GDP data for China, the U.S., and the other G7 countries for the year 2023 has now been published. This makes possible an accurate assessment of China’s, the U.S., and major economies performance—both in terms of China’s domestic goals and international comparisons. There are two key reasons this is important.

- First for China’s domestic reasons: to achieve a balanced estimate of China’s socialist economic situation and therefore the tasks it faces.

- Second, because the U.S. has launched a quite extraordinary propaganda campaign, including numerous straightforward factual falsifications, to attempt to conceal the real international economic facts.

The factual situation is that China’s economy, as it heads into 2024, has far outgrown all other major comparable economies. This reality is in total contradiction to claims in the U.S. media. This in turn, therefore, demonstrates the extraordinary distortions and falsifications in the U.S. media about this situation. It confirms that, with a few honourable exceptions, Western economic journalism is primarily dominated by, in some cases quite extraordinary, “fake news” rather than any objective analysis. Both for understanding the economic situation, and the degree of distortion in the U.S. media, it is therefore necessary to establish the facts of current international developments

China’s growth targets

Starting with China’s strategic domestic criteria, it has set clear goals for its economic development over the next period which will complete its transition from a “developing” to a “high-income” economy by World Bank international standards. In precise numbers, in 2020’s discussion around the 14th Five Year plan, it was concluded that for China by 2035: “It is entirely possible to double the total or per capita income”. Such a result would mean China decisively overcoming the alleged “middle income trap” and, as the 20th Party Congress stated, China reaching the level of a “medium-developed country by 2035”.

In contrast, a recent series of Western reports, widely used in anti-China propaganda, claim that China’s economy will experience sharp slowdown and will fail to reach its targets.

Self-evidently which of these outcomes is achieved is of fundamental importance for China’s entire national rejuvenation and construction of socialism—as Xi Jinping stated, China’s: “path takes economic development as the central task, and brings along economic, political, cultural, social, ecological and other forms of progress.” But the outcome also affects the entire global economy—for example, a recent article by the chair of Rockefeller International, published in the Financial Times, made the claim that what was occurring was China’s “economy… losing share to its peers”. The Wall Street journal asserted: “China’s economy limps into 2024” whereas in contrast the U.S. was marked by a “resilient domestic economy.” The British Daily Telegraph proclaimed China has a “stagnant economy”. The Washington Postheadlined that: “Falling inflation, rising growth give U.S. the world’s best recovery” with the article claiming: “in the United States… the surprisingly strong economy is outperforming all of its major trading partners.” This is allegedly because: “Through the end of September, it was more than 7 percent larger than before the pandemic. That was more than twice Japan’s gain and far better than Germany’s anaemic 0.3 percent increase.” Numerous similar claims could be quoted from the U.S. media.

U.S. use of “fake news”

Reading U.S. media claims on these issues, and comparing them to the facts. it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that what is involved is deliberate “fake news” for propaganda purposes—as will be seen, the only alternative explanation is that it is disgracefully sloppy journalism that should not appear in supposedly “quality” media. For example, it is simply absurdly untrue, genuinely “fake news”, that the U.S. is “outperforming all of its major trading partners”, or that China has a “stagnant economy”. Anyone who bothers to consult the facts, an elementary requirement for a journalist, can easily find out that such claims are entirely false—as will be shown in detail below.

To first give an example regarding U.S. domestic reports, before dealing with international aspects, a distortion of U.S. economic growth in 2023 was so widely reported in the U.S. media that it is again hard to avoid the conclusion that this was a deliberate misrepresentation to present an exaggerated view of U.S. economic performance. Factually, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the U.S. official statistics agency for economic growth, reported that U.S. GDP in 2023 rose by 2.5%—for comparison China’s GDP increased by 5.2%. But a series of U.S. media outlets, starting with the Wall Street Journal, instead proclaimedthat the “U.S. economy grew 3.1% over the last year”.

This “fake news” on U.S. growth was created by statistical “cherry picking”. In this case comparing only the last quarter of 2023 with the last quarter of 2022, which was an increase of 3.1%, but not by taking GDP growth in the year as a whole “last year”. But U.S. growth in the earlier part of 2023 was far weaker than in the 4th quarter—year on year growth in the 1stquarter was only 1.7% and in the 2nd quarter only 2.4%. Taking into account this weak growth in the first part of the year, and stronger growth in the second, U.S. growth for the year as a whole was only 2.5%—not 3.1%. As it is perfectly easy to look up the actual annual figure, which was precisely published by the U.S. statistical authorities, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that this was a deliberate distortion in the U.S. media to falsely present a higher U.S. growth rate in 2023 than the reality.

It may be noted that even if U.S. GDP growth had been 3.1% then China’s was much higher at 5.2%. But the real data makes it transparently clear that China’s economy grew more than twice as fast as the U.S. in 2023—showing at a glance that claims that the U.S. is “outperforming all of its major trading partners”, or that China has a “stagnant economy” were entirely “fake news”.

Many more examples of U.S. media false claims could be given, but the best way to see the overall situation is to systematically present the overall facts of growth in the major economies.

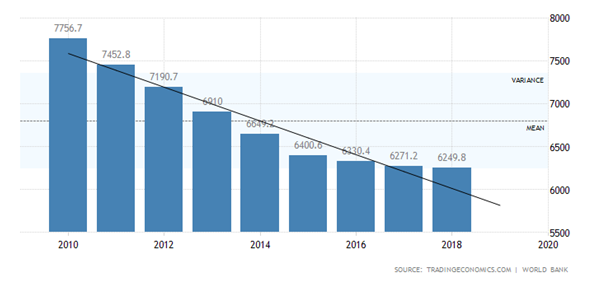

What China has to do to achieve its 2035 goals

Turning first to assessing China’s economic performance, compared to its own strategic goals of doubling GDP and per capita GDP between 2020 and 2035, it should be noted that in 2022 China’s population declined by 0.1% and this fall is expected to continue—the UN projects China’s population will decline by an average 0.1% a year between 2020 and 2035. Therefore, in economic growth terms, the goal of doubling GDP growth to 2035 is slightly more challenging than the per capita target and will be concentrated on here—if China’stotal GDP goal is achieved then the per capita GDP one will necessarily be exceeded.

To make an international comparison of China’s growth projections compared with the U.S., the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO), responsible for the official growth projections for the U.S. economy on which its government’s policies rely, estimates there will be 1.8% annual average U.S. GDP growth between 2023 and 2023—with this falling to 1.6% from 2034 onwards. This figure is slightly below the current U.S. 12-year long term annual average GDP growth of 2.3%—12 being the number of years from 2023 to 2035. To avoid any suggestion of bias against the U.S., and in favour of China, in international comparisons here the higher U.S. number of 2.3% will be used.

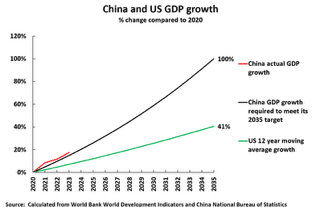

The results of such figures are that if China hits its growth target for 2035, and the U.S. continues to grow at 2.3%, then between 2020 and 2035 China’s economy will grow by 100% and the U.S. by 41%—see Figure 1. Therefore, from 2020 to 2035, China’s economy would grow slightly more than two and a half times as fast as the U.S.

The strategic consequences of China’s economic growth rate

The international implications of any such growth outcomes were succinctly summarised by Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator of the Financial Times. If China’s economy continues to grow substantially faster than Western ones, and it achieves the status of a “medium-developed country by 2035”, then, in addition to achieving high domestic living standards, China’s will become by far the world’s largest economy. As Wolf put it: “The implications can be seen in quite a simple way. According to the IMF, China’s gross domestic product per head (measured at purchasing power) was 28 per cent of U.S. levels in 2022. This is almost exactly half of Poland’s relative GDP per head… Now, suppose its [China’s] relative GDP per head doubled, to match Poland’s. Then its GDP would be more than double that of the U.S. and bigger than that of the U.S. and EU together.” By 2035 such a process would not be completed on the growth rates already given, and measuring by Wolf’s chosen measure of purchasing power parities (PPPs) China’s economy by 2035 would be 60% bigger than that of the U.S. But even that would make China by far the world’s largest economy.

Wolf equally accurately notes that the only way that such an outcome would be prevented from occurring is if China’s economy slows down to the growth rate of a Western economy such as the U.S. Clearly, if China’s economic growth slows to that of a Western economy, then, naturally, China will never catch up with the West—it will necessarily simply stay the same distance behind. Therefore. as Wolf accurately puts it the outcomes are:

What is the economic future of China? Will it become a high-income economy and so, inevitably, the largest in the world for an extended period, or will it be stuck in the ‘middle income’ trap, with growth comparable to that of the U.S.?

The progress in achieving China’s strategic economic goals

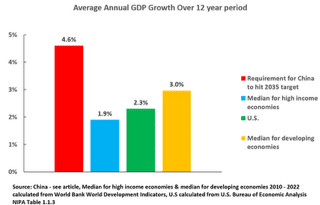

Turning to the precise figure required to achieve China’s 2035 target, China’s goal of doubling GDP required average annual growth of at least 4.7% a year between 2020 and 2035. So far China, as Figure 1 shows, is ahead of this goal—annual average growth in 2020-2022 was 5.7%, meaning that from 2023-2035 annual average 4.6% growth is now required.

China’ 5.2% GDP increase in 2023 therefore once again exceeded the required 4.6% growth rate to achieve its 2035 goal—as shown in Figure 1. From 2020 to 2023 the required total increase in China’s GDP to hit its 2035 target was 14.9%, whereas in fact its growth was 17.5%. This is in line with the 45-year record since 1978’s Reform and Opening Up, during which entire period the medium/long term targets set by China have always been exceeded.

Therefore. to summarise, there is no sign whatever in 2023, or indeed in the period since 2020, that China will fail to meet its target of doubling GDP between 2020 and 2035—China is ahead of this target. Such a 4.6% growth rate would easily ensure China becomes a high-income economy by World Bank criteria well before 2035—the present criteria for this being per capita income of $13,846.

It should be noted, as discussed in in detail below, that a clear international conclusion flows from this necessary 4.6% annual average growth rate for China to achieve its strategic goals. It means that China must continue to grow much faster than the Western economies throughout this period to 2035—that is in line with China’s current trend. However, if China were to slow down to the growth rate of a Western economy, then it will fail to achieve its strategic goals to 2035, may not succeed in becoming a high income economy, and will necessarily remain the same distance behind the West as now. The implications of this will be considered below.

Systematic comparisons not “cherry picking”

Having considered China’s performance in 2023 terms of achieving its own domestic strategic goals we will now turn to actual results and a comparison of China with other international economies. This immediately shows the factual absurdity, the pure “fake news” of claims such as that the U.S. has “the world’s best recovery“ and “the United States… is outperforming all of its major trading partners.” On the contrary China has continued to far outgrow the U.S. economy not only in 2023 but in the entire last period. China’s outperformance of the other major Western economies, the G7, is even greater that of the U.S.

Entirely misleading claims regarding such international comparisons, used for propaganda as opposed to serious analysis, are sometimes made because data is taken from extremely short periods of time which are taken out of context—unrepresentative statistical “cherry picking” or, as Lenin put it, a statistical “dirty business”. Such a method is always erroneous, but it is particularly so during periods which were affected by the impact of the Covid pandemic as these caused extremely violent short-term economic fluctuations related to lock downs and similar measures. China’s assertion of superior growth is based on its overall performance, not an absurd claim that it outperforms every other economy, on every single measure, in every single period! Therefore, in making international comparisons, the most suitable period to take is that for since the beginning of the pandemic up to the latest available GDP data. As comparison of China with the U.S. is the most commonly made one, and particularly concentrated on by the U.S. media campaign, this will be considered first.

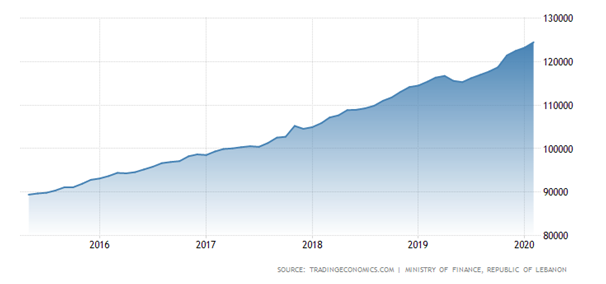

China’s and the U.S.’s growth in 2023

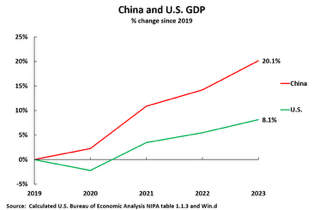

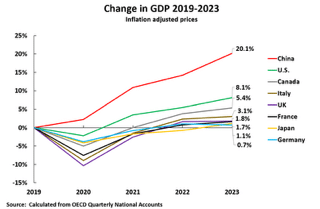

It was already noted that in 2023 China’s GDP grew by 5.2% and the U.S. by 2.5%—China’s economy growing more than twice as fast as the U.S. But it should also be observed that 2023 was an above trend growth year for the U.S.—U.S. annual average growth over a 12-year period is only 2.3% and over a 20-year period it is only 2.1%. Therefore, although in 2023 China’s economy grew more than twice as fast as the U.S., that figure is actually somewhat flattering for the U.S. Figure 2shows that in the overall period since the beginning of the pandemic China’s economy has grown by 20.1% and the U.S. by 8.1%—that is China’s total GDP growth since the beginning of the pandemic was two and half times greater than the U.S. China’s annual average growth rate was 4.7% compared to the US’s 2.0%.

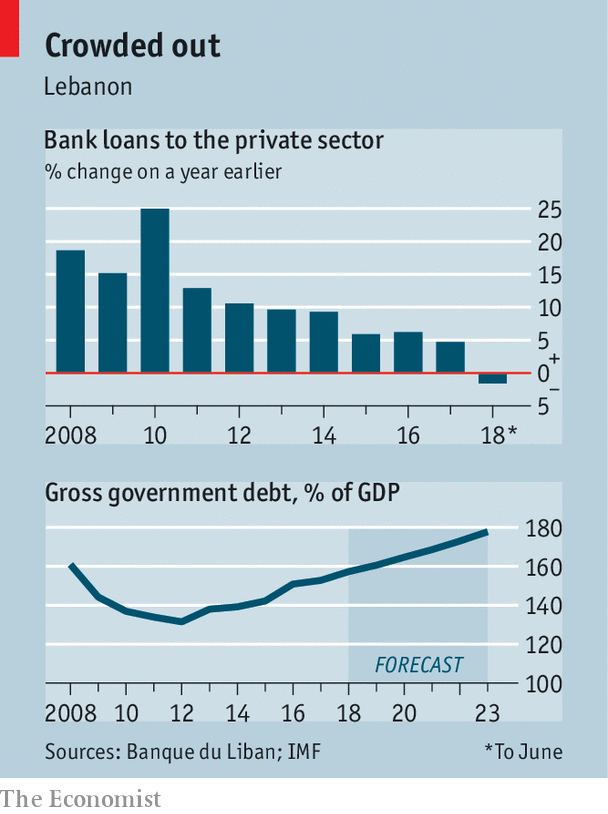

Economic performance of China and the three major global economic centres

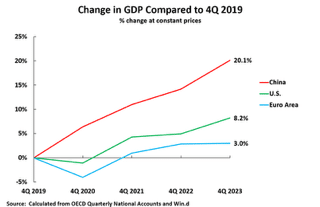

Turning to wider international comparisons than the U.S. such data immediately shows the extremely negative situation in most “Global North” economies and China’s great outperformance of them. To start by analysing this in the broadest terms, Figure 3 shows the developments in the world’s three largest economic centres—China, the U.S., and the Eurozone. These three together account for 57% of world GDP at current exchange rates and 46% in purchasing power parities (PPPs). No other economic centre comes close to matching their weight in the world economy.

Regarding the relative performance of these three major economic centres, at the time of writing data has not been published for the Euro Area for the whole year of 2023 —which would be the ideal comparison. However, it has been published for the the Euro area for the four quarters of 2023 individually and trends can be calculated on that basis. These show that In the four years to the 4th quarter of 2023, covering the period since the beginning of the pandemic, China’s economy has grown by 20.1%, the U.S. by 8.2%, and the Eurozone by 3.0%. China’s economy therefore grew by two and a half times as fast as the U.S. while the situation of the Eurozone could accurately be described as extremely negative with annual average GDP growth in the last four years of only 0.7%.

Such data again makes it immediately obvious that claims in the Western media that China faces economic crisis, and the Western economies are doing well is entirely absurd—pure fantasy propaganda disconnected from reality.

Relative performance of China and the G7

Turning to analysing individual countries, then comparing China to all G7 states, i.e. the major advanced economies, shows the situation equally clearly—see Figure 4. Data for China and all G7 economies has now been published for the whole of 2023. The huge outperformance by China of all the major advanced economies is again evident.

Over the four years since the beginning of the pandemic China’s economy grew by 20.1%, the U.S. by 8.1%, Canada by 5.4%, Italy by 3.1%, the UK by 1.8%, France by 1.7%, Japan by 1.1% and Germany by 0.7%.

In the same period China’s economy therefore grew two and a half times as fast as the U.S., almost four times as fast as Canada, almost seven times as fast as Italy, 11 times as fast as the UK, 12 times as fast as France, 18 times as fast as Japan and almost 29 times as fast as Germany.

In terms of annual average GDP growth during this period China’s was 4.7%, the U.S. 2.0%, Canada 1.3%, Italy 0.8%, the UK 0.4%, France 0.4%, Japan 0.3% and Germany 0.2%.

It may therefore be seen that China’s economy far outperformed the U.S., while the performance of all other major G7 economies may be quite reasonably described as extremely negative—all having annual average economic growth rates of around or even under 1%.

Comparison of China to developing economies

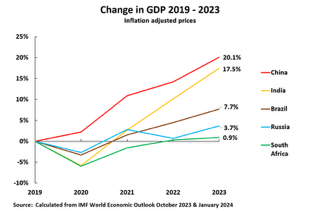

A comparison using the IMF’s January 2024 projections can also be made to the major developing economies—the BRICS. Figure 5 shows this, using the factual result for China and the IMF projections for the other countries. Over the period since the start of the pandemic, from 2019-2023, China’s GDP grew by 20.1%, India by 17.5%, Brazil by 7.7%, Russia by 3.7% and South Africa by 0.9%.

This data confirms that the major Global South economies are growing faster than most of the major Global North economies, which is part of the rise of the Global South and draws attention to the good performance of India. But China grew more than two and half times more than all the BRICS economies except India—China’s growth was 15% greater than India’s. It should be noted that India is at a far lower stage of development than the other BRICS economies—all the others fall in the World Bank classification of upper middle-income economies whereas India falls into the lower middle income group.

Comparison of China’s growth to Western economies

Finally, this outperformance by China casts light on what is necessary to achieve its own 2035 strategic targets. China’s 4.6% growth rate necessary to meet these goals means that it must continue to maintain a growth rate far higher than Western economies—Figure 6 shows this in overall terms in addition to individual comparisons given to major economies above. Whereas China must achieve an annual average 4.6% growth rate the median growth rate of high income “Western” economies is only 1.9%, the U.S. is 2.3%, and the median for developing economies is 3.0%.That is, to achieve its 2035 goals China must grow twice as fast as the long term trend of the U.S., almost two and a half times as fast as the median for high income economies, and more than 50% faster than the median for developing economies. As already seen, China is more than achieving this.

But such facts immediately show why it is an extremely misleading when proposals are made that China should move towards the macro-economic structure of a Western economy. If China adopts the structure of a Western economy then, of course, China will slow down to the same growth rate as Western economies—and therefore fail to achieve its 2035 economic goals. China will be precisely stuck in the negative outcome of the situation accurately diagnosed by Martin Wolf.

What is the economic future of China? Will it become a high-income economy and so, inevitably, the largest in the world for an extended period, or will it be stuck in the ‘middle income’ trap, with growth comparable to that of the U.S.?

Conclusion

In conclusion, it addition to objectively analysing 2023’s economic results, it is also necessary in the light of this factual situation to make a remark regarding Western, in particular U.S. “journalism”.

None of the data given above is secret, all is available from public readily accessible sources. In many cases it does not even require any calculations and simply published data can be used. But the U.S. media and journalists report information that is systematically misleading and in many cases simply untrue. While it lagged China in creating economic growth the U.S. was certainly the world leader in creating “fake economic news”! What was the reason, what attitude should be taken to it?

First, to avoid accusations of distortion, it should be stated that there were a small handful of Western journalists who refused to go along with this type of distortion and fake news. For example Chris Giles, the Financial Times economics commentator, in December, sharply attacked “an absurd way to compare economies… among people who should know better.” Giles did not do this because of support for China but because, quite rightly, he warned that spreading false or distorted information led to serious errors by countries doing so: “Coming from the UK, which lost its top economic dog status in the late 19th century but still has some delusions of grandeur, I can understand American denialism… But ultimately, bad comparisons foster bad decisions.” But the overwhelming majority of U.S. and Western journalists continued to spread fake news. Why?

First, the fact that identical distortions and false information appeared absolutely simultaneously across a very wide range of media makes it clear that undoubtedly U.S. intelligence services were involved in creating it—i.e. part of the misrepresentation and distortions were entirely deliberate and conscious, aimed at disguising the real situation.

Second, another part was merely sloppy journalism—that is journalists who could not be bothered to check facts.

Third, supporting both of these factors was “white Western arrogance”—an arrogant assumption, rooted in centuries of European and European descended countries dominating the world, that the West must be right. Therefore, such arrogance made it impossible to acknowledge or report the clear facts that China’s economy is far outperforming the West.

But whether it was conscious distortion, sloppy journalism, or conscious or unconscious arrogance, in all these cases no respect should be given to the Western “quality” media. It is not trying to find out the truth, which is the job of journalism, it is simply spreading false propaganda.

It remains a truth that if a theory and the real world don’t coincide there are only two courses that can be taken. The first, that of a sane person, is to abandon the theory. The second, that of a dangerous one, is to abandon the real world—precisely the danger that Chris Giles pointed to. What has been appearing in the Western media about international economic comparisons regarding China is precisely abandonment of the real world in favour of systematic fake news.

This article was published earlier in mronline.org and is republished under Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International License

Feature Image Credit: China will continue to lead global growth in 2024 – globaltimes.cn