Are we witnessing the end of globalisation and the rise of economic nationalism? Who is responsible for this state of affairs? For many, the villain is clearly the US and its allies in the West. The reason is the rise of China as the world’s manufacturing and technology superpower. China is beating the West at its own game, and the US is shaken by the visible signs of the end of its hegemony and the dominance of the West. Globalisation is being throttled by the West in a futile attempt to end China’s rise. The result will be catastrophic for the Global South in its aspirations for accelerated development. Former Venezuelan ambassador and Princeton scholar Alfredo Toro Hardy analyses what he sees as the sunset of globalisation.

– Team TPF

Economic globalisation was the offspring of the neoliberal ideology that prevailed after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The globalisation process took off in the mid-nineties, as was identified by the firm support given to it by leaders such as Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, particularly the former, who commanded the world’s largest economy.

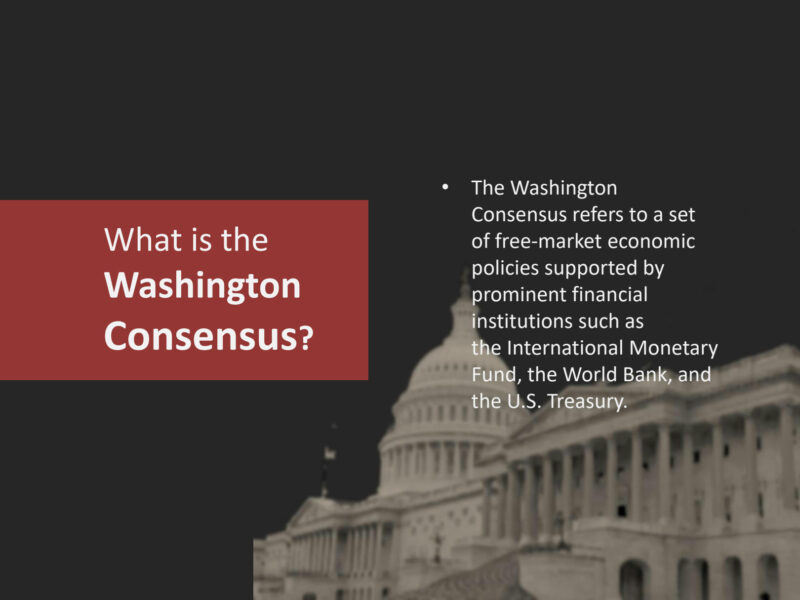

Its most emblematic expressions would be the Washington Consensus, the creation of the World Trade Organization in 1995, and China’s entry into these organisations in 2001. The first resulted from the convergence of positions between the U.S. Treasury Department and International Financial Organizations based in Washington. It would translate into a ten-point recipe called to set in motion the economic liberalisation of distressed and closed economies, chiefly the previous communist ones. The second involved the global homogenisation of rules in matters as diverse as manufacturing, agriculture, services, labour standards or intellectual property, as well as the abandonment by its members of industrial policies and protectionism. The third represented the insertion into the global labour market of more than a billion human beings whose working costs were but a fraction of those in developed countries. This would be accepted and even promoted by the United States under the assumption that a China open to the world’s economy would eventually open itself to the values of liberal democracy as well.

The importance of neoliberal ideology, as a determining factor of this process, would be key. As a matter of fact, for a long time the leading force in the world economy, America’s economy, was characterised by its industrial policies, protectionism, and vertical integration of its corporations. The federal government’s industrial policies became a catalyst for economic development, either through direct investments and engagement or through incentives for the private sector to follow a particular course of action. The countless products and services incorporated into the American technological repository resulting from NASA’s R&D efforts exemplify these policies. They still represent the broad shoulders on which the country’s private technological sector stands. Protectionism expressed itself through tariffs and non-tariff barriers to protect domestic production from foreign competition. Vertical integration, on its part, involved direct control by U.S. corporations in their production and distribution channels. Hence, outsourcing did not figure in their strategies. It is worth adding that even President Reagan, despite his deregulatory crusade, supported his country’s industrial policies and imposed protective barriers against Japanese competition (Foroohar, 2022).

Globalization in question

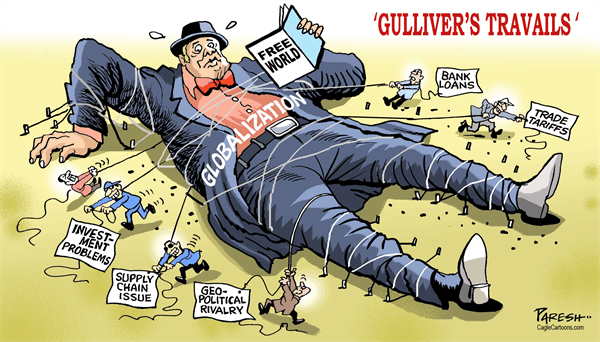

For decades, globalisation has represented an unchallenged paradigm. Under its course, China reached the anteroom of world economic supremacy, numerous cheap labour economies, particularly in Asia, emerged strongly, and large corporations relying on the revolutions in information technology, communications and transports outsourced and dispersed their production and services (again mainly in Asia). Actually, it was in the emerging Asian countries where, in nine of every 10 cases, the great beneficiaries of globalisation were concentrated. Moreover, it was estimated that between 2020 and 2030, the global middle class would jump from 3,300 million to 4,900 million people, with 80% of that jump taking place in Asia (Milanovic, 2018, p. 19; OCDE, 2010). However, for some time now, globalisation has been under serious questioning. Among the reasons behind this, the following should be outlined: the emergence of powerful populist movements in the Western World; climate change distortions upon trade and the impact on climate itself, resulting from maritime trade over long distances; and economic and political nationalism in China.

Populism is, to a large extent, directly related to the immense social upheavals caused by the massive outsourcing of jobs to the cheapest labour economies. In 2000, Clinton predicted that globalisation would allow the export of products without exporting jobs. Exactly the opposite happened, though, seriously affecting the social fabric of the United States and its European counterparts. This significantly eroded their democratic systems. Climate change, with hurricanes, floods, and other incidents, has increased the risk of global supply chains, resulting in annual revenue losses of up to 35% for companies. (McKinsey and Company, 2020).

Conversely, the massive mobilisation of supertankers worldwide generates up to 14% of the total greenhouse gas emissions affecting the planet. (Prestowitz, 2022). Indeed, “the ultimate buyer [of final products] remained an ocean or a continent away” (O’Neil, 2022, p. 113). In addition, contrary to what American promoters of China’s emergence had suggested, the country’s economic prosperity has led to an increasingly nationalistic and authoritarian model. Far from getting closer to U.S. values, China has emphasised its economic nationalism and geopolitical aggressiveness within the context of a growing rivalry with the United States.

The triggering elements

However, even if disappointment with globalisation continued to grow, the triggering elements that would end up clearly tilting the balance against it were still missing. COVID and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine took care of it. Twenty trillion U.S. dollars in goods rely on global supply chains. Especially so as the disaggregation of production translates into millions of components, parts and final manufacturers moving in every direction. (McKinsey and Company, 2020). This vertiginous dissemination of productive processes led to unexpected, sudden, and massive disruptions during the pandemic. As a result, global economic interdependence choked. The endless Zero COVID policy implemented in China, the geographic nerve centre for global trade, exponentially aggravated this situation. The result was none other than inflation that brought to mind the seventies and has not yet been controlled.

This was joined shortly afterwards by the impact of the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. One that not only disrupted vital energy and food supply chains but fundamentally brought geopolitics back to the global scenario through the main door. As if the emerging Cold War between China and the U.S. had not already been enough to undermine faith in globalisation, events in Ukraine made security the central component of the international order. It was a sort of fall of the Berlin Wall in reverse. One that brought down the relevance of economics and propelled that of politics. Olaf Scholz’s “global zeitenwende” clarified that a new strategic culture and national strategy would become his country’s new priority (Scholtz, 2023). Under such circumstances, placing economic security in distant and potentially hostile hands was no longer a rational option.

Back to the past

Not surprisingly, the United States began reverting to policies that preceded globalisation. That is, to industrial policies, to protectionism, and the vertical integration of its corporations. Indeed, before losing the House of Representatives to Republicans in November 2022, Biden’s Democrats passed several laws that embody industrial policies. A perfect example is the so-called energy revolution, with 490 billion dollars being involved in incentives to guide private investment towards generating clean energy sources. It also allowed the federal government to intervene in medicine prices through direct negotiations with the pharmaceutical industry. In the same direction went the laws that stimulated competitiveness and innovation, the superconductors industry, and infrastructural development. In parallel, the “Buy American” policy, subsidies to the domestic industry, and the maintenance of the tariffs imposed by Trump represented an evident protectionist impulse. Meanwhile, American corporations, in tune with these policies and in reaction to the risks of dismembering their production and services on a global scale, are opting for vertical integration and direct control of their activities. This implies, by its very nature, a production centred on the local or the regional.

Getting back home

All of the above factors contribute to industries’ onshoring and supply chains. In 2021, of the 709 large U.S. manufacturing corporations consulted, 83% responded that they would very likely or probably return their production operations to the United States. (Ma, 2021). Numerous leading American and foreign corporations are opting to produce in the U.S. to benefit from the new incentives put in motion by the Biden administration. This list includes, among many others, Intel, GM, US Steel, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSMC), Toyota, Samsung and Micron Technology. The amount of their investments, in tens of billions of dollars in many cases, speaks for itself. The motivation behind this impressive move was well reflected in the words of the larger-than-life founder of TSMC, Morris Chang: “Globalization and free trade are almost dead and unlikely to return”. (Cheng, 2022; Doherty and Yardeni, 2022). However, together with this on-shoring move, there are also parallel movements of near-shoring or friendly shoring nature, where manufacturing and supply chains are being circumscribed to neighbours or traditional allies that do not represent a security risk. With the world’s largest economy becoming protectionist, it will be difficult for globalisation to retain its influence, especially as Europe rapidly evolves in the same direction.

Globalization last hope

Until recently, an area of globalisation seemed to be relatively protected from these kinds of upheavals: the digital ecosystem. According to a 2016 report, the rapid flows of international trade and finance that characterised the 20th century appear to have flattened (…), yet globalisation has not reversed. Indeed, digital flows are growing very quickly.” (McKinsey Global Institute 2016). However, a few months ago, Brookings published a highly pessimistic report regarding the future of this sector. According to it: “Historically, the arrival of the global web created an opportunity for the interconnection of the world under a global digital ecosystem. However, mistrust between nations has led to the emergence of digital barriers, which imply their focus on controlling their digital sovereignty (…). These developments threaten current forms of interconnectivity, causing high-tech markets to fragment and retract, to varying degrees, upon national states”. (Brookings, 2022). Thus, the last sector of globalisation, which still showed significant dynamism, is also reversing under the impact of geopolitics. Globalisation, no doubt about it, seems to be experiencing sunset.

References

Brookings (2022). “The geopolitics of AI and the rise of digital sovereignty”, December 8.

Cheng, Ting Fang (2022). “TSMC founder Morris Chang says globalization is ‘almost dead’, Nikkei, December 7.

Doherty, J. and Yardeni, E. (2022). “Onshoring: Back to the USA”, Predicting the Markets, February 5.

Foroohar, Rana (2022). Homecoming. New York: Crown.

Ma, Cathy (2021). “83% of North American Manufacturers are Likely to Reshore Their Supply Chains”, Thomas, June 30.

McKinsey & Company (2020). “Could climate change become the weak link in your supply chain”, August 6.

McKinsey Global Institute (2016). “Digital Globalization: The New Era of Global Flows”, March.

Milanovic, Branko (2018). Global Inequality. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

OCDE (2010). “The Emerging Middle Class in Developing Countries”, Working Paper Number 285.

O’Neil, Shannon K. (2022). The Globalization Myth. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Prestowitz, Clyde (2022). “Is the U.S. Moving Out from Free Trade? Industrial Policy Comes Full Circle”, Clyde’s Newsletter, December 12.

Scholz, Olaf (2023). “The Global Zeitenwende”. Foreign Affairs, January/February.

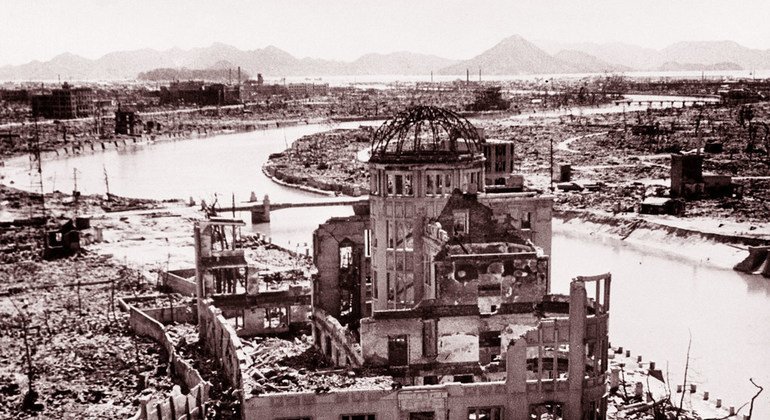

Feature Image Credit: worldcrunch.com (Globalization as Ideology is Dead and Buried).

Image Credit: Gulliver’s Travails (Paresh Nath, The Khaleej Times, UAE) www.uncommonthoughts.com