Let us all unite and toil together

To give the best we have to Africa

The cradle of mankind and fount of culture

Our pride and hope at break of dawn

From the African Union anthem

Consider this scenario, courtesy of Supreme Africa Breaking News: Since 2022, representatives of the African Union have been meeting at the organisation’s headquarters in Addis Ababa to draw up a living constitution for the continent and establish a single African government. The constitution itself will be promulgated in 2026, whereupon national lawmaking bodies will begin aligning domestic laws within the continental framework and African governments will sign that one African sovereign agreement. Between then and 2028, citizens will receive dual IDs, a unified army will be created, and countries will begin using a common digital currency—Afrigold—alongside their local ones. The third stage, harmonization, will culminate in 2035, when the newly formed African parliament will gain real powers.

After that, Africans will be free to move around the continent to live and work where they please. They will be able to appeal to AU courts if their government violates their rights, and they will be able to vote in the elections of whichever country they happen to find themselves. Democracy will be the default system of government for all member states, even though monarchies will participate in an advisory capacity in a council of sovereigns, alongside chiefs and spiritual leaders. In the words of Mama Pan Africa, an invented muse of sorts, “This constitution respects the soil it walks on. We’re not killing traditions; we’re aligning them with the dream.”

Alas, a dream it is indeed. Supreme Africa Breaking News is a YouTube channel of true believers. And the reality of the AU could hardly be harsher.

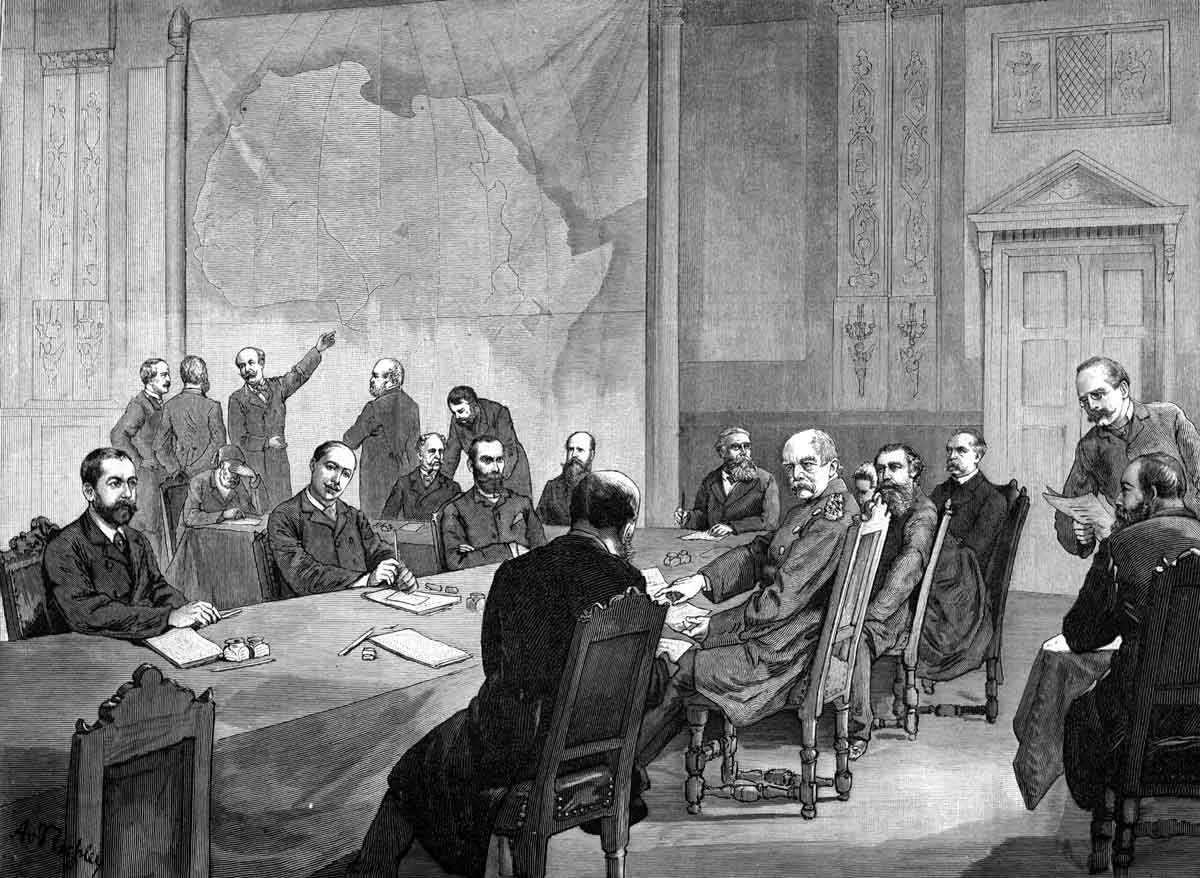

The first and most obvious problem is the historical legacy of colonialism, which, by the end of the nineteenth century had divided the continent into several dozen territories under the control and administration of mostly the UK and France, but also Belgium, Portugal, Spain, and, for a time, Germany. Following World War II—which had been fought in the name of saving the world from tyranny—these states all gained what they were pleased to call independence, with their own flags, anthems, and UN seats. But what did that amount to in practice?

In July 1960, Michel Debré, then the prime minister of France, stated to the leader of Gabon: “Independence is granted on the condition that the State, once independent, undertakes to respect the cooperation agreements signed previously. There are two systems which come into force at the same time: independence and cooperation agreements. One does not go without the other.”

In short, as the historian Tony Chafer has put it, “decolonisation did not mark an end, but rather a restructuring of the imperial relationship.”

The French didn’t fudge the answer. In July 1960, Michel Debré, then the prime minister of France, stated to the leader of Gabon: “Independence is granted on the condition that the State, once independent, undertakes to respect the cooperation agreements signed previously. There are two systems which come into force at the same time: independence and cooperation agreements. One does not go without the other.” In short, as the historian Tony Chafer has put it, “decolonisation did not mark an end, but rather a restructuring of the imperial relationship.” The cooperation agreements had a number of components. One was the issue of what was known as the colonial debt—which, however counterintuitive this may seem today, obliged the newly independent countries to pay for the infrastructure supposedly built by France during colonisation. There was also the obligation for them to continue using French as the national language. And there were the security pacts under which they would have to support the mother country in any future wars.

Even more telling was the right of first refusal on the purchase of all natural resources (including those yet to be discovered) in ex-colonial territories that France reserved for itself, irrespective of whether the new countries’ governments could secure better deals elsewhere. And there was the imposition of the CFA franc on fourteen West and Central African states (including Guinea-Bissau, a former Portuguese colony) at a fixed exchange rate with the French franc (and subsequently, the euro). This setup enabled France to pay for imports in its own currency and thereby save on any currency exchanges in a world otherwise dominated by the US dollar. The French economy benefitted greatly from the ensuing trade surplus, which fed reserves to pay for the country’s debts. Some African leaders profited as well: they could more easily loot their respective treasuries, with the active encouragement of their French masters, who also guaranteed their grip on power by keeping French troops stationed near the capital cities. Those who attempted to skirt any of the requirements were quickly disposed of.

Such was the case with Togo. In 1963, barely two years into his tenure as the country’s first president, Sylvanus Olympio was assassinated by a squad of soldiers led by Gnassingbé Eyadéma, an army sergeant and former French Foreign Legionnaire. Olympio’s crime, in the eyes of the French authorities, was to have insisted that Togo should have its own currency. Eyadéma soon handed power over to a new president, only to overthrow him four years later, in 1967. Subsequently, he morphed into a civilian president, and following growing unrest after a decade in power in that capacity, he agreed to a democratic constitution—and then easily won multiparty elections in 1993 and again in 1998, both times amid widespread allegations of electoral fraud. Term limits should have forced him to finally step down in 2002, but he had the constitution amended to abolish them, and he won elections again in 2003, and again was accused of fraud. He died in office two years later. In all of this, he was fully supported by successive French governments—much like his son Faure Gnassingbé has been since.

Gnassingbé, who had served as a minister under his father, in 2005 promptly took over the mantle in what was effectively a military coup. Like his father, he served two terms, the new constitution’s stipulated maximum, and then, also like his father, he rewrote the constitution—this time converting the presidential system to a parliamentary one. As the new prime minister, Gnassingbé was named president of the council of ministers, with most of the previous powers of the president devolving to him. He could stay in this post until at least 2030.

As it happens, a similar path is currently being trod by Alassane Ouattara, since 2010 the president of Côte d’Ivoire, the jewel in the Françafrique crown. Ouattara is now proposing to stand for re-election for a fourth term, arguing that term limits were reset to zero with a new constitution in 2016. As I write, protestors are being shot on the streets in both countries. President Emmanuel Macron of France recently denied that he had asked Gnassingbé to resign, despite reports to the contrary; where Ouattara is concerned, Macron had said, in 2020, “France does not have to give lessons.” France is anxious to maintain a neocolonial relationship, but Macron understands very well that it cannot be sustained, and so he hedges.

By contrast, the best that can be said for the British during decolonisation is that they were more circumspect than the French. The new native rulers weren’t required to sign a piece of paper: They had already been co-opted into service, most glaringly in the case of Nigeria. According to the historian Olakunle Lawal, in the runup to independence in 1960, a draft paper from the British Foreign Office sought to investigate how “we can sustain our position as a world power, particularly in the economic and strategic fields, against the dangers inherent in the present upsurge of nationalism,” in order that the UK might “maintain specific British interests on which our existence as a trading country depends.” It concluded that the challenge “was to forestall nationalist demands which threaten our vital interests” by creating “a class with a vested interest in co-operation.” But then the British authorities knew with whom they were dealing.

Following independence, this class proceeded to loot the Nigerian treasury to the tune of $20 trillion between 1960 and 2005, storing many of the proceeds in safe havens abroad. Nigeria still ranks among the most corrupt countries in the world, according to Transparency International. Such behaviour is a sign of these people’s contempt for the masses they lord it over—and sometimes, indeed, are allowed to lord it over by those masses themselves.

Consider the case of Ike Ekweremadu, a former long-time senator and former deputy president of the Senate, who is serving a prison sentence in the U.K. after being convicted of an organ-trafficking plot, the first such case to be tried under the 2015 Modern Slavery Act. It turns out that he had arranged for a 21-year-old street hawker in Lagos to travel to the UK so that one of the vendor’s kidneys could be harvested to save the life of Ekweremadu’s ailing daughter. The operation would have cost Ekweremadu £80,000—small change for someone with two homes in London, three in Florida, and seven in Dubai. The intended victim, who was to receive just £7,000 for his organ, only realised what was about to be done to him when doctors informed him of the medical risks he faced and the subsequent lifelong care he would require. Ekweremadu clearly didn’t think much of the fellow’s life; after all, the man had only been selling phone accessories out of a wheelbarrow in Lagos.

That young man has now improved his lot, having inadvertently been gifted a one-way ticket to the so-called developed world, which mercifully granted him asylum for his travails. Tellingly, however, Ekweremadu’s wife, who was convicted alongside her husband but has since been released, was enthusiastically received when she returned home to Nigeria early this year. In the words of a local community leader: “Our prayers are with the Ekweremadu family, and we hope Senator Ike will also be reunited with us soon.” No mention of their target.

So here we are, all these decades after so-called independence, and what is the role of the African Union in all of this? Originally known as the Organization of African Unity, the body was launched in 1963 with five objectives: to promote unity and solidarity among African states; to defend their sovereignty, territorial integrity, and independence; to coordinate and intensify their efforts to achieve a better life for the peoples of Africa; to eradicate all forms of colonialism; and to promote international cooperation, with due regard to the Charter of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Of these goals, the first was by far the most important. Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first head of state, spelt this out in an impassioned speech to the OAU in 1963: “Unite we must. Without necessarily sacrificing our sovereignties, big or small, we can here and now forge a political union based on defence, foreign affairs and diplomacy, and a common citizenship, an African currency, an African monetary zone, and an African central bank. We must unite in order to achieve the full liberation of our continent.”

Yet little or no progress was made on this front. In time, the OAU became known as an old men’s club, because of elderly African leaders who were more concerned with oppressing their subjects in the artificial fiefs they had inherited than with uplifting their lot. And many of those fiefs, though many are also actual countries, are still too insignificant in the larger scheme of things: six contain fewer than one million people, four fewer than two million, and another five fewer than three million. Which is one reason the heads of state or government of the OAU issued the Sirte Declaration in 1999 calling for the establishment of the AU: they wanted to accelerate the integration of Africa so that, according to one commentator on the site of the Nasser Youth Movement, the continent could “play its rightful role in the global economy while addressing multifaceted social, economic and political problems compounded as they were by certain negative aspects of globalization.” All well and good.

And this wish was reiterated by Dr. Arikana Chihombori-Quao, the AU’s ambassador to the U.S. in 2016–19: “Until Africa comes together as a continent to speak with one voice as a people, nothing will change for the good of her people.” Failing that, she pointed out—obviously enough—that a plethora of small, unviable countries with “the same sovereignty as China, as India,” were deliberately designed “to see to it that they will never make it on their own—and in the event those countries do make it, they are easy to destabilise.”

“The dismissal of Arikana Chihombori-Quao, AU ambassador to the United States, raises serious questions about the independence of the AU. For someone who spoke her mind about the detrimental effects of colonisation and the huge cost of French control in several parts of Africa, this is an act that can best be described as coming from French-controlled colonised minds.” – Jerry John Rawlings, former President of Ghana

Shortly after, her term was abruptly cut short without explanation. The chair of the AU at the time, Moussa Faki Mahamat, a former foreign minister of Chad, wrote her a letter that read, in part: “I have the honor to inform you that, in line with the terms and conditions of the service governing your appointment as Permanent Representative of the African Union Mission to the United States in Washington, DC, I have decided to terminate your contract in that capacity with effect from Nov. 1, 2019.” To many, this was proof of the AU’s spinelessness in the face of the West. Jerry John Rawlings, the former (and now late) president of Ghana, tweeted at the time: “The dismissal of Arikana Chihombori-Quao, AU ambassador to the United States, raises serious questions about the independence of the AU. For someone who spoke her mind about the detrimental effects of colonisation and the huge cost of French control in several parts of Africa, this is an act that can best be described as coming from French-controlled colonised minds.”

The colonised mind was also clearly on display in the case of Ouattara’s election for an illegal third term in late 2020, when he was 78. According to a report by Human Rights Watch, the security forces perpetrated the widespread violence in opposition strongholds, in league with local thugs. Here is the account of one eyewitness in the Yopougon Kouté area of Abidjan:

I saw a group coming into the neighbourhood in two Gbakas (minivans), blue taxis, and scooters. … They were armed with machetes, knives, and guns. I went out with what I could to defend my village. The neighbourhood youth started throwing stones, and there were so many of us that they fled. One of the government supporters couldn’t escape in time, and he was beaten to death by our young people.

Even as the European Union—the West—expressed “deep concerns about the tensions, provocations and incitement to hatred that have prevailed and continue to persist in the country around this election,” the AU claimed that the vote had “proceeded in a generally satisfactory manner.” But that was no surprise. As one human rights activist from Mozambique said: “the African Union is an organisation that primarily represents the interests of the powerful. It is toothless and ineffective, and it repeatedly proves itself incapable of ensuring prosperity, security, and peace for all Africans.”

In fact, the AU is not different enough from the OAU: it, too, is an old men’s club. Africa counts both some of the world’s oldest male presidents (their female counterparts are few and far between). It also counts some of the youngest demographics of any continent, and these older men jealously guard their privileges. Watch the 92-year-old Paul Biya currently planning to run in the forthcoming elections in Cameroon; he has been in power in one form or another since 1982. He isn’t even the longest-standing leader on the continent. That honour goes to the 83-year-old Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea, in power since 1979. Two decades ago, the state-operated radio station declared him “the country’s god” with “all power over men and things,” adding that he was “in permanent contact with the almighty” and “can decide to kill anyone without calling him to account and without going to hell.”

It is hardly surprising that such men would be wary of an AU that, as they see matters, is seeking to usurp their power; they are tardy in funding it. Many member states don’t bother to pay their annual contributions, which is why external sources funded two-thirds of its 2023 budget (and China built the new headquarters in Addis Ababa at its own expense). An attempt was made to rectify this anomaly in a decision adopted by the various governments at a Retreat on Financing of the Union during the 27th African Union Summit in Kigali, Rwanda, in July 2016. It directed all AU members to apply a 0.2% levy on eligible imports to finance the organisation. We are all allowed our dreams; nothing ever came of this one.

The pity of it all is that a united Africa, whose population is expected to hit 2.5 billion by 2050—and account for one in four people in the world—stands to become the most populous continent by the end of the century: it should automatically command at least one permanent seat on the UN Security Council, and with full veto power. Addressing the annual session of the UN General Assembly in 2023, Joe Biden, then the US president, seemed to make an indirect case for Africa’s inclusion at the top: “We need to be able to break the gridlock that too often stymies progress and blocks consensus on the Council. We need more voices and more perspectives at the table.” His call was repeated in 2024 by Linda Thomas-Greenfield, his Black ambassador to the UN, who waxed lyrical about being Uncle Sam’s emissary in her mother continent. Having “travelled extensively across Africa,” she said, she knew “firsthand the diversity and the talent, the depth and breadth of experience.” And so the US government would support granting the continent two permanent seats on the Security Council—but without veto power, otherwise the council would become “dysfunctional.” Chihombori-Quao rightly said that the proposal “is an insult, not only to the African leaders, but it is an insult to 1.4 billion people.” What else is new?

This article was published earlier on www.theideasletter.org and is republished under Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial-No Derivatives license.

Feature Image Credit: The Berlin Conference of 1884-5. Source: Illustrierte Zeitung via Wikimedia Commons and thecollector.com