His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and his followers, were welcomed by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru with open arms whose government helped them settle in India as they fled Tibet, following the Chinese invasion

Introduction

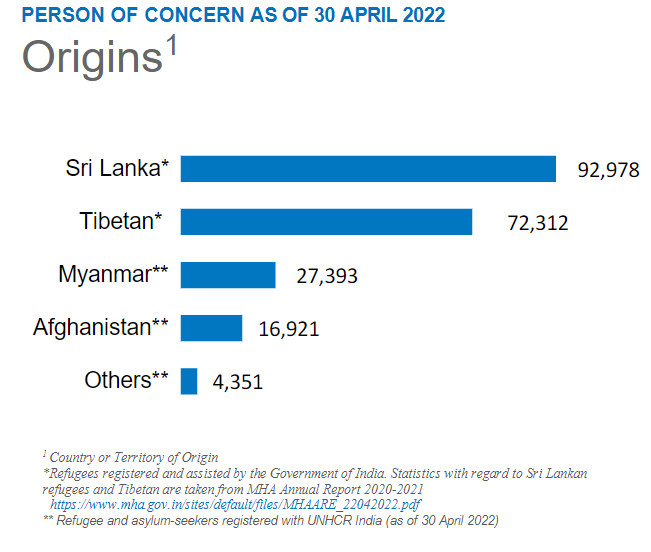

India is the largest democracy in the world, with a multi-party system, and a diverse set of cultures. It has a long tradition of hosting a large number of refugees. India has been particularly supportive of Tibetan refugees, right from the start of the Nehruvian era in the early 1950s. The number of Tibetan refugees living in India is estimated at well over 150,000 at any given time. However, a recent survey conducted by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in India, in association with the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), showed that only 72,312 Tibetans remain in the country.

In India, Tibetans are considered to be one of the most privileged refugees unlike other refugees in the country. His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and his followers, were welcomed by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru with open arms whose government helped them settle in India as they fled Tibet, following the Chinese invasion. That period saw a large influx of Tibetans towards India as they sought asylum. The Tibetan refugees have been allotted settlements where they continue to live under the management of the MHA and the Tibetan government-in-exile, or the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA). These facilities have contributed to a sense of community-living and have enabled them to keep their culture alive till today. Tibetan refugees in India have enjoyed freedom, which was impossible in their own land under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule. However, after residing in India for almost seven decades now, recent data estimates a large decline in the number of Tibetan refugees. Therefore, this study examines the theoretical concerns and empirical findings of refugee problems in general as well as distinctive features of the Tibetan refugee experience in India.

The status of Tibetans in India is determined under the Passports Act 1967, Foreigner’s Act of 1946, and the Registration of Foreigners Act of 1939 which refer to Tibetans as simply “foreigners”. These provisions cover everyone apart from Indian citizens thus, restricting refugees’ mobility, property, and employment rights. Recognizing this, the Government of India sanctioned the Tibetan refugees with the 2014 Tibetan Rehabilitation Policy (TRP) which caters to the issues faced by them and promises a better life for Tibetans in India. An array of provisions under this policy include land leases, employment, trade opportunities such as setting up markets for handicrafts and handlooms, housing, etc. to all Tibetans in possession of the RC (Registration Certificate). Further, certain policies applicable to Indian citizens are extended to Tibetan refugees as well. For instance, the Constitution of India grants the right to equality (Article 14) and the right to life and liberty (Article 21), and India is obliged to provide asylum as outlined in Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Despite these facilities and the cordial relationship that has been built over 70 years between the Tibetans and Indians, the question raised by many, including Indian authorities is – why is the number of Tibetans migrating out of India increasing?

With increased awareness about Tibetan refugees and their problems, many countries have opened their borders to Tibetans by introducing numerous favourable policies

The various push and pull factors- motivation for migration

The Tibetan Exit continues to grow with about 3000 refugees migrating out of India every year. The support and admiration of His Holiness the Dalai Lama gained worldwide has been partly due to the exhibition of the rich culture and traditions of Buddhism. With India being the birthplace of the religion, Tibetans in India caught the limelight in the global arena, leading many researchers to study their migration patterns to India. Attention is now being placed on Tibetans exiting India despite years of strong cultural and social bonding. General migratory trends of humans can be analyzed using eminent scholar Everett Lee’s comprehensive theory of migration of 1966. The term ‘migration’ is defined broadly as a permanent or semi-permanent change of residence. Many factors tend to hold people within the area or attract people towards it, and there are others that repel them from staying. This theory could also be applied to the Tibetan migratory trends by looking at the “Push and Pull” factors proposed by Lee. The ‘push theory’ here encompasses the aspects that encourage the Tibetans to emigrate outside India, and the pull theory is associated with the country of destination that attracts the Tibetans to emigrate. Ernest George Ravenstein, in his “Laws of Migration”, argues that ‘migrants generally proceed long distances by preference to one of the great centers of commerce and industry and that ‘the diversity of people defines the volume of migration’. Ravenstein’s laws provide a theoretical framework for this study, as Tibetans tend to migrate out of India with a special preference to Europe, the USA, Canada, and Australia. With increased awareness about Tibetan refugees and their problems, many countries have opened their borders to Tibetans by introducing numerous favourable policies. For instance, with the Immigration Act of 1990, the Tibetan community in New York grew exponentially. The US Congress authorised 1000 special visas for Tibetans under the Tibetan Provisions of the U.S. Immigration Act of 1990, leading to the rampant growth of Tibetan migrants in the US. The first 10 to 12 Tibetan immigrants arrived in the U.S. in the 1960s, and then hundreds in the 1970s. Today, New York alone consists of roughly 5,000 to 6,000 Tibetan immigrants.

Former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper agreed to resettle 1,000 Tibetans from Arunachal Pradesh in 2007 (CTA 2013) encouraging substantial migration. The fundamental intention of migration is to improve one’s well-being from the current state.

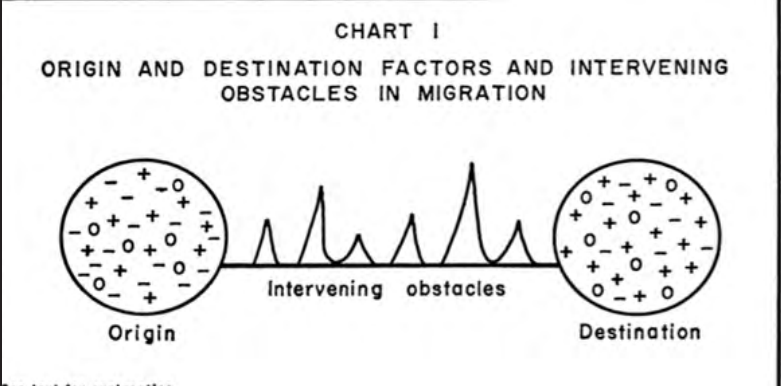

The motivation for migration can be analysed by correlating origin and destination places with push and pull aspects. Push factors in the place of origin generally include lack of opportunities, religious or political persecution, genocide, hazardous environmental conditions, etc. The pull factors at the destination, on the other hand, are environment responsive to the push variables. The flow of migrants between the two points is hindered by intervening obstacles or intervening opportunities, which can also affect the motivations of individuals while migrating.

Fig. 2 Lee’s (1966) push-pull theory in graphic form

Fig.2 shows there are two points in the flow of migration – a place of origin and a destination, with positive and negative signs indicating the variables of pull and push factors with intervening obstacles between them. Both the origin and destination have pluses and minuses which means each place has its push and pull aspects. Every migrant is influenced by the positives of staying and the negatives of leaving a particular place. The factors to which people are essentially indifferent are denoted as zeroes. The logic of the push-pull theory is that if the pluses (pulls) at the destination outweigh the pluses of staying at the origin, as shown above, then migration is likely to occur.

The three main pull factors or the aspects that pull Tibetans out of India are – economic opportunities, better policies for Tibetan refugees outside India, and world attention.

Better opportunities and more earning capacity are the primary reasons for the migration of Tibetan refugees out of India. They claim that there are better options, job security, better facilities, and more accessible resources. All this put together expands their level of awareness. People outside treat them as equals which makes the living situation a lot easier, whereas in India, except for a handful who are well educated, Tibetans are mostly given very low-paid jobs such as servants, waiters, cleaners, etc.

Second, concerning open policies in other countries, it can be argued that the migratory trend of Tibetans started in 1963 when Switzerland allowed 1,000 Tibetan refugees who were then the country’s first non-European refugees. Their population is now around 4,000. Further, in 1971, under the Tibetan Refugee Program (TRP), the original 240 Tibetans arrived in Canada, which now is a community of 5,000.

Third, the migrants and His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s transnational travels have helped to promote Tibetan culture and give the West exposure to the richness and traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetans also migrate to spread awareness. Sonam Wang due, a young Tibetan activist from India who was the President of the Tibetan Youth Congress in Dharamshala, says that he moved to the U.S. to protest more effectively and freely. An important day known as the Tibetan Lobby Day is conducted annually in the U.S, where hundreds of Tibetans along with their supporters assemble to urge their respective governments and parliamentarians to continue their support for Tibet and the Tibetan people.

Fig. 3 Tibetan Lobby Day in the U.S

On the other hand, some factors tend to push people away from their origin country. Push factors from India are mainly restrictions and social reasons. There are many Tibetan schools and colleges in the subcontinent with a large number of Tibetan students. According to the Planning Commission’s data on Tibetan Demography 2010, there is growing unemployment among Tibetan youth, with levels as high as 79.4 percent. When students return to their settlements after graduation, only 5 percent of them get absorbed in employment in the Tibetan community, as jobs here are scarce with mediocre salaries. Finding a job in the Indian community is further restricted by the authorization issue which holds that they are not Indian citizens. Many of them join the Indian Army, work in call centers, or become nurses as these are a few employment opportunities in which they can earn reasonably to support their families. Those without RC are restricted while applying for business documents and procuring licenses, and the youths who have acquired education and skills are pushed out of India as they search for better job opportunities. The younger generation of Tibetans in India realizes the discrimination they face and are motivated to migrate elsewhere for a better life. Although there is Article 19 of the Indian Constitution for freedom of speech and expression and the right to assemble peacefully, when it comes to Tibetans’ protesting, they are restricted in every possible way. Tibetans must secure a legal permit before any protest outside Tibetan settlements. This varies from one region to another, for instance, Tibetans in Dharamshala can protest peacefully as that is their officially recognized place by the Central government. In spite of having authorized Tibetan settlement areas in Chandigarh, Delhi, Arunachal Pradesh, Karnataka, etc., protests conducted in these states are not tolerated and require permits because the decision-making power is solely vested in each of the State governments.

According to Mr. Sonam Dagpo, a spokesperson for the CTA, the main reason for the decline of refugees in India is because “Tibetans are recognized as ‘foreigners’, not refugees”. The Indian government does not recognize Tibetans as refugees primarily because India is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention. This Convention relates to the status of refugees and is built on Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which recognizes the right of people seeking asylum in other countries because of persecution in their own countries. Another important reason is the lack of awareness among Tibetan refugees that they are the stakeholders to benefit from the TRP. However, implementation of the policy is left to the discretion of the respective States, which makes it problematic. Many Tibetans use India as a transit spot. They enter India primarily to meet His Holiness the Dalai Lama and study here, after which in pursuit of a better life and the West’s influence, they tend to resettle abroad. Nepal in recent times, generously funded by the Chinese, started strictly patrolling the borders with India and are sending back Tibetans to their homeland. Therefore, this is also one of the reasons why Tibetans entering India have decreased drastically.

The introduction of the Rehabilitation Policy (TRP) in India has decreased the burden on Tibetans. However, efforts are to be made to widen the level of awareness about the policy among the stakeholders and States

Conclusion

Egon F. Kunz (1981) theorized about refugee movements and formulated two categories of refugee migrants namely – ‘Anticipatory’ and ‘Acute’. Anticipatory migrants are people who flee in an orderly manner after a lot of preparation and having prior knowledge about the destination, the latter category of migrants is those who flee erratically due to threats by political or military entities and from persecution in their place of origin. Tibetans migrating out of India are largely Anticipatory refugee migrants well aware and seeking betterment. The introduction of the Rehabilitation Policy (TRP) in India has decreased the burden on Tibetans. However, efforts are to be made to widen the level of awareness about the policy among the stakeholders and States.

Tibetans are mostly living and visiting India from abroad by and large because of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Considering his advancing age and the number of Tibetans migrating out of India on the rise, will there be a time when Tibetans will give away the hold of solidarity by living in large communities in India? This is the burning question that lies ahead in the future of India-Tibet relations.

Feature Image Credits: Karnataka Tourism

Fig. 1 Source: https://reporting.unhcr.org/document/2681

Fig 2 Source: Dolma, T. (2019). Why are Tibetans Migrating Out of India? The Tibet Journal, 44(1), 27–52. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26921466

Fig 3 Source: https://tibetlobbyday.us/testimonials/2020-photographs/