Introduction

As the functions of the modern welfare state expand and the dependency of citizens on it increases, its services must be delivered in timely manner. To this end, the Delhi government developed a robust policy. Through the Delhi Act of 2011 (Right of Citizen to Time Bound Delivery of Services), referred to as “the Act”, and the Delhi (Right of Citizen to Time Bound Delivery of Services) Rules, 2011 [“the Rules”], it has guaranteed timely delivery of 361 services.[1] Delhi is not the only state to confer such a right. However, in these other states, the enforcement of this right requires physical presence. Delhi has used an e-Service Level Agreement [“e-SLA”] to digitise the entire enforcement process. Digitisation has enabled greater accountability, performance review, and convenience, whilst also reducing the invested time and cost of every stakeholder. Thus, through this e-governance tool, Delhi has developed a ‘new ecology’ for the citizen-state relationship.

In this paper, I will first provide a primer on both the Act and the e-SLA. In the second section, I will examine the constitutionality of the Act. Last, I will test the Act against the principles of good governance and citizen-centric administration.

Understanding the Act and e-SLA

The Act and e-SLA are deeply interrelated. While the Act defines the legal rights, procedures, and obligations, e-SLA is the mechanism for their execution. The Act comprises four major components: defined rights and corresponding liabilities, procedural prescriptions, the delegation of rulemaking, and the monitoring platform.

Every citizen is conferred with the right to time-bound delivery of services,[2] and a liability of compliance imposed on government servants.[3] In cases of default, the government servant is liable to pay the compensatory cost of ₹10 per day for the period of delay, subject to a maximum of ₹200 per application.[4] Correspondingly, citizens are entitled to recover the compensatory costs.[5]

The Act makes three different but interrelated procedural prescriptions. First, it provides the appointment process, eligibility criteria, and powers of the “competent officer”.[6] He/she must not be below the rank of Deputy Secretary or its equivalent rank and is empowered to impose a compensatory cost on the defaulting government servant. Second, it establishes the procedure governing fixation of liability.[7] If there is a delay, the aggrieved citizen can approach the competent officer, who immediately pays the cost that has been automatically calculated by e-SLA.[8] At a second stage, the officer issues show-cause notice to the concerned servant. If justifiable grounds exist, then the payment is debited from the government exchequer. Otherwise, it is reimbursed from the concerned servant. Third, it prescribes the appointment process, eligibility criteria, and powers of appellate authority as well as a 30-day time limit for filing an appeal. He/she must not be below the rank of Joint Secretary or its equivalent rank and has final authority on the matter.[9]

The Act provides for delegation of legislative authority in two senses. There is a power to make rules,[10] and the power to remove difficulties.[11] However, the exercise of these powers is subject to Parliamentary scrutiny.

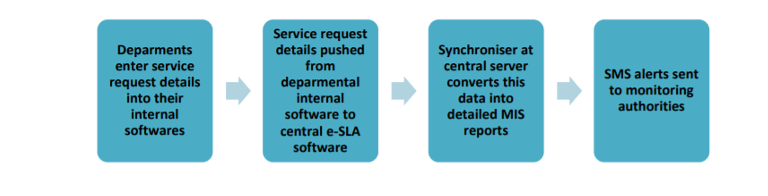

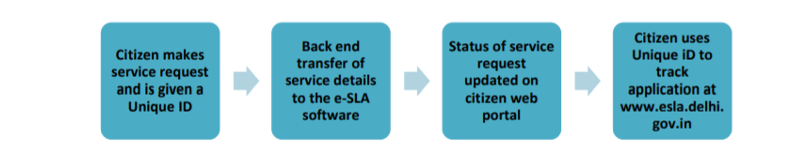

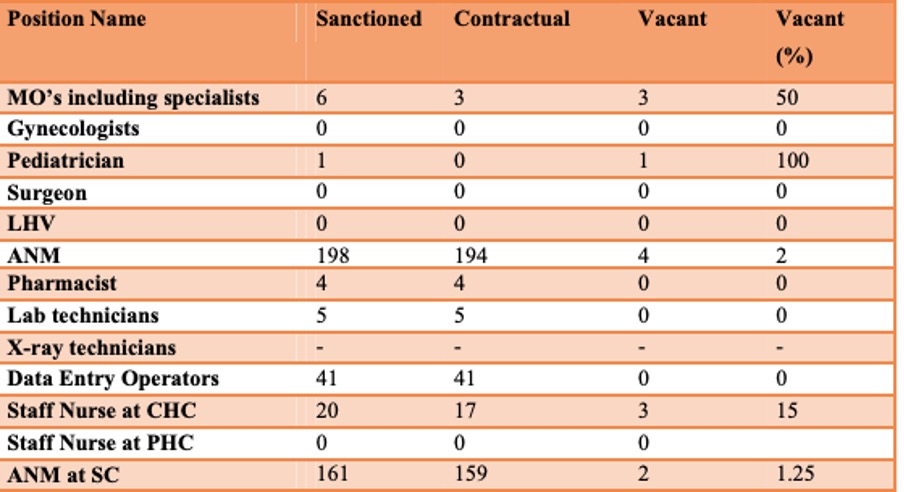

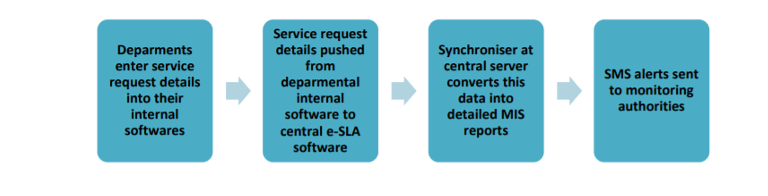

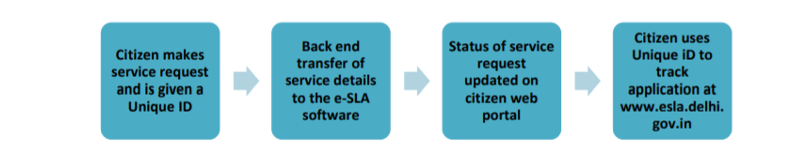

It is the duty of departments and local bodies to process the application of every citizen and provide an application number. Furthermore, these authorities are obligated to maintain and update the status of applications online.[12] The e-SLA monitoring system has been designated as an online database.[13] To the government, it provides detailed information on the number of disposed or pending cases, which helps in performance evaluation and corrective measures. To the citizens, it provides online facility to track their applications.[14] The information flow is explained below:

Figure 1: Information flow between government officials under e-SLA

Figure 2: Information flow between government officials and citizens under e-SLA

Constitutionality of the Act

The Constitution provides certain safeguards to “civil servants”.[15] At the outset, it must be noted that these employees are only a sub-set of the “government servants” defined in the Act.[16] Thus, the applicable scope of protection, if any, is not to the entire class of employees enumerated in the Act, but only to civil servants.

The legal issue herein is the constitutionality of imposing a compensation cost on the civil servant. This is a two-fold question:

- Whether there is the power to impose such a cost?

Appropriate legislatures are empowered to regulate the service conditions of civil servants.[17] As the cost relates to a service condition (i.e., timely delivery), the Delhi Legislative Assembly was empowered in imposing it.

- If so, has this exercise violated any constitutional safeguard?

However, this power is subject to constitutional safeguards guaranteed under Article 311.[18] The protection offered under Article 311(2) is exhaustive and with specific reference to the imposition of three penalties: dismissal, removal, and demotion.[19] Accordingly, the imposition of compensatory cost on the civil servant is beyond the scope of three-fold protection offered by Article 311. Thus, no constitutional safeguard has been violated herein.

As the imposition of compensatory cost on the civil servants is both within the power and compliant with safeguards, it is constitutional.

Testing the Act against principles of Good Governance and Citizen-Centric Administration

Governance refers to the process of decision-making, and the process of implementing those decisions.[20] Good governance is when these processes are tested against a normative standard. Citizen-centric administration refers to governance that places citizens at the centre of all administrative functions.[21] In this section, I will use the characteristics of good governance and the principles of citizen-centric administration as a collective standard[22] to analyze the process of formation and implementation of the Act, its Rules, and e-SLA.

Assessing Compliance in Formation and Implementation

a) Participatory. In the absence of statutory provisions, the administrative authorities are not bound to comply with any procedural norms, including notice and prior consultation with the interested parties. The Delhi Act, 2011 does not provide for any such consultation or ante-natal publicity. In the process of policy-making, there was participation only from the relevant government ministries and departments. The government did not take any active steps to broaden consultation to stakeholders such as the civic society organizations, labour unions, or even the general public.

The lack of participatory policy-making has directly impacted its awareness and enthusiasm among citizens. It was found that only 50% of the people know that their unique ID can be used to track their applications online. Further, only 15% of the people used their ID to track their application.[23]

b) Transparency. The e-SLA allows for complete transparency to the citizen as to the status of all his applications. The information is not only easily comprehensible but also accessible. However, the transparency does not extend to releasing statistics of operations to the public domain. Currently, these statistics, such as the figures on the number of applications, pendency, disposal rate, performing/underperforming departments, are accessible only to government officials.[24]

c) Responsiveness. The e-SLA system does not provide for any feedback mechanism. Thus, there is no avenue for the citizens availing these services to share their experiences. As feedback is the basis on which the system continually improves, this deficiency hinders the potential effectiveness of e-SLA.[25]

- Accountability

The right to time-bound service delivery through the mechanism of compensatory cost has, in theory, ensured that the government and its officials are accountable to citizens. This is buttressed by the fact that the Act seeks to develop a culture of timely delivery among the government servants by additionally punishing habitual offenders and providing cash incentives for those without a single default in a year.[26] However, the liability of government servant has been capped at ₹200, compared to other state legislation that penalizes in thousands. Further, the cash incentives are only up to ₹5000. Thus, the quantum is inadequate to cause attitudinal changes in the servants.

Moreover, there is no culture among public servants to hold their non-performing colleagues in disrepute.[27] There is no indication that this non-performance is factored into promotions. Anyhow, such public servants are typically complacent and not seeking promotions. The security of their present job and status is adequate incentive to persist with present behaviour. Thus, promotions and reputational loss among peers are not adequate incentives for performance either.

Furthermore, by releasing all relevant statistics of operations to the public domain, the government can broaden its accountability. These statistics can be used by stakeholders, such as news and media agencies and policy think-tanks, to supplement the government in identifying issues and corrective measures. This would also pressurize the government to be more proactive.

2. Consensus orientation

Through reasonable and extensively deliberated timelines, the Act sufficiently balances the interests of citizens in securing timely delivery with the government’s limited capacity.

3. Effectiveness and Efficiency

The usage of e-governance to guarantee the right to public service is a revolutionary process reform. This must be gauged at two levels:

- For the citizen, this system has reduced the number of physical visits required, thus saving time and cost. In a survey, 66.6% reported that they are not required to visit government offices more than once after submitting their applications.[28]

- For the government, it eliminates systemic errors and inefficiencies.[29] The statistics help in assessing performance and preparing corrective action.[30] However, if the system can track internal departmental processes too, it would allow determining the exact level at which service delivery is being delayed. Furthermore, the Act ignores the quality of timely delivered services.[31] To provide a comprehensive right to public service, the legislature must develop standards to assess the quality of services rendered on time.

4. Equitable and Inclusive

Under the Act, while the citizen is immediately compensated, the government servant is not immediately penalized for default. The procedure allows him/her to provide justified grounds that could excuse liability. For greater inclusivity, the government can prescribe a pro-rata calculation of the penalty. As the amount is automatically calculated by e-SLA, even complex formulas are acceptable.

5. Rule of Law

The Act provides for a fair legal framework and impartial enforcement.

Conclusion

Executing the right to time-bound service delivery through an online portal is truly revolutionary. It has emerged as model legislation for other governments. The Act is constitutionally valid. However, when tested against standards of good governance, this policy suffers from problems of non-participation, transparency, responsiveness, accountability, and effectiveness at the government-level. But it scores par excellence on the principles of consensus orientation, effectiveness at the citizen-level, inclusiveness, and rule of law. To embrace the truly revolutionary potential of this policy, the government must make the suggestions recommended in the last section of the paper, vis-à-vis each principle.

References:

[1] IANS, ‘245 services brought under Delhi time-bound delivery act’ (Business Standard, 24 August 2014) <https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ians/245-services-brought-under-delhi-time-bound-delivery-act-114082400707_1.html> accessed 17 January 2021.

[2] The Act, s. 3.

[3] The Act, s. 4.

[4] The Act, s. 7.

[5] The Act, s. 8.

[6] The Act, s. 9.

[7] The Act, s. 10.

[8] The Rules, r. 4(1).

[9] The Act, s. 11(1).

[10] The Act, s. 15.

[11] The Act, s. 16.

[12] The Act, s. 5.

[13] The Rules, r. 2(c).

[14] Arjun Kapoor & Niranjan Sahoo, India’s Shifting Governance Structure: From Charter of Promises to Services Guarantee (ORF Occasional Paper No 35, 2012).

[15] Constitution of India 1950, Art. 309, 310, 311.

[16] The Act, s. 2(g).

[17] Constitution of India 1950, Art. 309.

[18] Union of India v. S.P. Sharma (2014) 6 SCC 351.

[19] Yashomati Ghosh, Textbook on Administrative Law (1st edn, Lexis Nexis 2015) 416.

[20] UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, ‘What is Good Governance?’ <http://www. unescap.org/sites/default/files/good-governance.pdf>.

[21] Ghosh (n 19) 14.

[22] Second Administrative Reforms Commission, Citizen-Centric Administration (Report No 12, 2009) p. 8.

[23] Audit of Functioning of Government of Delhi’s e-SLA Scheme, by Management Development Institute, Gurgaon (2012).

[24] Ibid.

[25] Rohit Sinha, ‘Delivering on service guarantee: A case of Delhi’s e-SLA’ (ORF, 29 December 2012) <https://www.orfonline.org/research/delivering-on-service-guarantee-a-case-of-delhis-e-sla/> accessed 17 January 2021.

[26] The Act, s. 12.

[27] Kapoor & Sahoo (n 14); Amit Chandea & Surbhi Bhatia, The Right of Citizens for Time Bound Delivery of Goods and Services and Redressal of their Grievances Bill, 2011 (CCS, 2015) p. 25-26.

[28] Sinha (n 25).

[29] Chandea & Bhatia (n 27).

[30] Ibid.

[31] Kapoor & Sahoo (n 14).

Image Credit: Forbes India

First about Dr. Jackson. He was the first scientist to come up with the answer as to why mariners experience directional disorientation when they sail on vast seas. This navigational impairment, described by Jackson as ‘topological agnosia’ (literally, loss of knowledge about directions) was caused in his analysis by a distortion in an individual’s memory. An individual afflicted by this agnosia is found unable to remember to a destination known to him to be able to recall important landmarks seen a long time ago. Among the patients that Jackson studied were some women who knew where the London Bridge was, but they did not know how to go there from their homes. In their memory, the ‘little maps’ were forgotten, though the larger maps were inscribed in their brain. European colonial expansion was distinctly marked by this disorientation. When it was spreading south of Europe, the colonial powers thought of the south as ‘east’ and built a strong binary between the west and the east.

First about Dr. Jackson. He was the first scientist to come up with the answer as to why mariners experience directional disorientation when they sail on vast seas. This navigational impairment, described by Jackson as ‘topological agnosia’ (literally, loss of knowledge about directions) was caused in his analysis by a distortion in an individual’s memory. An individual afflicted by this agnosia is found unable to remember to a destination known to him to be able to recall important landmarks seen a long time ago. Among the patients that Jackson studied were some women who knew where the London Bridge was, but they did not know how to go there from their homes. In their memory, the ‘little maps’ were forgotten, though the larger maps were inscribed in their brain. European colonial expansion was distinctly marked by this disorientation. When it was spreading south of Europe, the colonial powers thought of the south as ‘east’ and built a strong binary between the west and the east.