Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James A Robinson have been awarded the Nobel (really the Riksbank prize) in economics “for studies of how institutions are formed and affect prosperity.” Daron Acemoglu is a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Simon Johnson is a professor at the same university. And James Robinson is a professor at the University of Chicago.

Here is what the Nobel judges say was the reason for winning:

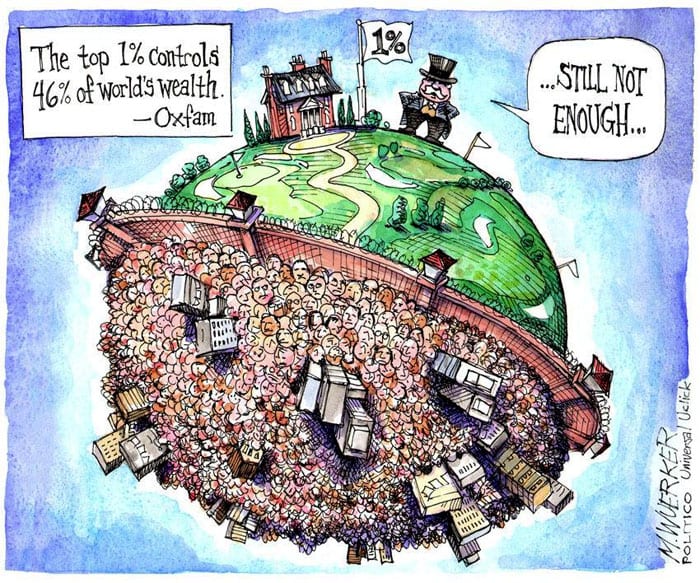

Today, the richest 20 percent of countries are around 30 times wealthier than the poorest 20 percent of countries. The income gaps across countries have been highly persistent over the past 75 years.39 The available data also show that between-country disparities in income have grown over the past 200 years. Why are the income differences across countries so large and so persistent?

This year’s Laureates have pioneered a new approach to providing credible, quantitative answers to this crucial question for humanity. By empirically examining the impact and persistence of colonial strategies on subsequent economic development, they have identified historical roots for the extractive institutional environments that characterize many low-income countries. Their emphasis on using natural experiments and historical data has initiated a new research tradition that continues to help uncover the historical drivers of prosperity, or lack thereof.

Their research centers on the idea that political institutions fundamentally shape the wealth of nations. But what shapes these institutions? By integrating existing political science theories on democratic reform into a game-theoretic framework, Acemoglu and Robinson developed a dynamic model in which the ruling elite make strategic decisions about political institutions—particularly whether to extend the electoral franchise—in response to periodic threats. This framework is now standard for analyzing political institutional reform and has significantly impacted the research literature. And evidence is mounting in support of one of the model’s core implications: more inclusive governments promote economic development.

Over the years (or is it decades?) I have posted on the work of various Nobel winners in economics.

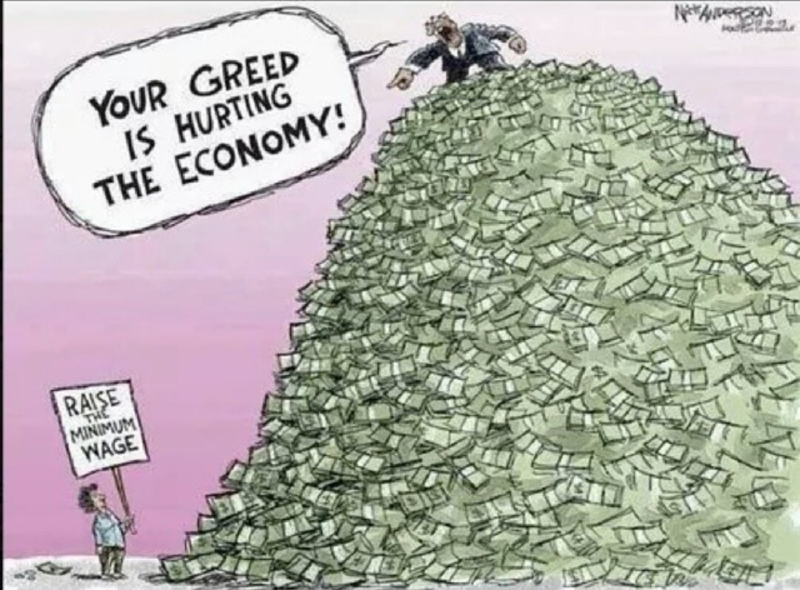

What I have found is that, whatever the quality of the winner’s work, he or she (occasionally) usually got the prize for their worst piece of research, namely work that confirmed the mainstream view of the economic world, while not actually taking us further into understanding its contradictions.

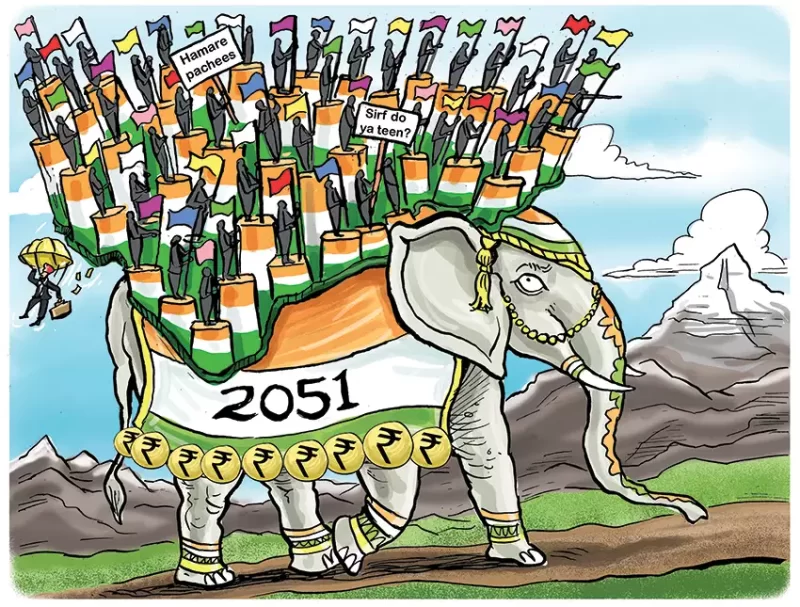

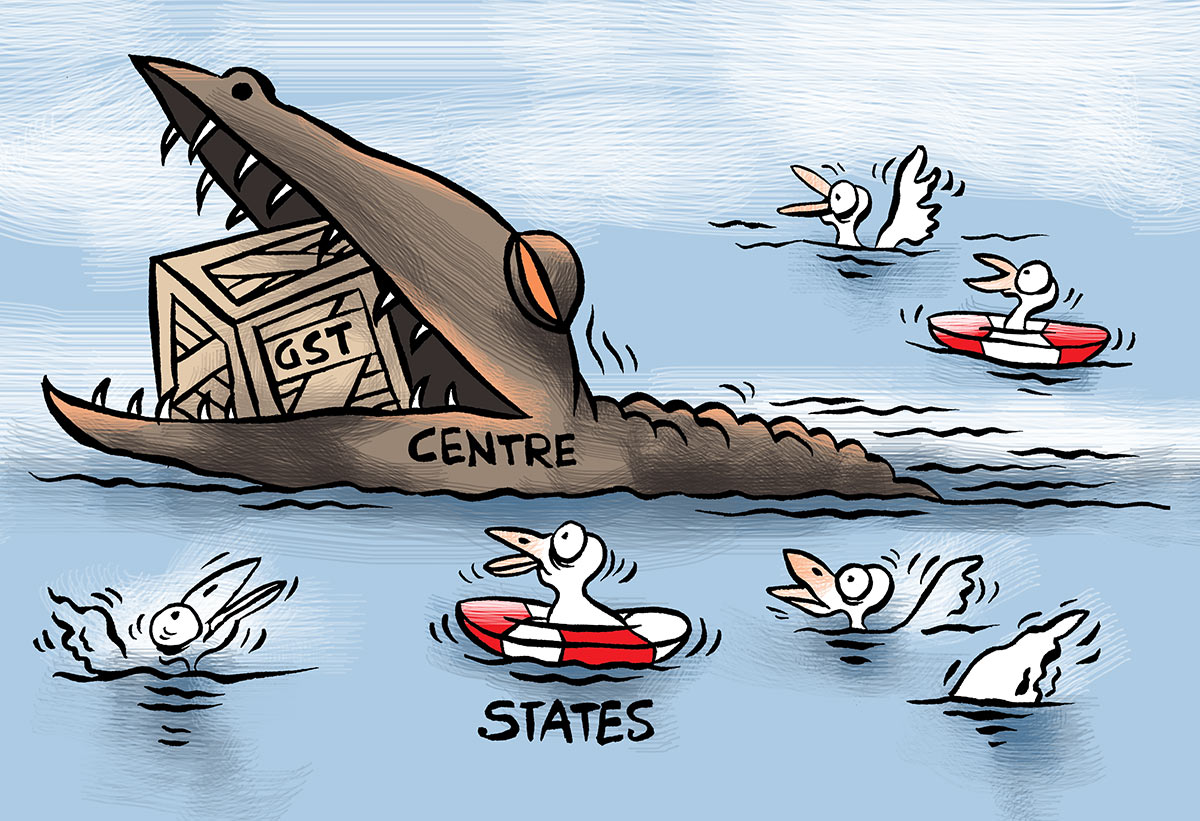

This conclusion I think applies to the latest winners. The work for which they received the $1m prize is for research that purports to show that those countries that achieve prosperity and end poverty are those that adopt ‘democracy’ (and by that is meant Western-style liberal democracy where people can speak out (mostly), can vote for officials every so often and expect the law to protect their lives and property (hopefully). Societies that are controlled by elites without any democratic accountability are ‘extractive’ of resources, do not respect property and value and so over time do not prosper. In a series of papers applying some empirical analysis (ie correlating democracy (as defined) with levels of prosperity), the Nobel winners claim to show this.

Indeed, the Nobel winners argue that colonisation of the Global South in the 18th and 19thcenturies could be ‘inclusive’ and so turn the likes of North America into prosperous nations (forgetting the indigenous population) or ‘extractive’ and so keep countries in dire poverty (Africa). It all depends. Such is the theory.

This sort of economics is what is called institutional, namely that it is not so much the blind forces of the market and capital accumulation that drives growth (and inequalities), but the decisions and structures set up by humans. Supporting this model, the winners assert that revolutions precede economic changes and not that economic changes (or the lack thereof before a new economic environment) precede revolutions.

Two points follow from this. First, if growth and prosperity go hand in hand with ‘democracy’ and the likes of the Soviet Union, China, and Vietnam are considered to have elites that are ‘extractive’ or undemocratic, how do our Nobellists explain their undoubted economic performance? Apparently, it is explained by the fact they started out poor and had a lot of ‘catching up’ to do, but soon their extractive character will catch up with them and China’s hyper-growth will run out of steam. Perhaps now?

Second, is it correct to say that revolutions or political reforms are necessary to set things on the path to prosperity? Well, there may be some truth in that: would Russia in the early 20thcentury be where it is today without the 1917 revolution or China be where it is in 2024 without the revolution of 1949? But our Nobellists do not present us with those examples: theirs are getting the vote in Britain in the 19th century or independence for the American colonies in the 1770s.

But surely, the state of the economy, the way it functions, the investment and productivity of the workforce also have an effect? The emergence of capitalism and the industrial revolution in Britain preceded the move to universal suffrage. The English Civil War of the 1640s laid the political basis for the hegemony of the capitalist class in Britain, but it was the expansion of trade (including in slaves) and colonisation in the following century that took the economy forward.

The irony of this award is that the best work of Acemoglu and Johnson has come much more recently than in the past works that the Nobel judges have focused on. Only last year, the authors published Power and Progress , where they pose the contradiction in modern economies between technology driving up the productivity of labour but also with the likelihood of increased inequality and poverty. Of course, their policy solutions do not touch on the question of a change in property relations, except to call for a greater balance between capital and labour.

What you can say in favour of this year’s winners is that at least their research is about trying to understand the world and its development, instead of some arcane theorem of equilibrium in markets that many past winners have been honoured for. It’s just that their theory of ‘catching up’ is vague (or ‘contingent’ as they put it) and unconvincing.

I think we have a much better and more convincing explanation of the processes of catching up (or not) from the recent book by Brazilian Marxist economists Adalmir Antonio Marquetti, Alessandro Miebach and Henrique Morrone who have produced an important and insightful book on global capitalist development, with an innovative new way of measuring the progress for the majority of humanity in the so-called Global South in ‘catching up’ on living standards with the ‘Global North’. This book deals with all the things that the Nobel winners ignore: productivity, capital accumulation, unequal exchange, exploitation—as well as the key institutional factor of who controls the surplus.