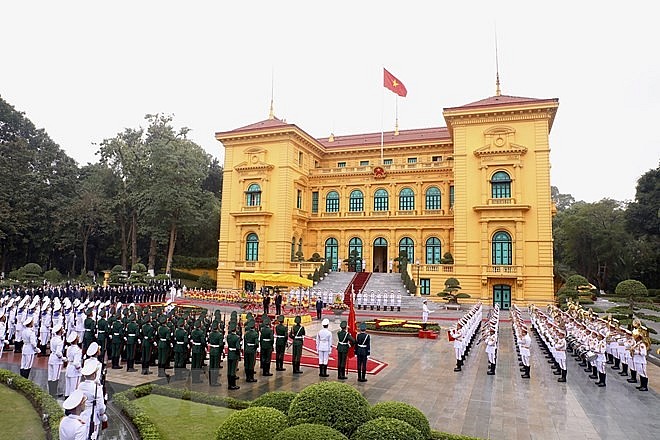

The year 2022 is singularly important for Vietnam-Lao PDR relations. It marks the 60th anniversary of the bilateral diplomatic relations, and 45 years of the Vietnam-Laos Treaty of Amity and Cooperation. Both sides have accorded high priority to the current year, and Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh extended the invitation to Lao Prime Minister Phankham Viphavanh to visit to commemorate the above events. Accordingly, Prime Minister Viphavanh is in Vietnam and is leading a high-level delegation.

Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh, according to reports, will also co-chair the 44th meeting of the Vietnam-Laos Inter-Governmental Committee and launch the Vietnam-Laos Solidarity and Friendship Year 2022. This would help to “get a better understanding of each other’s socio-economic situation, development orientations and external policies” particularly during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The visit is also intended to boost Vietnam-Laos cooperation strategy for the 2021-2030 period and the five-year cooperation plan for the 2021-2025 period that are now into the second year and involve bilateral engagements in multiple domains such as politics, diplomacy, security-defence, economy, science-technology, culture, and education-training.

COVID-19 would be high on the agenda of both leaders given that the pandemic is impacting their countries. They are in the midst of the fourth wave with 8,236 and 354,075 active cases (as of 05 Jan 2022) respectively.

In December 2021, the Lao government announced opening up of the country for trade and tourism in three phases: First phase – January 1, 2022; Second phase – April 1, 2022; and the Third phase July 1, 2022. In the first phase, 17 countries, including Vietnam and many neighbouring ASEAN countries, besides some European countries, China, the US, Australia and Canada would be welcomed. The Lao economy is impacted by COVID-19 and was projected to grow at 3 per cent, a figure lower than 4 per cent as approved by the Laotian National Assembly. This attributed to the pandemic and prolonged lockdowns that disrupted economic activities and companies, retail and wholesale shops had to shut down.

Leaders in Vientiane recognize the importance of regional development particularly in the Cambodia-Laos-Vietnam Development Triangle Area (CLV-DTA)

Vietnam and Lao PDR are also engaged in major connectivity projects. Lao is a landlocked country and ports in Vietnam provide the country access to the sea to engage in international seaborne commerce.

Last year, during President Nguyen Xuan Phuc visit to Laos, 14 agreements spanning a wide range of issues were signed. The leaders agreed to fast-track joint projects including Vung Ang No.1, 2, 3 port projects, the Hanoi-Vientiane Expressway, Vientiane-Vung Ang Railway, Lao-Vietnam Friendship Park in Vientiane, Nongkhang Airport and hospitals in Lao Houaphan and Xiangkhouang Provinces.

One of their flagship joint projects is the 1,450 kilometres long East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC). It is a road-building project and is supported by the Asia Development Bank (ADB). Its western leg includes Thailand, and in the east, it terminates at the Vietnamese port of Da Nang which is a major gateway to the Pacific.

Similarly, the 555 kilometres railway link (452 kilometres in Laos and 103 kilometres in Ha Tinh central province in Vietnam) between Vientiane and the Vietnamese deep-water port of Vung Ang is important. It gives Laos yet another access to the sea. Importantly, it is being jointly developed and Laos would hold a 60% stake in the project, and Vietnam with 40%.

China is also engaged in connectivity projects in Laos. In December 2021, after six years of construction, the Laos-China Railway project was finally operationalized. It is a complex project and includes 61 kilometres of bridges and 198 kilometres of tunnels and reduce travel time between Vientiane to the Chinese border from 15 hours by road to four hours. It will be operated by the Laos-China Railway Co., a joint venture between China Railway group and two other Chinese government-owned companies with a 70% stake and a Laotian state company with 30%.

Vietnam offers Laos an alternative to Chinese infrastructure investments and it ranks third among investors in Lao with total investments of US$ 5.16 billion in 209 projects. There are fears that the Chinese funded projects do not generate economic benefits for Laos, instead these only benefit China.

There are geopolitical dynamics at play in the CLV-DTA that are targeted against China, and Cambodia and Laos acknowledge Vietnam’s leadership

Vietnam cannot match up with the Chinese investments in Laos, but leaders in Vientiane recognize the importance of regional development particularly in the Cambodia-Laos-Vietnam Development Triangle Area (CLV-DTA). Vietnam for example has invested nearly US$ 4 billion in Cambodia and as noted above over US$ 5 billion in Laos. It is fair to assume that there are geopolitical dynamics at play in the CLV-DTA that are targeted against China, and Cambodia and Laos acknowledge Vietnam’s leadership.

Images Credit: Vietnam times