August 6 and August 9, 1945, are seared into the popular conscience of all Japanese people, those days hold far less salience in American society.

When discussed at all in the U.S., this dark chapter in human history is usually presented as a necessary evil, or even a day of liberation—an event that saved hundreds of thousands of lives, prevented the need for an invasion of Japan, and ended the Second World War early. This, however, could not be further from the truth.

American generals and war planners agreed that Japan was on the point of collapse, and had, for weeks, been attempting to negotiate a surrender. The decision, then, to incinerate hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians was one taken to project American power across the world, and to stymie the rise of the Soviet Union.

“It always appeared to us that, atomic bomb or no atomic bomb, the Japanese were already on the verge of collapse,” General Henry Arnold, Commanding General of the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1945, wrote in his 1949 memoirs.

“It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages” – Gen Hap Arnold

Arnold was far from alone in this assessment. Indeed, Fleet Admiral William Leahy, the Navy’s highest-ranking officer during World War II, bitterly condemned the United States for its decision and compared his own country to the most savage regimes in world history.

As he wrote in 1950:

“It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages.”

By 1945, Japan had been militarily and economically exhausted. Losing key allies Italy in 1943 and Germany by May 1945, and facing the immediate prospect of an all-out Soviet invasion of Japan, the country’s leaders were frantically pursuing peace negotiations. Their only real condition appeared to be that they wished to keep as a figurehead the emperor—a position that, by some accounts, dates back more than 2,600 years.

“I am convinced,” former President Herbert Hoover wrote to his successor, Harry S. Truman, “if you, as President, will make a shortwave broadcast to the people of Japan—tell them they can have their emperor if they surrender, that it will not mean unconditional surrender except for the militarists—you’ll get a peace in Japan—you’ll have both wars over.”

Many of Truman’s closest advisors told him the same thing. “I am absolutely convinced that had we said they could keep the emperor, together with the threat of an atomic bomb, they would have accepted, and we would never have had to drop the bomb,” said John McCloy, Truman’s Assistant Secretary of War.

“The war might have ended weeks earlier,” he said, “If the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the emperor.” – Gen Douglas MacArthur

Nevertheless, Truman initially took an absolutist position, refusing to hear any Japanese negotiating caveats. This stance, according to General Douglas MacArthur, Commander of Allied Forces in the Pacific, actually lengthened the war. “The war might have ended weeks earlier,” he said, “If the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the emperor.” Truman, however, dropped two bombs, then reversed his position on the emperor, in order to stop Japanese society from falling apart.

At that point in the war, however, the United States was emerging as the sole global superpower and enjoyed an unprecedented position of influence. The dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan underscored this; it was a power play, intended to strike fear into the hearts of world leaders, especially in the Soviet Union and China.

FIRST JAPAN, THEN THE WORLD

“Japan was already defeated, and dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary…[it was] no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at this very moment, seeking a way to surrender with a minimum loss of face.” – President Ike Eisenhower

Hiroshima and Nagasaki drastically curbed the U.S.S.R.’s ambitions in Japan. Joseph Stalin’s forces had invaded and permanently annexed Sakhalin Island in 1945 and planned to occupy Hokkaido, Japan’s second-largest island. The move likely prevented the island nation from coming under the Soviet sphere of influence.

To this day, Japan remains deeply tied to the U.S., economically, politically, and militarily. There are around 60,000 U.S. troops in Japan, spread across 120 military bases.

Many in Truman’s administration wished to use the atom bomb against the Soviet Union as well. President Truman, however, worried that the destruction of Moscow would lead the Red Army to invade and destroy Western Europe as a response. As such, he decided to wait until the U.S. had enough warheads to completely destroy the U.S.S.R. and its military in one fell swoop.

War planners estimated this figure to be around 400. To that end, Truman ordered the immediate ramping up of production. Such a strike, we now know, would have caused a nuclear winter that would have permanently ended all organised life on Earth.

The decision to destroy Russia was met with stiff opposition among the American scientific community. It is now widely believed that Manhattan Project scientists, including Robert J. Oppenheimer himself, passed nuclear secrets to Moscow in an effort to speed up their nuclear project and develop a deterrent to halt this doomsday scenario. This part of history, however, was left out of the 2023 biopic movie.

By 1949, the U.S.S.R. was able to produce a credible nuclear deterrent before the U.S. had produced sufficient quantities for an all-out attack, thus ending the threat and bringing the world into the era of mutually assured destruction.

“Certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated,” concluded a 1946 report from the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe and future president, was of the same opinion, stating that:

“Japan was already defeated, and dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary…[it was] no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at this very moment, seeking a way to surrender with a minimum loss of face.”

Nevertheless, both Truman and Eisenhower publicly toyed with the idea of using nuclear weapons against China to stop the rise of Communism and to defend their client regime in Taiwan. It was only the development of a Chinese warhead in 1964 that led to the end of the danger, and, ultimately, the détente era of good relations between the two powers that lasted until President Obama’s Pivot to Asia.

Ultimately, then, the people of Japan were the collateral damage in a giant U.S. attempt to project its power worldwide. As Brigadier General Carer Clarke, head of U.S. intelligence on Japan wrote, “When we didn’t need to do it, and we knew we didn’t need to do it, and they knew that we knew we didn’t need to do it, we used them [Japanese citizens] as an experiment for two atomic bombs.”

TIPTOEING CLOSER TO ARMAGEDDON

The danger of nuclear weapons is far from over. Today, Israel and the United States – two nations with atomic weaponry – attack Iranian nuclear facilities. Yet their continued, hyper-aggressive actions against their foes only suggest to other countries that, unless they too possess weapons of mass destruction, they will not be safe from attack. North Korea, a country with a conventional and nuclear deterrent, faces no such air strikes from the U.S. or its allies. These actions, therefore, will likely result in more nations pursuing nuclear ambitions.

Earlier this year, India and Pakistan (two more nuclear-armed states) came into open conflict thanks to disputes over terrorism and Jammu and Kashmir. Many influential individuals on both sides of the border were demanding their respective sides launch their nukes – a decision that could also spell the end of organised human life. Thankfully, cooler heads prevailed.

Meanwhile, the war in Ukraine continues, with NATO forces urging President Zelensky to up the ante. Earlier this month, President Trump himself reportedly encouraged the Ukrainian leader to use his Western-made weapons to strike Moscow.

It is precisely actions such as these that led the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists to move its famous Doomsday Clock to 89 seconds to midnight, the closest the world has ever been to catastrophe.

“The war in Ukraine, now in its third year, looms over the world; the conflict could become nuclear at any moment because of a rash decision or through accident or miscalculation,” they wrote in their explanation, adding that conflicts in Asia could spiral out of control into a wider war at any point, and that nuclear powers are updating and expanding their arsenals.

The Pentagon, too, is recruiting Elon Musk to help it build what it calls an American Iron Dome. While this move is couched in defensive language, such a system – if successful – would grant the U.S. the ability to launch nuclear attacks anywhere in the world without having to worry about the consequences of a similar response.

Thus, as we look back at the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 80 years ago, we must understand that not only were they entirely avoidable, but that we are now closer to a catastrophic nuclear confrontation than many people realise.

![]() This article was published earlier in MintPress News and is republished under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.

This article was published earlier in MintPress News and is republished under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.

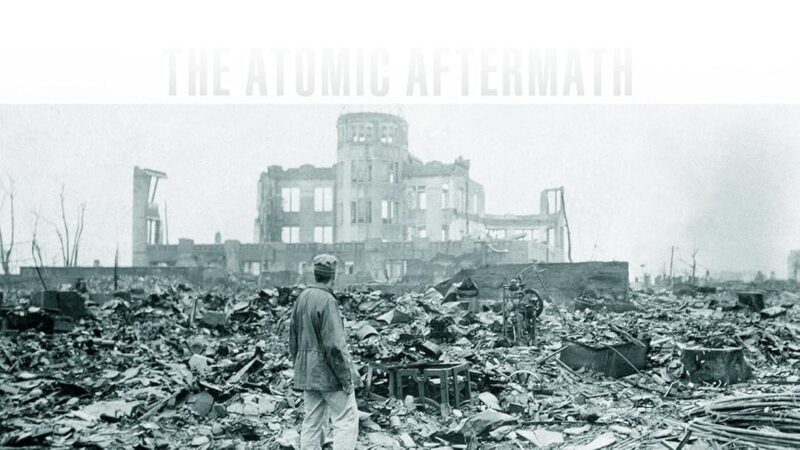

Feature Image: Hiroshima, several months after the atomic bombing. Air Force photo from national archives nsarchive.gwu.edu

Mission map for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945. Scale is not consistent due to the curvature of the Earth. Angles and locations are approximate. Kokura was included as the original target for Aug. 9 but weather obscured visibility; Nagasaki was chosen instead. (Mr.98, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Mission map for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945. Scale is not consistent due to the curvature of the Earth. Angles and locations are approximate. Kokura was included as the original target for Aug. 9 but weather obscured visibility; Nagasaki was chosen instead. (Mr.98, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

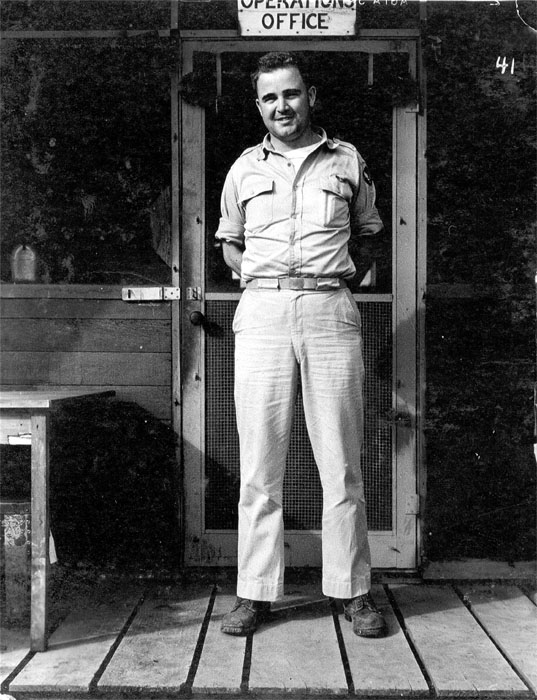

Brigadier General Charles W. Sweeney, pilot of the aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. (Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)

Brigadier General Charles W. Sweeney, pilot of the aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. (Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)