Abstract

Amidst the continuing conflict in Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin made a notable pronouncement of the end of the US-led unipolar world and the rise of multipolar world order. Against this backdrop of the debate on polarity, my research paper seeks to address the following questions. To what extent have global institutions, mainstream IRT (International Relations Theory) and academia as well as policies reflected if not reinforced Euro-American norms and interests? Does this purported shift to multipolarity require a shift in institutional and theoretical practices reflecting the broad concerns of the Global South? Using global and regional case studies like India (especially in regard to the representation within academia and the glass ceiling affecting institutional practices like Young Professionals Programme), I draw from critical and post-colonial theoretical IR frameworks to argue for a comprehensive reform of the prevalent global institutional and theoretical structures.

Introduction

The Euro-American hegemony runs very deep, pervading a range of institutions, norms, global practices, knowledge and even academic teaching practices.

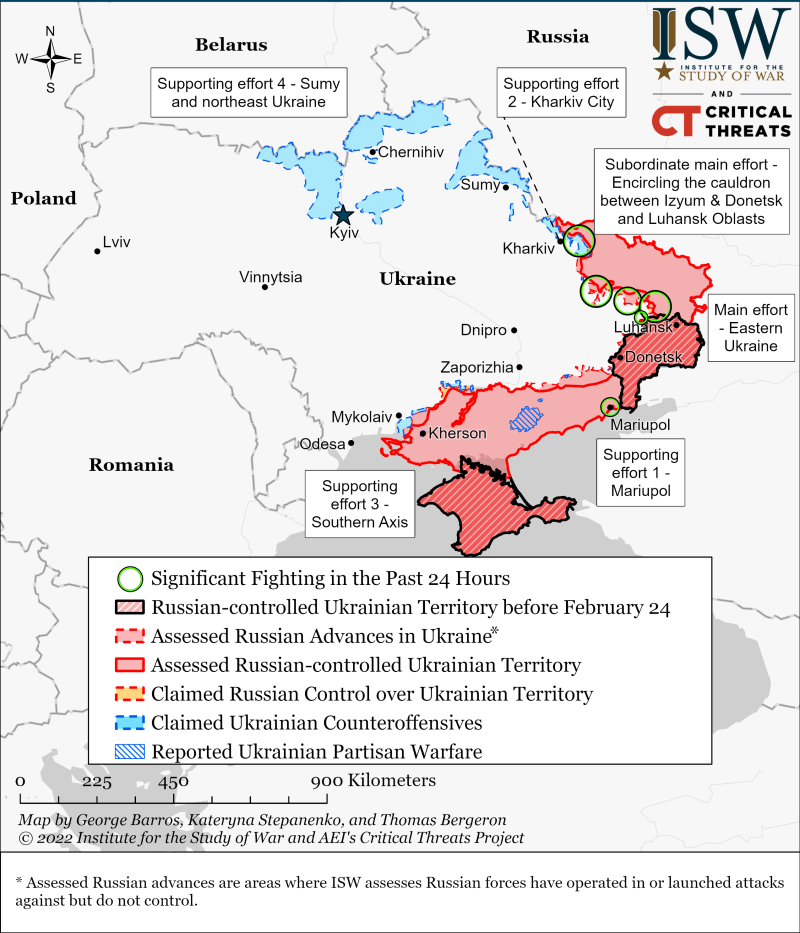

The month of February this year witnessed one of the most defining moments of the post-Cold war era. Marking a major escalation of the simmering conflict that began with the insurgency in Eastern Ukraine in 2014, Russia invaded Ukraine resulting in thousands of casualties and millions of refugees.[1] This conflict inevitably has given rise to a wide range of debates in the global arena, including global governance, institutions, conflict and security. In this regard, one of the most interesting debates that have seen a resurgence is the question of the future of the world order.

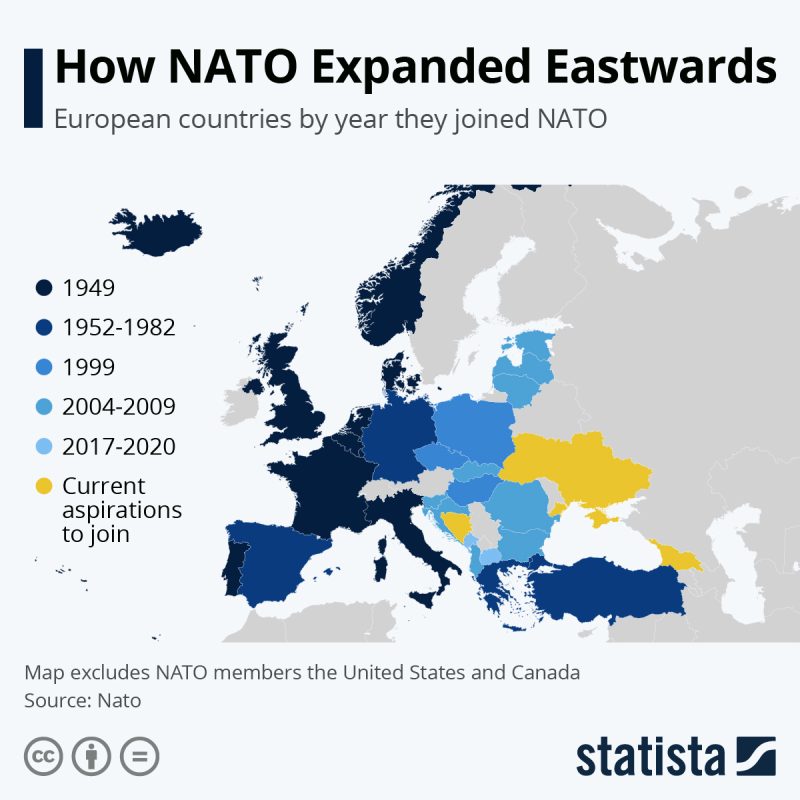

The notion of a shift to multipolar world order has emerged as a prominent theme in the wake of this crisis. This is best exemplified by Vladimir Putin in his address to the St Petersburg International Economic Forum Plenary session, “a multipolar system of international relations is now being formed. It is an irreversible process; it is happening before our eyes and is objective in nature.” It is indeed widely recognised that the brief period of unipolarity, dominated by the US, following the end of the Cold War, has given way to the era of multipolar world order, characterised by ‘new powerful and increasingly assertive centres.’ [2] However, even as this shift to multipolarity seems almost deterministic, there persist legitimate questions on the conduciveness of the current world order to the emergence of these multiple power-centres.

Against this backdrop, my work shall be organised as follows. I commence with a discussion on the shift towards multipolarity, providing the conceptual capital of notions like power and polarity. This shall be followed by my argument that the current global order, exemplified in its norms, institutions, and intellectual resources, fall severely short of the expectations required of the multipolar world order. To illustrate this point, I draw from the case study of India, in particular. I conclude by providing some prescriptions necessary for the transition to multipolarity to be meaningful. Towards this pursuit, I draw from critical post-colonial theoretical frameworks, employing secondary literature review as the overarching method.

Shifts towards multipolarity

Before proceeding to the premise of the shift towards multipolarity, a few conceptual clarifications are in order. Polarity in this context is understood as the modes of distribution of power in the international system. Typically, it is classified as unipolar (e.g. US hegemony in the post-Cold-War era), bipolar (e.g. Russia-US dominance during the Cold War era) and multipolar (e.g. Europe during the pre-World War era). [3] While there are myriad debates on what constitutes power in the global landscape, I draw from the useful typology provided most famously by Joseph Nye – hard, soft, and smart power. Hard power is often described as the typical carrot and stick approach, involving coercion and is often measured in terms of “population size, territory, geography, natural resources, military force, and economic strength.” On the other hand, soft power is described as the ability to influence state preference using intangible attributes like “attractive personality, culture, political values, institutions, and policies” resulting in the perception of legitimacy or moral authority. Smart power is often understood as the instrumental deployment of a combination of both to secure political ends.[4]

The end of the Cold War era, prematurely lauded as the end of history by a scholar, resulted in a brief unipolar moment of US hegemony. As Putin puts it, the US was the predominant power with a limited group of allies which resulted in “all business practices and international relations … interpreted solely in the interests of this power.”[2] However, a range of factors in the twenty-first century led to a crisis in American leadership. The interventionist atrocities carried out in the wake of the September 11 attacks as well as the crisis of global capitalism during the financial crisis of 2008 led to a crisis in American leadership.[5] This period also saw the emergence of new powers like the BRICS nations, who posed a serious challenge to the notion of unipolarity.[3]

As Amitav Acharya and Burry Buzan argue, this diffusion of power has resulted in the ‘rise of the rest’ characterised by the absence of a single superpower. Instead, a number of great and regional powers have emerged with their respective institutions and models of growth. Such a world order is also shaped by a greater role accorded to non-state actors including global organisations, corporations, and social movements as well as non-state actors.[6] Thus, the current global landscape is often termed as multipolar, multi-civilizational and multiplex offering myriad opportunities and benefits for states.[7] The crisis in Ukraine has only bolstered this multipolar moment even further. Consider India as a case in point. The likes of the U.S. (and even China) have competed for India’s affection and India’s seemingly pro-Russia stance has not prevented Delhi’s deeper engagement with her counterparts in the West. These initiatives can only enhance India’s great power status, resulting in potentially a higher degree of multipolarity.[8]

Thus, even as there is an increasing scholarly and policy-based consensus on the shift towards multipolarity, there remain important reservations on whether the current global arena is equipped to deal with the seismic shifts posed by the emergent world order. In other words, does this purported shift to multipolarity require a shift in institutional and theoretical practices reflecting the broad concerns of the Global South? In the next section, I answer in the affirmative, arguing that the dominant norms, institutions, and intellectual resources are broadly skewed towards the preservation of Euro-American hegemony.

The maintenance of Euro-American hegemony: norms, institutions, and academia

The exercise of U.S. hegemonic power involved the projection of a set of norms and their embrace by elites in other nations.

Drawing from Persaud, I argue that dominant powers forge an “academic/foreign policy/security ‘complex’ dedicated to the maintenance of a hegemonic world order.” [9] Such a complex is constituted by an intricate network of norms, institutions and theoretical/ intellectual practices which seek to uphold the status quo. In this section, I examine each of these aspects in detail.

Consider norms, in the first instance. Norms can be defined broadly as the “collective expectations for the proper behaviour of actors.”[10] When certain norms which serve certain interests are considered as general interests, it results in hegemony. The dominant powers socialise and hegemonise other countries into an ideological worldview that best serves their interests. In other words, actors have to orient themselves according to a ‘logic of appropriateness’ framed by these intersubjective notions. In the post World War era, the Roosevelt-led US administration projected a series of norms and principles guided by liberal multilateralism, to shape the post-war international order. Such a form of ‘institutional materiality’ posited a clear separation between the political and the economic realm. The embrace of these norms outside the US occurred through various modes of socialisation including external inducement (e.g. Britain and France), direct intervention and internal reconstruction (e.g. Germany and Japan) as well as military and economic dominance.[11]

The exercise of U.S. hegemonic power involved the projection of a set of norms and their embrace by elites in other nations. Socialisation did occur since U.S. leaders were largely successful in inducing other nations to buy into this normative order. But the processes through which socialisation occurred varied from nation to nation. In Britain and France, shifts in norms were accomplished primarily by external inducement; in Germany and Japan, they resulted from direct intervention and internal reconstruction. In all cases, the spread of norms of liberal multilateralism was heavily tied to U.S. military and economic dominance. [11]

Such norms are often manipulated (and flouted) to their advantage. For example, consider the liberal norm of conditional sovereignty, linked to human rights, spearheaded by the likes of the US and many countries in Western Europe. Assuming the primacy of the individual over the state, it has legitimised intervention on ‘humanitarian’ grounds. However, the execution of these norms has been far more uniform as best exemplified in their differential application in the wake of the atrocities in Kosovo and Rwanda. An intra-state conflict resulting in a humanitarian crisis in Kosovo precipitated a successful multilateral intervention. However, the same decisiveness was starkly absent with regard to a similar (if not greater) conflict in Rwanda which resulted in almost 800,000 casualties and more than two million refugees. Multiple studies have traced the rationale of intervention to the “strategic interests in Europe’s future and the NATO alliance.” Rwanda on the other hand was considered peripheral to the national interests of either Western Europe or the US.[12] This substantiates the argument that the norm of ‘humanitarian intervention’ is often tied more to brutal national interests rather than the protection of human rights.

A range of global norms, ranging from economic norms, dealing with the management of finance, to those dealing with water governance has been shown to be skewed towards the interests of great powers rather than participative in nature.

Consider another instance. The Liberal International Order (LIO) asserts the concept of ‘conditional sovereignty’ where sovereign nation-states are bound to look after their entire populations. A failure to that end invites interference and comments from other nation-states and external agencies. This norm has been pushed forward and spearheaded by first-world countries like the US and Western Europe, much to their advantage. Contrary to this, the neo-Westphalian order is a proponent of the ‘classical sovereignty’ model where nation-states are sovereign within their own territory to administer in any manner they want, obviously with a necessary reverence to human rights, but others are not authorized to interfere in the same. China and other authoritarian regimes have been advocating for the same. So, while the LIO talks about the equality of every individual, the neo-Westphalian order focuses more on the equality of all nation-states.[13] Similarly, a range of global norms, ranging from economic norms, dealing with the management of finance, to those dealing with water governance has been shown to be skewed towards the interests of great powers rather than participative in nature.

Similarly, Cox and Gill have argued how global governance through institutions play a critical role in maintaining hegemony.[14] The multilateral institutions which the US had created both in the political and economic realm have played a critical role in the sustenance of Euro-American (and especially the U.S.) dominance. In other words, even as the international world order shifts to a multipolar one, it has not exactly been accompanied by multilateralism.[15] While multilateralism puts forward the interests of multiple states, most so-called multilateral institutions reflect and reinforce prevailing power configurations.

Consider the United Nations, for instance. It cannot be a mere coincidence that the UN has been ineffectual against most of the contemporary global challenges like climate change, the pandemic etc. when it has not been responsive to the reality of the increasing number of power centres in the multipolar world order.[16] The most glaring evidence is the UNSC. Despite an increasing number of voices on the rise of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the P5 includes only one representative from Asia (which is China) and no members from either Africa or Latin America. In addition, while there has been more than a threefold rise in UN membership, the number of non-permanent seats has only risen from 11 to 15. Even at the administrative levels, the lack of non-western representation is indeed a concern. Besides the absence of a UNSC permanent seat, it is also disheartening to see that it has been years since the Young Professionals Program has been held for the likes of India.

These same institutions are often undermined by the likes of the US, under the facade of NATO. Consider the harrowing intervention in Libya. The NATO intervention on supposedly ‘humanitarian’ grounds in 2011 led to the death of Muamar Gaddafi, violating the legal structures of the UN charter in the process and resulting in a proxy war. The result has been a prolonged state of near-anarchy characterised by arbitrary detentions, executions, mass killings and kidnappings. [17]

The WTO is plagued with similar issues. While it ostensibly reflects the ‘global’ norm of neoliberal free trade, it is “structured and ordered to promote monopolistic competition rather than genuine free trade. These institutional roadblocks include the exclusion of developing countries from several informal decision-making sessions, lack of transparency, coercive decision-making in meetings involving developing countries, astronomical costs involved in Dispute settlement Understanding and so on. The result is that the Western countries have an overwhelming advantage against their counterparts from the Global South. [18]

Lastly, as highlighted earlier, the international policy making apparatus cannot be divorced from the intellectual resources churned by IR academia. Zvobgo, in an insightful piece, has argued how the big three of IR theory – realism, liberalism and constructivism – are built on Eurocentric, raced and racist foundations.[19] The role of imperial policymakers in shaping contemporary IR knowledge has been well acknowledged. Kwaku Danso and Kwesi Aninghave argued about the prevalence of methodological whiteness, which projects White experience as a universal experience.[20] It is no coincidence that the principles of the Westphalian treaty are not significantly different from those underlying the current UN charter. Acharya has argued that racism was integral to the emergence of the US-led world order exemplified in the scant focus on colonialism in UNDHR as well as the “privileging of sovereign equality’ over ‘racial equality.’[21]

These forms of methodological whiteness have had devastating impacts across the world. The projection and the forceful projection of the Weberian state as the fundamental unit of security and conflict management has resulted in disastrous policy-level consequences in Africa which have always been characterised by a range of hybrid political systems beyond the nation-state.[20] Similarly, much of the problematic policies carried out today based on the binaries of ‘developed’ v/s ‘developing’ nations have direct continuities with the legacy of empire and race reflected in dichotomies like ‘civilised v/s uncivilised’.

There also exists historical amnesia of racism in academia, whether in terms of representation or teaching practices. For example, in the US, only 8% of the faculty identify themselves as Black or Latino. Similarly, the configurations of colonialism and racism in building the modern world order are either glossed over or overlooked in most academia.[19] Indian academia is a case in point. As Behera argues, despite the strong tradition of Indian independent IR thought as well as the long history of colonialism, Indian IR has imbibed a definite set of givens including “the infallibility of the Indian state modelled after the Westphalian nation-state as well as a thorough internalization of the philosophy of political realism and positivism.[22] Rohan Mukherjee, for instance, has highlighted an unpublished survey of IR faculty within India wherein the majority self-identified as either liberal or realist.[23]

Thus, the Euro-American hegemony runs very deep, pervading a range of institutions, norms, global practices, knowledge and even academic teaching practices. In the next section, I conclude by outlining certain prescriptions for a future world order which responds to and is far more conducive to the inevitable multipolar shifts.

Conclusion

India has umpteen intellectual resources from Gita and the Sangam literature to stellar modern political philosophers like Gandhi, Tagore and so on, which need to be strategically combined with contemporary IR notions and questions of security, justice and so on.

This paper first established the backdrop of the shift towards multipolarity within the world order by outlining the myriad modes of power through which the ‘Rest’ has caught up with the ‘West.’ In the succeeding section, I demonstrated how a range of norms, institutions and intellectual practices had been historically constructed to maintain Euro-American hegemony as well as promote the interests of the West. In such a world order, certain parochial interests have masqueraded themselves as common or global interests. In the concluding section, I outline certain prescriptions which have become necessary for a more equitable, multi-civilisational world order.

Institutions like the UN require urgent and seismic reforms reflecting the interests of emerging power centres. The number of seats within the Permanent and non-permanent seats must be expanded to include more nation-states from Asia, Africa and Latin America. A revitalisation of the UNGA is highly overdue and requires a focussed and timely debate on the problems of the highest priority at any given time through rationalization of its agenda. [24] Similarly, the proposed WTO reforms, which seeks to move away from multilateralism to impose plurilateralism, should be opposed at all costs. [25]

As Zvobjo puts it eloquently, how IR is taught perpetuates the inequalities which are detailed above. Besides the dominant IR triumvirate, there needs to be an increased focus on critical perspectives as well as increased engagement with the uncomfortable questions of race, empire, colour, and caste.[19] This should be complemented by more diversity in terms of representation within academia. In India specifically, there needs to be increased efforts to construct Indian or South Asian IR notions. India has umpteen intellectual resources from Gita and the Sangam literature to stellar modern political philosophers like Gandhi, Tagore and so on, which need to be strategically combined with contemporary IR notions and questions of security, justice and so on. However, as Mallavarapu reminds us, care needs to be taken to ensure they can address existing inequities in the world order without succumbing or falling prey to jingoism or nativism.[26]

References

[1] Alex Leeds Matthews, Matt Stiles, Tom Nagorski, and Justin Rood, ‘The Ukraine War in data’, Grid, August 4, 2022

[2] Address to participants of 10th St Petersburg International Legal Forum, President of Russia, June 30, 2022

http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/68785

[3]Andrea Edoardo Varisco, ’Towards a Multi-Polar International System: Which Prospects for Global Peace?’, E-International Relations, June 3, 2013.

[4]Aigerim Raimzhanova, ‘Power in IR: hard, soft and smart’, Institute for Cultural Diplomacy and the University of Bucharest, December 2015

[5]Ashraf, N. (2020). Revisiting international relations legacy on hegemony: The decline of American hegemony from comparative perspectives. Review of Economics and Political Science

[6] Kukreja, Veena. “India in the Emergent Multipolar World Order: Dynamics and Strategic Challenges.” India Quarterly 76, no. 1 (2020): 8-23.

[7] Ashok Kumar Beheria, ‘Ask an Expert’, IDSA, April 1, 2020.

https://idsa.in/askanexpert/world-moving-towards-multipolarity-akbehuria

[8]Derek Grossman, ‘Modi’s Multipolar Moment Has Arrived’, RAND blog, June 6, 2022

https://www.rand.org/blog/2022/06/modis-multipolar-moment-has-arrived.html

[9]Persaud, Randolph B. “Ideology, socialization and hegemony in Disciplinary International Relations.” International Affairs 98, no. 1 (2022): 105-123.

[10]Shannon, Vaughn P. “International Norms and Foreign Policy.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics (2017).

[11]Ikenberry, G. John, and Charles A. Kupchan. “Socialization and hegemonic power.” International organization 44, no. 3 (1990): 283-315.

[12] Tracy Kuperus, ‘Kosovo And Rwanda: Selective Interventionism?’, Centre for Public Justice

https://www.cpjustice.org/public/page/content/kosovo_and_rwanda

[13] Falit Sijariya, ‘Democratizing Norms: Jaishankar’s Comments and the Challenge to US Hegemony’, April 22, 2022

[14] Overbeek, Henk. “Global governance, class, hegemony.” Contending Perspectives on Global Governance: Coherence and Contestation 39 (2005).

[15] Tourangbam, Monish. “The UN and the Future of Multilateralism in a Multipolar World.” Indian Foreign Affairs Journal 14, no. 4 (2019): 301-308.

[16] The UN Turns Seventy-Five. Here’s How to Make it Relevant Again, Council on Foreign Relations, Sep 14, 2020.

[17] Ademola Abbas, ‘Assessing NATO’s involvement in Libya’, United Nations University, 27 October 2011

https://unu.edu/publications/articles/assessing-nato-s-involvement-in-libya.html

Lansana Gberi, ‘Forgotten war: a crisis deepens in Libya but where are the cameras?’, Africa Renewal, December 2017 – March 2018

[18] Ed Yates, ‘The WTO Has Failed as a Multilateral Agency in Promoting International Trade’,E-International Relations, April 29, 2014

[19] Kelebogile Zvobgo, ‘Why Race Matters in International Relations’, Foreign Policy, June 19, 2020

https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/19/why-race-matters-international-relations-ir/

[20]Danso, Kwaku, and Kwesi Aning. “African experiences and alternativity in International Relations theorizing about security.” International Affairs 98, no. 1 (2022): 67-83.

[21]Acharya, Amitav. “Can Asia lead? Power ambitions and global governance in the twenty-first century.” International affairs 87, no. 4 (2011): 851-869.

[22]Behera, Navnita Chadha. “Re-imagining IR in India.” In Non-Western international relations theory, pp. 102-126. Routledge, 2009.

[23]Rohan Mukherjee https://mobile.twitter.com/rohan_mukh/with_replies

[24]United Nations Reform: Priority Issues for Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Japan, January 2006

https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/un/reform/priority.html

[25]Abhijit Das, ‘Reform the WTO: do not deform it’, the Hindu Business Line, December 1, 2021

https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/reform-the-wto-do-not-deform-it/article37792701.ece

[26]Shahi, Deepshikha, and Gennaro Ascione. “Rethinking the absence of post-Western International Relations theory in India:‘Advaitic monism’as an alternative epistemological resource.” European Journal of International Relations 22, no. 2 (2016): 313-334.

Feature Image Credits: Foreign Affairs