[powerkit_button size=”lg” style=”info” block=”true” url=”https://admin.thepeninsula.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Clausewitz-and-Sun-Tzu-1.pdf” target=”_blank” nofollow=”false”]

Download

[/powerkit_button]

“No principle in the world is always right, and no thing is always wrong. What was used yesterday may be rejected today, what is rejected now may be used later on. This use or disuse has no fixed right or wrong. To avail yourself of opportunities at just the right time, responding to events without being set in your ways is in the domain of wisdom. If your wisdom is insufficient (…) you’lle come to an impasse wherever you go.”

– Taostic Text

Every war has its own strategy and also its own theorist. In fact, there are only two great theorists of war and warfare, the Prussian “philosopher of war” Carl von Clausewitz, and the ancient Chinese theorist of the “art of war”, Sun Tzu. Nevertheless, there is no single strategy that applies equally to all cases, i.e., not even Clausewitz’s or Sun Tzu’s. Often an explanation for success or failure is sought in the strategies used only in retrospect. For example, Harry G. Summers (Summers 1982) attributed the defeat of the United States in the Vietnam War to the failure to take into account the unity of people, army, and government, Clausewitz’s “wondrous trinity.” In contrast, after the successful campaign against Iraq in 1991, the then Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, Colin Powell, appeared before the press with Clausewitz’s Book of War and signaled, see, we learned from the mistakes of the Vietnam War and won the Iraq War with Clausewitz (Herberg-Rothe 2007). Similarly, after World War I, there was a discourse that amounted to if the German generals had read Clausewitz correctly, the war would not have been lost. This position referred to the victory of the German forces in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and the assessment of the then Chief of General Staff, Helmut von Moltke, that he was able to fight this war successfully by studying Clausewitz’s “On War.” Since then, Clausewitz’s book has been searched for reasons for victory or defeat (Herberg-Rothe 2007).

If Clausewitz’s status seemed unchallenged after the Iraq war in 1991, it was gradually questioned and often replaced by Sun Tzu. Two reasons played a role here – on the one hand, the new forms of non-state violence and, on the other, the new technological possibilities, the revolution in military affais (RMA), which is far from being completed. In particular, robotic and hybrid warfare, as well as the incorporation of artificial intelligence, that of space, and the development of quantum computers. The trigger of the change from Clausewitz to Sun Tzu was a seemingly new form of war, the so-called “New Wars”, which in the strict sense were not new at all, but are civil wars or those of non-state groups. In the view of the epoch-making theorist of the “New Wars”, Mary Kaldor (Kaldor 2000, much more differentiated Münkler 2002), interstate war was replaced by non-state wars, which were characterized by special cruelty of the belligerents. These weapon bearers, seemingly a return to the past, were symbolized by child soldiers, warlords, drug barons, archaic fighters, terrorists, and common criminals who were stylized as freedom fighters (Herberg-Rothe 2017).

Since Sun Tzu lived in a time of perpetual civil wars in China, his “art of war” seemed more applicable to intrastate war, (McNeilley 2001) while Clausewitz’s conception was attributed to interstate war. In combating these new weapons carriers and the “markets of violence,” civil war economies, or “spaces open to violence” associated with them, Napoleon’s guiding principle was applied: “Only partisans help against partisans” (Herberg-Rothe 2017). Accordingly, conceptions of warfare were developed by John Keegan and Martin van Creveld, for example, that amounted to an archaic warrior with state-of-the-art technologies (Keegan 1995, van Creveld 1991). On the military level, the transformation of parts of the Western armed forces as well as the Bundeswehr from a defensive army to an intervention army took place. In contrast to the United States, the Bundeswehr placed greater emphasis on pacifying civil society in these civil war economies, and ideally the soldier became a social worker in uniform (Bredow 2006).

The battle was fought by highly professional special forces in complex conflict areas. The initial success of the U.S. Army in Afghanistan can be attributed to the use of such special forces, which, as a result of modern communications capabilities, were able to engage superior U.S. airpower at any time. Because interstate warfare has returned to the forefront with the Ukraine war, Clausewitz may regain relevance in the coming years – unless the controversial concepts of hybrid warfare, John Boyd’s OODA loop, or NATO’s comprehensive approach gain further influence. At their core, these are based on non-state warfare by states, thus enabling a renaissance of Sun Tzu.

However, the paradigm shift from Clausewitz to Sun Tzu became even clearer during the Second Iraq war in 2003. From the perspective of one commentator, this campaign was won in just a few weeks because the U.S. army was guided by Sun Tzu’s principles, while Saddam Hussein’s Russian advisors adhered to Clausewitz and Moscow’s defense against Napoleon (Macan 2003/Peters 2003). Before the fall of Afghanistan, former U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis brought up the Clausewitz/Sun Tzu distinction anew. “The Army was always big on Clausewitz, the Prussian; the Navy on Alfred Thayer Mahan, the American; and the Air Force on Giulio Douhet, the Italian. But the Marine Corps has always been more Eastern-oriented. I am much more comfortable with Sun-Tzu and his approach to warfare.” (Mattis 2008).

Without fully following this distinction, it gives us hints that we cannot find absolutely valid approaches in Clausewitz’s and Sun Tzu’s conceptions, but differentiations in warfare. If we simplify the difference between the two, Clausewitz’s approach is more comparable to wrestling (Clausewitz 1991, 191), while Sun Tzu’s is comparable to jiu-jitsu. The difference between the two becomes even clearer when comparing Clausewitz’s conception to a boxing match. The goal is to render the opponent incapable of fighting (Clausewitz 1991, 191) by striking his body, as Clausewitz himself points out, thereby forcing him to make any peace. In contrast, Sun Tzu’s goal is to unbalance his opponent so that even a light blow will force him to the ground because he will be brought down by his own efforts. Of course, all two aspects play a major role in both Clausewitz and Sun Tzu, but Clausewitz’s strategy relates more to the body, the material means available to the war opponents, Sun Tzu’s strategy more to the mind, the will to fight. Both strategies have also often been conceptualized as the antithesis of direct and indirect strategy – in direct strategy, two more or less similar opponents fight on a delineated battlefield with roughly equal weapons and “measure their strength” – in indirect strategy, on the other hand, attempts are made, for example, to disrupt the enemy’s supply of food and weapons or to break the will of the opposing population to continue supporting the war. Examples of this in World War II would be the tank battles for symmetric and the bombing of German cities and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as an example of asymmetric warfare. Non-state warfare is also asymmetrically structured in nearly all cases, as it is primarily directed against the enemy civilian population (Wassermann 2015). Perhaps asymmetric warfare was most evident in the Yom Kippur War between Israel and the Egyptian army. The latter had indeed surprised Israel and managed to overrun Israeli positions along the Suez Canal. However, instead of giving the Egyptian army a tank battle in the Sinai, a relatively small group of tanks set back across the Suez Canal and in the back of the Egyptian army, cutting it off from the water supply, forcing the Egyptian army to surrender within a few days (Herberg-Rothe 2017).

This distinction between Clausewitz and Sun Tzu can be contradicted insofar as Clausewitz begins with a “definition” of war in which the will plays a major role and which states that war is an act of violence to force the opponent to fulfill our will (Clausewitz 1991, 191). But how is the opponent forced to do this in Clausewitz’s conception? A few pages further on it says by destroying the opponent’s forces. By this concept of annihilation, however, he does not understand physical destruction in the narrower sense, but to put the armed forces of the opponent in such a state that they can no longer continue the fight (Clausewitz 1991 215).

Sun Tzu

Sun Tzu’s approach relates more directly to the enemy’s thinking. “The greatest achievement is to break the enemy’s resistance without a fight” (Sunzi 1988, 35). Accordingly, Basil Liddell Hart later formulated, “Paralyzing the enemy’s nervous system is a more economical form of operation than blows to the enemy’s body.” (Liddel Hart, 281). Sun Tzu’s methodical thinking aims at a dispassionate assessment of the strategic situation and thus at achieving inner distance from events as a form of objectivity. This approach is rooted in Taoism, and in it the presentation of paradoxes is elevated to a method. Although the “Art of War” contains a number of seemingly unambiguous doctrines and rules of thumb, they cannot be combined into a consistent body of thought.

In this way, Sun Tsu confronts his readers (who are also his students) with thinking tasks that must be solved. Often these tasks take the form of the paradoxical. This becomes quite obvious in the following central paradox: “To fight and win in all your battles is not the greatest achievement. The greatest achievement is to break the enemy’s resistance without a fight.”(Sun Tzu). In clear contradiction to the rest of the book, which deals with warfare, Sun Tsu here formulates the ideal of victory without a battle and thus comes very close to the ideal of hybrid warfare, in which possible battle is only one of several options.

Obviously, he wants to urge his readers to carefully consider whether a war should be waged and, if so, under what conditions. It is consistent with this that Sun Tsu repeatedly reflects on the economy of war, on its economic and social costs, and at the same time refers to the less expensive means of warfare: cunning, deception, forgery, and spies. Victory without combat is thus the paradox with which Sun Tsu seeks to minimize the costs of an unavoidable conflict, limit senseless violence and destruction, and point to the unintended effects.

The form of the paradox is used several times in the book, for example when Sun Tsu recommends performing deceptive maneuvers whenever possible; this contradicts his statement that information about the opponent can be obtained accurately and used effectively – at least when the opponent is also skilled in deceptive maneuvers or is also able to see through the deceptions of his opponent. This contradiction stands out particularly glaringly when one considers that Sun Tsu repeatedly emphasizes the importance of knowledge, for example when he says: “If you know the enemy and yourself, there is no doubt about your victory; if you know heaven and earth, then your victory will be complete” (Sunzi 1988, 211). In a situation in which one must assume that the other person also strives to know as much as possible, this sentence can only be understood as a normative demand, as an ideal: Knowledge becomes power when it represents a knowledge advantage, as Michel Foucault has emphasized in more recent times: For him, knowledge is power. Cunning, deception, and the flow of information, even when they are not absolutely necessary, are, however, in danger of becoming ends in themselves, because they alone guarantee an advantage in knowledge. Information, then, is the gold and oil of the 21st century.

The presentation of paradoxes is not an inadequacy for Sun Tsu, but the procedure by which he instructs his readers/students. In contrast to the theoretical designs of many Western schools, Sun Tsu relies here on non-directive learning: the paradox demands active participation from the reader, mirrors to him his structure of thinking, and makes him question the suitability of his own point of view in thinking through the position of the opponent. Sun Tsu thereby forces his recipients to constantly examine the current situation and to frequently reflect. By repetitively thinking through paradoxical contradictions, the actor gains the inner distance and detachment from the conflict that are necessary for an impersonal, objectifying view of events. By being confronted with paradoxes, the reader learns to simultaneously adopt very different points of view, to play through the given variants, to form an understanding for the contradictions of real situations, and at the same time to make decisions as rationally as possible. In this way, the text encourages people not to rely on the doctrines it formulates as positive knowledge about conflict strategies, but to practice repeated and ever new thinking through as a method. Sun Tzu’s approach is thus characterized by highlighting paradoxes of warfare by designing strategies of action through reflection aimed at influencing the thinking of the opponent.

Elective Affinities with Mao Tse-tung

The conception of the “people’s war” by the Chinese revolutionary Mao Tse-Tung is a further development of that of Sun Tzu and the dialectical thinking of Marx and Engels. At the same time, in these paradoxes, he tries to provide an assessment and analysis of the situation that is as objective-scientific as possible, linking it to subjective experience: “Therefore, the objects of study and cognition include both the enemy’s situation and our own situation, these two sides must be considered as objects of investigation, while only our brain (thought) is the investigating object” (Mao 1970, 26).

The comprehensive analyses that Mao prefaces each of his treatises have two purposes: On the one hand, they serve as sober, objective investigations before and during the clashes, which are intended to ensure rational predictions of what will happen and are based on reliable information and the most precise planning. On the other hand, Mao uses them to achieve the highest level of persuasion and to mobilize his followers through politicization. Not for nothing are terms like “explain,” “persuade,” “discuss,” and “convince” constantly repeated in his writings, since the people’s war he propagates requires unconditional loyalty and high morale.

Mao repeatedly demonstrates thinking in interdependent opposites, which can be understood as a military adaptation of the Chinese concept of Yin and Yang. His precise analyses demonstrate dialectical reversals; thus he can show that in strength is hidden weakness and in weakness is hidden strength. According to this thinking, in every disadvantage an advantage can be found, and in every disadvantage an advantage. An example of this is his explanation of the dispersion of forces: while conventional strategies proclaim the concentration of forces (as does Clausewitz, Clausewitz 1991, 468), Mao relies on dispersion. This approach confuses the opponent and creates the illusion of the omnipresence of his opponent.

Mao understands confrontations as reciprocal interactions and, from this perspective, is able to weigh the relationship between concentration and dispersion differently: “Performing a mock maneuver in the East, but undertaking the attack in the West” (Mao 1970, 372) means to bind the attention of the opponent, but at the same time to become active where the opponent least expects it. Mao’s method of dialectically seeking out weakness in strength and strength in weakness leads him to the flexibility that is indispensable for confronting a stronger opponent.

Finally, it is the ruthless analysis of one’s own mistakes that bring Mao to his guiding principles; from a series of sensitive defeats, he concluded, “The aim of war consists in nothing other than ‘self-preservation and the destruction of the enemy’ (to destroy the enemy means to disarm him or ‘deprive him of his power of resistance,’ but not to physically destroy him to the last man)” (Mao 1970, 349). On this point, Mao Tse Tung is in complete agreement with Clausewitz. Mao also clarifies this core proposition by defining the concept of self-preservation dialectically – namely, as an amalgamation of opposites: “Sacrifice and self-preservation are opposites that condition each other. For such sacrifices are not only necessary in order to preserve one’s own forces-a partial and temporary failure to preserve oneself (the sacrifice or payment of the price) is indispensable if the whole is to be preserved for the long run” (Mao 1970, 175).

Sun Tzu problems

Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War” as well as the theorists of network-centric warfare and 4th and 5th generation warfare focus on military success but miss the political dimension with regard to the post-war situation. They underestimate the process of transforming military success into real victory (Macan 2003, Peters 2003, Echevarria 2005). The three core elements of Sun Tzu’s strategy could not be easily applied in our time: Deceiving the opponent in general risks deceiving one’s own population as well, which would be problematic for any democracy. An indirect strategy in general would weaken deterrence against an adversary who can act quickly and decisively. Focusing on influencing the will and mind of the adversary may enable him to avoid a fight and merely resume it at a later time under more favorable conditions.

Sun Tzu is probably more likely to win battles and even campaigns than Clausewitz, but it is difficult to win a war by following his principles. The reason is that Sun Tzu was never interested in shaping the political conditions after the war, because he lived in a time of seemingly never-ending civil wars. The only imperative for him was to survive while paying the lowest possible price and avoiding fighting, because even a successful battle against one enemy could leave you weaker when the moment came to fight the next. As always in history, when people want to emphasize the differences with Clausewitz, the similarities between the two approaches are neglected. For example, the approach in Sun Tzu’s chapter on “Swift Action to Overcome Resistance” would be quite similar to the approach advocated by Clausewitz and practiced by Napoleon. The main problem, however, is that Sun Tzu neglects the strategic perspective of shaping postwar political-social relations and their impact “by calculation” (Clausewitz 1991, 196) on the conduct of the war. As mentioned earlier, this was not a serious issue for Sun Tzu and his contemporaries, but it is one of the most important aspects of warfare in our time (Echevarria 2005¸ Lonsdale 2004).

Finally, one must take into account that Sun Tzu’s strategy is likely to be successful against opponents with a very weak order of forces or associated community, such as warlord systems and dictatorships, which were common opponents in his time. His book is full of cases where relatively simple actions against the order of the opposing army or its community lead to disorder on the part of the opponent until they are disbanded or lose their will to fight altogether. Such an approach can obviously be successful with opponents who have weak armed forces and a weak social base but is likely to prove problematic with more entrenched opponents.

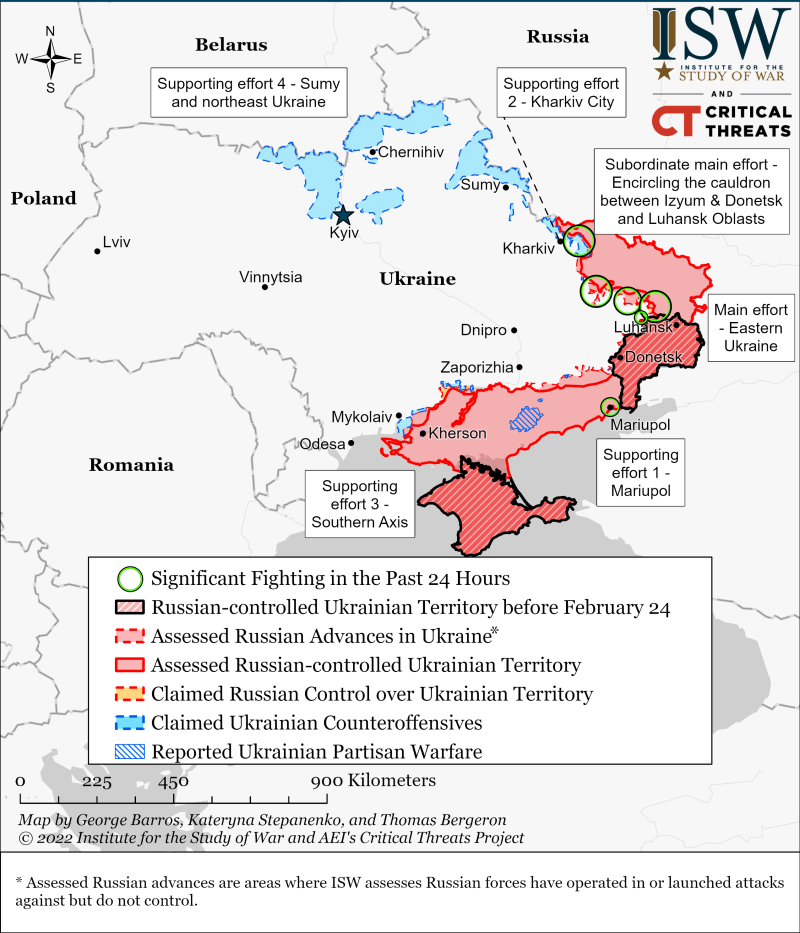

Here, the Ukraine war could be a cautionary example. Apparently, the Russian military leadership and the political circle around Putin were convinced that this war, like the intervention in Crimea, would end quickly, because neither the resistance of the Ukrainian population nor its army was expected, nor the will of the Western states to support Ukraine militarily. To put it pointedly, one could say that in the second Iraq war, Sun Tzu triumphed over Clausewitz, but in the Ukraine war Clausewitz triumphed over Sun Tzu. This also shows that while wars in an era of hybrid globalization (Herberg-Rothe 2020) necessarily also take on a hybrid character, it is much more difficult to successfully practice hybrid warfare-such a conflation of opposites is strategically at odds with those writings of Clausewitz in which he generalizes the principles of Napoleonic warfare, though not with his determination of defense. The Ukraine war can even be seen as evidence of the greater strength of defense as postulated by Clausewitz (Herberg-Rothe 2007).

And Clausewitz?

At first glance, Clausewitz’s position is not compatible with that of Sun Tzu. In his world-famous formula of the continuation of war by other means (Clausewitz 1991, 210), Clausewitz takes a hierarchical position, with politics determining the superior end. Immediately before this formula, however, he writes that politics will pervade the entire warlike act, but only insofar as the nature of the forces exploding within it permits (Clausewitz 1991, ibid.). By this statement, he relativizes the heading of the 24th chapter, which contains the world-famous formula. In addition, all headings of the first chapter, with the exception of the result for the theory, the final conclusion of the first chapter, were written in the handwriting of Marie von Clausewitz, while only the actual text was written by Clausewitz (Herberg-Rothe 2023, on the discovery of the manuscript by Paul Donker).

The tension only implicit in the formula becomes even clearer in the “wondrous trinity,” Clausewitz’s “result for the theory” of war. Here he writes that war is not only a true chameleon, because it changes its nature somewhat in each concrete case, but a wondrous trinity. This is composed of the original violence of war, hatred, and enmity, which can be seen as a blind natural instinct, the game of probabilities and chance, and war as an instrument of politics, whereby war falls prey to mere reason. Violence, hatred, and enmity like a blind natural instinct on the one side, and mere understanding on the other, this is the decisive contrast in Clausewitz’s wondrous trinity. For Clausewitz, all three tendencies of the wondrous trinity are inherent in every war; their different composition is what makes wars different (Clausewitz 1991, 213, Herberg-Rothe 2009).

While Clausewitz formulates a clear hierarchy between the end, aim, and means of war in the initial definition and the world-famous formula, the wondrous trinity is characterized by a principled equivalence of the three tendencies of war’s violence, the inherent struggle and its instrumentality. At its core, Clausewitz’s wondrous trinity is a hybrid determination of war, which is why the term “paradoxical trinity” is more often used in English versions. In his determination of the three interactions to the extreme, made at the beginning of the book, Clausewitz emphasizes the problematic nature of the escalation of violence in the war due to its becoming independent, because the use of force develops its own dynamics (Clausewitz 1991, 192-193, Herberg-Rothe 2007 and 2017). The three interactions have often been misunderstood as mere guides to action, but they are more likely to be considered as escalation dynamics in any war. This is particularly evident in escalation sovereignty in war – the side gains an advantage that can outbid the use of force. However, this outbidding of the adversary (Herberg-Rothe 2001) brings with it the problem of violence taking on a life of its own. This creates a dilemma, which Clausewitz expresses in the wondrous trinity.

This dilemma between the danger of violence becoming independent and its rational application gives rise to the problem formulated at the outset, namely that there cannot be a single strategy applicable to all cases, but that a balance of opposites is required (Herberg-Rothe 2014). In it, the primacy of politics is emphasized, but at the same time, this primacy is constructed as only one of three opposites of equal rank. Thus, Clausewitz’s conception of the wondrous trinity is also to be understood as a paradox, a dilemma, and a hybrid.

As already observed in ethics, there are different ways to deal with such dilemmas (Herberg-Rothe 2011). One is to make a hierarchy between opposites. Here, particular mention should be made of the conception of trinitarian war, which was wrongly attributed to Clausewitz by Harry Summers and Martin van Creveld and was one of the causes of Clausewitz being considered obsolete by Mary Kaldor regarding the “New Wars.” For in the conception of trinitarian war, the balance of three equal tendencies emphasized by Clausewitz is explicitly transformed into a hierarchy of government, army, and people/population. Even if it should be noted that this interpretation was favored by a faulty translation in which Clausewitz’s notion of “mere reason” was transformed into the phrase “belongs to reason alone” (Clausewitz 1984), the problem is systematically conditioned. For one possible way of dealing with action dilemmas is such a hierarchization or what Niklas Luhmann called “functional differentiation”. We find a corresponding functional differentiation in all modern armies – Clausewitz himself had developed such a differentiation in his conception of the “Small War”, which was not understood as an opposition to the “Great War”, but as its supporting element. In contrast, Clausewitz developed the contrast to the “Great War” between states in the “People’s War” (Herberg-Rothe 2007).

A second way of dealing with dilemmas of action is to draw a line up to which one principle applies and above which the other applies – that is, different principles would apply to state warfare than to “people’s war,” guerrilla warfare, the war against terrorists, warlords, wars of intervention in general. This was, for example, the proposal of Martin van Creveld and Robert Kaplan, who argued that in war against non-state groups, the laws of the jungle must apply, not those of “civilized” state war (van Creveld 1998, Kaplan 2002). In contrast, there are also approaches that derive the uniformity of war from the ends, aims, means relation, arguing that every war, whether state war or people’s war, has these three elements and that wars differ only in which ends are to be realized by which opponents with which means (I assume that this is the position of the Clausewitz-orthodoxy). It must be conceded that Clausewitz is probably inferior to Sun Tzu in practical terms with regard to the “art of warfare” – because in parts of his work, he gave the word to a one-sided absolutization of Napoleon’s warfare – while only in the book on defense did he develop a more differentiated strategy (Herberg-Rothe 2007, Herberg-Rothe 2014). Perhaps one could say that Sun Tzu is more relevant to tactics, whereas Clausewitz has the upper hand in strategy (Herberg-Rothe 2014).

Summary

If we return to the beginning, Clausewitz is the (practical) philosopher of war (Herberg-Rothe 2022), while Sun Tzu focuses on the “art of warfare”. As is evident in the hybrid war of the present, due to technological developments and the process I have labeled hybrid globalization (Herberg-Rothe 2020), every war can be characterized as a hybrid. However, as is currently evident in the Ukraine War, the designation of war as a hybrid is different from successful hybrid warfare. This is because hybrid warfare necessarily combines irreconcilable opposites. This mediation of opposites (Herberg-Rothe 2005) requires political prudence as well as the skill of the art of war. The ideal-typical opposition of both is correct in itself, if we provide these opposites with a “more” in each case, not an exclusive “or”.

Clausewitz’s conception is “more” related to

“politics, one’s own material possibilities and those of the opponent, a direct strategy, and that of the late Clausewitz on a relative symmetry of the combatants and the determination of war as an instrument. This can be illustrated with a boxing match in which certain blows are allowed or forbidden (conventions of war), the battlefield and the time of fighting remain delimited (declaration of war, conclusion of peace)”.

Sun Tzu’s conception, on the other hand, refers to more

“directly on the military opponent, his thinking and “nervous system” (Liddel-Heart), an indirect strategy (because a direct strategy in his time would have resulted in a weakening of one’s own position even if successful), and a relative asymmetry of forms of combat”.

Despite this ideal-typical construction, every war is characterized by a combination of these opposites. Consequently, the question is neither about an “either-or” nor a pure “both-and,” but involves the question of which strategy is the appropriate one in a concrete situation. To some extent, we must also distinguish in Clausewitz’s conception of politics between a purely hierarchical understanding and a holistic construction. Put simply, the former conception is addressed in the relationship between political and military leadership; in the latter, any violent action by communities is per se a political one (Echevarria 2005, Herberg-Rothe 2009). From a purely hierarchical perspective, it poses no problem to emphasize the primacy of politics in a de-bounded, globalized world with Clausewitz. If, on the other hand, in a holistic perspective all warlike actions are direct expressions of politics, the insoluble problem arises of how limited warfare could be possible in a de-bounded world.

This raises the question of which of the two, Clausewitz or Sun Tzu, will be referred to more in the strategic debates of the future. In my view, this depends on the role that information technologies, quantum computers, artificial intelligence, drones, and the development of autonomous robotic systems will play in the future – in simple terms, the role that thought and the “soul” will play in comparison to material realities in a globalized world. The Ukraine war arguably shows an overestimation of the influence of thought and soul (identity) on a community like Ukraine, but with respect to autocratic states like Russia and China, possibly an underestimation, at least temporarily, of the possibilities of manipulating the population through the new technologies. Regardless of the outcome of the war, the argument about Clausewitz and/or Sun Tzu will continue as an endless story – but this should not proceed as a mere repetition of dogmatic arguments, but rather answer the question of which of the two is the better approach can be taken in which concrete situation.

Bibliography

Bredow, Wilfried von (2006), Kämpfer und Sozialarbeiter – Soldatische Selbstbilder im Spannungsfeld herkömmlicher und neuer Einsatzmissionen. In: Gareis, S.B., Klein, P. (eds) Handbuch Militär und Sozialwissenschaft. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden.

Clausewitz, Carl von (199119), Vom Kriege. Dümmler: Bonn.

Clausewitz, Carl von (1984), On War. OUP: Oxford.

Creveld, Martin van (1991), The transformation of war. The Free Press: New York.

Echevarria, Antulio II (2005), Fourth-generation warfare and other myths. Carlisle.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2001), Das Rätsel Clausewitz. Fink: München

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2007), Clausewitz’s puzzle. OUP: Oxford

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2009), Clausewitz’s “Wondrous Trinity” as a Coordinate System of War and Violent Conflict. In: International

Journal of Violence and Conflict (IJVC) 3 (2), 2009, pp.62-77.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2011), Ausnahmen bestätigen die Moral. In: Frankfurter Rundschau vom 16. Juni 2011, 31.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2014), Clausewitz’s concept of strategy – Balancing purpose, aims and means. In: Journal of Strategic Studies. 2014; volume 37, 6-7, 2014, pp. 903-925. Also published online (17.4.2014): http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01402390.2013.853175

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2015), Theory and Practice: The inevitable dialectics. Thinking with and beyond Clausewitz’s concept of theory. In: Militaire Spectator. Jaargang 184, Den Haag, Nr. 4, 2015, pp. 160-172.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2020), The dissolution of identities in liquid globalization and the emergence of violent uprisings. In: African Journal of Terrorism and Insurgency Research – Volume 1 Number 1, April 2020, pp. 11-32.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2022), Clausewitz as a practical philosopher. Special issue of the Philosophical Journal of Conflict and Violence. Guest editor: Andreas Herberg-Rothe. Trivent: Budapest, 2022. Also published online: https://trivent-publishing.eu/home/140-philosophical-journal-of-conflict-and-violence-pjcv-clausewitz-as-a-practical-philosopher.html

Kaldor, Mary (2000), Neue und alte Kriege. Organisierte Gewalt im Zeitalter der Globalisierung. Suhrkamp: Frankfurt.

Kaplan, Robert D. (2002), Warrior Politics. Vintage books: New York 2002

Keegan, John (1995), Die Kultur des Krieges. Rowohlt: Berlin

Liddell Hart, Basil Henry (1955), Strategie. Aus dem Englischen übertragen von Horst Jordan, Wiesbaden: Rheinische Verlags-Anstalt.

Lonsdale, David (2004), The nature of war in the information age. Frank Cass: London

Macan Marker, Marwaan (2003), Sun Tzu: The real father of shock and Awe, Asia Times, 2, April 2003

Mao Tsetung (1970), Sechs Militärische Schriften, Peking: Verlag für fremdsprachige Literatur

Mattis, James (2008), quoted in https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/06/08/quote-of-the-day-gen-mattis-reading-list-and-why-he-looks-more-to-the-east/); last access: 15.1.2023.

McNeilly, Mark (2001), Sun Tzu and the Art of Modern Warfare. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Münkler, Herfried (2002), Die neuen Kriege. Rowohlt: Reinbek bei Hamburg.

Peters, Ralph, A New Age of War, New York Post, 10. April 2003.

Summers, Harry G. Jr. (1982), On Strategy: A critical analysis of the Vietnam War. Novato.

Sun Tzu (2008), The Art of War. Spirituality for Conflict. Woodstock.

Sunzi (1988), Die Kunst des Kriegs, hrsg. und mit einem Vorwort von James Clavell, München 1988.

Wassermann, Felix (2015), Asymmetrische Kriege. Eine politiktheoretische Untersuchung zur Kriegführung im 21. Jahrhundert: Campus: Frankfurt.

Featured Image Credits: U.S Army

[powerkit_button size=”lg” style=”info” block=”true” url=”https://admin.thepeninsula.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Clausewitz-and-Sun-Tzu-1.pdf” target=”_blank” nofollow=”false”]

Download

[/powerkit_button]