All foreign policies must aim at attaining purpose, credibility, and efficiency. Purpose defines the main objectives that the country wishes to achieve through its international relations. Credibility comes from international recognition of its actions in this field. And efficiency allows implementation, at the lowest possible cost, of the desired purpose. These three notions, although interwoven and influencing each other, keep their own specificity.

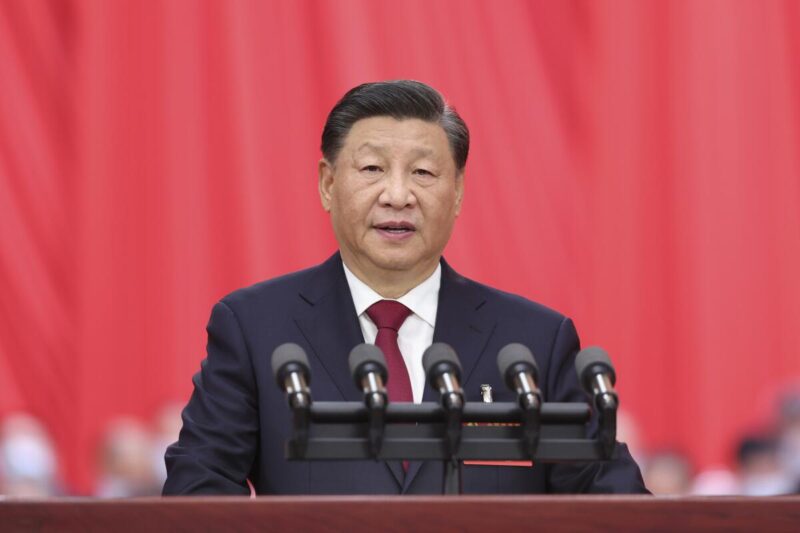

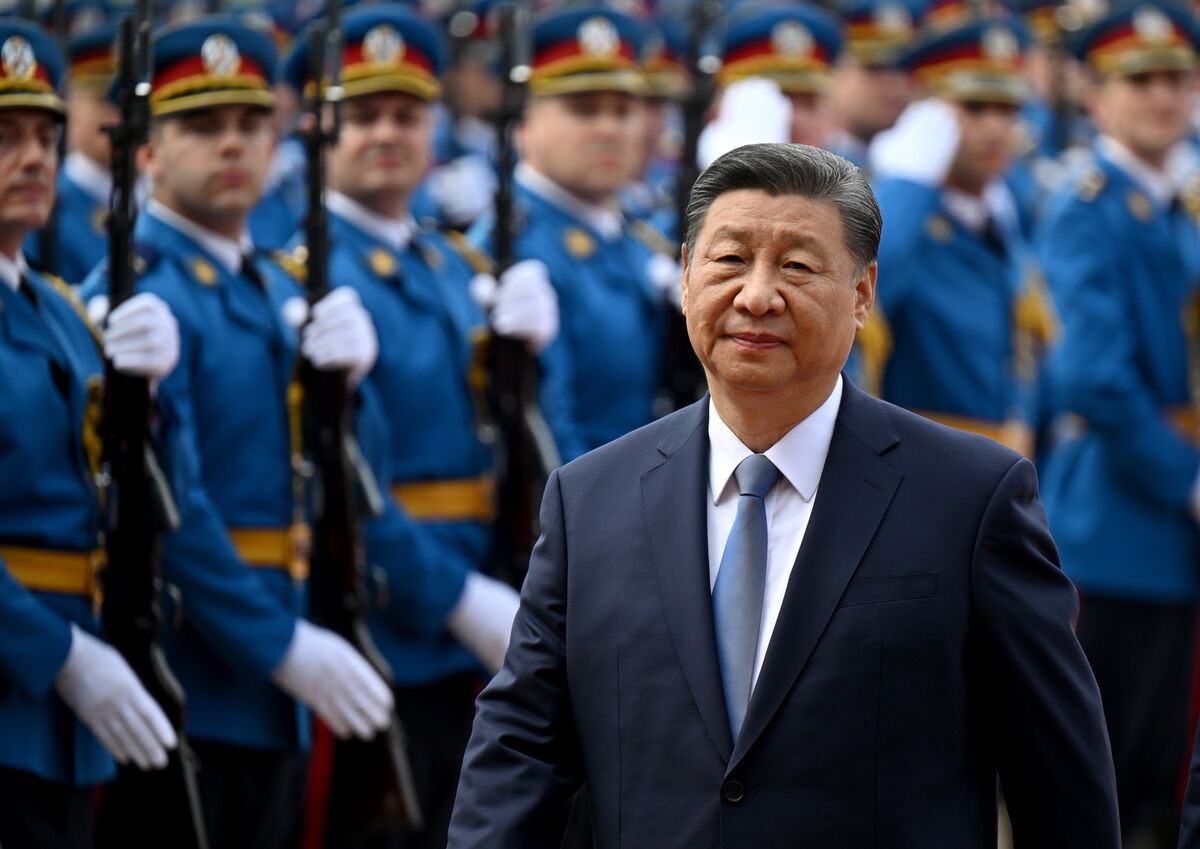

How does Xi Jinping’s foreign policy qualify in these three areas?

Purpose

Its purpose, in tune with that of the Chinese Communist Party before his arrival to power, is sufficiently clear. By 2049, the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic, China should have achieved a prominence commensurate to its glorious past. According to former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, China marches towards the perception of its global destiny with a clear strategy in mind. Such destiny is none other than the resurrection of its historical glory (Rudd, 2017). Projects such as the Chinese Dream of National Rejuvenation, Made in China 2025, and the Belt and Road Initiative, converge in defining concrete goals that lead in that direction. This includes China’s “Great Unification” with Taiwan, the consolidation of a hegemonic position within the South China Sea, making China the epicentre of an Asian-led world economic order, and creating a global infrastructure and transportation network with China at its head. Xi Jinping visualizes the next ten to fifteen years as a window of opportunity to shift China’s correlation of power with the United States. Hence, Beijing seeks the convergence of energies and political determination towards this window of opportunity. The strategic compass of Xi’s foreign policy could not be more precise. Few countries show a clearer sense of its purpose.

Credibility

His foreign policy credibility presents a more mixed result. Vis-à-vis the Western World and several of its neighbours, China’s credibility is at a very low point. However, the situation is different in relation to the Global South, where Xi’s foreign policy promotes four interconnected initiatives to expand China’s influence. Besides the Belt and Road, whose objective is creating a China-led global infrastructure and transportation network, there is also the Global Development Initiative, the Global Security Initiative, and the Global Civilization Initiative. The first, the Global Development Initiative, aims to contrast the unequal distribution of benefits that characterize the West-led development projects with the inclusiveness and balanced nature of this China-led multilateral development project [Hass, 2023]. The other two initiatives, global security and global civilization, present rational and balanced options clearly differentiated from America’s overbearing approach to these areas. In the former case, China’s proposal promotes harmonious solutions to differences among countries through dialogue and consultation [Chaziza, 2023]. The Global Civilization Initiative, on its side, fosters cooperation and interchange between different civilizations, whereby the heterogeneity of cultures and the multiplicity of identities is fully respected [Hoon and Chan, 2023].

The Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka is one of thousands project that China has helped finance in recent years – Image Credit: The Brussels Times (The so-called China’s debt-trap is a narrative trap).

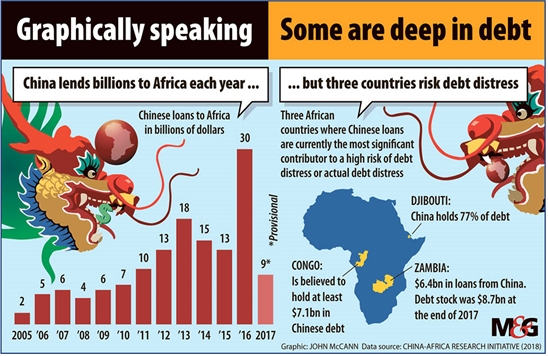

However, three dark areas emerge in Beijing’s credibility with respect to the Global South. Number one is the frustration prevailing in many of these smaller and underdeveloped nations, resulting from the contradiction between China’s openness as a lender and its severity as a creditor. This has given rise to the suspicion of a hidden agenda on its part and has led to the coining of the phrase “debt trap diplomacy”. Number two derives from the arrogance shown by Beijing towards the rights of several of its weakest neighbours, disregarding international law. This seems to delineate a tributary vision of its relations with them. Although this only affects China’s neighbourhood, it projects a haughtiness that contradicts its formulations about a more harmonious, equitable and inclusive world order. Number three is the apparent contradiction between Beijing’s proclamation regarding the value of the heterogeneity of cultures and the diversity of identities and its treatment of non-Han Chinese minorities at home. A feature susceptible to reproducing itself abroad. All the above generates a distance between words and deeds that casts a shadow of doubt concerning China’s sincerity. Hence, even within the Global South, China’s credibility shows a mixed result.

Efficiency

Finally, there is the area of efficiency. It is a very complex one, particularly given China’s over-ambitious purpose. It must be said that until 2008, Beijing succeeded in rising as a significant power without alarming neighbours or the rest of the world. It even attained the geopolitical miracle of doing so without alarming the United States. Indeed, few countries have made such a systematic and conscious effort to project a constructive international image as China has done to this date. This included the notion of “peaceful rise”, which implied a path different from that followed by Germany before World War I and Japan during World War II when they tried to overhaul the international political landscape. China’s path, on the contrary, relied upon reciprocity and the search for mutual benefit with other countries. It was a brilliant soft power marketing strategy that gave China huge goodwill dividends (Cooper Ramo, 2007).

“Observe carefully; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership” – Deng Xioping

Regarding its reunification with Taiwan, it relied on “one country, two systems” and the economic benefits of their interconnection as the obvious means to propitiate their joining together. Regarding its maritime disputes in the South China Sea, after having deferred the resolution of this issue to a more propitious moment, it proposed a Code of Conduct to handle it in the least contentious possible manner. In general, similar approach was evident in Beijing’s handling of various contentious issues. Beijing’s leadership followed Deng Xiaoping’s advice to his successors: “Observe carefully; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership” (Kissinger, 2012, p. 441).

“Like Europe, it has many twenty-first century qualities. Its leaders preach a doctrine of stability and social harmony. Its military talks more about soft than hard power. Its diplomats call for multilateralism rather than unilateralism. And its strategy relies more on trade than war to forge alliances and conquer new parts of the world” – Mark Leonard on China in 2008

Writing in 2008, before the change towards a more assertive foreign policy materialized, Mark Leonard said about China: “Like Europe, it has many twenty-first century qualities. Its leaders preach a doctrine of stability and social harmony. Its military talks more about soft than hard power. Its diplomats call for multilateralism rather than unilateralism. And its strategy relies more on trade than war to forge alliances and conquer new parts of the world” (Leonard, 2008, p. 109). This phrase encapsulates well how China was perceived worldwide, including by the Western World. Not surprisingly, a 2005 world survey on China by the BBC stated that most countries in five continents held a favourable view of that nation. Even more significant was the fact that even China’s neighbours viewed it favourably (Oxford Analytica, 2005). It was a time when all doors opened to China.

2008 represented a turning point. The convergence of several events that year changed China’s perception of its foreign policy role, making it more assertive. Among such events the most significant was the global economic crisis of 2008, the worst crisis since 1929, resulting from America’s financial excesses; other important events were the sweeping efficiency with which China avoided contagion; the fact that China’s economic growth was the fundamental factor in preserving the world from a major economic downturn; and the boost to Chinese self-esteem after the highly successful Beijing Olympic games of that year. In sum, the time in which China had to keep hiding its strengths seemed to have ended.

Although this turning point materialized under Hu Jintao, changes accelerated dramatically after Xi Jinping’s ascend to power. He not only sharpened the edges of the country’s foreign policy but made it more aggressive, even reckless. Xi’s eleven years’ tenure in office has translated into a proliferation of international trouble spots. His overreach and overbearing style misfired, generating a concerted and strong reaction against China. As a result, the costs linked to attaining China’s purpose have skyrocketed. This deserves a more detailed analysis of China’s foreign policy efficiency under Xi.

Intimidatory policies and actions

Xi Jinping’s intimidatory policies and actions on international affairs have been extensive, bringing with them immense resistance.

After dusting off a plan that had remained on paper for years, Xi decided to build seven artificial islands on top of the South China Sea coral reefs. After assuring President Obama they would not be militarized, he proceeded otherwise. Contravening international maritime law, he assigned 12 nautical miles of Territorial Sea and 200 miles of Exclusive Economic Zone to these artificial outposts.

Under the protection of the People’s Liberation Navy, an oil rig was built in the waters claimed by Vietnam as its EEZ. Disrespecting the International Court of Justice’s ruling about the Philippines’ waters in the South China Sea, China has forcefully enforced its exclusionary presence in them. China’s Coast Guard is now authorized to use lethal force against foreign vessels operating within maritime areas under its jurisdiction claims. This, notwithstanding that China’s claimed jurisdiction, goes far beyond what is recognized by the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea or the International Court of Justice while disputed by several other countries.

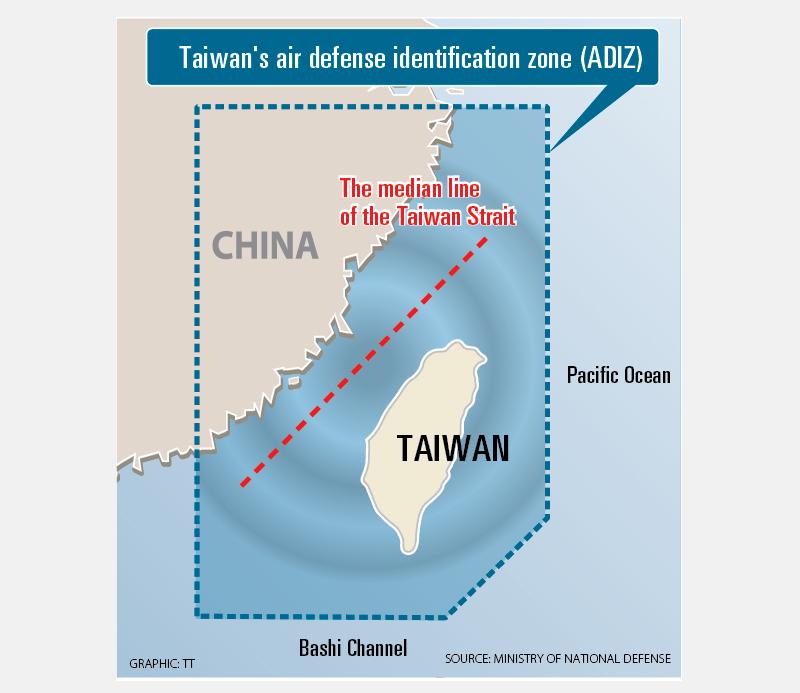

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) began to ignore the median line in the Taiwan Strait, which it had respected for decades. Frequent and increasingly bold incursions within Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone and reiterated calls to the PLA to prepare for war in Taiwan have become the new normal. The Senkaku-Diaoyu islands, disputed with Japan, have been declared one of China’s core interests, thus closing the door to a negotiated solution. This has translated into the systematic incursion of Chinese maritime law enforcement ships and planes into the territorial and contiguous maritime space of these islands, currently occupied by Japan. Beijing unilaterally imposed an Air Defence Identification Zone over two-thirds of the East China Sea, forcing foreign aircraft to identify themselves under threat of “defensive measures” by the PLA Air Force.

Since 2017, China has reneged on the quite borders with India and engaged in a series of border skirmishes. It has resorted to intrusions into border regions under dispute resulting in a major skirmish in Ladakh with significant casualties, the first since 1987. In 2023, China released an official standard map showing India’s state of Arunachal Pradesh in Northeast India and Askai Chin plateau in the Indian territory of Ladakh in the west, as official parts of its territory, despite India’s objections. At the same time, it renamed 11 places in Arunachal Pradesh with Chinese names. When South Korea decided to deploy the US Army’s THAAD (Terminal High-Altitude Area Defence) ballistic missile defence, as protection against the growing North Korean threat, China put in motion an economic boycott of South Korean products and services. When Australia and New Zealand protested against Chinese interference in their domestic political systems, Beijing openly threatened to impose economic sanctions on governments or private actors criticising China’s behaviour. A few years later, it effectively banned most Australian exports when Canberra proposed an international scientific investigation on the origins of COVID-19. When Canada detained Huawei’s heiress, Meng Wanzhou, answering an American judicial request, Beijing jailed and presented accusations against two Canadian businessmen based in China (releasing them hours after Meng was released).

Antagonizing Americans and Europeans

Xi’s rhetoric in relation to the U.S. has been highly aggressive. Reversing the terms of Deng Xiaoping’s advice to his successors to hide China’s strengths while bidding for right time, Xi has alerted America about its intent to challenge and displace it as the foremost power soon. He has repeatedly referred; to the primacy of China in the emerging world order as its most important objective, to the next ten to fifteen years as the inflexion point when a change in the correlation of power between the two countries should be taking place, to the need to overcome the U.S.’ technological leadership, to the necessity for the PLA to ready itself to wage and win wars, and to the next ten years as a time of confrontation and dangerous storms.

Xi Jinping starts his European tour in Paris on May6, 2024, his first in five years as China-EU trade relation have hit a low. Picture Source: Sky News.

China’s actions have also antagonized the Europeans. These relate to China’s refusal to use the term “invasion” when referring to Russia’s actions in Ukraine; supporting the arguments provided by Russia concerning the causes of the war; placing the responsibility of the conflict on the US and the NATO; abstaining from voting in the U.N. on the West’s resolutions against Russia; demonstrating its strong strategic relations with Russia that is described as “partnership without limits”; the conduct of military exercises with Russia while war rages on in Ukraine; and providing indirect support for Russia’s war effort through surveillance drones, computer chips, and other critical components for its defence industry. Though all of the above are sovereign decisions of China, Europe, as China’s major trading partner, expects some support to their position and a neutral approach to the conflict from China.

For the most part, Beijing’s above foreign policy actions were duly accompanied by a bellicose so-called “wolf warrior diplomacy”. It aggressively reacted to perceived criticism of the Chinese government.

Domestic actions impacting its Image Abroad

However, with its aggressive display in the international arena, some domestic actions have negatively permeated abroad. Brushing aside Deng Xiaoping’s commitment to respect Hong Kong’s autonomy for a period of fifty years, Xi reclaimed complete jurisdiction over such territory since his arrival to power. Within a process of actions and reactions, accelerated by the progressive strangulation of Hong Kong’s liberties, Beijing finally imposed a National Security Law over the territory. This ended the Hong Kong Basic Law, which guaranteed its autonomy. By burying the principle of “one country, two systems” established by Deng, Beijing was, at the same time, closing out any possibility of Taiwan’s willing accession to the People’s Republic. Henceforward, only force may accomplish that result.

On the other hand, the brutal Sinicization of Xinjiang Province has shaken the liberal conscience of Western countries, with particular reference to Europe. The Uyghur population re-education camps have been compared to the Soviet’s Gulag. Beijing’s combative reaction to any foreign criticism in this regard, has compounded China’s image crisis in Europe.

Any remaining trace of the so-called peaceful emergence of China has completely disappeared under Xi Jinping. Under his rudder, China has brought to the limelight a revisionist and tributary vision of the international order. Not surprisingly, interwoven policies and decisions emanating from different geographical points have been converging to contain China. In an unnecessary way, Beijing under Xi has been instrumental in multiplying the barriers to realising its purpose.

Keeping China at bay

The number of initiatives to keep China at bay has multiplied. Its list includes the following. The U.S., Japan, Australia and India created a strategic quadrilateral forum known as the Quad, which is none other than a factual alliance aimed at the containment of China. More formally, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States gave birth to a strategic military alliance with the same goal. On its side, Japan and Australia signed a security cooperation agreement.

Leaving aside its restrained post-war defence policy, Japan doubled its defence budget to 2 per cent of its GDP. This will transform Japan to number three position worldwide regarding military expenditure, just behind the U.S. and China. Within the same context, Japan and the U.S. established a joint command of its military forces while agreeing to create a shared littoral force equipped with the most modern anti-ship missiles. Meanwhile, Japan is set to arm itself with state-of-the-art missiles. Overcoming their longstanding mutual mistrust, Japan and South Korea, jointly with the U.S., established a trilateral framework to promote a rules-based Indo-Pacific region. On the same token, Japan, the Philippines, and the U.S. held a first-ever trilateral summit aimed at defence cooperation and economic partnership. They pledged to protect freedom of navigation and overflight in the South China and East China Seas. Several joint naval exercises have taken place in the South China Sea to defend the principle of freedom of navigation, with France participating in the latest one.

After several fruitless years of attempting to mollify China’s position concerning their maritime dispute in the South China Sea, the Philippines decided to renew its Mutual Defence Treaty with the U.S., which had elapsed in 2016. Meanwhile, most Southeast and East Asian countries on China’s periphery are rapidly increasing their military spending while still continuing to support the U.S. security umbrella. Although pledging to remain neutral, even Vietnam, a traditional de facto ally of China, decided to upgrade its diplomatic relations with Washington to the highest level.

America’s several decades policy of “strategic ambiguity” in relation to Taiwan evaporates as a result of China’s increasing threats and harassment to the island. On top of unambiguous support to Taipei by the President and the Congress, the Pentagon has formulated a military doctrine for Taiwan’s defence in case of invasion. The idea of defending Taiwan if invaded is also taking shape in Japan.

The European Union adhered to the U.S., the United Kingdom and Canada in sanctioning the Chinese authorities involved in human rights abuses in Xinjiang (the first such European sanction since Tiananmen in 1989). Equally, and for the same reasons, the European Parliament refused to ratify the long-time negotiated investment agreement between China and the European Union. China’s aggressive reaction to such a decision only toughened the European position further. Significantly, European contacts with Taiwan have increased as its democratic nature, and China’s harassment of it are providing a new light on the subject. In that context, the European Parliament officially received Taiwan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs.

A gigantic containment Bloc

France and Germany sent warships to navigate the South China Sea in defiance of Beijing’s claimed ownership of 90 per cent of the Sea. NATO’s updated “Strategic Concept” document, which outlines primary threats to the alliance, identified China for the first time as a direct threat to its security: “The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests, security and values (…) It strives to subvert the rules-based international order, including in the Space, Cyber and Maritime domains (…)The deepening strategic partnership between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation and their mutually reinforcing attempts to undercut the rules-based international order run counter to our values and interests” (NATO, 2022). Not surprisingly, NATO’s last summit included the heads of state and governments of Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea.

As a result of Xi Jinping’s actions and policies, China is now being subjected to a gigantic geostrategic containment force—a true block integrated by nations and organizations from four continents. For a country like China, which traditionally identified with political subtlety and enjoyed universal goodwill until not so long ago, this change in its strategic environment is not a small development. Xi’s calculations that acting boldly had become possible as China was powerful enough, its economy big enough, its neighbours dependent on it, and the U.S. resolve as uncertain have proved wrong and grossly misfired. At this point, China’s conundrum might leave China with few options short of war. According to former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, the 2020s have become the “decade of living dangerously”, as, within it, a war between China and the U.S. will most probably erupt (Rudd, 2022, chapter 16).

In sum

An evaluation of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy, using the notions of purpose, credibility, and efficiency as bases, would present the following result. Its purpose is crystal clear, which translates into a high mark. Credibility, on its part, shows mixed results: Not entirely unsatisfactory nor satisfactory. In terms of efficiency, though, Xi Jinping has openly failed. The lack of efficiency associated with his outreach adversely affects the attainment of China’s foreign policy purpose, creating countless barriers to its fulfilment. This lack of efficiency affects the country’s credibility as well. The downturn has been dramatic when comparing the current situation of China’s foreign policy to the one that prevailed before 2008 and, more precisely, to Xi Jinping’s ascension to power.

References:

Chaziza, M. (2023) “The Global Security Initiative: China’s New Security Architecture for the Gulf”, The Diplomat, May 5.

Cooper Ramo, J. (2007). Brand China. London: The Foreign Policy Centre.

Hass, R. (2023) “China’s Response to American-led ‘Containment and Suppression’”, China Leadership Monitor, Fall, Issue 77.

Hoon, C.Y. and Chan, Y.K., (2023) “Reflections on China’s Latest Civilisation Agenda”, Fulcrum, 4 September.

Kissinger, H. (2012). On China. New York: Penguin Books.

Leonard, M. (2008). What Does China Think? New York: Public Affairs.

NATO (2022). “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept”, June 29.

Oxford Analytica (2005). “Survey on China”, September 20th.

Rudd, K. (2022). The Avoidable War. New York: Public Affairs.

Rudd, K. (2017). “Xi Jinping offers a long-term view of China’s ambitions”, Financial Times, October 23.

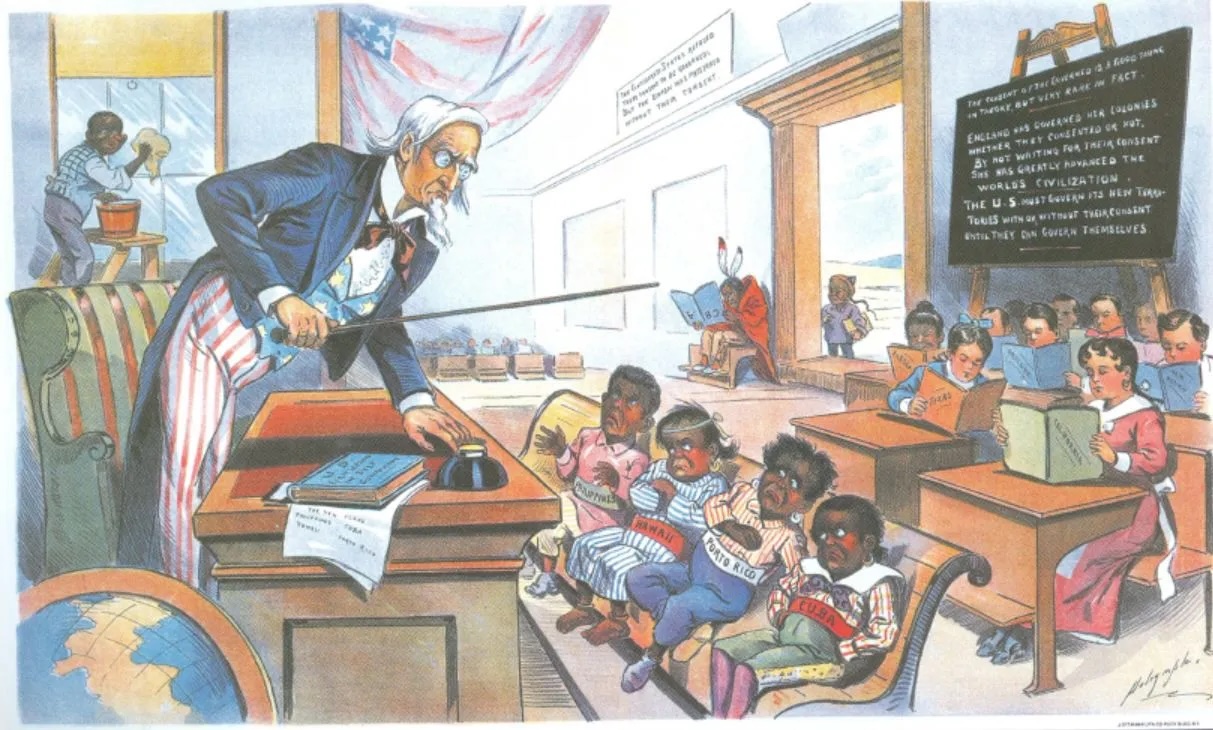

The Philippines, a twice-colonized archipelago that achieved its complete independence in 1946, is a member of the ASEAN and an essential player in the geopolitics of the Southeast Asia region. Its status is owed mainly to its rapidly growing economy, of which the services industry is the most significant contributor, comprising 61% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bajpai, 2022). Services refer to various products – for example, business outsourcing, tourism, and the export of skilled workers, healthcare workers, and labourers in other industries. In recent years, a growing demand for qualified professionals has grown as the economy has grown, thus necessitating more robust educational systems (Bajpai, 2022). Although the Philippines has a high literacy rate, hovering at around 97%, the efficacy of its educational system is often called into question (“Literacy Rate and Educational Attainment”, 2020). Administration oversight, infrastructural deficiencies, and pervasive corruption in the government that seeps into the entities responsible for educational reform are significant issues that legitimize these doubts (Palatino, 2023). However, reforming the current flaws in the system requires an understanding of the basic underlying structure of the country’s educational system as it is today. This fundamental understanding can help clarify specific political trends in the status quo and highlight the importance of proper historical education in developing a nation. Despite its ubiquity in nearly every curriculum, the study of history as a crucial part of the education system is often not prioritized, leading to an underdeveloped understanding of the society’s culture and previous struggles with colonial exploitation. Though it is present in the Philippines’ education today, it continues to change because of its historically dynamic demographic and political atmosphere.

The Philippines, a twice-colonized archipelago that achieved its complete independence in 1946, is a member of the ASEAN and an essential player in the geopolitics of the Southeast Asia region. Its status is owed mainly to its rapidly growing economy, of which the services industry is the most significant contributor, comprising 61% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bajpai, 2022). Services refer to various products – for example, business outsourcing, tourism, and the export of skilled workers, healthcare workers, and labourers in other industries. In recent years, a growing demand for qualified professionals has grown as the economy has grown, thus necessitating more robust educational systems (Bajpai, 2022). Although the Philippines has a high literacy rate, hovering at around 97%, the efficacy of its educational system is often called into question (“Literacy Rate and Educational Attainment”, 2020). Administration oversight, infrastructural deficiencies, and pervasive corruption in the government that seeps into the entities responsible for educational reform are significant issues that legitimize these doubts (Palatino, 2023). However, reforming the current flaws in the system requires an understanding of the basic underlying structure of the country’s educational system as it is today. This fundamental understanding can help clarify specific political trends in the status quo and highlight the importance of proper historical education in developing a nation. Despite its ubiquity in nearly every curriculum, the study of history as a crucial part of the education system is often not prioritized, leading to an underdeveloped understanding of the society’s culture and previous struggles with colonial exploitation. Though it is present in the Philippines’ education today, it continues to change because of its historically dynamic demographic and political atmosphere.

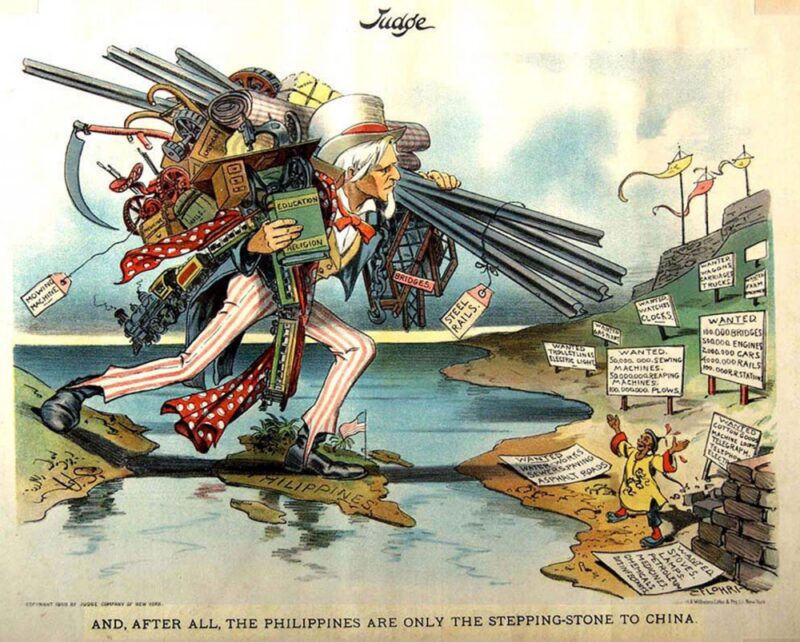

Uncle Sam, loaded with implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to get across the Pacific to China (represented by a small man with open arms), who excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. With the expansionist policy gaining greater traction, the possibility for more imperialistic missions (including to conflict-ridden China) seemed strong. The cartoon might be arguing that such endeavours are worthwhile, bringing education, technological, and other civilizing tools to a desperate people. On the other hand, it could be read as sarcastically commenting on America’s new propensity to “step” on others. “AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA,” in Judge Magazine, 1900 or 1902.

Uncle Sam, loaded with implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to get across the Pacific to China (represented by a small man with open arms), who excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. With the expansionist policy gaining greater traction, the possibility for more imperialistic missions (including to conflict-ridden China) seemed strong. The cartoon might be arguing that such endeavours are worthwhile, bringing education, technological, and other civilizing tools to a desperate people. On the other hand, it could be read as sarcastically commenting on America’s new propensity to “step” on others. “AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA,” in Judge Magazine, 1900 or 1902.