Quick Take

IndiGo Airlines, India’s largest domestic carrier, hit a massive snag in early December 2025 with a large number of cancelled and delayed flights. The main reason was that Indigo was not ready for the strict new safety rules on how long pilots can fly, known as Flight Duty Time Limitation (FDTL), set by the aviation watchdog, the DGCA. This blunder was compounded by the fact that the airline also had 50 to 70 planes sitting idle due to technical glitches involving Pratt & Whitney engines.

The fallout was nasty: big financial hits evidenced by a decline in stock valuation and substantial refund expenditures, and a seriously bruised reputation with IndiGo’s On-Time Performance (OTP) tanking to an abysmal 19.7%, which typically exceeded 80% before the crisis. It also left a whole lot of unhappy passengers stranded across major airports, particularly during the high-demand winter period. Competitors like Air India and Akasa Air cashed in with higher prices and snatched up market share. The IndiGo crisis also placed considerable strain on the country’s overall airport infrastructure.

This whole chaos was a wake-up call, demonstrating that running a “bare-bones crew” model just doesn’t fly in the face of non-negotiable safety rules mandated by the regulators or, as in this case, the judiciary. It also underscored the role of the regulatory and judicial authorities in fundamentally shaping the operational and financial strategies of both private and public airline entities.

Why the Wheels Came Off?

The disaster was the result of new safety rules colliding with a risky strategy, particularly that of IndiGo Airlines. The new rules require the DGCA to implement the revised FDTL norms, which were intended to mitigate pilot fatigue and enhance flight safety standards.

Table 1.

| Cause Category | Specific Cause/Factor | Description |

| Regulatory Change | New FDTL Norms | The DGCA mandate necessitated an increase in the weekly pilot rest period from 36 to 48 hours, an expansion of the definition of night hours, and a severe limitation on the maximum number of night landings (from six to two per roster cycle). |

| Operational Strategy | Under-Rostering/Crew Shortage | IndiGo historically operated with a paradigm focused on high aircraft utilisation. Its standard crew buffer (estimated at approximately 4%) became effectively zero under the new regulatory framework. Pilot associations contend that this shortfall resulted from management’s “lean manpower strategy” and hiring moratoria, despite a two-year period for preparatory action. |

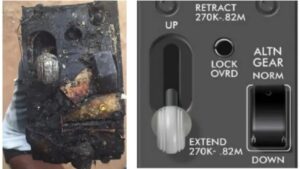

| Technical Factors | Grounded Aircraft | The airline’s capacity for operational flexibility was severely constrained by the grounding of an estimated 50–70 Airbus A320neo family aircraft. This was principally attributable to inspection requirements and component shortages related to Pratt & Whitney engines. |

| Outside Interference | Winter/Airport Traffic | Bad winter weather, minor technical issues, and already overcrowded major airports led to crew-related delays that rippled across their entire flight network, resulting in a substantial number of daily cancellations. |

Consequences

The Damage and the Industry Reaction

The consequences of the IndiGo crisis were immediate and painful, which spread across the entire aviation industry.

- Money and Image: The stock price for the parent company, InterGlobe Aviation, dropped due to higher costs and refund payments. Its image as the reliable, on-time airline was severely damaged. The company, previously lauded for its operational punctuality, faced widespread public indignation and negative media coverage over delays, inadequate communication, and poor passenger support, thereby eroding its brand equity. The widespread chaos also raised doubts among investors and passengers about the overall stability and planning skills of the Indian airline industry.

- Operations and Oversight: The disruptions instigated a massive cascading failure across the network, resulting in delayed crew rotations, aircraft being immobile at various airports, and a generalised loss of effective operational control.

- Regulatory: The DGCA stepped in with a formal investigation, putting IndiGo under the microscope.

The wider effect on the Indian aviation market was concerning as well.

Impact on Other Major Airlines in India

Given IndiGo’s dominant market position (exceeding 60% of the domestic market), its operational disruptions invariably affected the entire Indian aviation ecosystem, albeit with varying impacts.

IndiGo Versus Competitors

The differential impact of the FDTL norms as described in Table -2 highlights the varying operational strategies employed by major Indian carriers.

Table 2

| Carrier | Operational Strategy | FDTL Impact & On-Time Performance (OTP) |

| IndiGo | The Low-Cost Carrier (LCC) model focuses on high fleet utilisation, fast turnarounds, and aggressive scheduling, particularly for late-night flights. | Hit the hardest due to insufficient crew planning. OTP dropped to lows of 19.7%, significantly impacting reputation and revenue. |

| Air India/Vistara (Tata Group) | More diversified/Full-Service models; typically maintain larger pilot buffers and fewer highly aggressive night schedules compared to IndiGo’s LCC core. | While the group also lobbied against the rules, they were largely unaffected by the immediate operational meltdown. Their OTP remained relatively stable (e.g., 66.8%–67.2% during the crisis). |

| Akasa Air | Newer, agile LCC. Benefited from learning from older airlines’ mistakes and potentially scaling up its crew faster. | Maintained strong operational stability during the crisis, reporting OTPs in the range of 67.5%–73.2%. |

| SpiceJet | Legacy LCC, often facing its own financial/operational challenges. | While not immune to industry pressures, their OTP (e.g., 68.7%–82.5% range) remained significantly higher than IndiGo’s during the disruption period. |

Market and Systemic Effects of IndiGo’s Crisis

Table 3

| Airline/Sector | Impact Description | Market Effect |

| Competitors (e.g., Air India, Vistara, Akasa Air) | Temporary Market Share Gain | Passengers displaced by IndiGo’s cancellations transitioned to competing carriers, leading to a short-term increase in passenger volumes for rivals. |

| Competitors (Revenue) | Surge Pricing and Higher Yields | The sudden reduction in available network capacity from IndiGo’s cancellations allowed other airlines to implement substantial surge pricing, yielding significantly higher ticket revenue on specific routes (e.g., Delhi-Bengaluru). |

| Airport Operations | Systemic Strain | The disorder at major aviation hubs (Delhi, Pune, Mumbai, Bengaluru) was not restricted to IndiGo. Grounded IndiGo aircraft occupying parking positions impeded the movement and punctuality of all other airlines. Furthermore, passenger unrest at boarding gates disrupted the boarding processes for other flights. |

| Broader Market | Negative Sector Sentiment | Although competitors realised short-term financial gains, the extensive chaos undermined overall investor and passenger confidence regarding the stability and planning efficiency of the Indian aviation sector. |

The IndiGo crisis vividly demonstrated the fragility of a hyper-efficient, operationally lean business model when confronted by abrupt, non-negotiable regulatory shifts, particularly ordained by those prioritising aviation safety, such as the FDTL norms. While competitors accrued temporary benefits from increased fares and passenger diversion, the underlying issue underscored the necessity for long-term human resource planning across the entire industry.

Besides, ultimately, the Indian aviation sector functions under the guidelines and standards, including critical safety mandates, that the regulators like DGCA and AAI enforce, while economic regulators determine market structure and operational costs. Policies, whether judicial in origin (e.g., the High Court’s directive leading to new FDTL) or governmental (e.g., AERA tariffs and privatisation initiatives), emphasise the parameters that all airlines, public or private, must navigate to ensure safety (for the customers), viability and stability (for the industry).

The Fix: Getting Back on Track

Solving these critical issues needs both a quick patch-up and a fundamentally sound long-term strategy.

The central challenge involves addressing immediate resource constraints, specifically, the deficit of pilots due to the new FDTL norms and the incapacitation of 50–70 aircraft due to issues with Pratt & Whitney engines, while simultaneously pursuing long-term, systematic solutions to ensure sustainable expansion of the aviation sector.

Short-Term Fixes

Cut flights: IndiGo must actively reduce its flight schedule with “calibrated adjustments” to match the limited FDTL-compliant crew it actually has. The airlines should focus on reducing nighttime flights to comply with the new norms. The DGCA must formally approve the diminished schedule and enforce a strict timeline for restoration, ensuring the rebalancing measure is authentic and not a transient manoeuvre.

Temporary FDTL Exemption: On 5 December 2025, the DGCA provided IndiGo with a one-time exemption from new pilot night-duty rules and revoked a regulation that prohibited airlines from classifying pilot leave as weekly rest. However, this exemption has generated widespread apprehension, most notably from the International Federation of Air Line Pilots’ Associations (IFALPA), which states that crew fatigue “clearly affects safety.”

Fast Leasing: IndiGo need to quickly hire temporary aircraft and foreign crew through wet and damp leasing arrangements to instantly inject pilots and capacity. The DGCA must streamline the security clearance and licensing endorsement procedures for wet-leased crew and aircraft to facilitate rapid deployment

Fix the Planes: IndiGo and other affected carriers must engage in intensified collaboration with Pratt & Whitney (P&W) to expedite the delivery of spare engines and components. This necessitates aggressive follow-up, including, if necessary, diplomatic pressure on P&W’s parent company (RTX Corporation) to prioritise Indian carriers, given the magnitude of the crisis.

Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO) Push: Engine maintenance must be expedited through the utilisation of P&W’s Customer Training Centre and the India Engineering Centre (IEC) in Bengaluru. The government should provide incentives (such as the reduced GST on MRO components) to encourage domestic and international MRO centres to rapidly expand their capacity for quick engine turnarounds

Long-Term Strategy

To ensure the industry’s future growth, particularly in demand, does not precipitate a recurrence of systemic failure, the industry requires strategic, large-scale investment in both human capital and physical infrastructure.

Invest in People: All airlines must set aside resources for a mandatory 15-20% crew buffer, as is the rule now. This means saying goodbye to the “lean manpower” idea and building a required crew reserve pool to ensure compliance with the new rules and also absorb future regulatory adjustments, training demands, and natural attrition rates.

Better Training: The Indian Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) needs to incentivise the rapid expansion of local flying schools and flight simulators to keep up with the massive number of new planes ordered by various airlines and reduce the reliance on expensive foreign training.

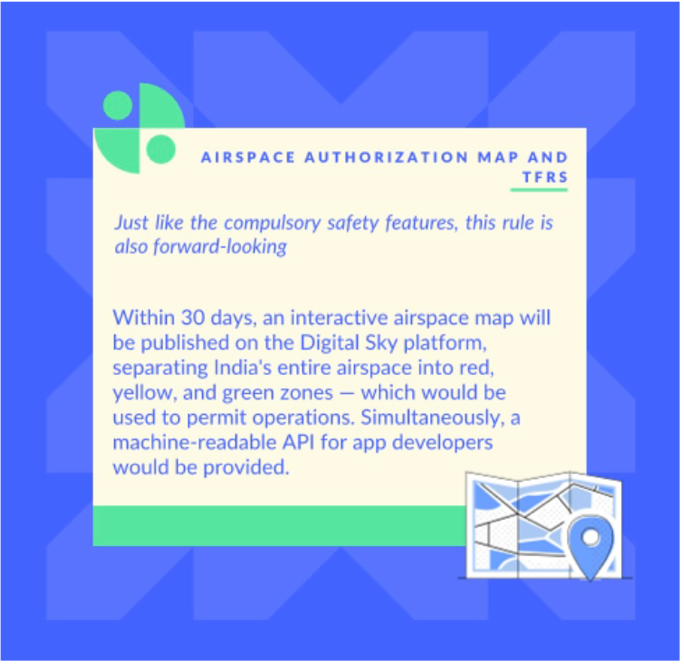

Upgrade Infrastructure: The government needs to speed up the construction of secondary airports (such as Jewar and Navi Mumbai) to take the pressure off the fully packed primary hubs. The Airports Authority of India (AAI) must invest in modern Air Traffic Management (ATM) systems to allow more planes in the airspace and reduce delays caused by weather.

Stronger Supply Chain: Airlines should think about mixing their fleets (e.g., using both Airbus and Boeing jets). The “Make in India” scheme needs to aggressively focus on building local MRO capacity for new-generation engines to reduce reliance on fragile global supply chains for crucial maintenance.

To sum up, IndiGo needs to honestly cut its schedule in the short term, with the regulators keeping a close watch on any temporary waivers. But for lasting stability, the entire Indian aviation sector must make coordinated, major investments in its human capital and physical assets to comply with the necessary regulatory and judicial mandates. The primary focus for the entire industry is safety and passenger comfort, which can’t be overemphasised.

Feature Image Credit: freepressjournal.in

Image; Indigo Chaos www.indiatoday.in