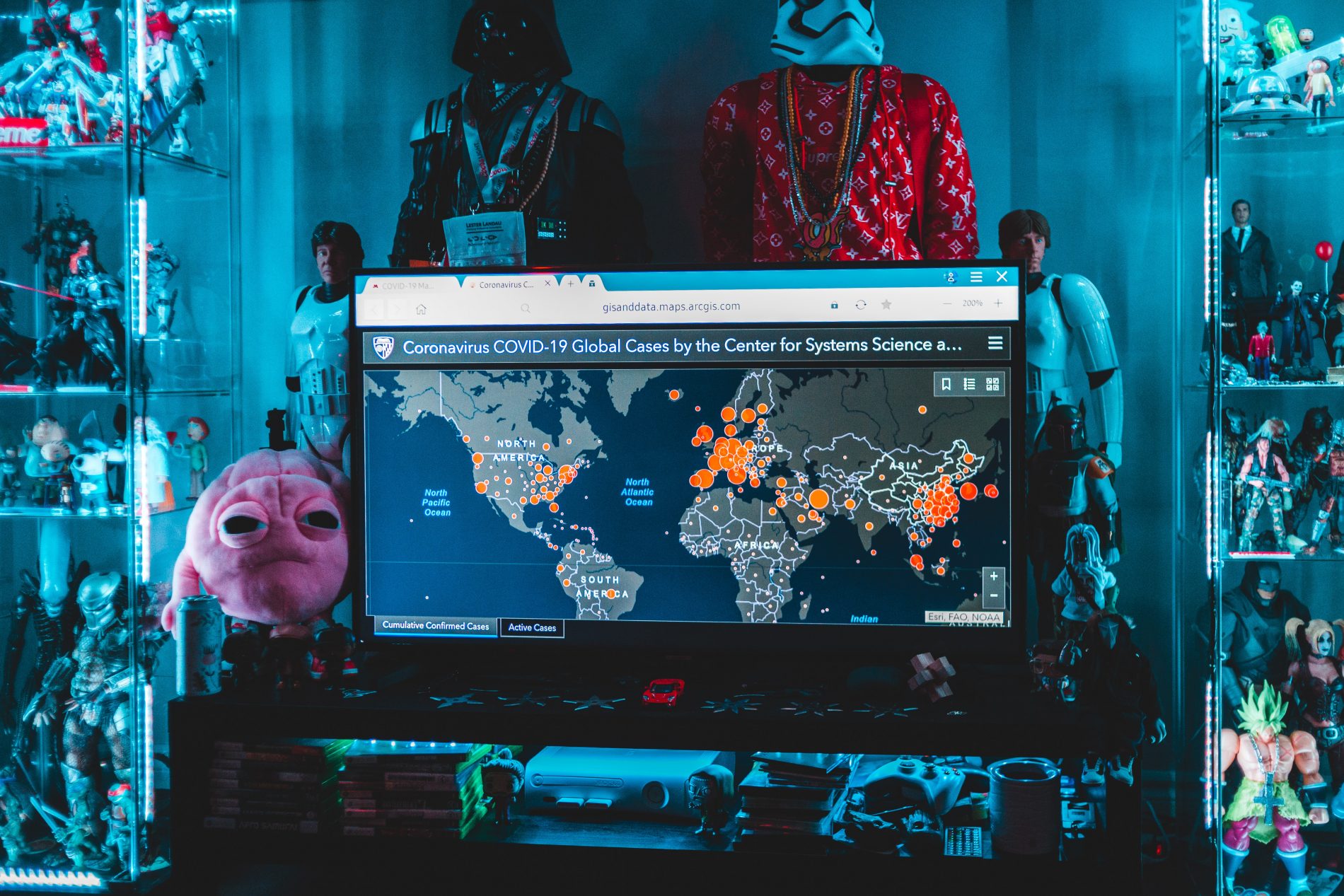

The world is engulfed in the ‘Corona Virus’ pandemic. As national health systems are being stretched to their limits, countries are closing their borders, banning travel, and isolating themselves…all in an international co-operative strategy to contain its spread and eliminate this pandemic. Andreas Herberg-Rothe sees valuable lessons in this international co-operation to be used to contain war and violence. Taking a leaf out of the broad ‘containment theory’ articulated by the late George Kennan in an anonymous article published in 1947 in the FP magazine, Andreas proposes a containment strategy for the world from the scourge of terrorism, religious fanaticism, and wars for world dominance (both proxy as well as interventions). This strategy for ‘common security’ can succeed only if it respects pluralism of cultures, religions, and social orders…M Matheswaran.

The initial measures against the spread of the new corona-virus could be summarized by one word – containment of the virus and hindering its spreading. This current prominence of the concept of containment could be used for other world problems. By having a closer look at the concept of containment it becomes obvious that it also included the concept of common security and cooperation – the same is true with the corona-virus. We are witnessing a worldwide expansion of war and violence, which should be countered by a new containment, just as George Kennan emphasized as early as 1987: “And for these reasons we are going to have to develop a wider concept of what containment means (…) – a concept, in other words, more responsive to the problems of our own time – than the one I so light-heartedly brought to expression, hacking away at my typewriter there in the northwest corner of the War College building in December of 1946.” Nearly seventy-five years have already passed, since George Kennan formulated his original vision of containment. Although his original concept would be altered, in application by various administrations of the US-Government, in practice it has been incorporated within the concept and politics of common security, which has been the essential complement to pure militarily containment. These ideas are still valid – and as Kennan himself pointed out, they are in more need of explication and implementation than ever.

The disinhibition of war and a new containment

The triumphant advance of democracy and free markets in the wake of the Soviet collapse seemed to be unstoppable, to the point where it appeared for a time as if the twenty-first century would be an age defined by economics and thus, to a great extent, peace. However, these expectations were quickly disappointed, not only because of the ongoing massacres and genocide in Africa, but also by the return of war to Europe (primarily in the former Yugoslavia), together with the attacks of September 11, 2001 in the USA, the Iraq war, the war in Syria with its on-going, violent consequences. A struggle against a new totalitarianism of an Islamic type appears to have started, in which war and violence are commonly perceived as having an unavoidable role. One can also speak of a new dimension to violence with respect to its extent and brutality – as exemplified by the extreme violence of the ongoing civil wars in Africa and the Middle East. Additionally we are facing completely new types of threats, for example the possession of weapons of mass destruction by terrorist organizations or the development of atomic bombs by “problematic” states like North Korea. The potential emergence of a new Superpower, China, and perhaps of new “great” powers like India may lead to a new arms race, which presumably have a nuclear dimension as well. In the consciousness of many, violence appears to be slipping the leash of rational control, an image the media has not hesitated for foster, especially with respect to Africa. Will there be “another bloody century,” as Colin Gray has proposed?

Although the current situation and the foreseeable future is not as immediately ominous as in the Cold War, it may be even worse in the long run. On one side, the prospect of planetary self-destruction via nuclear overkill, which loomed over the Cold War– and what could be worse than that, has been successfully averted. On the other hand, after having been granted a brief respite in the 1990s, mankind now feels itself to be confronting a “coming anarchy” of unknown dimensions and a new conflict between the US and China seems to be inevitable. If the horrific destructive potential threat of the Cold War has been reduced in scale, less cataclysmic possibilities have also become more imminent.

As compared to the Cold War, there is no longer an exclusive actor to be contained, as the Soviet Union was. Even if one were to anticipate China’s emergence as a new superpower in the next twenty years, it would not be reasonable, in advance of this actually happening, to develop a strategy of military containment against China similar to that against the Soviet Union in the 50s and 60s of last century, since doing so might well provoke the kind of crises and conflicts that such a strategy would be intended to avoid. The attempt to build up India as counter-weight to China and facilitating its nuclear ambitions, for instance, might risk undermining the international campaign to limit the proliferation of nuclear weapons in the world. Therefore we need quite another concept of containment, which could not be perceived as a threat to China.

The second difference is, that current developments in the strategic environment display fundamentally conflicting tendencies: between globalization and struggles over identities, locational advantages, and interests; between high-tech wars and combat with “knives and machetes” or suicide bombers; between symmetrical and asymmetrical warfare; between the privatization of war and violence and their re-politicization and re-ideologization as well as wars over “world order”; between the formation of new regional power centres and the imperial-hegemonic dominance of the only Superpower; between international organized crime and the institutionalization of regional and global institutions and communities; between increasing violations of international law and human rights on one side and their expansion on the other. A strategy designed to counter only one of these conflicting tendencies may be problematic with respect to the others. I therefore stress the necessity of striking a balance between competing possibilities.

The third difference is that the traditional containment was perceived mainly as military deterrence of the Soviet Union, although in its original formulation by George Kennan it was quite different from such a reductionism. Our main and decisive assumption is that a new containment must combine traditional, military containment on one side, and a range of opportunities for cooperation on the other. That’s not only necessary with respect to China, but even to the political Islam, in order to reduce the appeal of militant Islamic movements to millions of Muslim youth.

Such an overarching perspective has to be self-evident, little more than common sense, because it has to be accepted by quite different political leaders and peoples. The self-evidence of this concept could go so far that one could ask why we are discussing it. On the other hand, such a concept must be able to be distinguished by competing concepts. Last but not least, it should be regarded as an appropriate concept to counter contemporary developments. Finally, taking into account, that Kennan’s concept would not have succeeded, if it had been directed against the actions of the international community or the United States, it should be to some extend only brings to expression, what the international community is already doing anyway.

A concept that realized these demands of a political concept for contemporary needs was that of “common security”, developed in the 1970s. In the special situation of the cold war and of mutual deterrence this concept didn’t imply a common security shared among states with similar values and policies. On the contrary, this concept, perhaps developed for the first time by Klaus von Schubert, emphasized a quite different meaning. Traditionally, opponents have understood security as security from each other. The new approach laid down by Klaus von Schubert derived from the assumption, that in a world of multiple capacities of annihilating the planet, security could only be defined as common security. This small difference between security from each other and common security — shared security against a universal threat — was nothing less than a paradigm change in the Cold war.

The question of course remains, how to deter the true-believers, members of terrorist networks or people like the previous President of Iran, for whom even self-destruction may be a means of hastening millenarian goals. Of course, the “true-believers” or the “hard-core terrorist” could hardly be deterred. But this is just the reason, why containment should not be reduced to a strategy of deterrence. The real task even in these cases therefore is to act politically and militarily in a manner, that would enable to separate the “true believers” from the “believers” and those from the followers. This strategy can include military actions and credible threats, but at the same time it should be based on a double strategy of offering a choice between alternatives, whereas the reduction to military means would only intensify violent resistance. Additionally, even the true believers could be confronted with the choice, either further to be an accepted part of their social and religious environment (or to be excluded from them) or to reduce their millenarian aspirations. Of course, by following this strategy, there is no guarantee, that each terrorist attack could be averted. But this is not the real question. Assuming, that the goal of the terrorists and millenarian Islamists is to provoke an over-reaction of the West in order to ignite an all-out war between the West and the Islamic world, there is no choice than trying to separate them from their political, social and religious environment.

The concept of containment and contemporary warfare

The goal of the war on terror should not try to gain victory, because no one could explain, what victory would mean with regard to this special war. Moreover, trying to gain a decisive victory about the terrorists would even produce much more of them. The additional problem is not only, how we ourselves conceive the concept of victory, but even more important, in which ways for example the low-tech enemies define victory and defeat. That is an exercise, that requires cultural and historical knowledge much more than it does gee-whiz technology.

Instead one could argue, that the goal is “to contain terror”, which is of course something quite different from appeasement. An essential limitation of the dangers, posed by terrorist organizations could be based on three aspects: first, a struggle of political ideas for the hearts and minds of the millions of young people; second the attempt to curb the exchanges of knowledge, financial support, communication between the various networks with the aim of isolating them on a local level; and finally, but only as one of these three tasks, to destroy what one could label the terrorist infrastructure. In my understanding, trying to achieve victory in a traditional military manner would not only fail, but additionally would perhaps lead to much more terrorism in the foreseeable future.

The concept of the “centre of gravity” in warfare can provide another illustration of the way in which my conception makes a difference. Clausewitz defines war as an act of violence to compel our enemy to do our will. This definition suits our understanding of war between equal opponents, between opponents in which one side doesn’t want to annihilate the other or his political, ethnic or tribal body. But in conflicts between opponents with a different culture or ethnic background, the imposition of ones will on the other is often perceived as an attempt to annihilate the other’s community and identity. Hence, for democratic societies, the alternative is only to perceive war as an act of violence where, rather than compelling our own will to the opponent, your opponent is rendered unable any more to pursue his own will violently, unable to use his full power to impose his will on us or others. Consequently the abilities of his power must be limited, that he is no more able to threaten or fight us in order to compel us to do his will.

The purpose of containing war and violence, therefore, is, to remove from the belligerent adversary his physical and moral freedom of action, but without attacking the sources of his power and the order of his society. The key to “mastering violence” is to control certain operational domains, territory, mass movement, and armaments, but also information and humanitarian operations. But this task of “mastering violence” should no longer be perceived as being directed against the centre of gravity, but to the “lines” of the field of gravitation. Instead of an expansion of imposing one’s own will on the adversary up to the point of controlling his mind, as the protagonists of Strategic Information Warfare put it, the only way of ending conflict in the globalized 21st century is to set limits for action, but at the same time to give room for action (in the sense, Hannah Arendt used this term) and even resistance, which of course has the effect of legitimising action within those limits.

The overall political perspective on which the concept of the containing of war and violence in world society rests therefore consists of the following elements, the “pentagon of containing war and violence”:

▪ the ability to deter and discourage any opponent to fight a large scale war and to conduct pin-point military action as last resort,

▪ the possibility of using military force in order to limit and contain particularly excessive, large-scale violence which has the potential to destroy societies;

▪ the willingness to counter phenomena which help to cause violence such as poverty and oppression, especially in the economic sphere, and also the recognition of a pluralism of cultures and styles of life in world society;

▪ the motivation to develop a culture of civil conflict management (concepts which can be summed up with the “civilizational hexagon”, global governance, and democratic peace), based on the observation, that the reduction of our action to military means have proved counterproductive and would finally overstretch the military capabilities

and

▪ restricting the possession and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, their delivery systems, as well as of small arms, because the unhindered proliferation of both of them is inherently destructive to social order.

The position I have put forward is oriented towards a basically peaceful global policy, and treats the progressive limitation of war and violence as both an indefinite, on-going process and as an end in itself. The lasting and progressive containment of war and violence in world society is therefore necessary for the self-preservation of states, even their survival and of the civility of individual societies and world society.

Image Credit:Photo by Erik Mclean on Unsplash