We start the year 2023 with an examination of philosophy and society and through it the social evil of caste. The origin of the caste system in Hindu society lies buried in many myths and misconceptions. Caste is often linked by many to the core of Hindu philosophy. This is a deeply flawed understanding. The caste system has been and continues to be a tool of power and economic exploitation by oppressing large segments of the population. It is largely an invention by the clergy to establish their power and domination through rituals and codes and by ascribing to them a forced religious sanctity. As it also becomes convenient to the rulers, caste and class are prevalent in all societies. Philosophy and true religion, as Andreas points out in this working paper, have had nothing to do with caste or class. – TPF Editorial Team

Introduction

Intercultural philosophy is absolutely necessary in order to cope with the current and new phase of hybrid globalization, which is dissolving all kinds of traditional identities. Whereas the current reaction to this process is the development of ideologies centred on the idea of “we against the rest”, whoever the “Rest” might be, we need to construct positive concepts of identity, which does not exclude but include the other. These can be based on the mutual recognition of the civilizations of the world and their philosophies. According to Karl Jaspers the godfather of intercultural philosophy, between the sixth and third century BC the development of great cities, and the development in agriculture and sciences led to a growth of the populace that forced humankind to develop new concepts of thinking. He labelled this epoch as the axial age of world history in which everything turned around. He even argued that in this time the particular human being or human thinking was born with which we still live today – my thesis is that all human religions, civilizations and philosophies share the same problems and questions but did find different solutions.

A vivid example might be the relationship between happiness and suffering. In the philosophy of the Greek philosopher Aristotle, to achieve eudemonia or happiness in your earthly life was the greatest aim whereas in a popular understanding of Karma, life is characterized by suffering and the aim is to overcome suffering by transcending to Nirvana. You see, the problem is the same, but there are different solutions in various philosophies. Although Jaspers didn’t share the reduction of philosophy and civilization to the European or even German experience and included mainly the Chinese and Indian civilization, he nevertheless excluded the African continent and both Americas, Muslim civilization as well as the much older Egyptian civilization. So, although he enlarged our knowledge and understanding of civilizations his point of reference was still “Western modernity” and within it, the concept of functional differentiation played the major role.

Another solution is embodied in the belief of the three monotheistic religions, that an omnipotent god is the unifying principle despite all human differentiations and even the differences between the living and the dead, love and hate, between war and peace, men and women, old and young, linear and non-linear understanding of time, beginning and ending, happiness and suffering. In this belief system, we are inevitably confronted with unsurpassable contrasts, conflicts and contradictions – but an all-powerful and absolute good god is the one who is uniting all these contrasts.

In principle in Chinese philosophy, we have the same problem – but instead of an all-powerful God, we as humans have the task to live in harmony with the cosmic harmony. So, I really think that we humans share the same philosophical problems – how to explain and overcome death, evil, suffering, and the separation from transcendence. Although Karl Jaspers could be seen as the founding father of intercultural philosophy, I think he put too much emphasis solely on the functional differentiation that an ever-growing populace could live together without violence. In my view, the questions of life and death are running deeper. I would not exclude functional differentiation as one of the driving forces of human development but at least we also need an understanding of human existence that is related to transgressing the contrasts of life.

In this draft, I would like to give some impressions concerning this same problem based on my limited knowledge of Indian philosophy and religion and try to show that both are opposing the caste system as well as any kind of dogmatism. An Indian student asked me in the run-up to this draft how one could understand Indian philosophy if one had not internalized the idea of rebirth since you are a baby. From her point of view, the whole thinking on the Indian subcontinent is thus determined by the idea of rebirth – this problem will still occupy us in the question of whether the terrible caste system in India is compatible with the original intentions of the Indian religions, whether it can be derived from them or contradicts them. I will try to give a reason for the assumption that Indian philosophy is quite universal and at the same time open to different strands of philosophical thought, retaining its core.

In its essence, it is about Karma, rebirth, and Moksha. An understanding of Atman and Brahman is essential. Atman is the soul, indestructible, and is part of Brahman (omnipresent God). When Atman continues to reform and refine itself through rebirths aspiring to become one with Brahman, that is Moksha. To attain Moksha is the purpose of each life. Moksha is being one with God…a state where there is no more rebirths. Of course, differences are there in interpreting Atman and Brahman, depending on the Advaita and Dwaita schools of philosophy. Ultimately both narrow down to the same point – Moksha. Karma is the real part. True Karma is about doing your work in life as duty and dispassionately. Understanding that every life form has a purpose, one should go about it dispassionately. Easier said than done. Understanding this is the crux. In an ideal life where one has a full understanding of Karma and performs accordingly, he/she will have no rebirth. Indian philosophy is careful to separate the religious and social practices of the common folks and the high religion. Hence Caste and hierarchy are not part of the philosophical discourse, although many make the mistake of linking them. Caste, like in any other religion, is a clergy-driven issue for power and economic exploitation.

Indian Philosophy (or, in Sanskrit, Darshanas), refers to any of several traditions of philosophical thought that originated in the Indian subcontinent, including Hindu philosophy, Buddhist philosophy, and Jain philosophy. It is considered by Indian thinkers to be a practical discipline, and its goal should always be to improve human life. In contrast to the major monotheistic religions, Hinduism does not draw a sharp distinction between God and creation (while there are pantheistic and panentheistic views in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, these are minority positions). Many Hindus believe in a personal God and identify this God as immanent in creation. This view has ramifications for the science and religion debate, in that there is no sharp ontological distinction between creator and creature. Philosophical theology in Hinduism (and other Indic religions) is usually referred to as dharma, and religious traditions originating on the Indian subcontinent, including Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism, are referred to as dharmic religions. Philosophical schools within dharma are referred to as darśana.

Religion and science

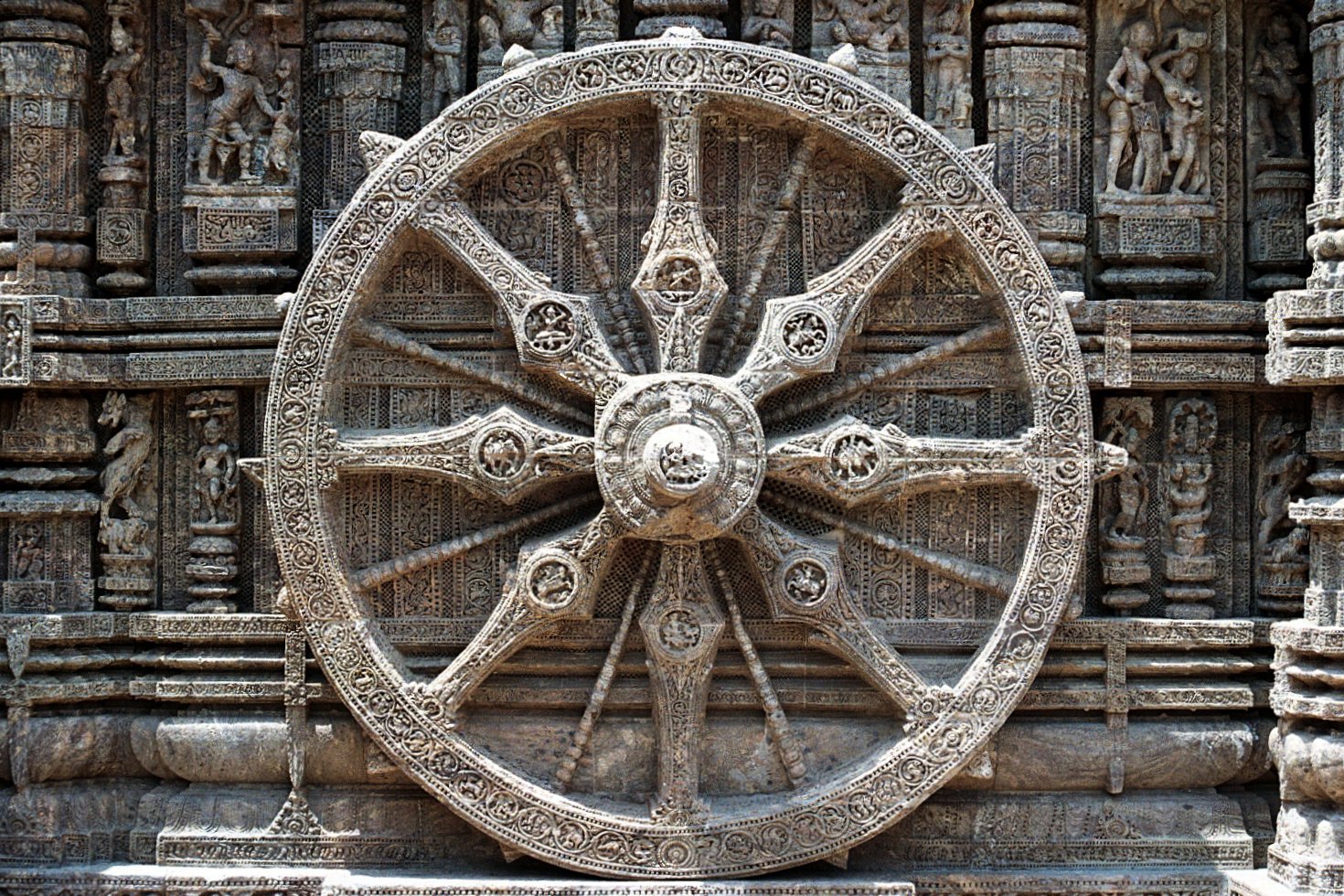

One factor that unites dharmic religions is the importance of foundational texts, which were formulated during the Vedic period, between ca. 1600 and 700 BCE. These include the Véda (Vedas), which contain hymns and prescriptions for performing rituals, Brāhmaṇa, accompanying liturgical texts, and Upaniṣad, metaphysical treatises. The Véda appeals to a wide range of gods who personify and embody natural phenomena such as fire (Agni) and wind (Vāyu). More gods were added in the following centuries (e.g., Gaṇeśa and Sati-Parvati in the fourth century CE). Ancient Vedic rituals encouraged knowledge of diverse sciences, including astronomy, linguistics, and mathematics. Astronomical knowledge was required to determine the timing of rituals and the construction of sacrificial altars. Linguistics developed out of a need to formalize grammatical rules for classical Sanskrit, which was used in rituals. Large public offerings also required the construction of elaborate altars, which posed geometrical problems and thus led to advances in geometry.

Classic Vedic texts also frequently used very large numbers, for instance, to denote the age of humanity and the Earth, which required a system to represent numbers parsimoniously, giving rise to a 10-base positional system and a symbolic representation for zero as a placeholder, which would later be imported in other mathematical traditions. In this way, ancient Indian dharma encouraged the emergence of the sciences.

The relationship between science and religion on the Indian subcontinent is complex, in part because the dharmic religions and philosophical schools are so diverse.

Around the sixth–fifth century BCE, the northern part of the Indian subcontinent experienced extensive urbanization. In this context, medicine became standardized (āyurveda). This period also gave rise to a wide range of philosophical schools, including Buddhism, Jainism, and Cārvāka. The latter defended a form of metaphysical naturalism, denying the existence of gods or karma. The relationship between science and religion on the Indian subcontinent is complex, in part because the dharmic religions and philosophical schools are so diverse. For example, Cārvāka proponents had a strong suspicion of inferential beliefs, and rejected Vedic revelation and supernaturalism in general, instead favouring direct observation as a source of knowledge. Such views were close to philosophical naturalism in modern science, but this school disappeared in the twelfth century. Nevertheless, already in classical Indian religions, there was a close relationship between religion and the sciences.

Opposing dogmatism: the role of colonial rule

The word “Hinduism” emerged in the nineteenth century, and some scholars have argued that the religion did so, too. They say that British colonials, taken aback by what they experienced as the pagan profusion of cults and gods, sought to compact a religious diversity into a single, subsuming entity. Being literate Christians, they looked for sacred texts that might underlay this imputed tradition, enlisting the assistance of the Sanskrit-reading Brahmins. A canon and an attendant ideology were extracted, and with it, Hinduism. Other scholars question this history, insisting that a self-conscious sense of Hindu identity preceded this era, defined in no small part by contrast to Islam. A similar story could be told about other world religions. We shouldn’t expect to resolve this dispute, which involves the weightings we give to points of similarity and points of difference. And scholars on both sides of this divide acknowledge the vast pluralism that characterized, and still characterizes, the beliefs, rituals, and forms of worship among the South Asians who have come to identify as Hindu.

Here I would like to mention some of the scriptures in Hinduism: The longest of these is the religious epic, the Mahabharata, which clocks in at some 180000 thousand words, which is ten times the size of the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer combined. Then there’s the Ramayana, which recounts the heroic attempts of Prince Rama to rescue his wife from a demon king. It has as many verses as the Hebrew bible. The Vedas which are the oldest Sanskrit scriptures include hymns and other magical and liturgical; and the Rig-Veda, the oldest, consists of nearly 11 000 lines of hymns of praise to the gods.

But the Rig Veda does not only contain hymns of praise of God but a philosophical exposition which can be compared with Hegel’s conceptualization of the beginning in his “Logic”, which is not just about logic in the narrow sense but about being and non-being:

In the Rig Veda we find the following hymn:

Nasadiya Sukta (10. 129)

There was neither non-existence nor existence then;

Neither the realm of space nor the sky which is beyond;

What stirred? Where? In whose protection?

There was neither death nor immortality then;

No distinguishing sign of night nor of day;

That One breathed, windless, by its own impulse;

Other than that there was nothing beyond.

Darkness there was at first, by darkness hidden;

Without distinctive marks, this all was water;

That which, becoming, by the void was covered;

That One by force of heat came into being.

Who really knows? Who will here proclaim it?

Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation?

Gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe.

Who then knows whence it has arisen?

Whether God’s will created it, or whether He was mute;

Perhaps it formed itself, or perhaps it did not;

Only He who is its overseer in highest heaven knows,

Only He knows, or perhaps He does not know.

—Rigveda 10.129 (Abridged, Tr: Kramer / Christian)

Nasadiya Sukta begins rather interestingly, with the statement – “Then, there was neither existence nor non-existence.” It ponders over the when, why and by whom of creation in a very sincere contemplative tone and provides no definite answers. Rather, it concludes that the gods too may not know, as they came after creation. And maybe the supervisor of creation in the highest heaven knows, or maybe even he does not know.

The philosophical character of this hymn becomes obvious when stating that there was something or someone who created even the gods. This question might be similar to the one that created the big bang thirteen billion years ago. In my view, the Rigveda is the most elaborate Veda opposing any kind of dogmatism, any ideology. Instead, it gives reason for the assumption which is of paramount importance in an ever-changing world, that there is no absolute knowledge, there is an increasing sense of unsureness, and we can’t rely on fixed rules – but that we are responsible for our actions.

Müller made the term central to his criticism of Western theological and religious exceptionalism (relative to Eastern religions) focusing on a cultural dogma which held “monotheism” to be both fundamentally well-defined and inherently superior to differing conceptions of God.

The second problem is related to the question of whether this hymn should be interpreted as monotheistic, dualistic or polytheistic. Some scholars like Frederik Schelling have invented the term Henotheism (from, greek ἑνός θεοῦ (henos theou), meaning ‘of one god’) is the worship of a single god while not denying the existence or possible existence of other deities. Schelling coined the word, and Frederik Welcker (1784–1868) used it to depict primitive monotheism in ancient Greeks. Max Müller (1823–1900), a German philologist and orientalist, brought the term into wider usage in his scholarship on the Indian religions, particularly Hinduism whose scriptures mention and praise numerous deities as if they are one ultimate unitary divine essence. Müller made the term central to his criticism of Western theological and religious exceptionalism (relative to Eastern religions) focusing on a cultural dogma which held “monotheism” to be both fundamentally well-defined and inherently superior to differing conceptions of God.

Mueller in the end emphasizes that henotheism is not a primitive form of monotheism but a different conceptualization. We find a similar passage in the gospel of John in which it is stated:

1In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2 He was with God in the beginning. 3 Through him all things were made; without him, nothing was made that has been made. 4 In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind. 5 The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

It is clearly written that in the beginning there was the word – not God. In the original Greek version of this gospel, the term logos is used, and Hegel made this passage the foundation of his whole philosophy. Closely related to the Rig Veda is the concept of Atman. Ātman (Atma, आत्मा, आत्मन्) is a Sanskrit word which means “essence, breath, soul” and which is for the first time discussed in the Rig-Veda. Nevertheless, this concept is most cherished in the Upanishads, which are written precisely between the 8th to 5th centuries B.C., the period in which according to Jaspers the axial age began. Again, this concept is an attempt to reconcile the various differentiations which were necessary for the function of a society with an ever-increasing population.

I want to highlight that Hinduism – in its Vedic and classic variants – did not support the caste system; but that it rigorously opposed it in practice and principle. Even after the emergence of the caste system, Hindu society still saw considerable occupational and social mobility. Moreover, Hinduism created legends to impress on the popular mind the invalidity of the caste system – a fact further reinforced by the constant efflorescence of reform movements throughout history. The caste system survived despite this because of factors that ranged from the socio-economic to the ecological sphere, which helped sustain and preserve the balance among communities in a non-modern world.

It would be absolutely necessary to demolish the myth that the caste system is an intrinsic part of Hinduism as a religion as well as a philosophy. Although, there is a historically explainable link between both but not one which I would label a necessary or logical connection. Of course, the proponents of the caste system tried to legitimize the caste system by using references from the ancient scriptures – but as we maintain we must not understand Hinduism just in relation to Dharma if we would understand it just as jati or birth-based social division.

The myth of the caste system being an intrinsic part of Hinduism is a discourse in the meaning in which Foucault has used this concept as just exercising power.

I’m not sure whether this interpretation represents the major understanding in India, but I think it might be essential in a globalized world to debunk this only seemingly close relation, which has just a historical dimension and would therefore be a vivid example just of a discursive practice. The myth of the caste system being an intrinsic part of Hinduism is a discourse in the meaning in which Foucault has used this concept as just exercising power.

This discourse is believed by orthodox elements in Hinduism as well as propagated by elements outside of Hinduism who are trying to proselyte Hindus. I would like to treat this problem a little bit more extensively because it might be used for other religions and civilizations, too, in which suppression and dominance are seemingly legitimized by holy scriptures but by taking a closer look this relation is just a discourse of power.

Nevertheless, there is a very old text of Hinduism in which the caste system is legitimized. It is called Manusmṛiti (Sanskrit: मनुस्मृति), also spelt as Manusmruti, is an ancient legal text. It was one of the first Sanskrit texts to have been translated into English in 1794, by Sir William Jones, and was used to formulate the Hindu law by the British colonial government.

Over fifty manuscripts of the Manusmriti are now known, but the earliest discovered, most translated and presumed authentic version since the 18th century has been the “Calcutta manuscript with Kulluka Bhatta commentary”.

How did caste come about?

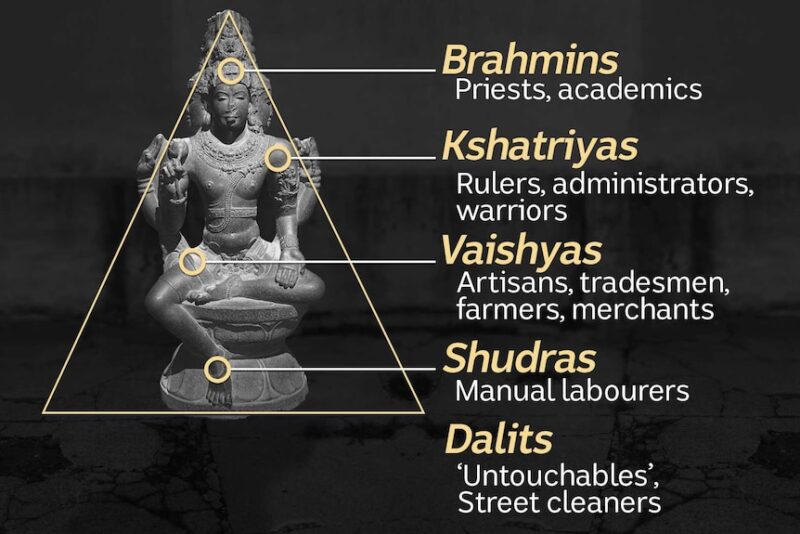

Manusmriti, widely regarded to be the most important and authoritative book on Hindu law and dating back to at least 1,000 years before Christ was born, seems to “acknowledge and justify the caste system as the basis of order and regularity of society”. The caste system divides Hindus into four main categories – Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and the Shudras. Many believe that the groups originated from Brahma, the Hindu God of creation.

At the top of the hierarchy were the Brahmins who were mainly teachers and intellectuals and are believed to have come from Brahma’s head. Then came the Kshatriyas, or the warriors and rulers, supposedly from his arms. The third slot went to the Vaishyas, or the traders, who were created from his thighs. At the bottom of the heap were the Shudras, who came from Brahma’s feet and did all the menial jobs. The main castes were further divided into about 3,000 castes and 25,000 sub-castes, each based on their specific occupation. Outside of this Hindu caste system were the achhoots – the Dalits or the untouchables.

How does caste work?

For centuries, caste has dictated almost every aspect of Hindu religious and social life, with each group occupying a specific place in this complex hierarchy. Rural communities have long been arranged on the basis of castes – the upper and lower castes almost always lived in segregated colonies, the water wells were not shared, Brahmins would not accept food or drink from the Shudras, and one could marry only within one’s caste. The system bestowed many privileges on the upper castes while sanctioning repression of the lower castes by privileged groups.

New research shows that hard boundaries between the social groups were only set by British colonial rulers who made caste India’s defining social feature when they used censuses to simplify the system, primarily to create a single society with a common law that could be easily governed.

Often criticized for being unjust and regressive, it remained virtually unchanged for centuries, trapping people into fixed social orders from which it was impossible to escape. Despite the obstacles, however, some Dalits and other low-caste Indians, such as BR Ambedkar who authored the Indian constitution, and KR Narayanan who became the nation’s first Dalit president, have risen to hold prestigious positions in the country. Historians, though, say that until the 18th Century, the formal distinctions of caste were of limited importance to Indians, social identities were much more flexible, and people could move easily from one caste to another. New research shows that hard boundaries between the social groups were only set by British colonial rulers who made caste India’s defining social feature when they used censuses to simplify the system, primarily to create a single society with a common law that could be easily governed.

So, the caste system in its strict interpretation is an invention of British rules – of course, it existed already in some form around three thousand years ago. However, it is disputed whether in ancient times it was more of a kind of functional differentiation in the meaning of Karl Jaspers, whereas since colonial times it became a separation boundary between the various groups. I assume that the colonial rulers transformed an existing variety of functional differentiations of identities into strictly separated castes for reasons of securing their rule. As in other colonial rules like in Africa, the colonizers were puzzled by the plurality of social groups, their ability to change from one group to the other and transformed social groups based on functional differentiation into castes and classes to facilitate their own rule. Overcoming the caste system thus involves overcoming colonialism.