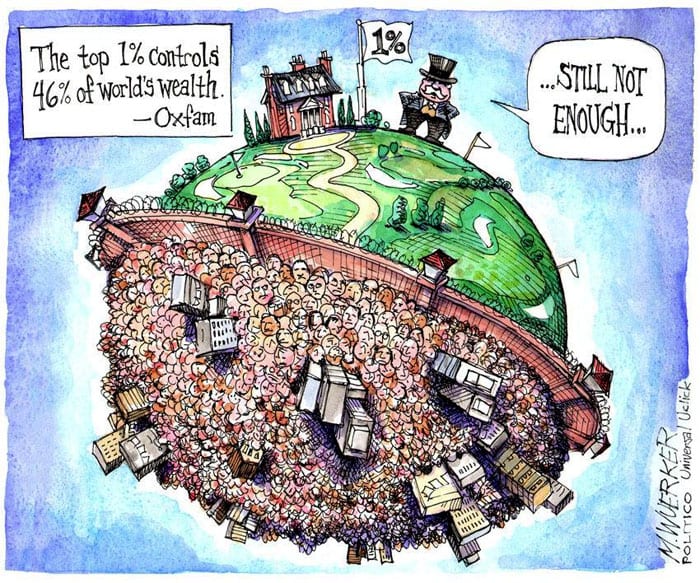

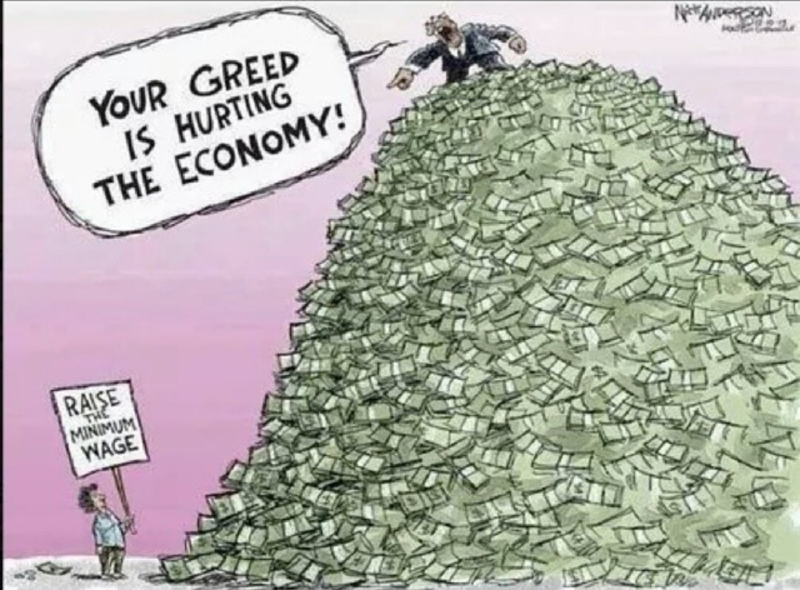

Neoliberalism is the dominant form of capitalism that began in the 1980s as a way to promote global trade and grow all economies. That was a false promise, whereas in essence it supported individuals amassing massive wealth in the name of market forces, at the expense of common man by ensuring states minimise their role and eliminate welfare economics. It ensured least-developed and developing economies remained resource providers to developed economies, exemplifying extraction and exploitation. Neoliberalism is a top down economic policy that does not benefit those who are impoverished. The inequality we see on a global scale is mind-numbing. In 2006, the world’s richest 497 people were worth 3.5 trillion US dollars representing 7% of the world’s GDP. That same year, the world’s lowest income countries that housed 2.4 billion people were worth just 1.4 trillion US dollars, which only represents 3.3% of the world’s GDP. The situation today is far worse as Andreas Herberg-Rothe explains in his critical analysis below. The world is in urgent need of freeing itself from the clutches of neoliberal capitalism.

..neoliberalism contains a general tendency towards an extensive economisation of society. Thus, inequality transcends the economy and becomes the dominant trend in society, as in racism, radical extremism, and hate ideologies in general: Us against the rest, whoever the rest may be.

Following on from the initial question about Hannah Arendt’s thesis that equality must be confined to the political sphere, we must ask how democracy and human rights can be preserved in the face of social inequality on an extraordinary scale. By the end of this century, 1% of the world’s population will own as much as the “rest” of the other 99%. And already today, only 6 people own more property than 3.6 billion. Let us take a closer look at some of the ideas of the currently dominant neo-liberalism, which sheds some light on the acceptance of these current obscene inequalities. For this ideology, social inequality is a means to greater wealth. However, since it sets no limits on social inequality, it can be used to legitimize even obscene inequalities. We argue that neoliberalism as an ideology is the result of the spread of a specific approach to economic thought that has its roots in the first half of the twentieth century, when Walter Lippmann’s seminal book “An Inquiry into the Principles of the Good Society” (1937), followed by Friedrich August von Hayek’s “The Road to Serfdom” (1944), gave rise to neoliberalism. During the Cold War period, neoliberals gained more and more ground in establishing a global system. With the support of Milton Friedman and his “Chicago Boys,” the first attempt to establish a pure neoliberal economic system took place in Chile under the military dictatorship of General Pinochet in the 1970s. In the last decade of the Cold War, neoliberal architects such as Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan began to impose the new economic model. Since the end of the Cold War, the final development was that neoliberalism became THE hegemonic economic system, as capitalism was de jure allowed to spread unhindered worldwide, and neoliberalism continued on its way to becoming the dominant belief system.

The critical message in this sense is the following: This process is not limited to an economic dimension – neoliberalism contains a general tendency towards an extensive economisation of society. Thus, inequality transcends the economy and becomes the dominant trend in society, as in racism, radical extremism, and hate ideologies in general: Us against the rest, whoever the rest may be.

When we talk about global inequality in the era of neoliberalism, we are referring to two other major developments: To this day, inequality between the global North and South persists. While the total amount of poverty has decreased, as seen in the World Bank’s report (2016), there is still a considerable gap between those countries that benefit from the global economy and those that serve as cheap production or commodity areas. The second development takes place in countries that are more exposed to the neoliberal project. In this sense, societies are turning into fragmented communities where the “losers of neoliberalism” are threatened by long-term unemployment, a life of poverty, social and economic degeneration.

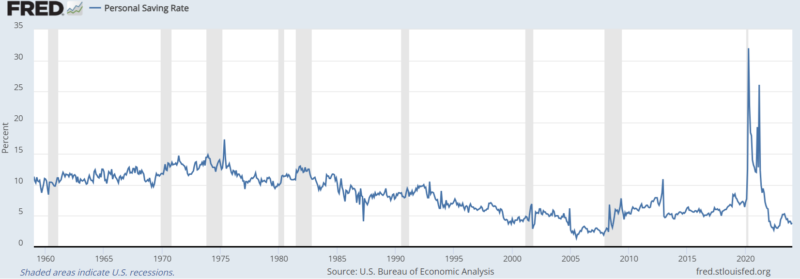

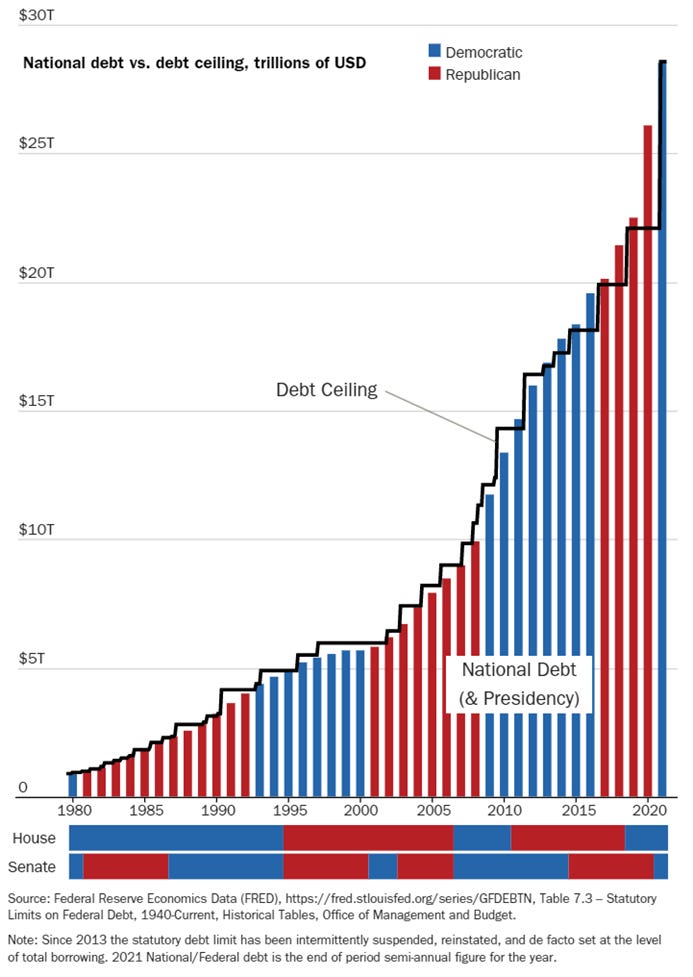

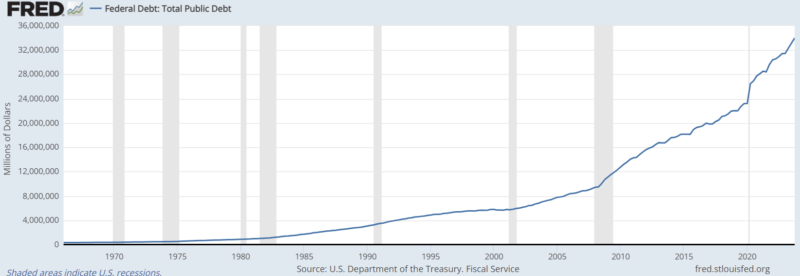

After three decades of intense global neo-liberalism, the result has been a significant increase in social inequalities, polarization and fragmentation of societies (if not the entire world society), not to mention a global financial crisis in 2008 caused by escalating casino capitalism and the policies of a powerful global financial elite.

We are witnessing a global and drastic discontent of peoples, fears and anger, feelings of marginalization, helplessness, insecurity and injustice. After three decades of intense global neo-liberalism, the result has been a significant increase in social inequalities, polarization and fragmentation of societies (if not the entire world society), not to mention a global financial crisis in 2008 caused by escalating casino capitalism and the policies of a powerful global financial elite. We witness a global and drastic dissatisfaction of the peoples, fears, and anger, the feelings of marginalization, helplessness, insecurity, and injustice. After three decades of intense worldwide Neo-Liberalism, the result significantly intensified social inequalities, polarization, and fragmentation of societies (if not the entire world society), not to mention a global financial crisis in 2008 caused by escalating casino capitalism and the policy of a powerful global finance elite.

The central critique is that neoliberalism includes social inequality as part of its basic theory. Such capitalism emphasizes the strongest/fittest (parts of society) and uses inequality as a means to achieve more wealth.

Remarkably and frighteningly, the situation outlined does not provoke the oppressed, marginalised, and disadvantaged populations to turn against their oppressors and their exploitation. These people tend to sympathize with ideological alternatives, either with more triumphant (right-wing) populist movements and parties or are attracted by radical/fundamentalist religious groups such as the Islamic State. The result is an increase in polarization and violence, and even more protracted wars and religious-ideological disputes. Europe is not exempt from the trend toward obscene social inequality. We also find a polarization between rich and poor, between those who have good starting conditions and those who have little chance of prosperity, between those who are included and those who feel excluded. The fact that Europe has so far largely avoided populist parties gaining administrative power (although we have already witnessed this process in France, Hungary and Poland) may be due to the remnants of the welfare state. In this respect, at least a minimum of financial security remains and limits the neoliberal trend. In the United States, on the other hand, a flawless populist could reach the highest office. The people, stuck in their misery, fear and insecurity, voted for a supposed alternative to the neoliberal establishment, but above all against other social outcasts whom they blamed for their misery. This brings us to the central critique of neoliberalism, a system that has caused fundamental social oddities, the impact of which as an ideology has been highlighted above. The central critique is that neo-liberalism includes social inequality as part of its basic theory. Such capitalism emphasizes the strongest/fittest (parts of society) and uses inequality as a means to achieve more wealth.

In an interview with the German magazine Wirtschaftswoche, Hayek spoke bluntly about the neoliberal value system: He emphasizes that social inequality, in his view, is not at all unfortunate, but rather pleasant. He describes inequality as something simply necessary (Hayek, 1981). In addition, he defines the foundations of neo-liberalism as the “dethronement of politics” (1981). First, he points out the importance of protecting freedom at all costs (against state control and the political pressure that comes with it). The neoliberals see even a serious increase in inequality as a fundamental prerequisite for more economic growth and the progress of their project. One of the most renowned critics of neoliberalism in Germany, Christoph Butterwegge (2007), sees in this logic a perfidious reversal of the original intentions of Smith’s (reproduced in 2013) inquiry into the wealth of nations in the current precarious global situation. The real capitalism of our time – neoliberalism – sees inequality as a necessity for the functioning of the system. It emphasizes this statement: The more inequality, the better the system works. The hardworking, successful, and productive parts of society (or rather the economy) deserve their wealth, status, and visible advantage over the rest (the part of society that is seen as less strong or less ambitious). The deliberate production of inequality sets in motion a fatal cycle that leads to the current tense global situation and contributes to several intra-societal conflicts.

The market alone is the regulating mechanism of development and decision-making processes within a society dominated by neo-liberalism, and as such is not politics at all. This brings us closer to the relationship between neoliberalism and democracy. The understanding of democracy in neoliberal theory is, so to speak, different. Principles such as equality or self-determination, which are prominent in the classical understanding of democracy, are rejected. Neo-liberalism strives for a capitalist system without any limits set by the welfare state and even the state as such, in order to shape, enforce and legitimize a society dominated only by the market economy. Meanwhile there are precarious tendencies recognizable, where others than the politically legitimized decision-makers dictate the actual political and social direction (e.g. the extraordinarily strong automobile lobby with VW, BMW and Mercedes in Germany or big global players in the financial sector like the investment company BlackRock). Neoliberalism only seemingly embraces democracy. The elementary democratic goals (protection of fundamental and civil rights and respect for human rights) can no longer be fully realized. Democracy cannot defend itself against neo-liberalism if political decision-makers do not resolutely oppose the neo-liberal zeal for expansion into all areas of society. The dramatic increase in inequality coincides with the failure of the state as an authority of social compensation and adjustment, as neoliberalism eliminates the state as an institution that mediates conflicts in society. To put it in a nutshell: Whereas in classical economic liberalism the state’s role is to protect and guarantee the functioning of the market economy, in neoliberalism the state must submit to the market system.

Our discussion of neoliberalism here is not about this conceptualization and its history, which would require a separate article. Nevertheless, we want to emphasize that in neo-liberalism, social inequality is a means to achieve more wealth for the few. Therefore, we argue that there must be a flexible but specific limit to social inequality in order to achieve this goal, while excessive inequality is counterproductive.

As noted above, moderate levels of inequality are not necessarily wrong per se. In a modern understanding, it also contributes to a just society in which merit, better qualifications, greater responsibility, etc. are rewarded. The principle of allowing differences, as used in the theory of the social market economy, is a remarkably positive one when such differentiation leads to the well-being of the majority of people in need. However, neo-liberalism adopts a differentiation that intensifies inequality to a very critical dimension. The current level of social inequality attacks our system of values, endangers essential democracy, and destroys the social fabric of societies. Even if we consider a “healthy” level of inequality to be a valuable instrument for a functioning market society, what has become the neoliberal reality has nothing to do with such an ideal. Neoliberalism implies an antisocial state of a system in which inequality is embedded in society as its driving mechanism. Consequently, we witness a division between rich and poor in times of feudalism. A certain degree of social equalization through the welfare state and a minimum of social security is no longer guaranteed. The typical prerequisites today are flexibility, performance, competitiveness, etc. – In general, we see the total domination of individualism within neo-liberalism, leading to the disintegration of society. In one part of the world, mainly in the Global South, we observe the decline of entire population groups. In contrast, in other parts of the world we see fragmented societies in hybrid globalization and increasing tendencies towards radical (religious) ideologies, violence and war.

It must be acknowledged that neoliberalism was one of the causes of the rise of the newly industrialized nations, but the overemphasis on individual property also contributes to obscene inequality and thus to the decline of civilized norms.

The Polish-British sociologist Zygmunt Bauman summed up this problem by comparing it to the slogan of the French Revolution: “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité”. According to the proponents of the time, each element could only be realized if all three remained firmly together and became like a body with different organs. The logic was as follows: “Liberté could produce Fraternité only in company with Egalité; cut off this medium/mediating postulate from the triad – and Liberté will most likely lead to inequality, and in fact to division and mutual enmity and strife, instead of unity and solidarity. Only the triad in its entirety is capable of ensuring a peaceful and prosperous society, well integrated and imbued with the spirit of cooperation. Equality is therefore necessary as a mediating element of this triad in Bauman’s approach. What he embraces is nothing less than a floating balance between freedom and equality. It must be acknowledged that neoliberalism was one of the causes of the rise of the newly industrialized nations, but the overemphasis on individual property also contributes to obscene inequality and thus to the decline of civilized norms. When real socialism passed into history in 1989 (and rightly so), the obscene global level of social inequality could be the beginning of the end (Bee Gees) of neo-liberalism, centered on the primacy of individual property, which is destroying the social fabric of societies as well as the prospects for democratic development. Individual property is a human right, but it must be balanced with the needs of communities, otherwise it would destroy them in the end.

Feature Image Credit: cultursmag.com

Cartoon Image Credit: ‘Your greed is hurting the economy’ economicsocialogy.org