The former districts of Koraput, Balangir and Kalahandi, also known as KBK districts, were reorganised into 8 districts of Koraput, Malkangiri, Nabarangpur, Rayagada, Balangir, Subarnapur, Kalahandi and Nuapada in 1992. These districts form the South-West part of Odisha comprising the great Deccan Plateau and the Eastern Ghats. These highland districts highly rich in mineral resources, flora and fauna remain as one of the most backward regions in Odisha

Among the different forms of migration, distressed migrants remain the most impoverished and unrecognised. These migrants form the lowest strata of the society; disadvantaged by caste, poverty and structural inequalities. In Odisha, the underdeveloped region of KBK is one among the main sources of distressed migrants. They move to cities in search of employment and better wages, while in cities they are even more disadvantaged due to social, economic and linguistic barriers. Administrative and political apathy over their issues has only enhanced their distress.

This paper attempts to address three questions:

- What are the characteristics of distressed migrants in KBK district, Odisha?

- What are the existing policies of the state to curb this form of migration?

- What form of government intervention is required to address this distress?

The analysis is carried out through a review of published articles, government reports, e-books and newspaper reports.

Defining distress migration

Migration is a multifaceted concept driven by diverse factors. Migration can be internal or international, voluntary or involuntary, temporary or permanent. Depending on the pattern and choice of migration, each migratory trend could be characterised into different forms. Distress migration is one such form of migration.

Involuntary migration is often associated with displacement out of conflict, environmental distress, climatic change etc. That is any sudden threat or event forces people to migrate. However, involuntary migration may also arise out of socio-economic factors such as poverty, food insecurity, lack of employment opportunities, unequal distribution of resources etc. This component of involuntary migration is addressed by the concept of distress migration (Avis, 2017).

To understand distressed rural-urban migration in India, the broad definition used by Mander and Sahgal (2010) in their analysis of rural-urban migration in Delhi can be employed. They have discussed distress migration as:

“Such movement from one’s usual place of residence which is undertaken in conditions where the individual and/or the family perceive that there are no options open to them to survive with dignity, except to migrate. Such distress is usually associated with extreme paucity of alternate economic options, and natural calamities such as floods and drought. But there may also be acute forms of social distress which also spur migration, such as fear of violence and discrimination which is embedded in patriarchy, caste discrimination, and ethnic and religious communal violence” ( Mander and Sahgal, 2010)

In brief, the definition states that distress migration is caused by an array of issues. Environmental disasters, economic deprivation, gender or social oppression, lack of alternate employment opportunities and inability to survive with dignity are mentioned as the main drivers of distress migration (Avis, 2017).

Thus, distress migration is a form of temporary migration driven by environmental and socio-economic factors and not based on an informed or voluntary choice.

Profile of KBK districts

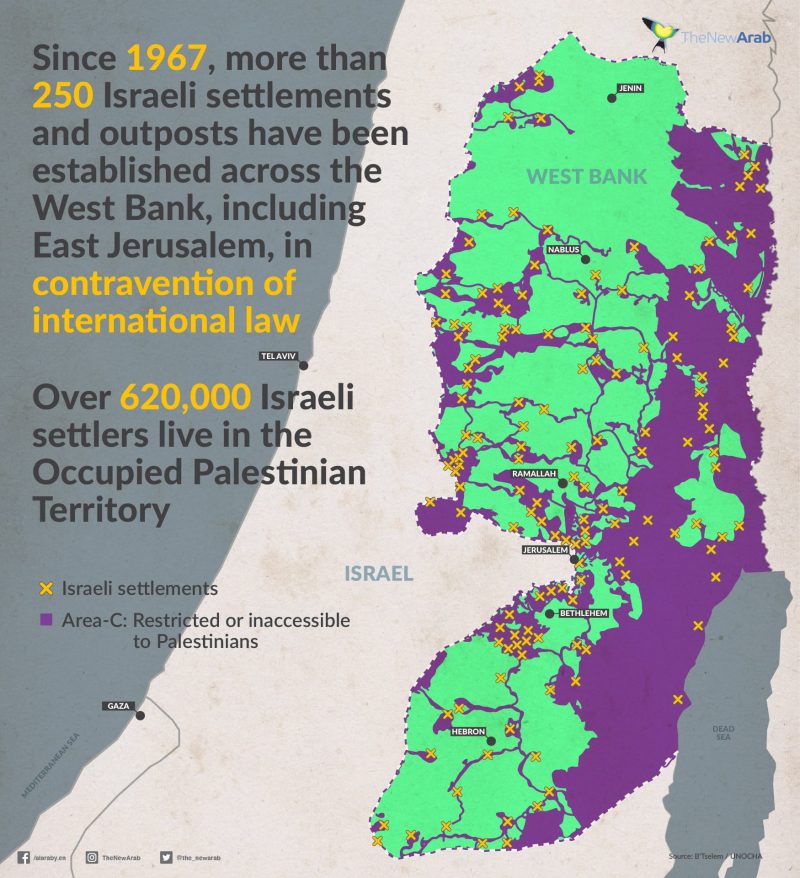

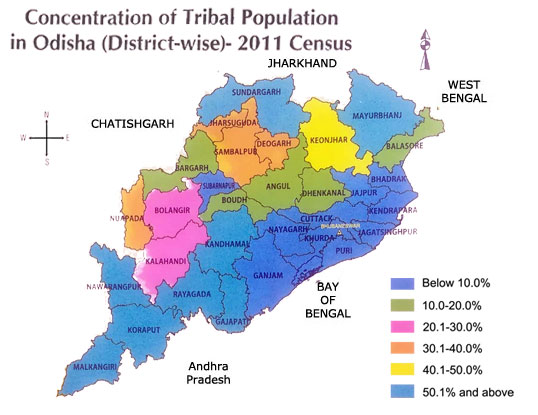

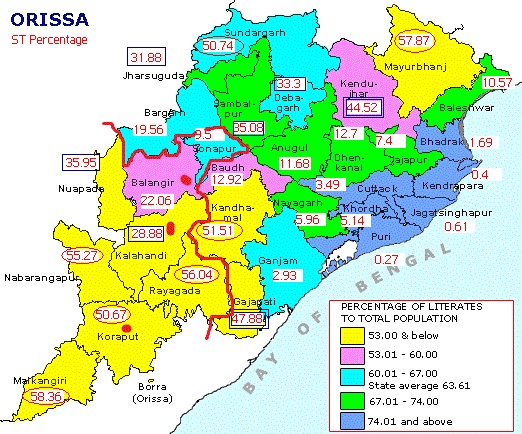

The former districts of Koraput, Balangir and Kalahandi, also known as the KBK districts, were reorganised into 8 districts of Koraput, Malkangiri, Nabarangpur, Rayagada, Balangir, Subarnapur, Kalahandi and Nuapada in 1992. These districts form the South-West part of Odisha comprising the great Deccan Plateau and the Eastern Ghats. These highland districts highly rich in mineral resources, flora and fauna remain as one of the most backward regions in Odisha. The region is termed backward on account of rural backwardness, high poverty rates, low literacy rates, underdeveloped agriculture and poor development of infrastructure and transportation (Directorate of Economics and Statistics, 2021).

The districts are home to primitive tribal communities such as Gonds, Koyas, Kotias etc. dependent on forest produce and subsistence agriculture for a living. KBK region registered a workforce participation rate of 48.06 % in the 2011 census. There was a significant occupation change noticed from the 2011 census. The region witnessed a fall in cultivators from 33% in 2001 to 26.7% in 2011. However, the fall in cultivators was compensated with an increase in agricultural labourers from 44.24 % in 2001 to 48.87% in 2011. Employment in household industries also witnessed a downfall between the period of 2001 to 2011 (Sethy, 2020).

The rise in agricultural labourers has a negative impact on the communities. As agriculture is underdeveloped owing to the arid nature of the region, crop failure, extreme calamities, low net irrigated area and falling government expenditure, these workers are pushed into abject poverty. In search of alternate employment options, these workers migrate to other areas of employment in rural or urban pockets. Such a form of seasonal migration during the lean period in agriculture is a predominant phenomenon in these districts. Their dependence on non-timber forest produce is hindered by the rapid deterioration and deforestation of forests for development projects and mining.

Characteristics of distressed migrants in KBK region

- Who Are These Distressed Migrants?

In the KBK region, distress migration has been a popular coping strategy during lean periods of agriculture. And this strategy is majorly adapted by disadvantaged and marginalised sections of the region. They are disadvantaged by caste, chronic poverty, landlessness, low levels of literacy and skills, increased dependence on forest and agriculture and debt-ridden (Meher, 2017; Mishra D.K., 2011; Tripathy, 2015, 2021).

- Why Do They Migrate

Distressed migration in the region is induced by many interlinked factors. One such factor is that the region is highly under-developed in terms of social and economic infrastructure. Such under-development puts the communities at a disadvantage with low levels of literacy and skills. Their dependence on agriculture and forest produce for livelihood rises. However, agriculture is under-developed and forests are subjected to high levels of deforestation. With low levels of income, crop failure and non-availability of alternate employment opportunities, the communities are subjected to absolute levels of poverty, food and employment insecurities (Kujur, 2019).

Landlessness is also identified as one significant push factor. As the region is highly dominated by tribal communities, they are more attached to and dependent on the forest cover. Globalisation and industrialisation resulted in deforestation and encroachment of farmlands for industrial and mining purposes. Eventually, a major proportion of land remains with a smaller group of wealthy people (Mishra D.K., 2011). Relocation and involuntary displacement also result in the loss of their livelihood that is dependent on the local environment (Jaysawal & Saha, 2016).

With falling income, people approach local moneylenders to meet their basic sustenance needs. With low incomes from agriculture and forest produce, families approach these informal creditors to meet emergency needs like marriage, birth and death rituals or medical treatment as well as to meet basic consumption needs with the expectation of cash flow from labour contractors during the lean season. Moneylenders exploit them by charging higher interest rates. Thus, the non-availability of formal credit facilities pushes them into a debt trap and further to adopt migration (KARMI, 2014; Mishra D.K., 2016).

The region is also subject to extreme calamities and drought. Small and marginal farmers, poor in income and land, choose to migrate as they are unable to cope with the regular droughts and climate change. A study on historical analysis of the effect of climate on migration in Western Odisha mentions that the migratory trend saw a rise after the mega drought in 1965. Up until then, large-scale migration from the region was not a phenomenon (Panda, 2017).

- Channel of Migration

Sardars provide an advance amount and in exchange, the debtor or any family member agrees to work for them for a stipulated period, usually six months. Hence, there exists a form of debt bondage. Large-scale family migration through this system is seen in the KBK region. The major stream of such bonded labour migration is witnessed towards brick kilns in Andhra Pradesh

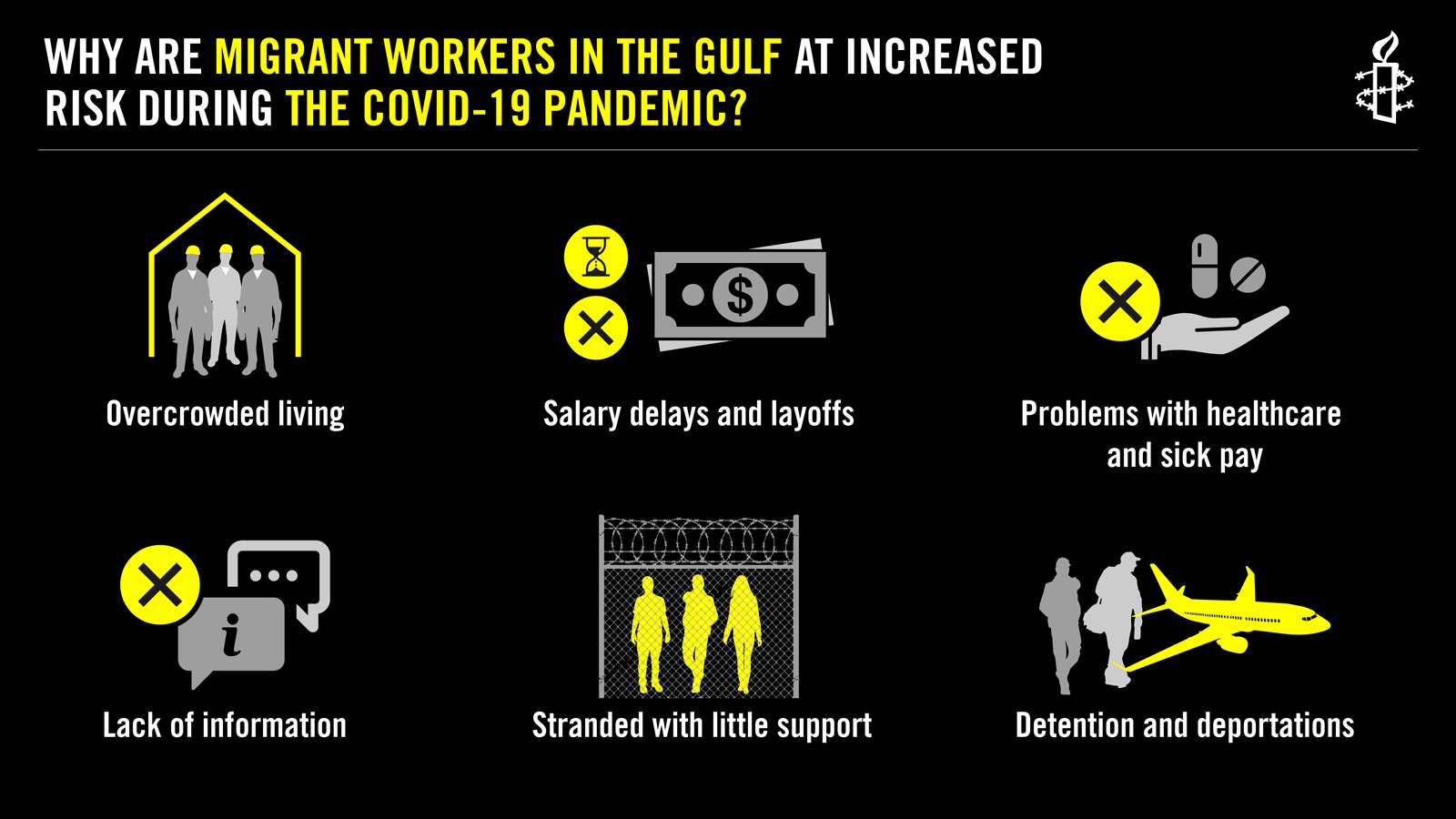

In the region, seasonal migration occurs through the channels of agents, locally known as Sardars, on a contractual basis. This form of migration is known as Dadan labour migration. The poor migrant labourers are known as Dadan and they are recruited by Sardars, who are usually local people who are familiar with residents in the region (KARMI, 2014). During the period of Nukhai, they go around the villages and contact prospective labourers. These Sardars are the intermediary between the employer and the migrant labourer. Sardars provide an advance amount and in exchange, the debtor or any family member agrees to work for them for a stipulated period, usually six months. Hence, there exists a form of debt bondage. Large-scale family migration through this system is seen in the KBK region. The major stream of such bonded labour migration is witnessed towards brick kilns in Andhra Pradesh. They are also a major source of labour in the areas of construction, handlooms and other forms of informal sector work across South India (Daniels, 2014). The problems they face in the destination are manifold. They are subjected to poor working conditions, poor housing and sanitation facilities and limited access to education and health facilities. They are recognised as cheap labour with limited bargaining power owing to their social, cultural and linguistic exclusion in the destination state. Upon entering the contract their freedom to move and freedom to express is denied (Acharya, 2020).

- Pull Factors to Migrate

The hope of availability of better job opportunities and wages is the main pull factor. However, upon the analysis of the nature of migration, push factors have a higher weightage in inducing such distress migration. Migration to brick kilns and other informal sectors from the KBK region can be termed as distress migration as in this case, distress is caused mainly by socioeconomic factors. It is not an informed or voluntary choice. Debt migration remains the only coping strategy that they could adopt.

Government intervention to curb such distress

- Policies Addressing Debt-Bondage Migration:

The first attempt of the state government to address Dadan migration or debt migration is the enactment of the Dadan Labour (Control and Regulation) Act (ORLA) in 1975. The act had provisions for the registration of labourers and agents, ensuring compliance of minimum wages and favourable working conditions and appointing inspection officers and dispute redressal committees (Daniels, 2014). However, the act remained on paper and no evidence of enactment was published until it was repealed in 1979 upon the enactment of the Interstate Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979 (Nanda, 2017).

The ISMW act has been criticised to be inadequate and failing to regulate and facilitate safe migration. According to the act, only those interstate migrant workmen who are recruited by licensed agents come under the ambit of the act. However, most agents involved in Dadan migration are not licensed and hence, these workers cannot avail of any of the provisions of the act (Singh, 2020). Though registration of labour contractors is mandatory in the origin state, there is no information about the names of these contractors and hence, further monitoring of the migration process is avoided (NCABL, 2016). Lack of adequate enforcement, under-staffing and poor infrastructure are identified as the reasons for poor implementation of the act in the state (Daniels, 2014).

A positive attempt against distress migration was the Memorandum of Undertaking (MoU) initiated between the labour department of Odisha and Andhra Pradesh to ensure labour welfare measures of migrant workers in Brick Kilns. After the MoU, the state of undivided Andhra Pradesh took up various progressive measures in education, health, housing and PDS for migrant workers in Brick Kilns. ILO necessitated the need for states to enter into inter-state MoUs to effectively address the bonded labour migration. However, no further MoU was signed with other states like Tamil Nadu, Chhattisgarh etc. which are also among the major host states for migrants from the region (NCABL, 2016).

The Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act enacted in 1976 governs the provisions for identification, rescue and rehabilitation of bonded labourers across the country. The act has its loopholes in implementation. There is no information on whether vigilance committees have been set up in every district or whether the surveys have been periodically conducted or to what extent the act has been functioning in the state (Post News Network, 2019). The centrally sponsored scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labour also has its setbacks. There have been reported cases of delay and denial of financial aid by district officials ( Mishra .S., 2016). In 2016, with restructuring and revamping of the Rehabilitation scheme, rescued workers could only avail the full amount of financial aid with the prosecution of the accused employers. With no database on the employer, the rates of prosecution have been low and the rescued bonded labour do not receive their funds (NACBL, 2016)

- Ensuring Accessibility of Health Facilities in Destination

The Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana or RSBY launched by the central government in 2008 provides health insurance to BPL families. The scheme incorporates provisions to split smart cards so those migrant workers could avail health insurance in destination states. After signing of the MoU between Andhra Pradesh and Odisha, the two states took steps to spreading awareness among the migrant workers about how to use the smart cards (Inter-State Migrant Workman Act (ISMW), Labour Directorate, n.d.)

- Ensuring Education of Migrant Workers Children

The state of Odisha has established seasonal hostels to ensure the education of children of migrant workers. The children are enrolled in seasonal hostels during October-June, that is until their parents return home (Odisha Primary Education Programme Authority, n.d.). The state has ensured the education of migrant children at their destination state by sending Odiya textbooks and Odiya teachers to residential schools in Andhra Pradesh (Inter-State Migrant Workman Act (ISMW), Labour Directorate, n.d.).

- Alternate Employment Opportunities: MGNREGA

Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) was introduced in 2006 to provide guaranteed employment to rural poor with the objective of uplifting them from poverty and restricting distress migration. A study analysing the performance of MGNREGA through secondary sources of data suggests that based on physical criteria of 100 Days of Wage Employment, Person-days generated, ST and Women person-days and financial performance in terms of total expenditure, total wages, average cost and average wage rate per day person, the performance of MGNREGA in KBK districts is better compared to Non- KBK districts. But the region is lagging in rural employability criteria based on average days of employment provided per household and job cards issued (Sahoo et al., 2018). Labour in the region is not interested to work under MGNREGA due to its dismal implementation in the state. Workers complain about the delay in receiving payments and instances of the creation of non-existent workers’ names among MGNREGA’s beneficiaries (KARMI, 2014). Uncertain and low wages make these labourers favour migration to Brick Kilns in hope of better wages (Deep, 2018).

- Development Policies in KBK Region

The KBK region has a high incidence of poverty owing to regional disparities in development and social exclusion based on caste. The main initiatives implemented by the state government for the upliftment of the KBK region are the Special Area Development Programme, Revised Long Term Action Plan (RLTAP), Biju KBK Plan, Backward Regions Grants Fund, Gopabandhu Gramin Yojana (GGY), Special Central Assistance (SCA) for tribal sub-plan (TSP) areas, Western Odisha Development Council (WODC) and Grants under Article 275(1) of the Constitution. Development projects to reduce poverty and regional disparities are obstructed by economic, social and institutional factors (Mishra, 2020).

The state of Odisha has done positive interventions in the education of migrant children and health facilities of the migrant population. However, the distress migration is still prevalent owing to the social and economic exclusion and debt bondage situations in the region. Land grabbing in the name of development left the tribal communities poor and in distress. Structural inequalities induced by caste discrimination are enhanced with such landlessness.

Policy Recommendations

The state of Odisha has done positive interventions in the education of migrant children and health facilities of the migrant population. However, the distress migration is still prevalent owing to the social and economic exclusion and debt bondage situations in the region. Several initiatives and schemes have been enacted to address distress migration; however, their failure in reducing distress can be linked to dismal governance, poor implementation and misappropriation of schemes.

The state must ensure migration to be safe and a viable coping strategy. From this study it is suggested the state of Odisha follow a multipronged approach to address the distress.

Origin state (Odisha) interventions

- Short Term Interventions:

- The system of debt bondage should be completely abolished by the proper implementation of legislation. Different loopholes in implementation such as the delay in the release of funds, prosecution of accused and identification and registration of middlemen should be addressed. Apart from the financial aid, the state should intervene in providing a comprehensive livelihood plan for the rescued labourers. Abolishing the bonded labour system is essential to reduce distress and make migration safe.

- Informal sources of credit should be eliminated and formal credit and microfinance facilities should be made available. Such facilities would reduce the exploitation and prevent the creation of absurd debt. Formal credit provides opportunities for small and marginal farmers to indulge in productive investments. This enables them to cope with extreme climatic changes.

- Land grabbing in the name of development left the tribal communities poor and in distress. Structural inequalities induced by caste discrimination are enhanced with such landlessness. The provision of land ownership enables the communities to enjoy land-based benefits which further supports them to sustain their livelihood. Ownership of land also provides the indigenous community with a sense of social and economic significance.

- Long term interventions

- The state should engage in enhancing the skills of the people in the region. Vocational skill training and development schemes can be introduced. This could expand the opportunities available for employment and distribute labour across all the economic sectors.

- Rural development should be given higher priority. The state of Odisha has already initiated many schemes for the development of the KBK region. However, the state should study the economic and social factors that stagnate the process of development in the region. Chronic poverty, poor infrastructural and rural connectivity and dismal education and health facilities are some of the important areas that require attention.

Host state intervention

- The host state needs to create a database of migrants entering their state. A statistically significant database on migrants solves a huge array of issues faced by the migrant in the destination state. A comprehensive database helps in identifying and recognising migrants. It also allows for understanding the different characteristics of migrants and the sectors in which they are employed. This would be beneficial for monitoring and ensuring safe and favourable working conditions. A database also helps in ensuring the availability and accessibility of social security and entitlements in host states.

- Migrant labour is as important to the destination state as it is to the origin state. Both origin and host state should cooperate towards making migration a viable livelihood strategy.

Another important area where both the origin and host state should intervene together is creating awareness among workers about the existing provisions and rights available to them. Access to the same should be made easy.

Conclusion

The highly backward districts of the KBK region remain a major source of distressed migrants. Years of state initiative in reducing distress have had negligible impact. The area remains underdeveloped and migration is the only viable choice of employment. Migration can only be a viable coping strategy for seasonal migrants when the channel of migration is made legal and safe. The major drawback in any initiative attempted to resolve distress is the poor implementation. Administrative apathy, corruption and misappropriation of schemes have stagnated the progress of every initiative.

References

- Acharya, A. K. (2020). Caste-based migration and exposure to abuse and exploitation: Dadan labour migration in India. Contemporary Social Science, 1-13.

- Avis, W. R. (2017). Scoping study on defining and measuring distress migration.

- Bhatta Mishra, R. (2020). Distress migration and employment in indigenous Odisha, India: Evidence from migrant-sending households. World Development, 136, 105047.

- Daniels, U. (2014). Analytical review of the market, state and civil society response to seasonal migration from Odisha. Studies, stories and a canvas seasonal labour migration and migrant workers from Odisha, 106-115.

- Deep, S. S. Seasonal Migration and Exclusion: Educational Experiences of children in Brick Kilns. Ideas, Peoples and Inclusive Education in India. National Coalition for Education, India. 2018.

- Directorate of Economics and Statistics (2021). Odisha Economic Survey 2020-21. Planning and Convergence Department. Government of Odisha. http://www.desOdisha.nic.in/pdf/Odisha%20Economic%20Survey%202020-21-1.pdf

- Giri, J. (2009). Migration in Koraput: “In Search of a Less Grim Set of Possibilities” A Study in Four Blocks of tribal-dominated Koraput District, Odisha. Society for Promoting Rural Education and Development, Odisha, 1.

- Inter-State Migrant Workman Act (ISMW) | Labour Directorate. (n.d.). Labour Directorate, Government of Odisha. Retrieved August 10, 2021, from https://labdirodisha.gov.in/?q=node/63%27%3B.

- Jaysawal, N., & Saha, S. (2018). Impact of displacement on livelihood: a case study of Odisha. Community Development Journal, 53(1), 136-154.j

- Jena, M. (2018, July 21). Distress migration: land ownership can put a break. The Pioneer. https://www.dailypioneer.com/2018/state-editions/distress-migration-land-ownership-can-put-a-break.html

- KARMI. (2014). Migration Study Report of Golamunda Block of Kalahandi District of Odisha. Pp.13. Kalahandi Organisation of AgKriculture and Rural Marketing Initiative (KARMI), Kalahandi Odisha.

- Kujur, R. (2019). Underdevelopment and patterns of labour migration: a reflection from Bolangir district, Odisha. research journal of social sciences, 10(1).

- Mahapatra, S. K., & Patra, C. (2020). Effect of migration on agricultural growth & development of KBK District of Odisha: A statistical assessment. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, Sp, 9(2), 162-167.

- Mander, H., & Sahgal, G. (2010). Internal migration in India: distress and opportunities, a study of internal migrants to vulnerable occupations in Delhi.

- Meher, S. K. (2017). Distress seasonal migration in rural Odisha A case study of Nuapada District.

- Mishra, D. K. (2011, April). Behind dispossession: State, land grabbing and agrarian change in rural Odisha. In International conference on global land grabbing(Vol. 6, No. 8).

- Mishra, D. K. (2016). Seasonal migration from Odisha: a view from the field. Internal migration in contemporary India, 263-290.

- Mishra, S. (2016, January 13). Rescued migrant workers get raw deal from Govt. The Pioneer. https://www.dailypioneer.com/2016/state-editions/rescued-migrant-workers-get-raw-deal-from-govt.html

- Mishra, S. (2020). Regional Disparities in Odisha–A Study of the Undivided “Kbk” Districts. Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 11(4), 261-266.

- Nanda, S. K. (2017). Labour scenario in Odisha. Odisha Review, 73(10), 20-25.

- NCABL. (2016). Joint Stakeholders’ Report on Situation of Bonded Labour in India for Submission to United Nations Universal Periodic Review III. NATIONAL COALITION FOR ABOLITION OF BONDED LABOUR (NCABL), Bhubaneswar Odisha.

- Panda, A. (2017). Climate change, drought and vulnerability: A historical narrative approach to migration from Western Odisha, India. In Climate Change, Vulnerability and Migration(pp. 193-211). Routledge India.

- Post News Network. (2019, April 30). Elimination of bonded labour calls for cohesive action plan. Odisha News, Odisha Latest News, Odisha Daily – OdishaPOST. https://www.Odishapost.com/elimination-of-bonded-labour-calls-for-cohesive-action-plan/

- Sahoo, M., Pradhan, L., & Mishra, S. (2018). MGNREGA and Labour Employability-A Comparative Analysis of KBK and Non-KBK Regions of Odisha, India. Indian Journal of Economics and Development, 6(9), 1-8.

- Sethy, P. (2020). Changing Occupational Structure of Workers in KBK Districts of Odisha. Center for Development Economic, 6(06), 17-28.

- Singh, V. K. (2020, April 22). Opinion | The ‘nowhere people’ of COVID-19 need better legal safeguards. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/the-nowhere-people-of-covid-19-need-better-legal-safeguards/article31400344.ece

- Tripathy, S. N. (2015). Evaluating the role of micro-finance in mitigating the problems of distress out-migrants: A study in KBK districts of Odisha. The Micro Finance Review, Journal of the Centre for Micro Finance Research.

- Tripathy, S. N. (2021). Distress Migration Among Ultra-poor Households in Western Odisha. Journal of Land and Rural Studies, 23210249211001975.

Feature Image: Tata Trusts

TPF Occasional Paper

TPF Occasional Paper