Background

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Philippines, a twice-colonized archipelago that achieved its complete independence in 1946, is a member of the ASEAN and an essential player in the geopolitics of the Southeast Asia region. Its status is owed mainly to its rapidly growing economy, of which the services industry is the most significant contributor, comprising 61% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bajpai, 2022). Services refer to various products – for example, business outsourcing, tourism, and the export of skilled workers, healthcare workers, and labourers in other industries. In recent years, a growing demand for qualified professionals has grown as the economy has grown, thus necessitating more robust educational systems (Bajpai, 2022). Although the Philippines has a high literacy rate, hovering at around 97%, the efficacy of its educational system is often called into question (“Literacy Rate and Educational Attainment”, 2020). Administration oversight, infrastructural deficiencies, and pervasive corruption in the government that seeps into the entities responsible for educational reform are significant issues that legitimize these doubts (Palatino, 2023). However, reforming the current flaws in the system requires an understanding of the basic underlying structure of the country’s educational system as it is today. This fundamental understanding can help clarify specific political trends in the status quo and highlight the importance of proper historical education in developing a nation. Despite its ubiquity in nearly every curriculum, the study of history as a crucial part of the education system is often not prioritized, leading to an underdeveloped understanding of the society’s culture and previous struggles with colonial exploitation. Though it is present in the Philippines’ education today, it continues to change because of its historically dynamic demographic and political atmosphere.

The Philippines, a twice-colonized archipelago that achieved its complete independence in 1946, is a member of the ASEAN and an essential player in the geopolitics of the Southeast Asia region. Its status is owed mainly to its rapidly growing economy, of which the services industry is the most significant contributor, comprising 61% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bajpai, 2022). Services refer to various products – for example, business outsourcing, tourism, and the export of skilled workers, healthcare workers, and labourers in other industries. In recent years, a growing demand for qualified professionals has grown as the economy has grown, thus necessitating more robust educational systems (Bajpai, 2022). Although the Philippines has a high literacy rate, hovering at around 97%, the efficacy of its educational system is often called into question (“Literacy Rate and Educational Attainment”, 2020). Administration oversight, infrastructural deficiencies, and pervasive corruption in the government that seeps into the entities responsible for educational reform are significant issues that legitimize these doubts (Palatino, 2023). However, reforming the current flaws in the system requires an understanding of the basic underlying structure of the country’s educational system as it is today. This fundamental understanding can help clarify specific political trends in the status quo and highlight the importance of proper historical education in developing a nation. Despite its ubiquity in nearly every curriculum, the study of history as a crucial part of the education system is often not prioritized, leading to an underdeveloped understanding of the society’s culture and previous struggles with colonial exploitation. Though it is present in the Philippines’ education today, it continues to change because of its historically dynamic demographic and political atmosphere.

Origins of the Education System

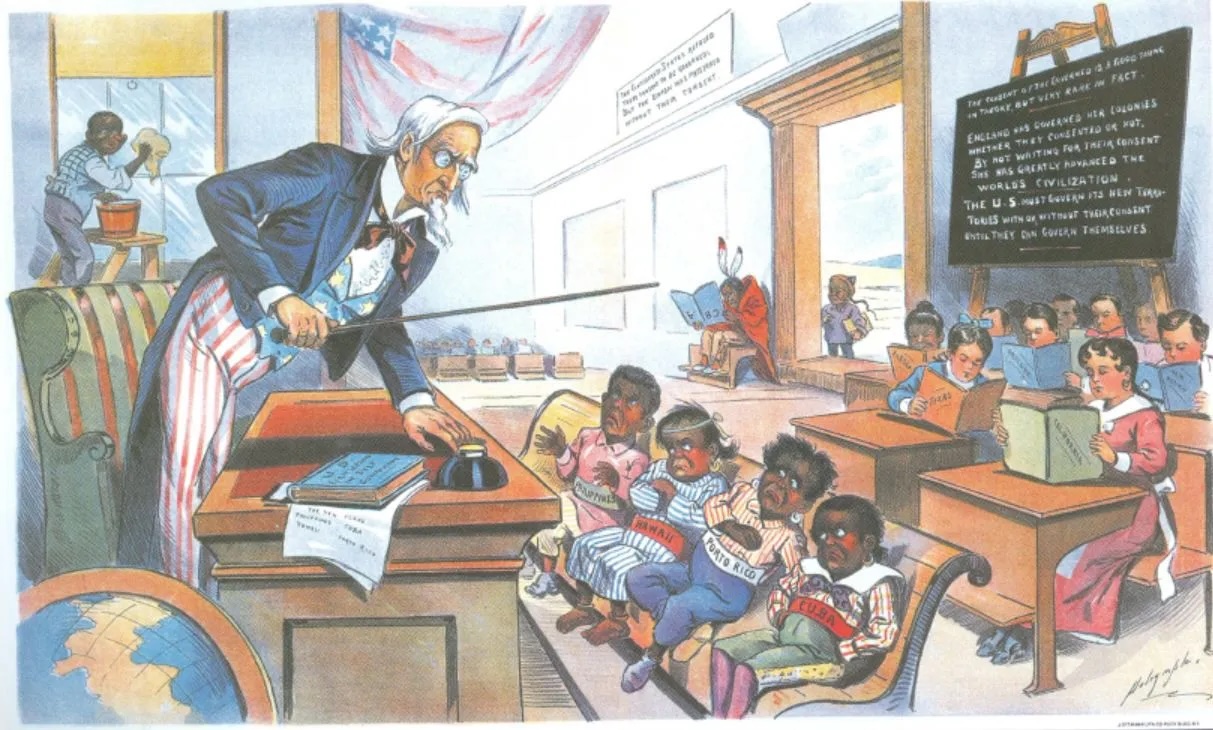

To begin with, the educational system, and especially the modes of linguistic and history education in the country, have been heavily influenced by the major powers that occupied it – namely, the Spanish Empire and the United States. The impact of these periods of colonization can be seen most significantly in the historical education and consciousness of the general population, as well as the propagation of the English language. The Philippines possesses a great deal of linguistic diversity, especially among indigenous groups – an estimated 170 distinct languages in the country today (Postan, 2020). However, even in pre-colonial times – typically considered by historians to be the years before 1521 – the most common language in the country was Old Tagalog, and other indigenous languages are still spoken today (Stevens, 1999). Records suggest that the Spanish did not forcefully erase indigenous languages spoken in the country. However, they did conduct business and educational institutions in Spanish, leading to the language being used almost exclusively amongst the upper classes – the colonizers, business people in the country, and other influential figures in the empire. Though there were attempts to conduct education in Castilian Spanish, priests and friars responsible for teaching the locals preferred to do so in local languages as it was a more effective form of proselytization. This cemented the reputation of Spanish as a language for the elite, as the language was almost exclusively limited to those chosen to attend prestigious institutions or government missions that operated entirely in Spanish (Gonzales, 2017). In terms of popularising education to expose a broader audience to Christianity, the Spanish also established a compulsory elementary education system. However, restrictions existed based on social class and gender (Musa & Ziatdinov, 2012). Because of this, although the influence of Spanish on local languages can be seen through the borrowing of certain words, indigenous and regional languages were not supplanted to a large extent, though their scripts were Latinised in some instances to make matters more convenient for the Spanish (Gonzales, 2017). However, the introduction of Catholicism to a large segment of the population and a more organized educational system are aspects of Spanish rule that remain in Philippine society today, as do the negative ramifications of the social stratification that was a significant element of its occupation (Herrera, 2015).

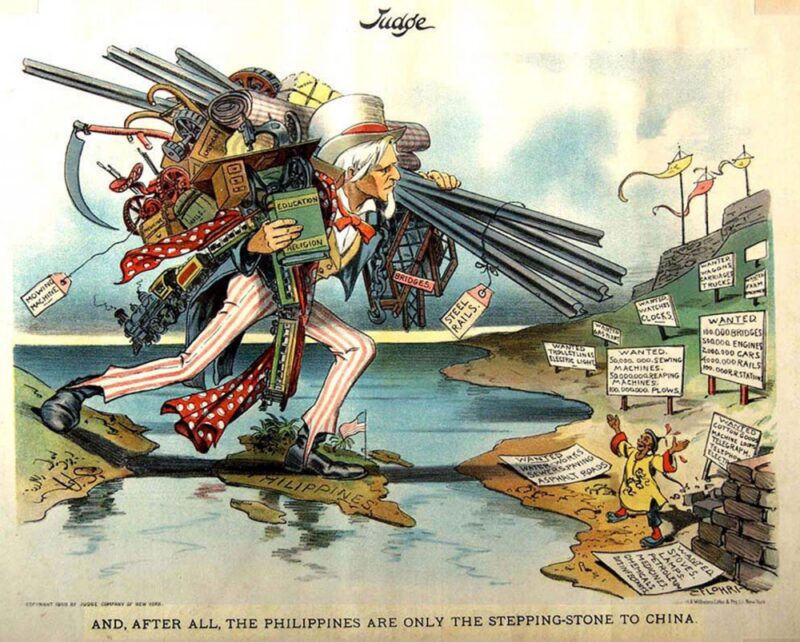

Uncle Sam, loaded with implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to get across the Pacific to China (represented by a small man with open arms), who excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. With the expansionist policy gaining greater traction, the possibility for more imperialistic missions (including to conflict-ridden China) seemed strong. The cartoon might be arguing that such endeavours are worthwhile, bringing education, technological, and other civilizing tools to a desperate people. On the other hand, it could be read as sarcastically commenting on America’s new propensity to “step” on others. “AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA,” in Judge Magazine, 1900 or 1902. Wikimedia.

Uncle Sam, loaded with implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to get across the Pacific to China (represented by a small man with open arms), who excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. With the expansionist policy gaining greater traction, the possibility for more imperialistic missions (including to conflict-ridden China) seemed strong. The cartoon might be arguing that such endeavours are worthwhile, bringing education, technological, and other civilizing tools to a desperate people. On the other hand, it could be read as sarcastically commenting on America’s new propensity to “step” on others. “AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA,” in Judge Magazine, 1900 or 1902. Wikimedia.

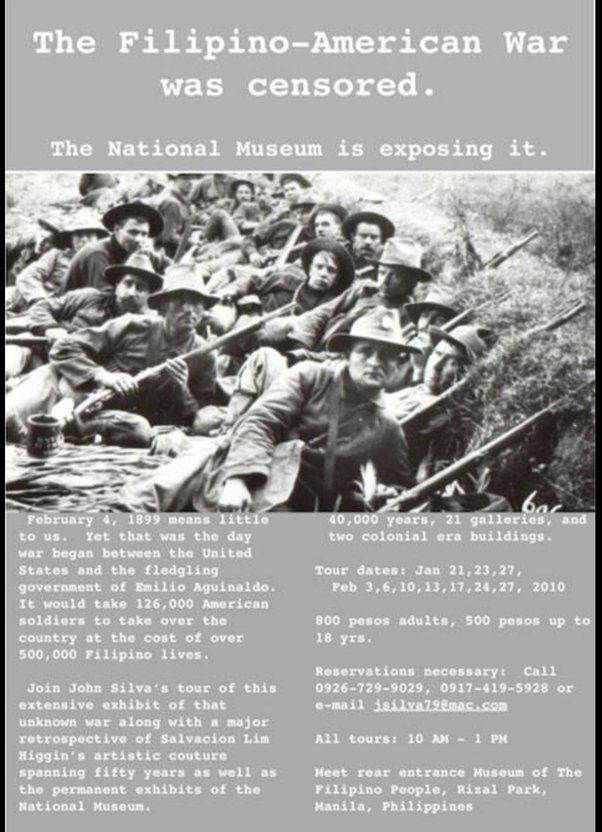

In contrast, the American occupation following Spain’s defeat in the Spanish-American War in 1898 significantly changed the country’s linguistic patterns and revolutionized the education system. Upon arriving in the country, the Americans decided to create a public school system in the country, where every student could study for free. However, the medium of instruction was in English, given that they brought teachers from the United States (Casambre, 1982). This differed from the Spanish system in that social class and gender did not influence students’ access to education to the same extent. Furthermore, the Americans brought their own material to the country due to a lack of school textbooks. As the number of schools in the country and the pedagogical influence of American teachers increased, the perception of the Americans’ role as colonizers ultimately changed. Education became a tool to exert cultural influence, leading to the propagation of American ideals like capitalism, in addition to subverting separatist tendencies that were cropping up in the country as one colonizer was replaced by another. It also led to the suppression of knowledge concerning the US’ exploitation of the nation. Ultimately, the colonizers’ influence on the linguistic and educational landscape of the nation manifests itself in the general population’s understanding of their country’s history.

The Current History Curriculum

The social studies curriculum in the Philippines, called Araling Panlipunan (AP), is an interdisciplinary course that combines topics of economics and governance with history, primarily post-colonial history (“K to 12 Gabay Pangkurikulum”, 2016). The topic of World War II takes up nearly 50% of the course, while other aspects of indigenous and pre-colonial history are included to a limited extent (Candelaria, 2021). This act of prioritization is a colonial holdover. Although the Philippines indubitably played a crucial role in the Pacific Theatre during WW II, its massive presence in the AP course signals the nation’s continued alliance with the US and reinforces a mentality amongst the general public that favours it. This bias occurs as a singular American perspective is promoted by the course, wherein the actions of other countries against the Philippines are highlighted. At the same time, the exploitation of the Philippines by the Spanish and Americans is not as widely discussed. For example, although the atrocities committed by the Japanese during World War II are taught extensively as part of the curriculum, the American actions during the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), during which the Americans burned and pillaged entire villages, are not emphasized (Clem, 2016). Furthermore, it leads to the sidelining of historical events that have created the political situation in the country today, such as the issue of the current president being related to the former dictator, Ferdinand Marcos.

As the course is conducted chronologically, discussions of topics such as the Marcos Regime are left up to teachers’ discretion due to the subject’s controversial nature, given that the dictator’s son is the current president (Santos, 2022). This means that as much or as little time can be spent on it is as decided. Because of the American influence, even citizens who are taught about the atrocities that occurred during the dictatorship are not informed of the support provided to the Marcos dictatorship by the US government. During his presidency, which lasted from 1965 to 1986, the Philippines received significant economic aid from the US government in exchange for the continuation of its military presence in the country, which proved helpful to the US during the Vietnam War as it was able to utilize its bases in Subic Bay and Clark air base(Hawes, 1986). As a result of the necessity of these bases, a 1979 amendment to the 1947 Military Bases Agreement was signed, which increased the US’ fiscal contributions to security assistance. To further support this military objective, the Carter and Reagan administrations showed their diplomatic support to Marcos by visiting the Philippines and inviting him to Washington.

Additionally, when Marcos was ousted from power in 1986 by the People Power Revolution, he spent his exile in ‘Hawaii’, in the US (Southerl, 1986). Therefore, while the US is credited for introducing democratic principles to the country through its program for expanding education while occupying the archipelago, it also played a significant role in supporting a despotic government that is not as widely acknowledged. Because of this, the Filipino perception of and relationship with the US has been heavily influenced by a lack of awareness amongst the general public about its involvement in a massively corrupt administration.

Significant Developments

Despite the importance of a robust historical education in improving the public’s awareness of their own culture and geopolitical relationships, history as a subject has been transformed into a political tool in the Philippines, twisted when it can be useful and neglected when it does not support an agenda. Various bills passed in the House of Representatives (the lower house of parliament in the Philippines, below the Senate), as well as decisions taken by the Department of Education, have diminished the significance of history in the overall school curriculum and reinforced an American perspective in the historical content that continues to be taught. Department of Education Order 20, signed in 2014, removed Philippines History as a separate subject in high school (Ignacio, 2019). The argument for this decision was that Philippines History would be integrated within the broader AP social studies curriculum under different units, such as the Southeast Asian political landscape. However, educators opposing the abolition of Philippine History as a separate subject state that due to fewer contact hours being allocated for AP in total compared to English, maths, and science, it is unlikely that Philippine history can be discussed in adequate depth, considering the other social science topics mandated by the AP curriculum. In addition, House Bill 9850, which was passed in 2021, requires that no less than 50% of the subject of Philippine history centres around World War II (Candelaria, 2021). The bill’s primary concerns mention that it prioritizes the war over other formative conflicts in the nation’s history, such as the Philippine Revolution against Spain or the Philippine-American War. Furthermore, it requires modifying or reducing discussions surrounding other vital events in the Philippines, such as agrarian reforms and more recent developments like the conflict in Mindanao.

Both of these policies face significant opposition. For example, a Change.org petition demanding the return of the subject of Philippine history in high schools has garnered tens of thousands of signatures. At the same time, numerous historical experts and teachers have spoken against HB 9850 (Ignacio, 2018). Despite this resistance from academics and teaching professionals, it is unlikely that history will be prioritized unless the general public also learns to inform itself. Around 73% of the total population (approximately 85.16 million people) have access to the internet, of which over 90% are on social media (Kemp, 2023). Because of the large working population in the country, social media companies like Facebook have set up offices there. Programs that offered data-free usage in 2013 have made the Philippines a huge market for Facebook, and many Filipinos trust the news they find on the website more than some mainstream media sources (Quitzon, 2021). Even though internet access is relatively widespread, signifying that information is readily available to the average Filipino, social media, especially Facebook, often functions as a fertile breeding ground for misinformation.

Repercussions of the History Curriculum

In recent years, misinformation has become an important political tool to propagate ignorance and manipulate historical and current events to promote specific agendas. The most relevant example was the mass historical revisionism campaign leading to the 2022 general elections (Quitzon, 2021). Given that Bongbong Marcos, Ferdinand Marcos’ son, was running for president alongside vice presidential candidate Sara Duterte (former president Rodrigo Duterte’s daughter), the campaign focused on changing the public perception of both families and their period of rule. Preceding the elections, social media trolls and supporters of the campaign spread videos, doctored images, and fake news that minimized the atrocities and scale of theft that occurred throughout the Marcos regime and the Duterte administration, instead highlighting and exaggerating the perceived benefits they brought to the country. The prioritization of these political agendas is reflected in the history curriculum, as it does not sufficiently cover critical areas of Philippine history that have directly led to the political situation of today and the pre-colonial era that is an inseparable part of Filipino culture.

Recommended Policy Measures

However, another by-product of this absence of consciousness is that the general public is desensitized to poor governance and neocolonialism as their education systems and news sources constantly feed them biased and inaccurate information about the history of their own country and its relationship to others. When dictators are portrayed as good rulers and previous colonizers are portrayed as historical allies, it results in a population that unknowingly votes against its interests as they are unaware of the past events that have shaped the current political atmosphere and the various deficiencies in the system. Considering that these political campaigns rely on the general public not having a solid understanding of historical events, especially those about the martial law era, it is unlikely that politicians will take meaningful steps to improve historical education in the country since they benefit from citizens lacking awareness. As such, the onus must, unfortunately, be placed on the general public to educate themselves on good citizenship and exercise their right to vote at the grassroots level responsibly so that future local politicians and members of parliament may at least be able to encourage the study of history in the government. Additionally, teaching students how to use the internet to conduct reliable research is imperative to reduce misinformation so they can counter the misinformation they find online.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Philippine education system has been shaped by the periods of colonization the country has experienced. This has led to a history curriculum favouring the American perspective and thus disadvantages crucial elements of local history. The consequences of the lack of awareness this has caused in the general public are manifold: it has made them more susceptible to misinformation and historical revisionism. It has worked to the advantage of politicians who take advantage of it. Nevertheless, the Philippines can still reverse this trend by utilizing its high literacy rates and social media presence to promote reliable historical education. They can also push for better historical education policies through petitions and appeals to local government agencies and Senate committees related to education – such as the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the Committee on Basic Education and Culture, and the Committee on Education, Arts and Culture – amongst others (Ignacio, 2018). Overall, there are many deficiencies in the current history education system in the Philippines, but they still coexist with the potential for change. Citizens have the power to advocate and must continue using it to usher forth a more well-informed society and nation.

References

Bajpai, Prableen. “Emerging Markets: Analyzing the Philippines’s GDP.” Investopedia, 12 July 2023, www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/091815/emerging-markets-analyzing-philippines-gdp.asp#:~:text=The%20country.

Casambre, Napoleon. The Impact of American Education in the Philippines. Educational Perspectives, scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/f3bbc11f-f582-4b73-8b84-76cfd27a6f77/content#:~:text=Under%20the%20Americans%2C%20English%20was.

Clem, Andrew. “The Filipino Genocide.” Series II, vol. 21, 2016, p. 6, scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1138&context=historical-perspectives.

Constantino, Renato. “The Miseducation of the Filipino.” Journal of Contemporary Asia, vol. 1, no. 1, 1970, eaop.ucsd.edu/198/group-identity/THE%20MISEDUCATION%20OF%20THE%20FILIPINO.pdf.

Department of Education. K To12 Gabay Pangkurikulum. 2016, www.deped.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/AP-CG.pdf.

“Education Mass Media | Philippine Statistics Authority | Republic of the Philippines.” Psa.gov.ph, 28 Dec. 2019, psa.gov.ph/statistics/education-mass-media.

Gonzales, Wilkinson Daniel Wong. “Language Contact in the Philippines.” Language Ecology, vol. 1, no. 2, Dec. 2017, pp. 185–212, https://doi.org/10.1075/le.1.2.04gon.

Hawes, Gary. “United States Support for the Marcos Administration and the Pressures That Made for Change.” Contemporary Southeast Asia, vol. 8, no. 1, 1986, pp. 18–36, www.jstor.org/stable/25797880.

Herrera, Dana. “The Philippines: An Overview of the Colonial Era.” Association for Asian Studies, vol. 20, no. 1, 2015, www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/the-philippines-an-overview-of-the-colonial-era/.

Ignacio, Jamaico D. “[OPINION] The Slow Death of Philippine History in High School.” RAPPLER, 26 Oct. 2019, www.rappler.com/voices/ispeak/243058-opinion-slow-death-philippine-history-high-school/.

—. “We Seek the Return of ‘Philippine History’ in Junior High School and Senior High School.” Change.org, 19 July 2018, www.change.org/p/we-seek-the-return-of-philippine-history-in-junior-high-school-and-senior-high-school.

John Lee Candelaria. “[OPINION] The Dangers of a World War II-Centered Philippine History Subject.” RAPPLER, 20 Sept. 2021, www.rappler.com/voices/imho/opinion-dangers-world-war-2-centered-philippine-history-subject/.

Kemp, Simon. “Digital 2023: The Philippines.” DataReportal – Global Digital Insights, 9 Feb. 2023, datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-philippines#:~:text=Internet%20use%20in%20the%20Philippines.

Musa, Sajid, and Rushan Ziatdinov. “Features and Historical Aspects of the Philippines Educational System.” European Journal of Contemporary Education, vol. 2, no. 2, Dec. 2012, pp. 155–76, https://doi.org/10.13187/ejced.2012.2.155.

Quitzon, Japhet. “Social Media Misinformation and the 2022 Philippine Elections.” Center for Strategic & International Studies, 22 Nov. 2021, www.csis.org/blogs/new-perspectives-asia/social-media-misinformation-and-2022-philippine-elections.

Santos, Franz Jan. “How Philippine Education Contributed to the Return of the Marcoses.” Thediplomat.com, 23 May 2022, thediplomat.com/2022/05/how-philippine-education-contributed-to-the-return-of-the-marcoses/.

Southerl, Daniel. “A Fatigued Marcos Arrives in Hawaii.” Washington Post, 27 Feb. 1986, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/02/27/a-fatigued-marcos-arrives-in-hawaii/af0d6170-6f42-41cc-aee8-782d4c9626b9/.

Stevens, J. Nicole. “The History of the Filipino Languages.” Linguistics.byu.edu, 30 June 1999, linguistics.byu.edu/classes/Ling450ch/reports/filipino.html.

Stout, Aaron P. The Purpose and Practice of History Education: Can a Humanist Approach to Teaching History Facilitate Citizenship Education? 2019, core.ac.uk/download/pdf/275887751.pdf.

Feature Image Credit: actforum-online.medium.com Filipino Education and the Legacies of American Colonial Rule – Picture from ‘Puck’ Magazine