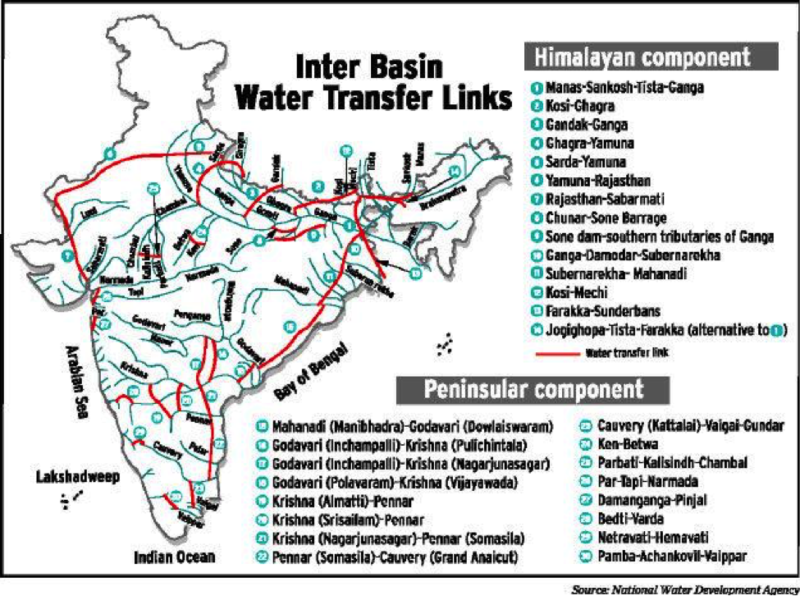

In October, India’s ambitious scheme to build a 230-kilometre canal between the Ken and Betwa rivers was finally approved. It’s the first of many projects planned for implementation under the National River Linking Project (NRLP), which aims to connect 37 Himalayan and peninsular rivers across the country via some 3,000 reservoirs and 15,000 kilometres of dams and canals. The government has touted the NRLP, which was first mooted more than four decades ago, as the solution to drought-proofing the country. But new research suggests the US$168 billion project could actually make the drought worse.

– From a study by the ‘Geographical‘ – Dec 2023.

I keep hearing that Modiji is going to unveil the often-spoken and then shelved Rivers Link Up Scheme as his grand vision to enrich the farmers and unite India. In a country where almost two-thirds of the agricultural acreage is rainfed, water is wealth. Telangana has shown the way. Once India’s driest region has in just eight years been transformed into another granary of India. Three years ago, he had promised to double farmers’ incomes by 2022, and he has clearly failed. He now needs a big stunt. With elections due in 2024, he doesn’t even have to show any delivery. A promise will do for now.

This is also a Sangh Parivar favourite, and I am quite sure the nation will once again set out to undertake history’s greatest civil engineering project by seeking to link all our major rivers. It will irretrievably change India. If it works, it will bring water to almost every parched inch of land and just about every parched throat in the land.

On the other hand, if it doesn’t work, Indian civilization as it exists even now might then be headed the way of the Indus Valley or Mesopotamian civilizations destroyed by a vengeful nature, for interfering with nature is also a two-edged sword. If the Aswan High Dam turned the ravaging Nile into a saviour, the constant diversion of the rivers feeding Lake Baikal have turned it into a fast-receding and highly polluted inland sea, ranking it as one of the world’s greatest ecological disasters. Even in the USA, though the dams across the mighty Colorado have turned it into a ditch when it enters Mexico, California is still starved for water.

I am not competent to comment on these matters, and I will leave this debate for the technically competent and our perennial ecological Pooh-Bahs. But the lack of this very debate is cause for concern. It is true that the idea of linking up our rivers has been afloat for a long time. Sir Arthur Cotton was the first to propose it in the 1800’s. The late KL Rao, considered by many to be an outstanding irrigation engineer and a former Union Minister for Irrigation, revived this proposal in the late 60’s by suggesting the linking of the Ganges and Cauvery rivers. It was followed in 1977 by the more elaborate and gargantuan concept of garland canals linking the major rivers, thought up by a former airline pilot, Captain Dinshaw Dastur. Morarji Desai was an enthusiastic supporter of this plan.

The return of Indira Gandhi in 1980 sent the idea back into dormancy, where it lay all these years, till President APJ Abdul Kalam revived it on the eve of the Independence Day address to the nation in 2002. It is well known that Presidents of India only read out what the Prime Ministers give them, and hence, the ownership title of Captain Dastur’s original idea clearly was vested with Atal Behari Vajpayee.

India’s acute water problem is widely known. Over sixty per cent of our cropped areas are still rain-fed, much too abjectly dependent on the vagaries of the monsoon. The high incidence of poverty in certain regions largely coincides with the source of irrigation, clearly suggesting that water for irrigation is integral to the elimination of poverty. In 1950-51, when Jawaharlal Nehru embarked on the great expansion of irrigation by building the “temples of modern India” by laying great dams across our rivers at places like Bhakra Nangal, Damodar Valley and Nagarjunasagar, only 17.4% or 21 million hectares of the cropped area of 133 million hectares was irrigated. That figure rose to almost 35% by the late 80s, and much of this was a consequence of the huge investment by the government in irrigation, amounting to almost Rs. 50,000 crores.

Ironically enough, this also coincided with the period when water and land revenue rates began to steeply decline to reach today’s zero level. Like in the case of power, it seems that once the activity ceased to be profitable to the State, investment too tapered off.

The scheme is humongous. It will link the Brahmaputra and Ganges with the Mahanadi, Godavari and Krishna, which in turn will connect to the Pennar and Cauvery. On the other side of the country, it will connect the Ganges, Yamuna, with the Narmada, traversing in part the supposed route of the mythical Saraswathi. This last link has many political and mystical benefits, too.

There are many smaller links as well, such as joining the Ken and Betwa rivers in MP, the Kosi with the Gandak in UP, and the Parbati, Kalisindh and Chambal rivers in Rajasthan. The project, when completed, will consist of 30 links, with 36 dams and 10,800 km of canals diverting 174,000 million cubic meters of water. Just look at the bucks that will go into this big bang. It was estimated to cost Rs. 560,000 crores in 2002 and entail the spending of almost 2% of our GNP for the next ten years. Now, it will cost twice or more than that, but our GDP is now three times more, and it might be more affordable and, hence, more tempting to attempt.

The order to get going with the project was the output of a Supreme Court bench made up of then Chief Justice BN Kirpal and Justices KG Balakrishnan and Arjit Pasayat, which was hearing a PIL filed by the Dravida Peravai, an obscure Tamil activist group. The learned Supreme Court sought the assistance of a Senior Advocate, Mr Ranjit Kumar, and acknowledging his advice, recorded: “The learned Amicus Curiae has drawn our attention to Entry 56 List of the 7th Schedule to the Constitution of India and contends that the interlinking of the inter-State rivers can be done by the Parliament and he further contends that even some of the States are now concerned with the phenomena of drought in one part of the country, while there is flood in other parts and disputes arising amongst the egalitarian States relating to sharing of water. He submits that not only these disputes would come to an end but also the pollution levels in the rivers will be drastically decreased, once there is sufficient water in different rivers because of their inter-linking.”

The only problem with this formulation is that neither the learned Amicus Curiae nor the learned Supreme Court are quite so learned as to come to such sweeping conclusions.

Feature Image Credit: geographical.co.uk

Opinions expressed are that of the author and do not reflect TPF’s position on the issue.