The Peninsula Foundation organised a webinar titled ” World Order Turmoil: The Reality of American Empire” on the 19th of January 2024. The main talk was given by the Chief Guest Jermey Kuzmarow and further comments was provided by the Discussant, Mohan Guruswamy. The event led to excellent discussions with critical comments from both the speakers. The discussions were moderated by Air Marshal M Matheswaran, President-TPF.

Jeremy Kuzmarov is Managing editor of CovertAction Magazine and author of five books on U.S. foreign policy. His website can be accessed here. Mohan Guruswamy is our Governing Council member and a Distinguished Fellow and a prolific writer on economics, security, and geopolitics.

Given below is the text of jeremy Kuzmarow’s talk, along with questions and answers.

(Source: tunnelwall.blogspot.com)

In September, I attended a talk sponsored by the Tulsa Committee on Foreign Relations by an inside-the-beltway pundit named Ali Wyne, a former senior fellow at the pro-NATO Atlantic Council and David Rockefeller fellow at the elitist Trilateral Commission.

Wyne told the audience in so many words that the sun had not yet set on the American empire; that the Biden administration was outmaneuvering the evil Putin in Ukraine; and that the U.S. was still a beacon of hope for the rest of humanity.

Toward the end, Wyne personalized the talk, discussing how his family had migrated to the U.S. from Pakistan with nothing, and that through hard work he was able to achieve the American dream.

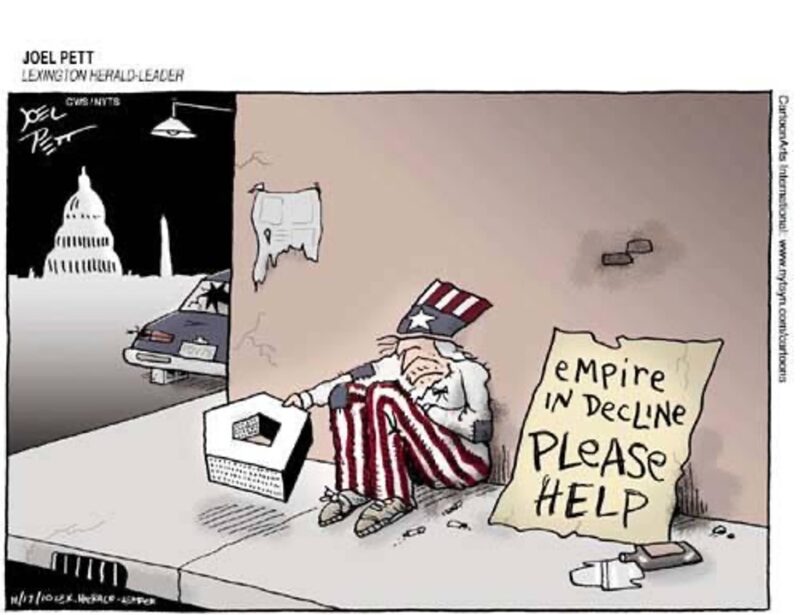

But Wyne seemed oblivious to the fact that that dream is increasingly unreachable for the majority of people in an increasingly stratified society marred by a decline in civilian manufacturing and public services and skyrocketing education costs.

Wyne also failed to point out that the American dream historically was achieved at the expense of Third World nations that were looted by U.S. corporations, and by endless wars that killed millions of people.

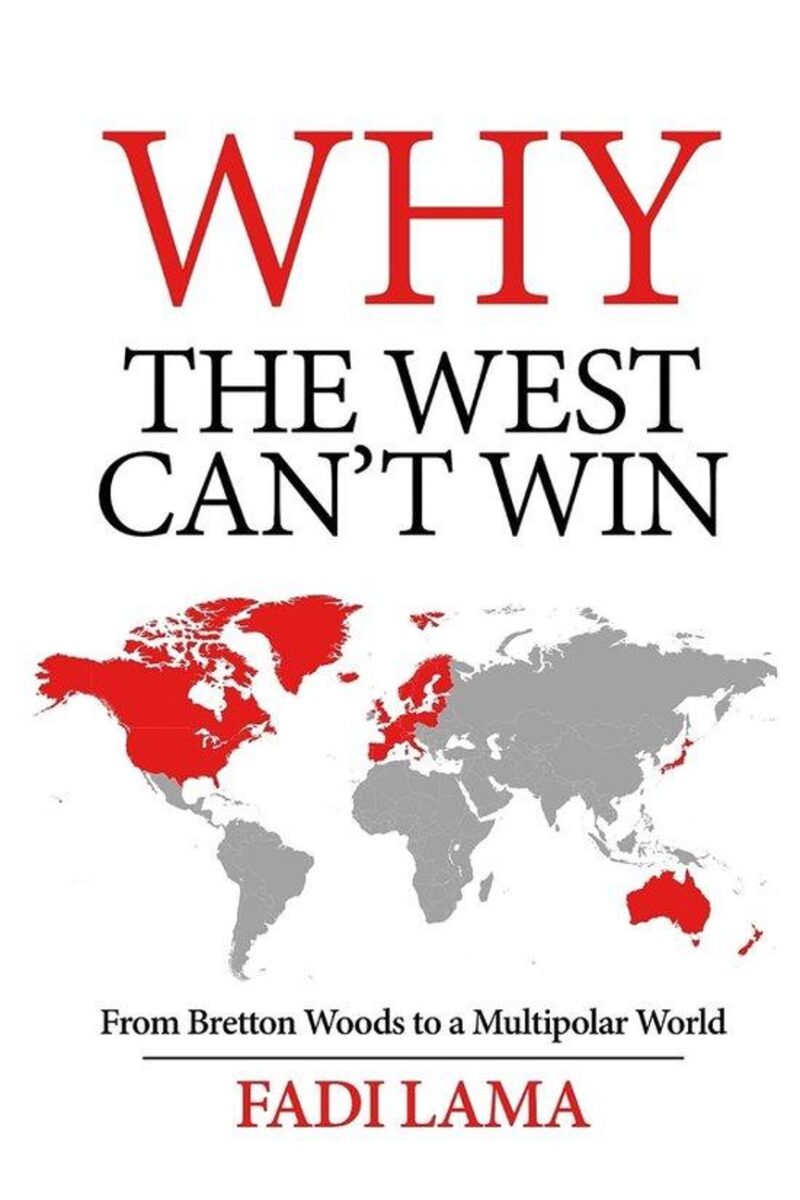

Wyne’s delusional worldview is underscored in a new book by Fadi Lama, Why the West Can’t Win: From Bretton Woods to a Multipolar World (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2023), which shows that the American Century has ended and that a new multipolar world order has been established in which economic dynamism lies primarily in the East.

Lama is an international adviser for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and geopolitical consultant with a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech).

He points out at the beginning of his book that in 1500, prior to the era of Western colonialism, there was a relatively fair political-economic world order with a close equilibrium between population and wealth generation. But by the end of World War II, the West accounted for only 30% of global population but 60% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

When many colonized nations gained their independence, the West imposed a neo-colonial framework that enabled their resources to be exploited by Western multinational corporations.

Some countries on the front lines of the Cold War, such as West Germany, Japan and South Korea, were allowed unhindered development as part of a geopolitical strategy designed to keep them within the Western orbit and curb the advance of Communism. However, being pseudo-independent states, when the political necessity was removed, they were cut back to size.

The liberation of China in the 1949 Communist-led revolution (an event known in the U.S. as the “loss of China”) was a historical turning point that began to reverse the Western monopolization of wealth and power and set the stage for the re-empowerment of the Global South.

By 2017, China—known as the “sick man of Asia” in the 19th century following its de facto colonization of Great Britain following the Opium War—was the world’s number one economy with its real goods production amounting to 24% of global real goods production.

Under CCP leadership, China regained its sovereignty and lifted 770 million people out of poverty, with homelessness now being practically non-existent.

According to Lama, China’s staggering economic success resulted from a centralized political system in which commercial banking was dominated by the public sector. Central bank financial and monetary policies were further put under the control of the Chinese government, which implemented policies serving the national interest rather than those of the Western financial oligarchy.

China’s economic success contrasts markedly with the growing economic stagnation in Western countries and the U.S. resulting from the neo-liberal economic model in which the private sector is elevated above the public sector.

By 2014, the top 0.1% in the U.S. owned as many assets as the bottom 90%, an obscene inequality ratio accompanied by a dramatic rise in poverty, which had been reduced massively in China under more socialist-oriented policies.

China’s superior state-centric economic model is currently being followed by Russia which has withstood record U.S. sanctions under Vladimir Putin’s leadership through a renewed commitment to economic autarky (self-sufficiency) and investment in local industries and technologies.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, U.S. strategic planners saw a golden opportunity to reduce Russia’s status to that of a fourth-rate power and to enable the plunder of its bountiful natural resources.

The overzealous policies backfired, however, pushing Russia into alliance with China that signifies the birth of a new multi-polar world order that holds the potential to restore the global economic parity from 1500—before Western colonization took root.

Lama emphasizes the fact that Russia now provides food aid in Afghanistan and Africa and fertilizer to poor countries, and has forged growing relations with both China and Iran, the latter having gained independence from Western colonial tutelage in 1979 when the Shah was overthrown.

Lama finds significant economic synergy and growing win-win cooperation in the economic, cultural, scientific and military fields between China, Russia and Iran, which he says are “de facto allies in the struggle for a ‘Fair World.’”

Russia and China today are leading the way in space exploration, clean energy technologies as well as cutting-edge missile technologies at a time that U.S. weapons systems are proving to be extraordinarily costly and inefficient owing to a Byzantine Pentagon contracting system and under-skilled workforce due to the skyrocketing costs of higher education.

Today’s shifting power balance can be compared with 1997 when “‘the empire’ had control over three of the top four energy reserves: Venezuela was a U.S. vassal, Russian energy resources were under control of the Money Powers (Western financial oligarchs) via their proxy Russian oligarchs, and Saudi Arabia was a compliant U.S. tributary. Of the top four, only Iranian reserves were out of the Money Powers’ control.”

By 2022, Lama writes, “the Empire had lost control of the top three reserves, Venezuela, Iran and Russia, while Saudi Arabia is no longer as compliant as it was in 1997.”

What happened in the interim was a period of heightened military intervention and imperial overreach resulting in a counter-mobilization that signifies the end of the era of Western empires dating back to the 16th century.

Bretton Woods: From Military to Financial Colonialism

The imperial framework after World War II was established through the Bretton Woods economic system, which Lama says was designed to “lock countries into a financial structure controlled by the West.”

Lama writes that this structure “requires central bank governors be independent of their governments, but dependent on rules established by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), at the top of the pyramid in the Bretton Woods system.

Established in 1930 to handle reparations payments imposed on Germany at the Versailles Conference after World War I, BIS had helped finance Hitler’s rise to power and was owned by central banks, setting policies for them that directly influenced the global economy.

Franklin D. Roosevelt had proposed liquidating the BIS due to its cooperation with Nazi Germany, though the resolution that he sponsored to that effect at the July 1944 Bretton Woods Conference at which the post-World War II monetary and political global structure was being set, was revoked after Roosevelt’s death.

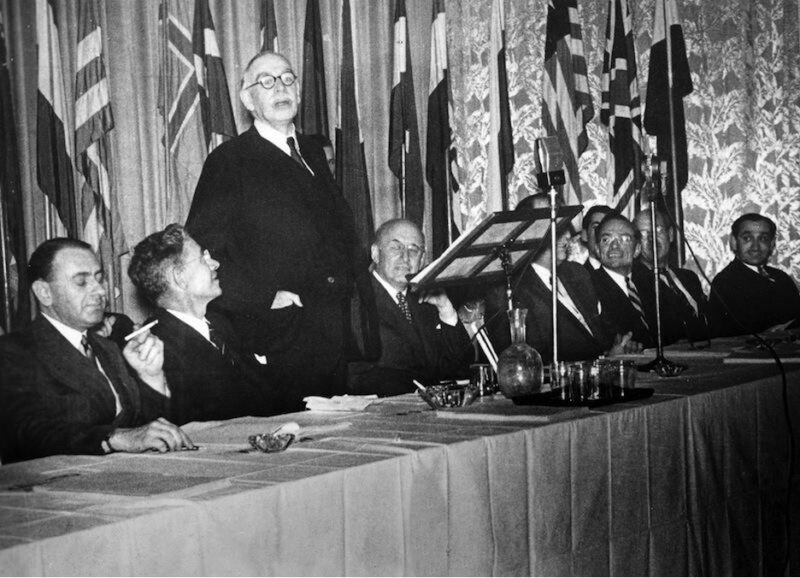

John Maynard Keynes addressing the July 1944 Bretton Woods Conference in New Hampshire. [Source: centerforfinancialstability.org

According to Lama, when some newly decolonized countries tried to adopt an alternative economic arrangement to Bretton Woods, their leaders (Togo’s Sylvanus Olympio, Egypt’s Nasser; Indonesia’s Sukarno; Democratic Republic of Congo’s Lumumba; Iran’s Mossadegh; Ecuador’s Jaime Roldos; Panama’s Omar Torrijos) were eliminated by wars, coups or assassinations [over a 25-year span].

Economic hit men would descend on developing countries offering loans for infrastructure projects whose real purpose was to plunge these countries into debt so they would become dependent on foreign creditors and their economies could be restructured along neo-liberal lines and in the service of multi-national corporations.

A pillar of the Bretton Woods system was that the U.S. dollar was established as the international trade currency, which was convertible into gold at the fixed rate of $35 per ounce of gold.

With the decline of U.S. competitiveness in the 1960s, the Nixon administration froze the convertibility of the U.S. dollar in gold and, instead, made it convertible to oil, provided that oil was sold only in U.S. dollars.

This led to a dramatic increase in the price of oil and petrodollar arrangement with Saudi Arabia by which the U.S. provided military protection and weapons to the Saudis in exchange for the promise of them trading their oil in U.S. dollars and using income from oil to buy U.S. Treasury bills. Interest on these sales was then spent by the U.S. Department of the Treasury on infrastructure projects in Saudi Arabia to be executed by U.S. companies.

The fact that other countries had to hold reserves in U.S. dollars to cover their oil imports allowed the U.S. to incur high trade deficits bred by deindustrialization in the neo-liberal era without causing a depreciation of the U.S. dollar.

However, this is no longer sustainable in the long term and Russia and China are spearheading a shift in the global economy by which oil and other commodities are no longer being traded in U.S. dollars, ushering in the end of the American Century.

The Money Power

Lama’s book includes discussion of the growth of the Western financial oligarchy, or what he calls the Money Power, who are the major shareholders of the leading hedge funds (BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street) and have become the absolute rulers over society.

According to Lama, the Money Power is well placed to control elections in Western democracies and control mass media in all its forms, print, TV and social media platforms.

They support free trade agreements designed to usurp what little is left of national sovereignty and a neo-liberal vulture economy in which all aspects of the economy are privatized in order to maximize corporate profits.

The U.S. decline has been fueled by the Money Power’s recognition that maintaining a strong manufacturing base was no longer necessary when trade deficits could be offset by currency manipulation owing to Nixon’s convertibility of the U.S. dollar to oil and the trade in oil around the world in U.S. dollars.

The U.S. economy is increasingly dominated by the financial sector which flourishes at the expense of other vital economic sectors, leading to the high wealth concentration and impoverishment of society made worse by austerity measures entailing cutbacks in social and other government services.

Russophobia, Sinophobia and the End of an Era

The intense Russophobia cultivated in the U.S. media over the last decade is the result of the Money Power’s lust for Russia’s immense wealth, which it was starting to gain access to in the 1990s before Vladimir Putin reasserted national control over Russia’s economy.

The anti-Russia propaganda has had the greatest impact on the educated classes, as 77% of Americans with post-graduate degrees considered Russia an enemy in a March 2022 poll, compared to 66% with high school education or less.

Russophobia has been combined with an ascendant Islamophobia and Sinophobia, whose purpose is to mobilize public support for confronting the troika of powers (Russia, Iran and China), which threaten Western hegemony.

According to Lama, if a date were to be identified for the end of the U.S. empire, it would be January 8, 2020, when Iran avenged the assassination of General Qasem Soleimani by attacking a U.S. air base in Iraq and displaying Iran’s weapons capability.

Afterwards, the U.S. Central Command (Centcom) significantly relocated its headquarters from Doha, Qatar, just 125 miles from Iranian shores, to safety in Tampa, Florida.

While the current U.S. war in Gaza has created a renewed pretext for expanded U.S. military intervention in the Middle East, Lama’s book makes clear that the U.S. could not win a war against Iran for regime change.

Contrary to Wyne’s analysis, the U.S. has also been outmaneuvered in Ukraine, whose army is in a state of disrepair after a failed counteroffensive. It is further being outmaneuvered by China, which is winning hearts and minds through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that provides low-interest loans to countries for infrastructural development with no strings attached.

In sum, the Great Game for world domination appears to be up and the Money Power has lost. That is why they are behaving so erratically in manufacturing crisis after crisis as they desperately attempt to sustain a fading world order defined by profound inequality and injustice. For the rest of my talk, I will try and further answer some of the questions that were posed prior to the seminar:

Question 1) This dealt with consistent U.S. war making as a tool in which the US tried to sustain its hegemony, and growing pushback with the rise of BRICS, Shanghai Cooperation Organization and Rise of China? How will all this shape the future world order?

Answer: There is the threat of a world war breaking out provoked by the U.S. as the U.S. cannot tolerate geopolitical competition or being relegation to a second rate power, and will respond violently—as it is already doing. Currently, the U.S. is provoking wars simlutaneously with Russia, China and the Middle East, with catastrophic consequences already for the people of Ukraine, Russia and Gaza. The great Australian journalist John Pilger produced a documentary in 2016 warning about the U.S. military buildup in the Asia Pacific and coming war with China, which would be catastrophic for everyone involved.

It is instructive to look back in history to the 1930s when Japan challenged U.S. and Western empires in the Asia Pacific with the establishment of the Greater Economic Co-Prosperity Sphere. This challenge and effort by Japan to establish an alternative yen bloc in Southeast Asia and to supplant the Western colonial powers led directly to the Pacific War. Records from the time reveal how the U.S. manuevered Japan into firing the first shot (an explicit goal of U.S. policy as outlined by Secretary of State Henry Stimson) by imposing a naval buildup in the South China sea and crippling oil embargo that threatened to cut off Japan’s oil supply and undermine its empire in the Asia-Pacific.

There is evidence that FDR knew about the impending Pearl Harbor attacks but allowed them to take place because the American public would only support military intervention if America were attacked and the attack was made to look like a sneak attack by a dastardly enemy.

History could easily repeat itself today; the U.S. military is in fact preparing for war in the Asia Pacific; building a new military base in Micronesia in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, and training soldiers in jungle warfare in Hawaii while studying military battles in the Pacific War, like the Battle of Guadalcanal.

Gen. Charles A. Flynn, the commander of U.S. Army Pacific, was quoted in The New York Times stating that China had been on “an incremental, insidious and irresponsible path for decades.” Now more than ever, the “total Army,” he said, needs to prioritize relevant Pacific experience.

U.S. soldiers being trained to fight a 21st Century Pacific War—this time against China. [Source: nytimes.com]

After provoking a war with China, like with Japan in World War II, the U.S. would surely make it look like China started it and that it was somehow innocent. This has been a feature of US imperial wars going back to the era of the Indian Wars.

Question 2: The first half of the 20th century was essentially a contest of empires. The two World Wars were fundamentally European wars or a contest of colonial empires. While the European empires were destroyed, the gain was for the U.S. as it emerged as the most powerful actor.

Answer: Agreed. I would add that the U.S. defeated the Japanese empire in the Pacific theater of World War II, which enabled the U.S. to establish a chain of military bases in the Asia Pacific as a linchpin of U.S. imperialism. U.S. strategic planners had long considered the Asia Pacific key to world domination because of its economic vitality and rich resources and geography and this is why the U.S. cannot accept any rival powers there, including Japan, and now China.

Question 3: Did the U.S. foresee this and plan its rise to a position as the pre-eminent power ensuring the destruction of the European powers?

Answer: Yes, absolutely. As one example of dispacing European empires, I was just reading a book about U.S. policy in Congo in the 1960s by David Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention. The book showed how U.S. mining tycoons (Maurice Templesman and Harold Hochschild) came to oppose Belgian colonialism so American corporations could replace Belgian ones in controlling and profiting from Congo’s lucrative mineral wealth. Templesman and Hochschild financed CIA front organizations and supported the murder of Patrice Lumumba who wanted to nationalize Congo’s mines after independence. They cultivated very close ties with Joseph Mobutu; Lumumba’s replacement and murderer, who cultivated the image of a Pan-Africanist devoted to African culture, but who sold out Congo and its economy to foreign interests. The CIA funded Mobutu’s security apparatus so he could crush a secessionist movement in the diamond rich Katanga province backed by the Belgians. The goal was for Mobutu to consolidate his control over Congo and for U.S. corporations to take over the mines from Belgians in Katanga. Here is U.S. neocolonialism at work, and muscling out of the Europeans.

Question 4: The U.S.-led post-1945 world order rests on its control of the three pillars – political, economic, and security ( Allies/Vassals, Economic Control through Bretton Woods systems + USD as the global reserve currency, and the UN Security Council+NATO). Is Western Europe an Ally of the US or is it an unequal relationship?

Answer: I would say its an ally of the U.S. to a point, as we see from the example of the Belgians in Congo. Many Europeans are starting to question alliance with the U.S. and whether the US has the best interests of European countries in mind. The U.S. involvement in Ukraine and destruction of the Nordstream II pipeline, for example, has been deterimental to European economies, including especially that of Germany that relied on cheap Russian natural gas imports. With the destruction of the pipeline, they were forced to purchase natural gas at a much higher cost from the Middle East and from U.S. natural gas suppliers in Texas and elsewhere who were financing politicians in the U.S. that supported the copious military aid to Ukraine along with the weapons contractors. European countries historically benefited from trade with Russia, so the war in Ukraine has generally hurt their economies and it is not clear for how much longer their populations will put up with this and just go along with the New Cold War.

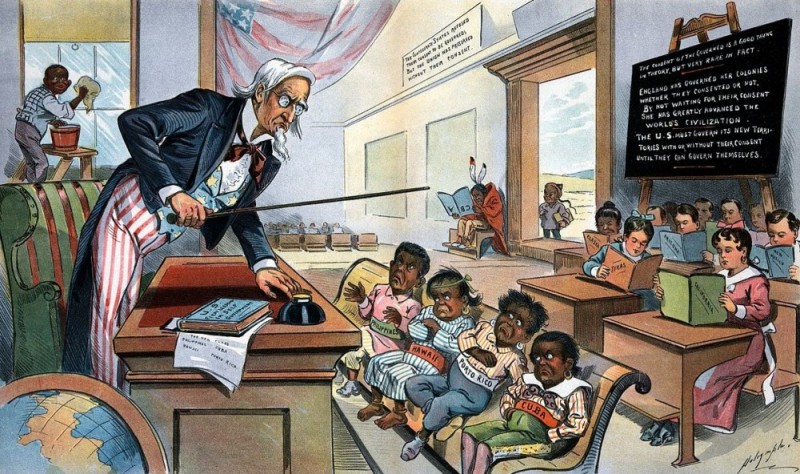

Question 5: Decolonisation was superficial as the U.S.-led West retained much of the colonial and imperial controls. Is it right to say that the U.S., in effect, has been an expanding empire since the American-Spanish War? The Cold War was a check on the American expansion.

Answer: Decolonization was indeed superficial as the U.S. used clandestine and sometimes not so clandestine means toinfluence and control postcolonial leaders across much of the Third World and to sustain neocolonial economic relationships where Third World countries exported raw materials to the West and purchased products that were manufactured there, or had their resources owned and controlled by U.S. corporations.

I would suggest that the U.S. was an expanding empire from the formation of the country. Historian Richard Van Alstyne wrote an important book in 1960 entitled The Rising American Empire. The book shows how the American founding fathers all conceived of the U.S. as an empire and had ambitions of eclipsing the British and Roman empires at their height. Van Alstyne also addresses how the pacification of the Native Americans and takeover of their resources and land and massacre of those who resisted previewed what the U.S. would do to other peoples around the world.

As far as the Cold War, my book, The Russians are Coming, Again with John Marciano shows that rather than being a check on U.S. expansion, the Cold War served to validate heightened U.S. intervention across the Third World under the pretext of fighting and combatting communism. In fact the real communist threat, as Noam Chomsky has emphasized, was a threat to U.S. business interests and ability to encourage development of an alternative state-centered model of governance that would prevent corporate pillage and the kind of neoloconial arrangements that prevailed quite widely in this period and beyond.

Question 6: The end of the Cold War and American unipolar dominance unleashed the push for the American Empire—through GWOT and a series of wars.

Answer: Absolutely: We have the U.S. empire on steroids with the Global War on Terror. It has given a pretext for the U.S. to invade and bomb many Middle-Eastern countries. And it has been totally ridden with contradictions, as the U.S. has supported leading terrorist states like Saudi Arabia and committed large scale terrorist acts based on standard definitions of terrorism as acts of violence targeting civilians with the purpose of affecting a political goal or political change.

Source: goodreads.com

Question 7: NATO Expansion – conflict with Russia and anti-China strategy – a clear case of imperial overstretch and suicidal?

Answer: Yes I think so. Back in 1996, George Kennan, the father of the containment strategy and original Cold War, warned about NATO expansion, stating: that NATO expansion would amount to a “strategic blunder of epic proportions” and the “most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold War era,” as it would “inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies in Russian opinion, restore the atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations,” and “impel Russian foreign policy in a direction decidedly not to our liking.”

Kennan’s prediction proved to be true and look where we are today: in a new Cold War, with the U.S. having torn up the arms control treaties of the 1980s; initiated a proxy war with Russia that could lead to a full-blown war between the two countries and nuclear conflict. If the latter transpires, the NATO expansion surely will have been suicidal. Already it is diverting badly needed resources towards the military and a senseless new arms race, much like in the original cold war, where it produced heavy deficits and Third World type living conditions in the U.S. with astronimical inequality levels, underfunded edcuation and health care system, and abysmally poor public services, including in areas like mental health treatment, and programs to assist the homeless. One consequence is the extremely high crime rates in the U.S. and overcrowded prisons.

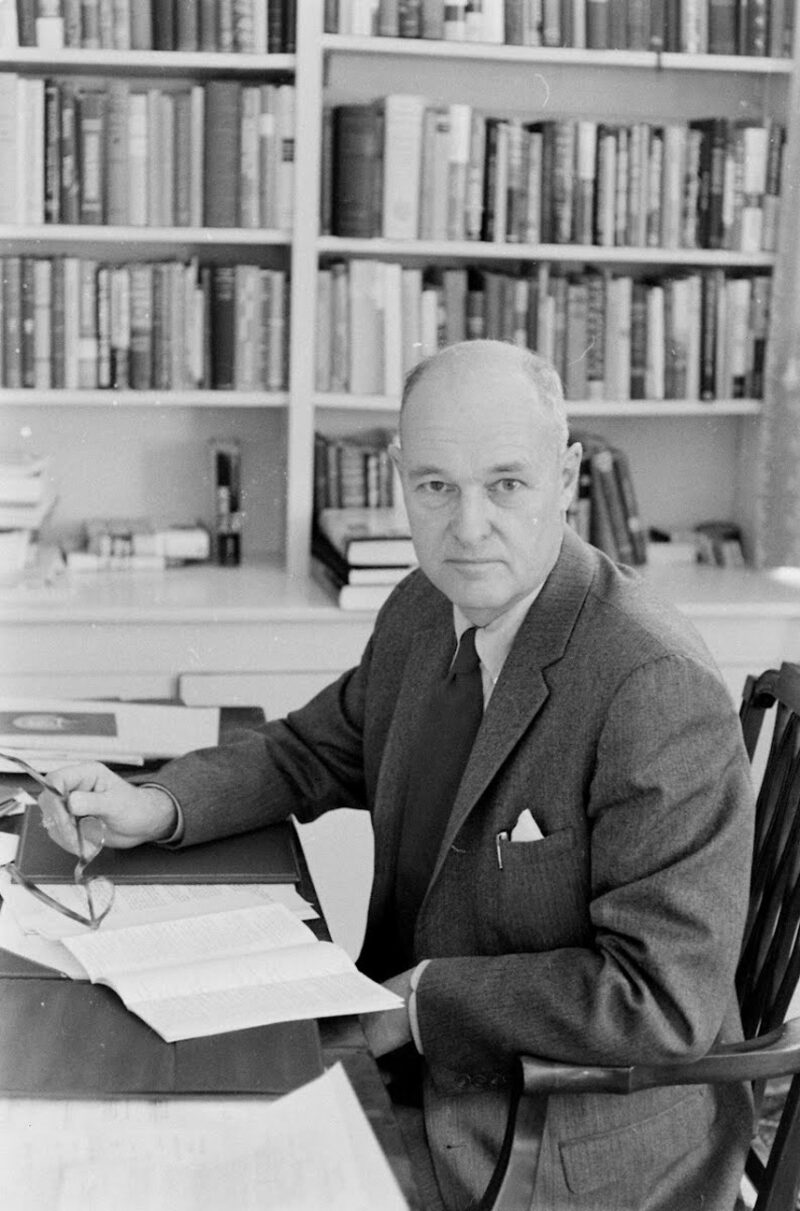

George F. Kennan: if only U.S. leaders in the 1990s and 2000s had listened to him [Source: artsandculture.google.com

As far as China, the provocations by the Biden administration may be even more insane than with regards to Russia, as a) the U.S. depends on Chinese purchasing of U.S. debt; b) the U.S. economy is quite dependant on China’s; and c) China has superior military technology capabilities that would give it the edge in any war with the U.S.

Charles Freeman is a retired diplomat who served as Nixon’s translator when he famously visited China in theearly 1970s to reestablish U.S. diplomatic relations during the Cold War. Freeman told me when I interviewed him that China was in no way a military threat to the U.S., but the U.S. sees it as a threat because its economy has been growing and slowly surpassing that of the U.S. The U.S., however, should not view China as a threat of any kind, and should consider its economic growth an opportunity for the U.S. if it tried to harness China’s economic growth to its own. This would mesh well with the win-win strategy advocated for by Chinese Premer Xi Jinping in which China and the U.S. would cooperate to mutual economic benefit.

Charles Freeman [Source: globaltimes.cn]

Charles Freeman [Source: globaltimes.cn]

Instead, the U.S. has sought to a) encircle China militarily, b) arm Taiwan to the teeth in violation of the “One China” policy and incite Taiwanese separatist elements, c) try and undermine Chinese interests throughout Southeast Asia, and d) provoke it by launching drone surveillance missions over its borders and in Chinese controlled waters off Taiwan, and e) sailing U.S. naval ships in Chinese waters.

This is in addition to a) the propaganda directed against China in the U.S., b) the persecution of Chinese scientists; c) support for separatist elements in Xinjiang and Tibet; and d) the waging of an economic war on China and efforts to sabotage China’s economy—a policy that had been pursued by the FDR administration against Japan that directly provoked war with it.

Question 8: Are current wars in Ukraine and Gaza—a sign of major turbulence in the World Order?

Answer: Yes absoutely. These wars were both easily avoidable and were a direct result of U.S. foreign policy and its extremism.

- In the case of Ukraine, the U.S. was intent on using Ukraine as a battering ram directed against Russia. The U.S. orchestrated the 2014 Maidan coup and empowered and armed far right, Russophobic elements who triggered the war with Russia by a) attacking the ethnic Russian population in Eastern Ukraine; and b) reneging on any commitments in the Minsk peace agreements that would have given greater autonomy to the Luhansk and Donetsk provinces. The U.S. aim was similar to Afghanistan in the 1980s where they wanted to draw the Russians into a military quagmire and trap and discredit Putin and cripple his regime by ratcheting up economic sanctions against him (which it was believed would create disaffection with his rule and trigger a movement for regime change). This strategy was born of desperation because Putin was succeeding in strengthening Russia and blocking the neoconservative designs to control Eurasia and its rich oil and gas reserves, which was only possible with a weakened Russia.

- Gaza: The U.S. has long used Israel as an outpost of its power in the Middle East, recently establishing secret military bases in the Negev. The neocons in Washington have long sought regime change in Iran and see Israel as their vehicle to help achieve that. They also wanted regime change in Syria and to ensure Israeli control over the Golan Heights, where oil reserves have been discovered. U.S. weapons have emboldened hardliners in Israel and enabled Israeli aggression in Gaza and now Lebanon with disastrous human costs for the civilian population that people are comparing to a new Holocaust.

Question 9: With the rise of China, India, and the BRICS—is this a Power Transition moment?

Answer: Yes. We are seeing major historical changes in real-time. China’s achievements through the One Belt, One Road initiative were so impressive they led to a copycat effort by the Biden and Boris Johnson admiinistrations that never really got off the ground. The SCO is enabling countries also to get around the World Bank and IMF by offering loans with no strings attached. China’s rise is epitlmized by its trading alliance with Russia and influence throughout Africa, where China is clearly winning the Great Game. While Chinese labor practices may be bad in many places, China is bringing tangible benefits to African countries through the building of impressive infrastructure, whereas all the U.S. offers is drone bases and IMF structural adjustment programs that push economic austerity measures and reinforce social inequality.

Question 10: Is this a sign of the end of Western dominance of the last 500 years?

Answer: I believe that yes, we are seeing major historical shifts. It may take some more time as empires often do have lasting power and can linger on even when their legitimacy has been eroded, but change is coming about.

Question 11: In its entire history, the USA has been at war for all but 15-20 years. Is the USA a war-mongering state?

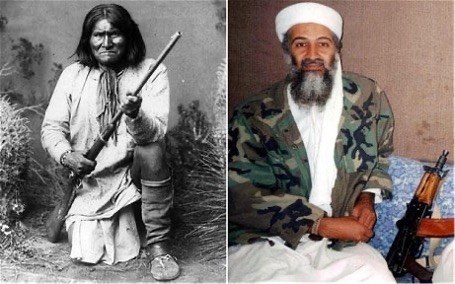

Answer: Sadly, yes. It goes back to the founding of the country as a settler colonial state rooted in the military conquest and genocide of the Native Americans. The colonial mentality is so deep that the U.S. names a lot of its weapons systems after native tribes that were vanquished, like the Apache helicopter for example. The Operation to kill Osama bin Laden was called Operation Geronimo after the Apache chief who was vanquished in the 19th century. Noam Chomsky once asked; imagine the nazis had won World War II, and named weapons: “gypsys” and ‘Jews.”

[Source: telegraph.co.uk]

This reflects something rotten at the core of imperialism and a deep imperial mentality that is hard to vanquish and is passed on generation after generation. This mentality and the war like culture in the U.S. is seen in a hero worship of soldiers and the military at sporting events, and in the denigration and marginalization of peace activists in popular and intellectual culture.

That the military culture is a largely top down phenomenon though should be emphasized as since Vietnam, the U.S. government has dared not reintroduce the draft, lest it face a societal revolt remniscent of the 1960s counter-culture movement. So a lot of Americans see through the lies and are not so hawkish—that’s why the government has to distance the public from the wars; lie to them repeatedly about what they are all about; and develop new technologies and AI that could ensure a reliance on machines in fighting wars rather than the American people who often see through the lies and will protest an unjust war—particularly if there are a large number of U.S. ground troops potentially being put in harms way (like in Vietnam).

Question 12: What is the future of 21st century world order? Barry Posan says the era of Superpower is over. Has the multipolar world emerged? what would be its shape?

Answer: I think we are indeed seeing the birth of a new multipolar world order in which the center of economic power in the world increasingly lies in the East and in which China is a powerhouse and Southeast Asia is a key motor of economic growth in the Global economy. The U.S. is sliding more towards authoritarianism and potentially even a civil war, and may be further weakened by domestic unrest as it loses its economic supremacy and the U.S. dollar ceases to be a main currency of global trade. U.S. military interventions may focus more on South America and Mexico (which some Republicans want to bomb now to stem the immigration tide) and the U.S. army may have to be deployed more often to contain domestic unrest and right wing estremists/neofascists and to control armies of homeless people who are a product of a failed economic model.

Related to the last question about U.S. adaptation to the new realities, a great danger is that the U.S. won’t accept reality, and will attempt to violently reimpose its hegemony, triggering a new Pacific War or world war that would result in millions of deaths.

The recent escalation of conflict in Ukraine and the Middle East as well as U.S. saber rattling towards China and over Taiwan, makes this threat all too real and ominous.

Feature Image Credit: iai.tv